Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones

versión On-line ISSN 2174-0534versión impresa ISSN 1576-5962

Rev. psicol. trab. organ. vol.30 no.3 Madrid dic. 2014

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rpto.2014.11.006

How negotiators are transformed into mediators. Labor conflict mediation in Andalusia

Cómo se transforma a los negociadores en mediadores. La mediación en los conflictos laborales en Andalucía

Francisco J. Medinaa, Virginia Vilchesa, Marina Oterob and Lourdes Munduatea

aUniversity of Seville, Spain

bAGORA, Spain

Financial Support: Grant from project PSI2008-005 (Spanish government [Gobierno de España]).

ABSTRACT

In this paper we describe and analyze the Extrajudicial System for Labor Conflict Resolution in Andalusia. We begin by emphasizing the major relevance of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) in a European context and the need to benefit from different ADR experiences. Next, we comment on the situation in Spain and focus on the Andalusia's system. This system was created by an interprofessional agreement between the most representative employers' union and the two largest trade unions with the support of the national government. During the first fourteen years more than 4,500 conflicts have been submitted affecting more than 400,000 companies and 3,000,000 employees. Collective mediations are conducted by a team of four mediators, two of them appointed by the principal employers association, and the two other by the two largest trade unions.

Key words: Labor Mediation. Collective mediation. Dispute resolution. Right conflicts. Conflicts of interest.

RESUMEN

En este trabajo analizamos el Sistema Extrajudicial de Conflictos Laborales de Andalucía. Comenzamos por enfatizar la relevancia de los mecanismos extrajudiciales de resolución de conflictos en Europa y la necesidad de beneficiarnos de las diferentes experiencias. A continuación comentamos la situación en España, focalizando en el caso del sistema andaluz. Este sistema fue creado por un acuerdo entre los sindicatos más representativos y la patronal con el apoyo del gobierno autonómico. Durante los 14 años de vigencia del sistema se han tratado más de 4.500 conflictos, que afectaban a más de 400.000 organizaciones y a tres millones de empleados. El sistema de mediación está formado por un equipo de cuatro mediadores, dos pertenecientes a las principales centrales sindicales y dos a la confederación de empresarios.

Palabras clave: Mediación laboral. Mediación colectiva. Resolución de disputas. Conflictos de derechos. Conflicto de intereses.

Nowadays there is a general dissatisfaction with the Administration of Justice (Verdonschot, Barendrecht, & Kamminga, 2008). In the United States, this dissatisfaction was obvious during the Pounds Conference, where prestigious jurists and lawyers expressed their worries about the increase in the costs, delays, and workload of the Administration of Justice. In Europe, the necessity for improving the access to justice encouraged the Council of Europe to create the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) with the objective (among others) of promoting the effective implementation of the Council of Europe's instruments for the judicial organization (CEPEJ, 2010). In Spain, the III Barometer of the Observatory of the Judicial Activity exposed the discredit of the Spanish Administration of Justice because 65% of the interviewed considered that the Spanish Administration of Justice works "bad or very bad" (Fundación Wolters Kluwer, 2012).

This general dissatisfaction is caused by a "gap in the access to justice". This gap is understood as the difference between the type of protection that individuals need from the legal system and what those systems are able to offer (Barendrecht et al., 2008). Mediation has been one of the tools proposed in order to lessen this gap. In this sense, it is worth mentioning that the concept of access to justice has recently evolved. Traditionally, international instruments for the protection of human rights have codified the concept of access to justice as the "right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted by the constitution or by law"(Article 8 of the UDHR), "the right to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal established by law" (Article 14 of the ICCPR), or "the right to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law" (Article 6 of the ECHR). Today, the right to access to justice goes beyond this definition and it is understood as the right to access to adequate dispute resolution mechanisms and not only the right to access to courts (EC, 2004). Following this approach, Carretero (2011) claims that we should look for different models for dispute resolution in Europe with the objective of offering more and better responses to people's legal needs, and using one or another mechanism should depend on the nature of the problem. Therefore, mediation has an important role to perform in the new concept of access to justice and the state has an important role to safeguard the right of access to justice.

Mediation is understood as one one of the most constructive methods for conflict resolution (Brett, Goldberg, & Ury, 1990). Developing an in-depth knowledge of how different mediation systems are functioning is essential to benefit from them and to suggest relevant research questions for the mediation practice. We will present a paper with the following structure: we begin by emphasizing the increasing relevance of mediation in Europe and next we describe the Extrajudicial System for Labor Conflict Resolution in Andalusia (Spain).

Mediation in Europe

Mediation is an assisted negotiation by a third neutral, the mediator, who differently from judges and arbitrators has no power to impose a solution for the parties (Goldberg et al., 1999). We follow the concept of mediation stated in the Directive 2008/52/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters (EU Directive on Mediation) which establishes that "mediation means a structured process, however named or referred to, whereby two or more parties to a dispute attempt by themselves, on a voluntary basis, to reach an agreement on the settlement of their dispute with the assistance of a mediator. This process may be initiated by the parties or suggested or ordered by a court or prescribed by the law of a member state" (Dir. 2008/52/EC,3).

In Europe, the mediation is developing at a lower pace than in other countries such as United States, Australia or Argentina; however, the value of mediation has been recognized by the most important international organizations in Europe. For instance, the Council of Europe has elaborated different recommendations in this matter such as Recommendation (98) 1 on Family Mediation, Recommendation (2002) 10 on Civil Mediation, Recommendation (99) concerning mediation in penal matters, Recommendation (2001) 9 on alternatives to litigation between administrative authorities and private parties, and Recommendation (2002) 10 on mediation in civil matters. The European Union published in 2002 the Green Book on Alternative Dispute Resolution in Civil and Commercial Law in which it highlights the potential of mediation as an alternative dispute resolution. And, in 2008 the European Directive on Mediation (European Union, 2008) was approved with the objective of establishing mediation procedures for cross-border disputes in civil and commercial matters. Despite the fact that the obligation lies only for cross-border disputes, the Directive encourages the establishment of mediation procedures for internal conflicts as well.

The promotion of mediation by the European Union has encouraged the proliferation of pilot projects on the implementation of mediation procedures and cooperation projects with the aim of spreading the culture of mediation through Europe. For instance, EIRENE (2012) is a project in which different countries of the EU cooperate in order to implement a communication strategy at the EU level for the promotion of mediation. Its main objective is to develop the culture of mediation as an identity symbol of Europe. Another example is the creation of the European Association of Judges for Mediation (GEMME), which associates professionals of the European Union, Council of Europe, and eventually also the Latin-American countries willing to use alternative dispute resolution systems and specially court-connected mediation measures (European Association of Judges for Mediation; GEMME-España, 2007).

In the directive 52/2008/EC of European Parliament, mediation is promoted as a mechanism which is a quicker, simpler and a more cost-efficient way to solve disputes. This mechanism allows for taking into account a wider range of interests of the parties, with a greater chance of reaching an agreement which will be voluntarily respected. It also allows the preservation of an amicable and sustainable relationship between them. The Commission considered that mediation holds an untapped potential as a dispute resolution method.

Alternative dispute resolution procedures are already a key component of dispute resolution in industrial relations in all the member states. These procedures have demonstrated their usefulness with regard to the resolution of individual and collective disputes related to both conflicts of interest and rights conflicts. However, procedures vary from one member state to another (European Commission, 2002). Also, new procedures, laws, and ADR methods are introduced in different ways. In the Council meeting on employment and social policy in Brussels (2001), the European Council (1999) recognized that non-judicial dispute resolution mechanisms contribute to resolve disputes and play an important role in existing systems of industrial relations. The European Council welcomed the Commission's intention to deepen the understanding of how dispute resolution mechanisms are organized and function in the area of industrial relations. The degree of implementation of this Directive has recently been assessed in order to discover the reasons for its low impact in Europe. The outcome of this research was published in a document titled "Rebooting the mediation directive: Assessing the limited impact of its implementation and proposing measures to increase the number of mediations in the EU", which was presented in February 2014 in Brussels. This report develops the "Paradox of Mediation in the European Union" that highlights that despite the multiple benefits of mediation and the support of the European Union, the European Commission and most of the Governments, mediation has only been used in 1% of the civil and commercial disputes that have arisen in Europe (European Parliament, 2014). As this study suggests, we are living a new phase in the integration of mediation in the judicial systems of the European states. The regulation of mediation is not homogeneous through Europe. Some states have completely legislated the process of mediation. For instance, in United Kingdom, the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Services (ACAS) offer mediation services for any phase of the labor disputes before and after the judicial procedure is open. While some European countries have extensive legal rules on the subject (Lithuania), other countries have no specific provisions pertaining to dispute resolution (the Netherlands), and others already have a rooted tradition of mediation based primarily on self-regulation such as Spain. In Spain, the development of mediation is new, with the first formal proposal developed in 1996, and there is still limited regulation depending on the region and the jurisdiction. There are a few regional laws on mediation and one law at the national level that implements the EU Mediation Directive (Ley 5/2012, de 6 de julio, de mediación en asuntos civiles y mercantiles a través de la cual se implementa en España la Directiva Europea sobre Mediación). Recently, in December 2013, the Spanish government has published a Royal Decree developing certain aspects of this Spanish Act on mediation, such as the Public Registry of Mediators, the compulsory liability insurance, and the requirements for the establishment of on-line mediation procedures for claims below 600€.

From an international research perspective, mediation has been studied in several contexts across different countries, such as: Malaysian Community Mediation (Wall & Callister, 1999); Community and Family Mediation in the People's Republic of China (Wall, Sohn, Cleeton, & Jin, 1995), Community and Industrial Mediation in South Korea (Kim, Wall, Sohn, & Kim, 1993), Japanese Community and Organizational Mediation (Callister & Wall, 1997), and Mediation in the South Africa Construction Industry (Povey, Cattell, & Michell, 2005). Within the European context, several studies on mediation have also been conducted. For instance, Bollen and Euwema (2013) analyzed the important influence of culture and feedback loops on the practice of workplace mediation; Blain, Goodman, and Loewnberg (1987) compared Australia, Great Britain, and the United States on mediation, conciliation, and arbitration and noticed the general lack of international comparative studies on these issues; Rodriguez-Piñero, Rey, and Munduate (1993) emphasized the relevance of non-judicial methods for labor conflict resolution in Western European countries. Some authors have provided an overview of the French legislation regarding mediation and have focused particularly on internal mediation within a private firm (Rojot, Le Franchec, & Landrieux-Kartochian, 2005). Corby (2000) has made comparisons between Great Britain and New Zealand, but considering only unfair dismissal disputes, and De Palo and Harley (2005) have explored the apparent contradiction between a great amount of mediation-related legislation in Italy and the scarce number of mediated cases. De Palo and Harley also conclude that any country seeking to encourage the widespread adoption of mediation would do well to heed the experience of other states.

In the particular context of European industrial relations, there are two interesting studies that compare the different alternative dispute resolution mechanisms in several European countries. On the one hand, "Settling Labor Disputes" (De Roo & Jagtengberg, 1994) is a comparative study that describes and compares the dispute resolution systems available in the field of industrial relations in several countries of the European Union. On the other hand, Valdés Dal-Re (2002) elaborated in 2002 a report for the European Commission on dispute resolution in collective conflicts. However, to benefit from these experiences, literature on mediation should devote extra efforts to describe and analyze how mediation systems are functioning in different countries.

Mediation System in Andalusia

Spain lacked a tradition in the use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) (Munduate, Ganaza, Alcaide, & Peiró, 1994). Rey (1992) mentions several reasons for this lack of ADR. Firstly, the general lack of confidence in third parties, except for judicial authorities, to solve labor conflicts before the establishment of the Spanish democracy; secondly, the rejection among unions to use these procedures, since they were considered to be aimed at replacing the right to strike; thirdly, the utility and proper working of judicial authorities on labor matters; given the high resort to them for conflict resolution, labor courts are highly specialized and effective; fourthly, the overvaluation of judicial decisions to solve labor conflicts; finally, the general understanding that the conflict is not "really" solved until they get a judicial resolution.

It was not until democracy was established and the Constitution (1978) approved, that the freedom of negotiations between unions and companies and the right to carry out industrial actions in organizations were accepted (Munduate, 1993). Since that time, the Spanish society has progressively developed more autonomy for social partners to regulate industrial relations and a higher respect for this collective autonomy. As a consequence, in the 90s there has been an increase in the establishment of ADR to solve labor collective conflicts.

At a national level, the first formal proposal to resort to mediation and arbitration in Spain arose in 1996 and it was called Agreement for Extrajudicial Labor Conflict Resolution (ASEC in its original acronym). The agreement was signed by the largest trade unions in 1993 and the most representative employer associations and counts with the support of the national government. This agreement regulated collective labor conflicts, excluding interpersonal conflicts and conflicts on social security matters. The ASEC respects the competences of other regional ADR systems established in the field of labor disputes. Therefore, local state systems will be considered preferential if so wished by the parties even if that conflict was actually the competence of the ASEC. The positive outcomes of the agreement have encouraged social partners to improve the model. Therefore, the last agreement signed in 2012 has changed its name from Agreement for Autonomous Labor Conflict Resolution instead of extrajudicial, with the aim of highlighting the focus on the dialogue of the parties.

Andalusia is the largest of the 17 autonomous regions in Spain. It is composed of eight provinces which, according to the census of 1st January 2013, have a total population of 8,421,274 people, which represents 18.89% of the population in Spain. According to the Economic and Social Andalusian Council's report on socioeconomic situation in Andalusia on 2011 (CESA, 2012), the number of companies acting in Andalusia on 1st January was 482,334, the number of people over 16 years old was 6,800,725; out of this, 4,017,600 were integrated in the labor market. Of this, 2,627,774 (65.4%) are working and the unemployment rate is 34.6% (EPA, 2014).

The Extrajudicial System for Labor Conflict Resolution in Andalusia (SERCLA) was created by an interprofessional agreement subscribed by the most representative employers' association and the two largest trade unions in Andalusia. The Andalusia Government also signed this agreement, committing to provide the necessary means for the effective development of the system, such as installation administrative facilities, personnel, technical, and material support. It finally came into effect in January 1999. At first, SERCLA was only competent for seeing collective labor conflicts. After the 2009 reform, it extended its competence to certain individual conflicts as well. Since SERCLA tries to promote dialogue, consensus, and co-responsibility of the disputants, it stresses mediation, being that arbitration less extended. In fact, in 2013 there were 1,454 collective labor conflicts and individual conflicts. Out of the 383 brought to SERCLA, only three were for arbitration - this translates as far less than 1% of the whole (SERCLA, 2014).

The mediation service is provided by a mediation team usually composed of four mediators. A genuine characteristic of SERCLA's system is that trade unions and employer's associations design a list of eligible mediators, so that two of them are appointed by the principal employer's association, and the other two by the two largest trade unions' lists, one appointed by each of them. In individual cases, the mediation team is composed of only two mediators, one appointed by the employer's confederation and the other one by the trade unions. Though the mediator team is composed of members appointed by each association, they shall not act as representatives of the disputants; rather, they shall conduct the mediation process to assist the disputants to get their own agreement. Additionally, every mediation is also assisted by a secretary provided by the Andalusian Government. As previously mentioned, the reason for using this particular designation process of mediators is the traditional lack of trust of social partner for third non judicial. Employers and trade unions involved in this system deposit in SERCLA's secretariat a list of at least twenty people who could act as mediators. There is not a strict or drawn-out procedure in appointing the mediators for each case - sometimes they are appointed because they have knowledge on the topic. But in any case, mediators should have participated in the negotiation of the collective agreement that is being discussed (SERCLA, 2014).

The SERCLA offers compulsory mediation training for every mediator. The requirements to become a mediator are: to follow twelve-hour theoretical and practical mediation training and to attend to at least three real mediators as an observer. Once mediators are included in the system, they shall take a re-training at least once every two years during their career as mediators (SERCLA, 2014).

SERCLA deals essentially with the two different types of collective conflicts that can arise between the social and economic partners: rights conflicts, and conflicts of interest (Martínez-Pecino, Munduate, Medina, & Euwema, 2008). Rights conflicts refer to the interpretation or application of norms. There is a rights conflict when a party claims that there has been a violation of a collective agreement or of the provisions of working rules; workers assert that their rights have not been respected. Conflicts of interest are those conflicts that pertain to the establishment of the terms and conditions of employment. Interest disputes would be those that arise when labor and management are involved in negotiating a new collective bargaining agreement, since it tries to specify the terms and conditions of the employment relationship (Devinatz & Budd, 1997). There are two ways of submitting conflicts of interest to SERCLA. One way is usually labeled "general conflict". In this instance the parties request assistance for either an impasse or blockage in the negotiation process or just because they think that mediation can be helpful. The second way, labeled "previous to strike", arises when the impasse has led to a threat of strike.

In rights conflicts, it is compulsory for the claimant to apply to SERCLA before going for adjudication. It is the same situation for conflicts of interest in which there is a threat of strike announced by union organizations. In such situations, SERCLA can act in any other conflict voluntarily submitted by the parties. It is important to emphasize that even though it is mandatory to request mediation under certain types of conflict, it is not compulsory to settle on it.

On the other hand, according to the agreement of the monitoring commission, SERCLA is competent for seeing individual claims regarding professional classification functional mobility and mobility among different categories; individual classification about transfers and displacements; determination of vacation periods; disputes about licenses and working time; and economic and retributive claims derived from the aforementioned (SERCLA, 2009).

Procedure of the SERCLA

Mediation starts with the application of one person or institution. Depending on the type of conflict, mediation shall be requested by different actors. In general conflicts (either rights conflicts or conflicts of interest), mediation can be requested by trade unions and employers' organizations whose scope of action is equal or broader than the scope of the conflict. In conflicts previous to strike, mediation shall be requested by the Strike Committee - the bodies legitimized for starting the strike and the affected employers. The process is launched when the parties submit the application form. Any of the disputants can submit it directly to SERCLA and there is no need to inform the other that they are going to take that action. As well, both parties can submit together. Once the application form is received at SERCLA, if it is considered necessary to rectify some information it will be reverted to the parties so that they can rectify it within the following 5 working days from its receipt. In case it is not rectified before the deadline, the proceedings will be filed.

SERCLA will notify the parties involved and will call them together usually within the following 7 working days from the reception of the submission or the rectification of it. In general, if no agreement is reached within 25 working days the proceedings will be termed as completed finished without agreement. Exceptionally, this time limit could be extended if necessary.

In mediations previous to judicial procedures and individual mediations (that are also a phase of the judicial individual procedure), limitation periods for filing the lawsuit before the employment tribunals are suspended. This is one of the requirements established by the European Directive on Civil and Commercial Matters. This suspension is considered a legal guarantee that protects the right to access to courts. Likewise, in case mediation fails, parties would have time to prepare their lawsuits. However, it is also important to prevent the misuse of mediation as a means for delaying the judicial procedures, so this is the reason why if in 25 days parties have not got to an agreement, the mediation process shall be filed by the Secretary.

Reference Model of the Mediation Process

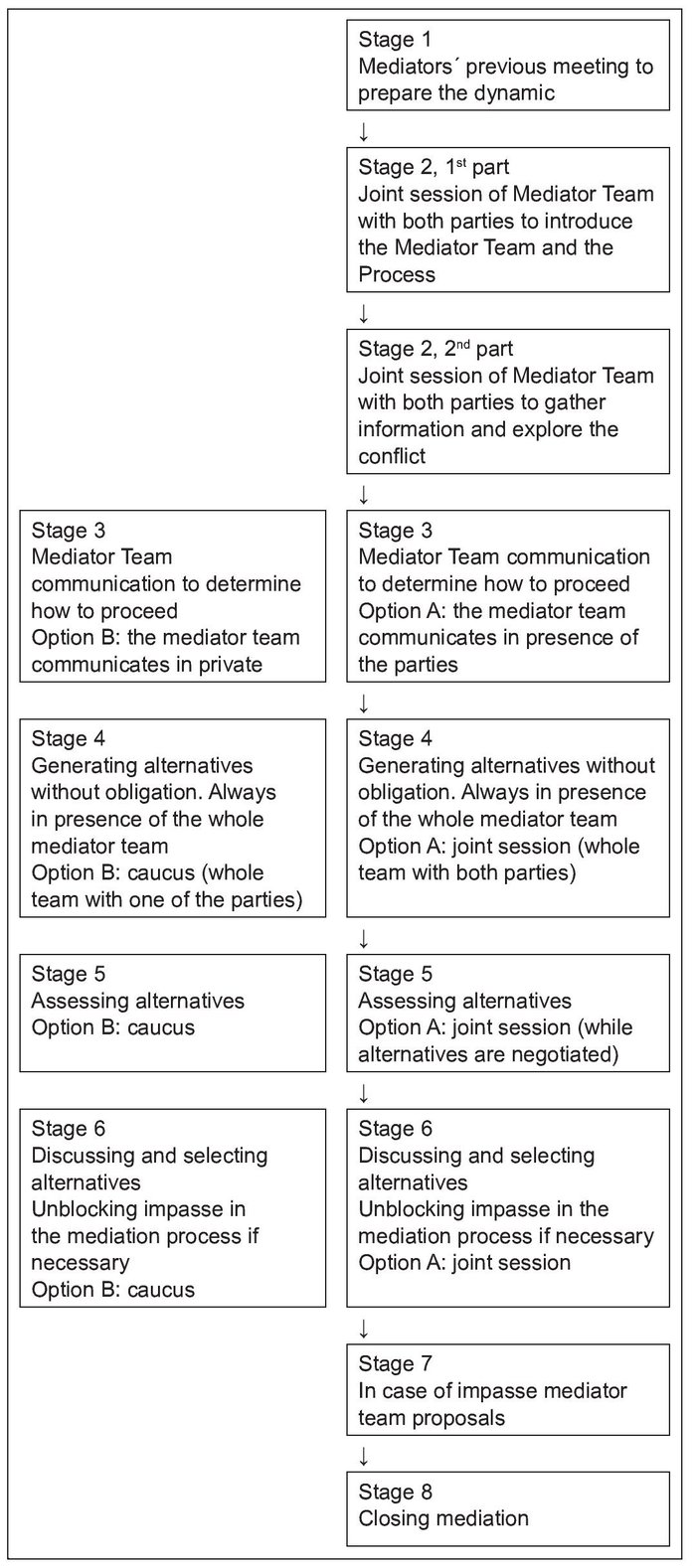

The mediation service is a rather flexible process. The mediation team, in light of the circumstances of the case and the disputants, conducts the mediation in any manner that they consider appropriate. Mediators have autonomy in their interventions and the techniques they apply. Nonetheless, SERCLA has developed a Reference Model for Mediation that we present next (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mediation model in SERCLA

Several aspects of this model are worth emphasizing. First, option A (joint sessions) in which the entire mediator team works with both disputants is preferred to caucus or private sessions. Second, it is important in this model that the mediation team remains together instead of dividing itself (for instance it is necessary for mediators appointed by employers associations to meet with employers and for mediators appointed by union associations to meet with employees) - so that, in case a caucus is considered necessary, it is recommended that the whole team meet with one party at a time (the team will not separate itself). Finally, if it is necessary to tackle the BATNA of the parties, it will be done in caucus. The key feature of the model is the cooperation of the mediators as a team. This requires specific actions during the different stages of the mediation process. We highlight some of the critical moments in the process.

The first stage (mediator's previous preparatory meeting) is oriented around the mediators so that they can prepare themselves to work as a team. Coordination is essential to ensure cooperation among them and to make the parties perceive them as a team. To get it, mediators need to be aware of personal preferences regarding the mediation process, organize diverse team tasks and decide how to conduct the process. The second stage is the first contact with the disputants. Now, mediators need to express to the parties that they are a mediation team and not representatives of the parties.

Observations of 26 mediation cases give indications that mediation teams do differ largely in the degree of cooperation (Martinez et al., 2008). Thus, while some teams prefer to meet some minutes in advance, talk among themselves, and stay together to receive the disputants, others meet directly with the parties. In this latter case, some teams are separated in such a way that the two mediators appointed by employers caucused with managers, and the two mediators appointed by unions caucused with workers. Occasionally, the two mediators appointed by unions separated themselves from worker members of different associations. These non-planned divisions between team members seem to reflect cooperation and cohesion to a lesser extent than those teams that remained together as a team to receive the disputants.

At stage 3, the mediation team has to decide on the course of action. Now, the dilemma for the mediators is how to act and speak with one voice. Should the team always present a unified vision on the mediation, or is it acceptable for the team to have discussions or different opinions in front of the disputants? Our observations give some anecdotal impressions that mediation teams do act differently in this respect and develop different norms indeed. Some teams prefer to meet privately with the aim of sharing information and reaching consensus in the team, whereas other mediation teams do share their perspectives in front of the disputants.

The phases of generating, assessing, and selecting alternatives (stages 4, 5, and 6) are again a critical test of teamwork. We observed that team members who had been mediating together in previous cases and understood each other tried to benefit more from their abilities and supported and assisted other members in their interventions. As an example, we observed a team that had to make a suggestion that was critical for the process to go on to one of the disputants discuss which of the members could exert more influence on that disputant so that he or she could act as voice for the mediators. In contrast, in some mediation teams there were members who acted individually, making comments that took sides for one of the disputants and comments that were not strategically discussed and agreed upon by the team, leading to a complex situation.

Some differences can also be appreciated among teams that remained together (either in presence of both disputants or caucusing with them) and those which continuously separated themselves, in the sense that in the former all members received all the information together, helping to avoid misunderstandings, whereas the latter had a longer chain of communications, leading to greater possibilities of missing and misunderstanding information.

Effectiveness of SERCLA Interventions

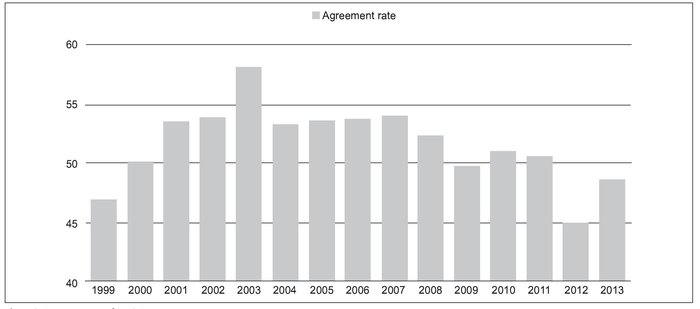

During these first fourteen years that SERCLA has been functioning, 13,400 conflicts have been submitted to the system. These cases affected more than 400,000 companies and more than 3,000,000 employees. It is noticeable that not all cases submitted to SERCLA are finally processed. Among some reasons for this, we can find that the parties did not rectify the application form before the deadline, the claimant desisted from the conflict, the strike was cancelled, or the defendant did not appear. The number of cases submitted to SERCLA has evolved from 299 in 1999, to 1,837 in 2013, 1,454, of which were collective and 383 individual. The percentage of proceedings that were finally processed has also increased from 67.23% in 1999, to 84% in 2013.

In Figure 2, we present the percentage of settlements reached in cases finally processed since the creation of the system (SERCLA, 2013).

Figure 2. Agreement rate of SERCLA.

If we focus on the attendance in conflicts previous to strike, this system has contributed to social peace from 1999: 4,473 agreements have been reached, avoiding the loss of 33.4 million working hours (SERCLA, 2013). This data estimation is based on the information provided in the application forms. In conflicts previous to strike, the claimant must give details of how many companies are affected by the strike, how many employees were convoked for it, and how long it has been predicted to last. Considering this data, it is easy to calculate the working hours saved if the strike is avoided by multiplying the number of workers by the number of strike days and the average of working hours in a day. In cases of indefinite strikes, for the purposes of calculation, it is considered predicted to last for three days.

Considering rights conflicts, 3,993 agreements have been reached in these 14 years, contributing to a reduction of the conflict load in the judicial sphere. It is important to compare this latter result with the ones achieved previously to the existence of this system. Before the creation of SERCLA, there was a mandatory conciliation procedure conducted by CMAC (Center for Mediation, Arbitration, and Conciliation) for conflicts previous to a judicial avenue. We can find a huge difference in the percentage of agreements reached by SERCLA compared to the previous system. With CMAC, 4.62% and 3.76% of agreements were reached in 1997 and 1998 respectively, compared to a rate varying from 37.25% to 32.89% agreements reached by SERCLA from 1999 to 2013 respectively in conflicts previous to a judicial avenue (SERCLA, 2013).

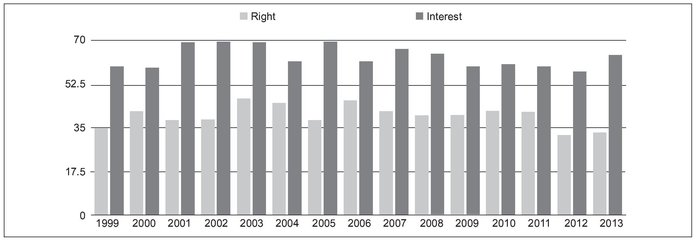

If we compare percentages of agreements between types of conflicts, a substantial difference is appreciated. Rights conflicts get lower settlements rates than conflicts of interest, either they are conflicts of interest previous to a strike process or general assistance in conflicts of interest.

In Figure 3, we compare the evolution of percentages of settlements depending on the type of conflict (SERCLA, 2013).

Figure 3. Percentage of settlements depending on the type of conflict:

Interests & rights.

As we have previously mentioned, not all cases submitted to SERCLA are finally processed. The main cause for anticipated ending of the proceedings is that the defendant does not appear, what is called "intended without effect". Besides these substantial differences in percentages of settlements comparing rights conflicts with conflicts of interest, we find another important difference in percentages of cases in which the defendant does not appear. In rights conflicts, it is more frequent that the defendant does not appear, compared to conflicts of interest. One possible explanation is that rights conflicts, compared to conflicts of interest, tend to be more legalistic and adversarial (Bain, 1997). Therefore, the parties could prefer going to courts instead of searching for an agreement in mediation. When the parties are locked into rigid positions for what they believe to be "right", there is little to trade (Messing, 1993) and this may make them prefer courts to mediation.

Discussion

The main implication for other mediation systems stems from the involvement of both social partners in the creation of SERCLA. As we have previously mentioned, it was created by an inter-professional agreement between the two largest trade unions and the most representative employer association. This agreement was also signed by the Andalusian government as a sign of support and commitment to the system. The implication and involvement of both social partners is essential for the proper functioning of the systems. For example, De Roo and Jagtenberg (2002) reported about an institution introduced by the Dutch government that failed, as it was not developed jointly with the interest groups representing both sides of industry. Implementing a system like SERCLA could be very suitable in contexts with a scarce tradition to use mediation for labor conflict resolution, due to the confidence that it can generate in the disputants.

A second implication is that the composition of the mediation team where mediators are appointed by employers' associations and trade unions and the successful cooperation among its members could serve as a model for cooperation to disputants. Negotiators are used in experienced collective bargaining as an adversarial process of confrontation between groups: employers and employees. Therefore, they may have some negative expectations about mediation, and the level of trust in the process and the other party can be low. For this reason, SERCLA offers a cooperative model between employers and employees in the composition of the mediation teams. Bearing in mind social learning theories and the fact that people can pass on effective styles of behavior to others by social modeling (Bandura, 2001), we consider that the composition of the mediation team in the Andalusia's system offers the disputants a model for cooperation. Cooperating as a real team of mediators appointed from opposed associations can serve as a model to show the disputants that cooperation between them is also possible. Improvement in the relationship and ability to negotiate directly has often been considered potential results of mediation (Wall & Lynn, 1993; Wall, Stark, & Standifer, 2001).

A final implication refers to the ways of dealing with neutrality and impartiality. This issue has evoked intense debates in literature and has been addressed by many authors (Arad & Carnevale, 1994; Bingham & Pitts, 2002; Carnevale & Pruitt, 1992; Murray, 1997; Watkins & Winters, 1997; Wehr & Lederach, 1991). Impartiality and neutrality have often been used as interchangeable concepts. Nonetheless, there are analysts who consider they are different. Impartiality is seen to refer to unbiased opinion or lack of preference in favor of one or more parties in conflict during the mediation process, whereas neutrality refers to the fact that there are not any strongly positive or negative relationships between a mediator and the parties before the mediation occurs (Kleiboer, 1996). An important question is if a mediator should be neutral and if biased mediators would be acceptable for the parties. It can be considered that a mediator who has a previous relationship with one of the parties could not gain the confidence and acceptability of the other disputant and could present biases during the process. However, a mediator who is closer to one side could sometimes be beneficial (Carnevale & Choi, 2000; Carnevale, Cha, & Fraidin, 2004). That close relation could be useful to exert influence over the party. The composition of the mediation team in SERCLA, with an equal number of mediators appointed by each association, offers a good way to preserve neutrality before the mediation. In this sense, the fact that mediators are appointed by the associations of the parties involved allows the parties to feel closer to them and let mediators influence the parties, yet neutrality is achieved by an equal number of mediators appointed by employer and union associations. However, to benefit from this composition of the mediation team, mediators must cooperate to keep impartiality in their interventions during the process. Proper training of mediators by SERCLA regarding this issue is crucial in order to guarantee the success of the system (Wall & Dunne, 2012).

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

1This law excludes labor and community mediation which are referred to specific regulation.

References

1. Arad, S., & Carnevale, P. J. (1994). Partisanship effects in judgments of fairness and trust in third parties in the palestinian-israeli conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 38, 423-451. [ Links ]

2. Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1-26. [ Links ]

3. Barendrecht, J. M., & de Langen, M. (2008). The state of access: Success and failure of democracies to create equal opportunities. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [ Links ]

4. Bingham, L. B., & Pitts, D. W. (2002). Highlights of mediation at work: studies of the national redress evaluation project. Negotiation Journal, 18, 135-146. [ Links ]

5. Blain, N., Goodman, J., & Loewenberg, J. (1987). Mediation, Conciliation and Arbitration. An international Comparison of Australia, Great Britain and the United States. International Labor Review, 126, 179-198. [ Links ]

6. Bollen, K., & Euwema, M. C. (2013). Workplace Mediation: An Underdeveloped Research Area. Negotiation Journal, 29, 329-353. [ Links ]

7. Brett, J. M., Goldberg, S. B., & Ury, W. L. (1990). Designing systems for resolving disputes in organizations. American Psychologist, 45, 162-170. [ Links ]

8. Callister, R. R., & Wall, J. A. (1997). Japanese Community and Organizational Mediation. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41, 311-328. [ Links ]

9. Carnevale, P. J., Cha, Y. S., Wan, C., & Fraidin, S. (2004). Adaptive Third Parties in the Cultural Milieu. In M. Gelfand & J. Brett (Eds.), The Handbook of Negotiation and Culture. California: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

10. Carnevale, P. J., & Choi, D. (2000). Culture in the mediation of international disputes. International Journal of Psychology, 35, 105-110. [ Links ]

11. Carnevale, P. J., & Pruitt, D. G. (1992). Negotiation and mediation. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 561-571. [ Links ]

12. Carretero, E. (2011). Mediación. In H. Soleto, Mediación y resolución de conflictos: Técnicas y ámbitos. Madrid: Tecnos. [ Links ]

13. CESA (Consejo Económico y Social de Andalucía) (Andalusia Social and Economic Council) (2012). Informe sobre la situación socioeconómica de Andalucía (Report on socioeconomic situation in Andalusia). Sevilla: Consejo Económico y Social de Andalucía. [ Links ]

14. Corby, S. (2000). Unfair Dismissal Disputes: a Comparative Study of Great Britain and New Zealand. Human Resource Management Journal, 10, 79-92. [ Links ]

15. De Palo, G., & P. Harley. (2005). Mediation in Italy: Exploring the Contradictions. Negotiation Journal, 21, 469-479. [ Links ]

16. De Roo, A. J. de, & Jagtenberg, R. W. (1994). Settling Labour disputes in Europe. Deventer, Boston: Kluwer Law and Taxation. [ Links ]

17. De Roo A. J. de, & Jagtenberg, R. W. (2002). Mediation in The Netherlands: Past - Present - Future. Electronic Journal of Comparative Law, 6, 127-145. [ Links ]

18. Devinatz, V. G., & Budd, J. W. (1997). Third parties dispute resolution. Interest disputes. In D. Lewin, D. J. B. Mitchell, & M. A. Zaidi, The human resource management handbook. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [ Links ]

19. EIRENE (2012). Retrieved from http://www.mediation-eirene.eu/mediation-in-europe/spain/?lang=es. [ Links ]

20. EPA (2014). Encuesta de Población Activa 2014. Retrieved from http://www.ine.es/daco/daco42/daco4211/epa0214.pdf. [ Links ]

21. European Commission (2002). Green paper on alternative dispute resolution in civil and commercial law (COM 2002, 196 final). Brussels: European Commission. [ Links ]

22. European Commission (2004). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters (COM 2004, 718 final). Brussels: European Commission. [ Links ]

23. European Council of Tampere (1999, October 15/16). Presidency conclusions. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.eu.int/summits/tam_en.htm. [ Links ]

24. European Parliament (2014, January). Rebooting the mediation directive: Assessing the limited impact of its implementation and proposing measures to increase the number of mediations in the EU. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2014/493042/IPOL-JURI_ET(2014)493042_EN.pdf. [ Links ]

25. European Union (2008, May 24). Directive 2008/52/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters. Official Journal of the European Union, L 136. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:136:0003:0008:En:PDF. [ Links ]

26. Fundación Wolters Kluwer (2012). Informe 2012 del Observatorio de la Actividad de la Justicia. Retrieved from http://www.fundacionwolterskluwer.es/es/Justicia12.asp [ Links ]

27. GEMME-España (2007). European Association of Judges for Mediation. Retrieved from http://www.gemme.eu/en. [ Links ]

28. Goldberg, S. B., Sander, F. E. A., & Rogers, N. H. (1999). Dispute resolution, Negotiation, Mediation and Other processes. New York: Aspen Law. [ Links ]

29. Kim, N. H., Wall, J. A. Sohn, D., & Kim, J. S. (1993). Community and Industrial Mediation in South Korea. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 37, 361-381. [ Links ]

30. Kleiboer, M. (1996). Understanding success and failure of international mediation. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 40, 360-389. [ Links ]

31. Martínez-Pecino, R., Munduate, L., Medina, F. J., & Euwema, M. C. (2008). Effectiveness of Mediation Strategies in Collective Bargaining. Industrial Relations, 47, 480-495. [ Links ]

32. Messing, J. K. (1993). Mediation: an intervention strategy for counsellors. Journal of Counseling and Development, 72, 67-72. [ Links ]

33. Munduate, L. (1993). A Psychosocial approach to the study of Conflict and Negotiation in Spain: A review. Psicothema, 5, 261-275. [ Links ]

34. Munduate, L., Ganaza, J., Alcaide, M., & Peiró, J. M. (1994). Spain. In M. A. Rahim & A. A. Blum, Global Perspectives on Organizational Conflict. Connecticut: Praeger. [ Links ]

35. Murray, J. (1997). The Cairo stories: some reflections on conflict resolution in Egypt. Negotiation Journal, 13, 39-60. [ Links ]

36. Povey, A., Cattell, K., & Michell, K. (2005). Mediation Practice in the South African Construction Industry: The Influence of Culture, the Legislative Environment, and the Professional Institutions. Negotiation Journal, 21, 481-493. [ Links ]

37. Rey, S. (1992). La Resolución Extrajudicial de Conflictos Colectivos Laborales (The extrajudicial ways for labor conflict resolution). Sevilla: Consejo Andaluz de Relaciones Laborales. [ Links ]

38. Rodríguez-Piñero, M., Rey, S., & Munduate, L. (1993). The intervention of Third Parties in the Solution of Labor Conflicts. European Work and Organizational Psychologist, 3, 271-283. [ Links ]

39. Rojot, J., Le Flanchec, A., & Landrieux-Kartochian, S. (2005). Mediation within the French Industrial Relations Context: The SFR Cegetel Case. Negotiation Journal, 21, 443-467. [ Links ]

40. SERCLA (2009). Sistema Extrajudicial de Resolución de Conflictos Laborales de Andalucía. Memoria 2009 (Extrajudicial System for Labor Conflict Resolution in Andalusia. Report 2009). Sevilla: Consejo Andaluz de Relaciones Laborales. [ Links ]

41. SERCLA (2013). Sistema Extrajudicial de Resolución de Conflictos Laborales de Andalucía. Memoria 2013 (Extrajudicial System for Labor Conflict Resolution in Andalusia. Report 2013). Sevilla: Consejo Andaluz de Relaciones Laborales. [ Links ]

42. SERCLA (2014). Sistema Extrajudicial de Resolución de Conflictos Laborales de Andalucía. Carta de Compromisos de la Actuación Mediadora 2014 (Extrajudicial System for Labor Conflict Resolution in Andalusia. Report 2005). Sevilla: Consejo Andaluz de Relaciones Laborales. [ Links ]

43. Valdés Dal-Re, F. (2002). Labour conciliation, mediation and arbitration in European Countries. Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales. [ Links ]

44. Verdonschot, J. H., Barendrecht, M., & Kamminga, P. (2008). Measuring Access to Justice: The Quality of Outcomes (Tilburg University Legal Studies Working Paper No. 014/2008; TISCO Working Paper No. 007/2008). Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1298917 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1298917. [ Links ]

45. Wall J. A., & Callister, R. R. (1999). Malaysian community mediation. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 43, 343-365. [ Links ]

46. Wall, J. A., & Dunne, T. C. (2012). Mediation Research: A current Review. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56, 217-243. [ Links ]

47. Wall, J. A., & Lynn, A. (1993). Mediation: a current review. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 37, 160-194. [ Links ]

48. Wall, J. A., Sohn, D. W. Cleeton, N., & Jin, D. J. (1995). Community and Family mediation in the People's Republic of China. International Journal of Conflict Management, 6, 30-47. [ Links ]

49. Wall, J. A., Stark, J. B., & Standifer, R. L. (2001). Mediation: a current review and theory development. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45, 370-391. [ Links ]

50. Watkins, M., & Winters, K. (1997). Intervenors with interests and power. Negotiation Journal, 13, 19-142. [ Links ]

51. Wehr, P., & Lederach, J. P. (1991). Mediating Conflict in Central America. Journal of Peace Research, 28, 85-98. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Francisco J. Medina.

Facultad de Psicología.

Universidad de Sevilla.

C/ Camilo José Cela, s/n.

41018-Sevilla.

E-mail: fjmedina@us.es

Manuscript received: 15/12/2013

Revision received: 21/09/2014

Accepted: 25/10/2014