Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones

versión On-line ISSN 2174-0534versión impresa ISSN 1576-5962

Rev. psicol. trab. organ. vol.31 no.1 Madrid abr. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rpto.2015.02.004

Actionable trust in service organizations: a multi-dimensional perspective

La confianza como acción en las empresas de servicios: perspectiva multidimensional

Hila Chalutz Ben-Gala, Shay Tzafrirb and Simon Dolanc

aAfeka Tel Aviv Academic College of Engineering, Israel

bUniversity of Haifa, Israel

cESADE Business School, Spain

ABSTRACT

Purpose. The paper explores attitudinal and behavioral antecedents of trust and respective outcomes within the service industry at multiple levels of analysis.

Method. Data were obtained from academic and administrative service providers (n = 76) and clients (n = 868) using paper-and-pencil and on-line questionnaires.

Findings. Individual, dyadic and organizational factors throughout service delivery affect trust as a behavior. Value fit between service providers and clients contributed to trust as a behavioral action.

Implications. Our findings confirm that success of service delivery is a multi-dimensional phenomenon. It confirms that actionable trust is a dominant factor in service success, thus calls for the need to pay attention to the relational aspect of service encounters. Finally, value fit between clients and service providers is crucial in achieving trust throughout the service interaction.

Originality. The study provides a management tool for measuring action based trust within service organizational context.

Key words: Trust. Justice Service. Values. Fit. Stakeholders.

RESUMEN

Objetivo. Este trabajo explora los antecedentes actitudinales y comportamentales de la confianza y sus consecuencias en el sector de servicios a diversos niveles de análisis.

Método. Se obtuvieron datos de proveedores de servicios académicos y administrativos (n = 76) y clientes (n = 868) mediante cuestionarios de papel y lápiz y online.

Resultados. Factores individuales, diádicos y organizativos afectan a la confianza como comportamiento en todo suministro de servicios. El ajuste de valores entre los proveedores de servicios y clientes contribuye a la confianza como acción comportamental.

Implicaciones. Nuestros resultados confirman que el éxito en el suministro de servicios es un fenómeno multidimensional. Confirma que la confianza como acción es un factor dominante en el éxito en los servicios, lo que plantea la necesidad de prestar atención al aspecto relacional de los encuentros de servicio. Por último, el ajuste de valores entre clientes y proveedores de servicios es fundamental para lograr la confianza en toda interacción en la prestación de servicios.

Originalidad. El estudio aporta una herramienta de gestión para medir la confianza centrada en la acción en el contexto de las empresas de servicios.

Palabras clave: Confianza. Justicia. Servicio. Valores. Ajuste. Accionistas.

How does one measure the success of modern organizations? More specifically, how does one measure the success of service organizations? Because of the centrality of clients in service settings (Rust & Huang, 2012), what would be the relative importance and outcome of long lasting successful dyadic relationship in a service environment? This paper examines the trust concept in service organizations by presenting a multi-level model for exploring and measuring service drivers.

The concept of trust have been studied and explored. It has been proved that a trusting relationship assists in both group performances, as well as in organizational performance (Brower, Lester, Korsgaard, & Dineen, 2009; Hempel, Zhang, & Tjosvold, 2009; Mach, Dolan, & Tzafrir, 2010; Zaheer, McEvily, & Perrone, 2007). This paper focuses on understanding and measuring the "trust-informed actions" (Dietz & Den Hartog, 2006, p. 564), both at the organizational and the dyadic levels, and their impact in a service setting.

We explore this in order to differentiate actionable trust from organizational and dyadic trust and their role in organizational context. Furthermore, we emphasize the role of trust, because in service settings, which are based on dyadic interactions, trust based on informed actions is key in achieving effective organizational results.

Service settings are a delicate environment. One reason is the key role stakeholders play in service organizations (Van Buren III & Green-wood, 2011; Verbeke & Tung, 2012). In order to enhance service delivery, understanding the stakeholder's contribution is essential (Tzafrir, Chalutz Ben-Gal, & Dolan, 2012; Van Buren & Greenwood, 2011). For instance, stakeholder's input, such as accessible resources (Verbeke & Tung, 2012), social and environmental agenda (Russo & Perrini, 2010), inter-organizational potential collaboration (Savage & Bunn, 2010), as well as others, might assist any output in service organization.

Within service settings, client feedback and long term loyalty is also of utmost importance (Armenakis & Harris, 2009; Harris & Goode, 2004). Building successful client relationships based on trust, whether with internal or external partners, is an important, yet challenging phenomenon, in modern organizations (Czarniawska & Mazza, 2003) and even more so in service organizations (Reynolds & Beatly, 1999). Moreover, one cannot overlook the importance of dyadic interaction between service providers and their clients (Chuang & Liao, 2010; Coulter & Ligas, 2004; Liao, Toya, Lepak, & Hong, 2009; Liao, Yen, & Li, 2011). Despite extensive research conducted in evaluating various factors separately and their role in service success, as well as extensive research on internal and external factors in service settings (Chandon, Leo, & Philippe, 1997; Hitt, Bierman, & Shimizu, 2011; Liao et al., 2011), little attention has been given to evaluate the conditions that impact action-based trust. Our paper examines the effect of discrete context (Johns, 2006), and explores behavioral based trust (Dietz & Den Hartog, 2006) on service outcomes within the service industry context (Johns, 2006).

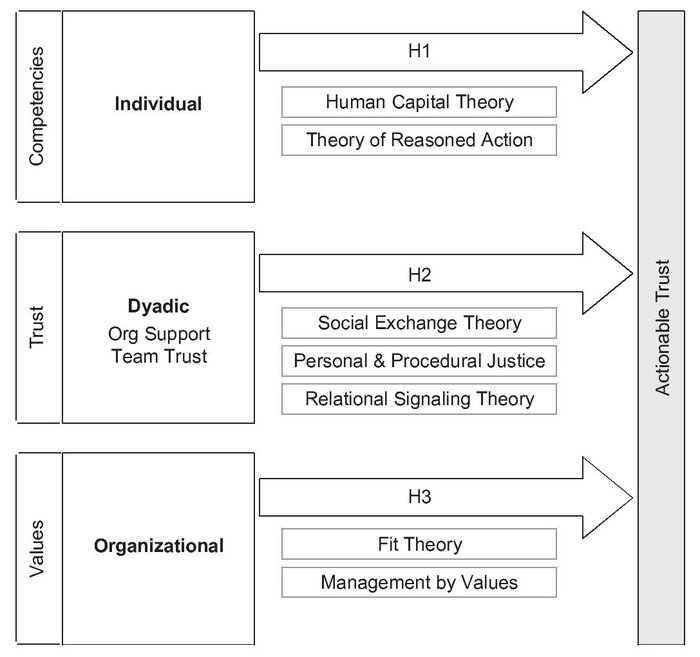

Figure 1. Research Model

Theory and Hypotheses

A substantial amount of theoretical and empirical work has suggested that trust is also a critical factor in inter-organizational collaboration (Alter & Hage, 1993; Bromiley & Cummings, 1996; Currall & Judge, 1995; Fichman & Levinthal, 1991; Jarillo, 1988). It has been argued that trust has a positive effect because it strengthens dyadic ties (Fichman & Levinthal, 1991), speeds contract negotiations (Reve, 1990), and generally reduces transaction costs (Bromiley & Cummings, 1996). Additional research revealed that trust affects managerial problem solving (Zand, 1972), openness and receptivity (Butler, 1991), affective commitment (Herscovitch & Mayer, 2002), and risk taking (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995). Furthermore, it has been found that trust boosts performance of working teams (Bijlsma-Frankema, De Jong, & Van de Bunt, 2008). Nevertheless, most social psychology studies focus on trust as a belief or trust as an intention, neglecting the importance of trust as an action. Dietz & Den Hartog's (2006) work sheds light on trust also from a behavioral perspective. The authors conceptualize the process of trust as (at least) three "phases" of trust: trust - the belief, trust - the decision, and trust - informed actions (Dietz & Den Hartog, 2006, p. 564). Therefore, our research model focuses on various antecedents of trust as an action.

In service settings, it was found that trust enables a long-lasting relationship. Johnson and Grayson (2005) found that satisfaction with previous interactions contributes to trust. The authors proposed that client satisfaction (in financial services industry) is primarily based on core aspects of service delivery and found support for a relationship between trust and sales effectiveness. Others found support for the positive relationship between trust and other aspects in the service industry (Kantsperger & Kuntz, 2010; Park, Lee, Lee, & Truex, 2012). From a client perspective, trust becomes crucial in many relational exchange situations and reduces the perceived risk of the service outcome (Berry, 2002; Laroche , Ueltschy, Abe, Cleveland, & Yannopoulos, 2004). For example, the results of surgery cannot be inspected in advance. Often the outcome is irreversible and in some cases the customer faces the risk of negative long-term consequences (Kantsperger & Kuntz, 2010). Hence, the client must have trust in the expertise of the surgeon.

Trust in the entire company becomes particularly relevant in industries, where the service is performed by different and changing service personnel, like service chains (Kandampully, 2002). The client generally has to trust the company to employ well-trained employees only who are capable of fulfilling his needs and expectations. Therefore, trust serves as a means to reduce transaction costs in terms of search, information, or bargaining costs in the relational exchange between the customer and the service company (Williamson, 1993). For example, a recent study by Park et al. (2012) found that communication effectiveness, functional and technical service qualities, and trust are associated with the client's relationship commitment, which is in turn critical for the project success and building longer term relationships within a service delivery setting.

Organizations need to place increasing importance upon learning new capabilities and developing individuals to perform in new and more complex ways (Lawler, 1993). Given pressures for both efficiency and flexibility in modern working environment, service organizations are increasingly seeking ways to enhance individual and group-based competency-based-behaviors (hereafter: "competencies"), in line with exploring different work models (Lepak & Snell, 1999, p. 31). Human Capital Theory is essential in exploring and under standing the individual contribution within the service organization and its influence on a trusting environment (Tepper, Lambert, Henle, Giacolone, & Duffy, 2008). Thus, enhancing and adjusting the human capital to the organizational context (Johns, 2006) becomes an important challenge organizations are faced with and even more so in service settings.

Research findings emphasize the connection between individual competencies and some negative examples of client's behavior. Moreover, service providers and client's personalities have been found to play a crucial role in the success of service delivery (Simsarian Webber, Payne, & Taylor, 2012). In more recent studies, competencies were examined and proved to be of utmost importance in service settings. For example, Asing-Cashman, Gurung, Limby, & Rutledge (2014), whose research focus on service provider's competencies in educational settings, show that specific competencies which the service provider holds were significant predictors of attitudes of clients throughout service delivery (Asing-Cashman et al., p. 66).

In line with the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Madden, 1986), we suggest that individual intentions and behaviors have also meaningful relationship on actionable trust concept. We propose that meaningful behaviors, such as trusting actions (Dietz & Den Hartog, 2006), evolve from individual competencies (Lawler, 1993) and high levels of individual commitment (Hollenbeck, Williams, & Klein, 2001). In line with Dietz and Den Hartog (2006) framework, we propose that individual competencies contribute to explain trust as an action (p. 564). Thus, we hypothesize that:

H1: High level of competencies throughout the service delivery process will result in high level of actionable trust.

In a service delivery setting, which is based on dyadic interactions, trust and justice play a major role. The existence of trusting relationships within organizational settings assists in both group performance as well as in organizational performance as a whole (Brower et al., 2009; Hempel et al., 2009; Korsgaard, Brower, & Lester, 2015; Mach et al., 2010; Zaheer et al., 2007).

As an attitude or belief, trust has cognitive, affective, and intentional components (Korsgaard et. al., 2014). The cognitive component reflects the trustor's beliefs about the character and intentions of the trustee, which is based on the trustor's preexisting expectations as well as assessments of the characteristics of the other party, the quality of the relationship itself, and other situational variables that are likely to influence the relationship. When evaluating the other party, there is likely to be an assessment of trustworthiness -that is, ability, benevolence, and integrity (Mayer et al., 1995)- as well as predictability (Mishra, 1996). The affective component reflects the positive affective associations toward the trustor, the relationship, and the outcomes of the relationship (McAllister, 1995). Furthermore, trust carries an intentional implication regarding the willingness to make one vulnerable, which gives rise to trusting behavior, such as delegation and information sharing. Note that factors that help shape those beliefs (e.g., perceptions of trustworthiness; Mayer et al., 1995) and feelings (e.g., emotional investments; McAllister, 1995) and the actions that flow from are considered separate constructs that are antecedent to or consequences of a trusting attitude (Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, & Ng, 2001; Mayer et al., 1995).

Social Exchange Theory and Relational Signaling Theory help to explain the effect of trust as a belief (Dietz & Den Hartog, 2006) on actionable trust. Social Exchange Theory (Blau, 1964) attempts to explain relationships that entail unspecified future obligations and generates an expectation of some future return for contribution (Menguc, 2000). Therefore, high level of trust will influence the "positive two-way relationship" (Harter,Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002, p. 269). For instance, trust is key in social exchange and renders the basis for relational contracts (Konovsky & Pugh, 1994), which results in reciprocity, and therefore meaningful in a dyadic relationship. Also, Gouldner (1960) discussed the norm of reciprocity as a "mutually contingent exchange of benefits between two or more units..." (p. 164) and suggested that people will, above all, attempt to avoid over-benefiting from their socially supportive interactions, which is key in understanding dyadic interactions.

We suggest that as trust the belief level raises throughout service interaction, the client is gaining confidence and positive mutual feelings such as commitment and loyalty (Harris & Goode, 2004) and, as a result, positively reciprocates. Furthermore, based on Relational Signaling Theory (Six, 2007), trust is construed as an interactive process in which both individuals learn about each other's trustworthiness in different situations. In service settings, this is of utmost importance because of the potentially long term relations between clients and service providers (Chandon et al., 1997; Gutek, Bhappu, Liao-Troth, & Cherry, 1999; Webber & Payne, 2012).

Moreover, in order to gain a wider perspective on trust as a belief, we accept the importance of justice in building trusting relationships. We acknowledge Colquitt's (2001) contribution within this respect. Justice in organizational settings is described as "focusing on the antecedents and consequences of two types of subjective perceptions: (a) the fairness of outcome distributions or allocations or (b) the fairness of the procedures used to determine outcome distributions or allocations" (Colquitt, 2001, p. 425). A more recent meta-analysis study summarized the justice literature at the turn of the millennium (Colquitt et. al., 2013). This study is based upon a review of 493 independent studies on the topic of justice. With respect to social exchange theory, the results revealed a significant relationship between justice and trust. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2: High level of trust as a belief and justice throughout the service delivery process will result in high level of actionable trust.

A substantial amount of theoretical and empirical work has given attention to the meaning of organizational values and their effect on individuals, as well as on organizations as a whole (Devos, Spini, & Schwartz, 2002; Schwartz & Rubel, 2005). For instance, values have been used as a management tool in modern organizations. We suggest that value congruence between key stakeholders influences actionable trust behaviors. Thus, fit, or lack thereof, between the personal values of service providers and those personal values of their clients influence trusting behaviors.

The concept of fit was examined by Nadler and Tushman (1980). The researchers defined fit, or "congruence", as "the degree to which the needs, demands, goals, objectives, and/or structures of one component are consistent with the needs, demands, goals, objectives, and/or structures of another component" (p. 45). The fit concept continues to be a central concept examined intensively in the Psychology and Organizational Behavior literature. For example, Cable and Edwards (2004) examined complementary and supplementary fit within the person-environment fit paradigm. They examined the two types of fit using psychological need fulfillment and value congruence as prototypes. They provide an integrated fit model which predicts various organizational outcomes such as organizational supplies, personal values, and organizational values (Cable & Edwards, 2004). In a later study, the researchers empirically expand on previous research which examines value congruence, or fit, and the means by which it leads to positive outcomes. The authors develop and test a theoretical model that integrates four key explanations of value congruence effects: communication, predictability, interpersonal attraction, and trust. They use these constructs to explain the process by which value congruence relates to job satisfaction, organizational identification, and intent to stay in the organization. They prove that fit in individual and organizational values that lead to outcomes are explained primarily by the trust that employees place in the organization and its members, followed by communication and interpersonal attraction (Edwards & Cable, 2009).

Recent studies explored the link between personal and organizational values. For example, Auster & Freeman (2013) analyze the relationship between individual values and organizational values. Their analysis reveals that the ''value fit'' approach is limited in various organizational contexts, therefore calling for a deeper exploration of the nature of values. Another recent example of an exploration of the nature of the match, or fit, between personal values and organizational values can be found in Van Quaquebeke, Graf, Kerschreiter, Schuh, & Dick (2014). They too, as did Cable and Edwards (2004) and Edwards and Cable (2009), recognized that person-organization fit provides the foundations for organizational effectiveness.

With these theoretical understandings, and considering the complex environment of service settings, we suggest that values are of utmost importance, especially when service delivery is at stake, and especially in the higher education arena. First, because they reflect the organizational complexity, a key feature in a service delivery process. Second, because they assist in achieving the daily professional efforts and even more so when multiple stakeholders are involved, therefore assisting in creating or destroying an expected fit. Third, they assist in the process of "redesign of culture" (Dolan & Garcia, 2002, p. 102), which is extremely relevant when a service organization and stakeholders are involved. Taking all of the above, we suggest a positive link between high level of fit in organizational values and actionable trusting behaviors. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H3: High level of fit in values throughout the service delivery process will result in high level of actionable trust.

Method

We included on-line questionnaires because of the specific organizational context that is technology driven and includes relatively young individuals (client mean age was 26). Since the on-line surveys naturally yield a lower response rate (Fricker, Galesic, Tourangeau, & Yan, 2005), we complemented them with a paper-and-pencil version. The decision to use "traditional" pencil-and-paper data collection tools originated from our wish to measure separately two samples (i.e., clients and service providers), as well as to gain acceptable response rate results (Baruch & Holtom, 2008; Donovan, Drasgow, & Probst, 2000).

Sample

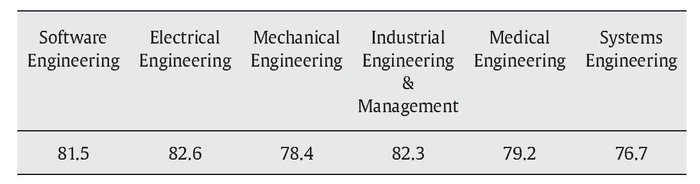

Our sample included both service providers as well as clients. Service providers sample included two groups: academic service providers and administrative service providers. We sampled 76 service providers of both academic and administrative profession, resulting in an acceptable 30% response rate (Baruch & Holtom, 2008). The average age of the respondents was 45 years (SD = 10.5), 51 percent were female respondents, and the average tenure with the organization was 7 years (SD = 4.8). The clients who participated in the study included two groups: active students, i.e., currently involved in active coursework, and alumni, i.e., students that successfully completed their studies within the last five years. The sample included 868 clients, yielding a 44% response rate. About 66% of this group included active students. The average age of clients was 27.05 (SD = 5.64). Seventy-seven percent of the clients were male of whom 74% were single. Fifty-six percent of the clients were working in organizations along with their studies. Responding clients had an average grade of 80.99 (SD = 7.47), comparable to the college average grade of 80. The following table provides data regarding client's average final grade by department of study (SD = 8.28):

Measurement

We used two questionnaires in order to evaluate research constructs: client and service providers. Additionally, external judge ratings were used to measure the viability of value fit by generating an index.

Independent Variables

Competencies were measured by taking clients final academic grades with a mean score of 80.99 (SD = 7.47). We believe this data reflects the objectively output of the interaction between individual motivation, skills, ability, and behavior (Bettencourt, Gwinner, & Meuter, 2001; Brown & Lam, 2008) of both service providers and clients. Precise measurement of competencies, through to the client's final grade, encompasses all data, perceptions, and behaviors and results in the final output (i.e., final grade)1.

Trust was measured at two levels: organizational and individual. At the organizational level, we measure organizational trust using a short version of Tzafrir & Dolan's (2004) questionnaire (Mach et al., 2010). The measurement of dyadic trust at the individual level was based on Mishra & Mishra's scale (1994). Participants were asked to rate items on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Sample questions include: "My team members are totally honest with me" and "My peers share important information with me". Organizational trust and team scales reliability was = .90 and = 96 respectively. In order to gain a wider perspective, within the measurement of trust, we also measured organizational justice and organizational support. We based our measurement on Colquitt's (2001) scale for measuring justice. Sample question include: "To what extent the organization treats you with respect?" and "To what extent the service delivery process is based on precise information?" Scale reliability was α = .89 (interactional justice) and α = .82 (procedural justice). Organizational support was based on Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa's (1986) scale. We used eight-item on a 1-5 Likert scale with reliability of α = .78. Sample question include: "To what extent the organization values my contribution?"

We applied a three-step approach for values measurement2. First, raters (both service providers and clients) were presented with a list of 22 organizational values derived from the eight typologies of culture in the Competing Values Framework (Cameron & Quinn, 1999). Examples of the values in the list included: freedom to act, performance orientation, competitiveness, control, uniqueness, etc. Evaluators were asked to rate the existence of this value in the organization on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Second, we asked four judges who are senior policy makers in the organization (president, chief executive officer, department head and the dean of students affairs), to rank eight types of organizational cultures as the desired organizational culture. Results yielded an agreement on three types of cultures (above 20%). We then derived 6 leading values out of the complete list of 22 values: personal initiative, authority delegation, cooperation, change and dynamics, labor relations, employee satisfaction. Third, in order to measure value fit between service providers and clients' rating of the above 6 values, we calculated a "fit score"3.

Dependent Variable

We measured actionable trust using a single question, which reflects a trusting behavioral act: "I provided my friends and family with a recommendation on The College as a competent academic institution" (Yes/No). First, an actual recommendation is reflected by a variety of perceptions, attitudes as well as a specific trusting behavior on behalf of clients and service providers alike (Simsarian et al., 2012). Second, we found it a suitable measurement tool in a service setting that reflects actual meaningful behavior (Brown & Lam, 2008).

Control Variables

We measured several control variables representing the individual level (for example, age, seniority in organization), unit level (for example, department, year of study), and organizational level (for example, organizational support, type of service sector, number of employees).

Results

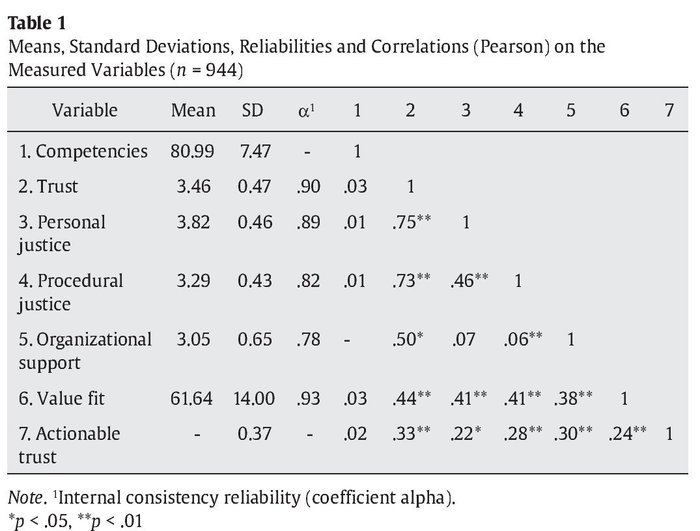

Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and correlations between research variables.

In line with our hypothesis, trust positively correlates with personal justice (r = .75, p < .01), procedural justice (r = .73, p < .01), and organizational support (r = 50, p < .05). Trust is also correlated with value fit (r = .44, p < .01). As predicted, value fit positively correlates with trust (r = .44, p < .01), personal and procedural justice (r = .41, p < .01), and with organizational support (r = .38, p < .01). Accor dingly, value fit positively correlates with actionable trust (r = .24, p < .01). When examining the control variables and their impact on the study's results, some interesting findings are detected. First, a negative correlation was found between client's age and trust, as well as personal justice (r = -.22, p < .01, r = -.18, p < .01, respectively). One explanation might be provided by the fact that the younger one's age, the higher their innocence level is, which may be explained by higher trust in the organization (Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2012).

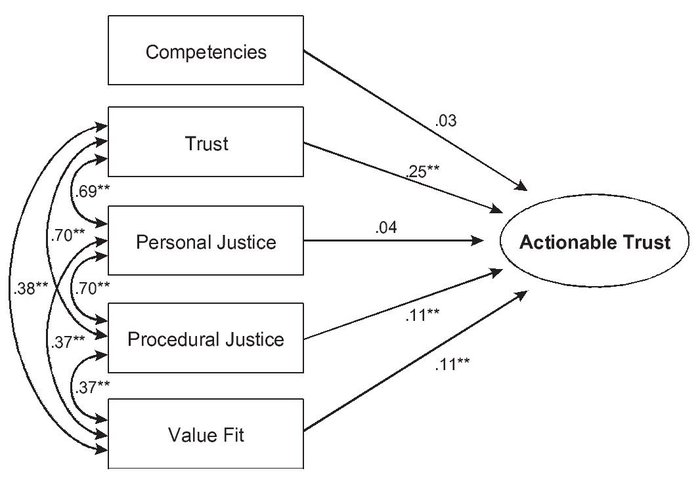

In order to test our hypotheses, we calculated a SEM (structural equation model; see Figure 2) using the AMOS software. Model results yielded reasonable fit indices: CFI = .99., NFI = .99., RMSEA = .04, as well as the factor items and their respective loadings. Bootstrapping procedure was performed in order to adjust for the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable. We did not find support to our first hypothesis that proposed that high level of competencies throughout the service delivery process would result in high levels of actionable trust - therefore, H1 was rejected.

Figure 2. Structural Equation Model

Note. Following standard path notation, observed variables

are denoted as squares, latent variables are denoted as circles, regression weights are indicated by

one-headed arrows, and correlations are represented by two-headed arrows. For ease of presentation,

the path coefficients corresponding to the exogenous variables (age, education) are not presented

(these can be found in Table 1), nor are the factor items and their respective loadings. Bootstrapping

procedure was performed in order to adjust for the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable.

Standardized coefficients are presented. Model fit indices:

CFI = .99, NFI = .99, RMSEA = .04. ns = p > .01, *p < .05, **p < .001.

Our second hypothesis was that a high level of dyadic trust throughout the service delivery process would result in high levels of actionable trust. Study results demonstrated a full confirmation of this hypothesis (β = .25, p < .001). We then aimed to explore the organizational drivers throughout the service delivery process. Therefore we hypothesized that a high level of fit in values throughout the service delivery process will result in high levels of actionable trust (Hypothesis 3). This hypothesis was fully supported as results indicate a significant relationship between the two variables (β = .11, p < .001).

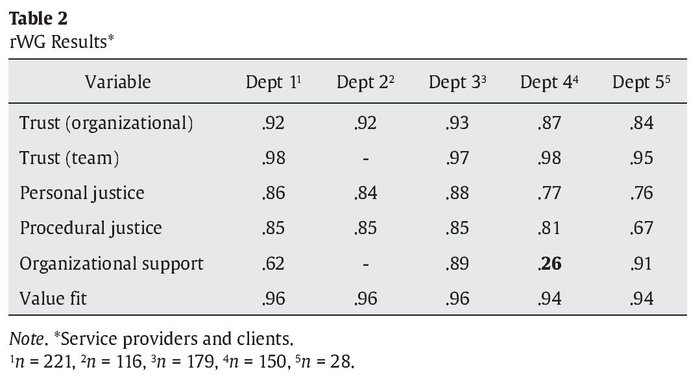

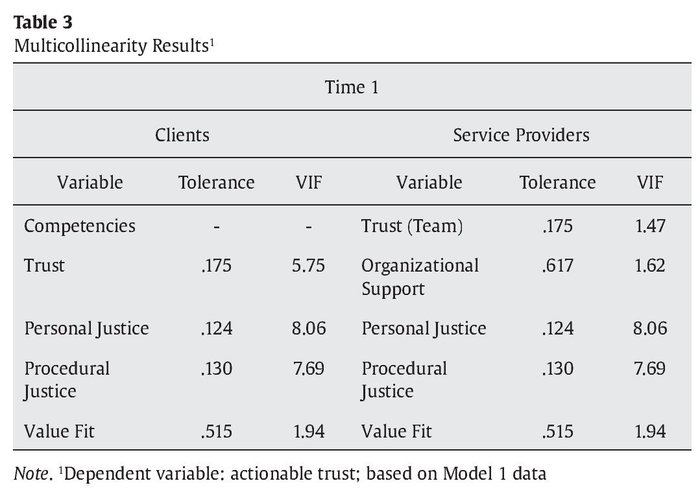

Method Bias

In this study we implemented two techniques in order to test for method biases. First, we assessed the level of agreement among the judgments made by the study's group of judges (both service providers and clients) "on a single variable in regard to a single target", or what is referred to as the rWG measure. Second, we tested for multicollinearity in order to eliminate the presence of highly intercor-related predictor variables in the regression models and to avoid or invalidate some of our basic theoretical assumptions. Tables 2 and 3 summarize the method bias results.

Analyzing the above data, acceptable rWG results were found, excluding one result (highlighted in bold).

Analyzing the data above, acceptable tolerance (tolerance > 0.1) and VIF (VIF < 10) results were detected for all populations.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to explore key drivers in service delivery and individuals involved, by presenting a multi-level approach for exploring and measuring individual, dyadic and organizational drivers all in order to enhance service delivery outcomes. Specifically, hypotheses were set forward in order to address the question of whether actionable trust is a predictable construct that is influenced by individual drivers (competencies), dyadic drivers (trust) and organizational drivers (values).

Organizations in general, and more specifically service organizations in the higher education industry, face an increasing struggle in the strong and demanding marketplace. In today's knowledge-based economic system, it is well known that higher education is the foundation of fostering high-potential talent, the key factor in raising national and international quality, and the main way to upgrade national competitive ability (Chen & Chen, 2011). As a result, today, when higher education institutions are required with managerial efficiency, economic benefits, and international competitiveness, institutional performance-based accountability has been and continues to be a major factor affecting higher education funding and planning (Wu, Tsai, & Hung, 2012).

One interesting finding is the negative correlation detected between the client's age and actionable trust. The study found that younger individuals tend to have a higher actionable trust score. From an organizational perspective, and while sometimes overlooked, this emphasizes that service organizations might benefit from a "younger " population, since the chances for actionable trusting behaviors might increase. These findings may be explained by the Social Identity Theory (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Tajfel & Turner, 1985). The Social Identity Theory was originally developed in order to understand the psychological basis of intergroup discrimination. Tajfel and Turner (1985) attempted to identify the minimal conditions that would lead members of one group to discriminate in favor of the "in-group" to which they belonged and against another "out-group". This yields that people prefer interacting with similar individuals. Moreover, this similarity might yield similar judgment. Thus, exa mining these results in light of the organizational circumstances within the higher education sector, we claim that the social identity need of young individuals who demonstrated trust, i.e., provided and actual recommendation to others, positively interact with their group mates (peer students or peer service providers) and increases the chance for organizational success (Roberts-Lombard & Du Plessis, 2012).

We hypothesized that a high level of dyadic contribution throughout the service delivery process results in actionable trust (Hypo thesis 2). As expected, trust as a belief and procedural justice have an impact on actionable trust. Our results prove a robust signaling process and strong reciprocity foundations within the specific organizational context (Johns, 2006). Most clients perceive the relationship to be a social exchange (Blau, 1964; Chalutz Ben-Gal & Tzafrir, 2011). At times, the relationship spills over from a pure social exchange to a "family-like" relationship, therefore resulting in high levels of actionable trust. This emotional state may shed light on the intensity of the exchange process within the organization, as well as on the high reciprocity level, therefore being able to explain the connection between trust and actionable trust.

Our following step in the study is to explore commonalities between service providers and clients as well as amongst themselves. Therefore, we hypothesized that high level of fit in values between clients and service providers throughout the service delivery process will result in high levels of actionable trust (Hypothesis 3). Study results indicate that high levels of fit in the perception of organizational values between client and service providers results in high levels of actionable trust.

Why is this so? We highlight the Pareto Principle (Keeley, 1984), which claimed that 80 percent of organizational phenomena may be explained by 20 percent of resources. Therefore, we focused on six out of the twenty-two organizational values which were rated by external judges as being the "heart and soul" of the desired organizational culture. These six values were rated to be: Personal Initiative, Authority Delegation, Cooperation, Change and Dynamics, Labor Relations, and Employee Satisfaction. Though study results indicate that there are variations in fit level between these six values and their impact on actionable trust, a general positive connection was detected.

The first possible explanation to the study results is based on The Stakeholder Theory. Similarly to an organizational downsizing scenario (Tzafrir et al., 2012), a complex service delivery process also puts an emphasis on the central role of values. Within this context, values play an important role. Service providers, as well as clients, enter the service delivery process with stable values and conceive notions of what 'ought' and what 'ought not' to be (Ibid, p. 401). Thus, the interactions between actors in this process "lay the foundation for an understanding of other actors' behavior and attitudes, as well as influencing them. Thus, values help us to predict, interpret, and act accordingly, in order to achieve better performance" (Ibid, p. 402).

Our results can back-up a "Management by Fit" approach. In service organizations, where multiple stakeholders exist, the challenge of aligning values is even more complex. Key stakeholders - clients, service providers, employees, and others - need to get a clear understanding of which values and beliefs are to be aligned, as well as how to go about the process of adaptation in a successful manner. In line with O'Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell, (1991) the closer the fit, the lower the conflict inherent in the particular situation (high-quality service delivery, for example). On the other hand, the better the fit in values between stakeholders, the higher the probability of a high level of actionable trust which may lead to organizational success.

Practical and Theoretical Implications

This study sheds light on some practical and theoretical issues detailed hereafter.

First, the study presents organizations with a management tool for managing actionable trust.

Second, it emphasizes key theoretical drivers - individual, dyadic and organizational - that trigger actionable trust and differ it from intentions of trust.

Third, the emphasis put on the importance of actionable trust in the workplace in general, and more specifically in service organizations, a setting in which clients are key, may lead organizations to invest in trust-building strategies and interventions. Such activities and interventions focus on important relational aspects that may improve interactions and their effectiveness within the organization. In service organizations context, such interventions may focus on personality identification of service providers in order to maximize service delivery and as a result gain client's trust (Simsarian et al., 2012). This may assist organizations in building and sustaining a trusting atmosphere and better organizational outcomes. Some of these interventions result in higher trust levels, and as a result higher ratings of service quality on behalf of clients. Therefore, hiring and developing employees that are predisposed to manage actionable trusting activities may facilitate the success of the service organization.

Fourth, our research provides evidence for Human Resources and General Managers regarding the importance of actionable trust. By suggesting this, managers may understand the importance of trust building organizational activities on the individual, dyadic, and organizational levels, thus investing adequate organizational resources accordingly.

Future Research

This research might benefit from advancing in some optional future directions. Therefore, future research might benefit from addressing three key factors. First, an interesting factor to incorporate in future measurement process includes the examination of environmental factors by adding a SWOT analysis (Humphrey, 1974). The SWOT analysis maps the organizations Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats and incorporating them into the individual -dyadic-organizational framework. This research direction might add an important external perspective.

Second, an alternative additional research might be to zoom into one of the levels of analysis presented in this study - individual, dyadic, or organizational. The purpose would be to perform an in-depth one-dimensional longitudinal analysis of the research variables, in order to examine its effect on actionable trust. An interesting question to ask in this case would be, does actionable trust measurement change? If yes, why? How does this influence trust as an intention, if at all?

Limitations

Despite its importance, this study is, however, subject to a number of limitations.

First, it may well be the case that the study suffered from a social desirability bias. Since most of our client respondents were students in the same organization, and despite the anonymous process, at times people were filling questionnaires in huge and crowded classrooms, therefore potentially influencing study results. Nonetheless, this problem might be virtually non-existent because results of all measurement were intertwined and supported each other.

Second, the study may have suffered a mono-method bias. Our model presents a multi-level approach of service delivery drivers - competencies (individual level), trust (dyadic level) and values (organizational level) - as a conceptual platform which influences actionable trust. From a practical point of view, this study contributes a straightforward management tool for measuring the effectiveness of their service delivery process. It emphasizes key drivers, dyadic and organizational, that are key success factors and are critical in service settings and therefore provides a framework for evaluating and measuring these key success factors within an organizational context. Our suggested multi-level framework enabled us to grasp a wider point of view that includes the micro level as well as macro level challenges that service organizations face. On the dyadic level, we explore the need to give attention to the relational aspect of service delivery (Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2012). On the macro level, we focused on value fit amongst clients and service providers, which is crucial in order to achieve common organizational grounds, especially when multiple stakeholders are involved (Malvey, Fottler, & Slovensky, 2012). Such better fit (Edwards & Cable, 2004; Edwards & Cable, 2009; Nadler & Tushman, 1980) between parties focuses on how closely personal values match the organizational values.

The basic assumption is that the closer the fit, the lower the conflict inherent in the particular situation.

Third, taking into account the fit concept, our calculation of the fit score and congruence might have suffered methodologically. Fit and congruence definitions have evolved over the years to achieve significant progress (Cable & Edwards, 2004; Edwards & Cable, 2009; Nadler & Tushman, 1980). Based on previous research, Cable and Edwards (2004) claim that according to the person-environment fit paradigm, attitudes and behaviors result from the congruence between attributes of the person and the environment. Their continuing research of the fit concept (Edwards and Cable, 2009) suggests that "when employees hold values that match the values of their employing organization, they are satisfied with their jobs, identify with the organization, and seek to maintain the employment relationship" (p. 654). These researchers based their fit measurement using a cross-sectional sample. However, in this study's procedure, in order to limit the mono-method bias effect, we measured fit using two sources in separate time periods (including a continuing study). This was done for the purpose of measuring two distinct populations - one internal to the organization (service providers) and the other external to the organization (clients). Moreover, we compared these two sources in order to gain a wider perspective.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

1Some studies of the higher education sector (Alam et al., 2010; Arambewela, 2006; Chen & Chen, 2011) suggest that utilizing diverse measurement tools might shed light on service quality and organizational performance.

2Measuring values within the organizational context imposed some meaningful challenges. First, the complexity of a service delivery setting (Lytle, Hom, & Mokwa, 1998; Ros, et al., 1999) led us to the understanding that values are to be measured from a wide perspective of all stakeholders involved, service providers, as well as clients (Malvey et al., 2002). Second, we accepted the need to measure value fit between service providers and clients.

3Fit score was calculated by generating a "fit index" as follows: 1) absolute difference between client rating and service provider rating of value was calculated. 2) Results per value were subtracted from the highest score of 5 reflecting anomality in high/low ratings of value (Edwards, 2001).

References

1. Ajzen, I., & Madden, T. J. (1986). Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 453-474. [ Links ]

2. Alter, C., & Hage, J. (1993). Organizations Working together. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

3. Armenakis, A. A., & Harris, S. G. (2009). Reflections: our journey in organizational change research and practice. Journal of Change Management, 9, 127-142. [ Links ]

4. Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20-39. [ Links ]

5. Asing-Cashman, J. G., Gurung, B., Limbu, Y. B., & Rutledge, D. (2014). Free and Open Source Tools (FOSTs): An Empirical Investigation of Pre-Service Teachers' Competencies, Attitudes, and Pedagogical Intentions. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 26, 66-77. [ Links ]

6. Auster, E. R., & Freeman, R. E. (2013). Values and poetic organizations: Beyond value fit toward values through conversation. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 39-49. [ Links ]

7. Baruch, Y., & Holtom, B. C. (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61, 1139-1160. [ Links ]

8. Berry, L. L. (2002). Relationship marketing of services perspectives from 1983 and 2000. Journal of relationship marketing, 1, 59-77. [ Links ]

9. Bettencourt, L. A., Gwinner, K. P., & Meuter, M. L. (2001). A comparison of attitude, personality and knowledge predictors of service - oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 29-41. [ Links ]

10. Bijslma-Frankema, K., De Jong B., & Van de Bunt G. (2008), Heed, a missing link between trust, monitoring and performance in knowledge intensive teams. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19, 19-40. [ Links ]

11. Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

12. Bromiley, P, & Cummings, L. L. (1996). The Organizational Trust Inventory (OTI): Development and Validation. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: International Educational and Professional Publisher, Sage Publications. [ Links ]

13. Brower, H. H., Lester, S. W., Korsgaard, M. A., & Dineen, B. R. (2009). A closer look at trust between managers and subordinates: Understanding the effects of both trusting and being trusted on subordinate outcomes. Journal of Management OnlineFirst. [ Links ]

14. Brown, S. P., & Lam, S. K. (2008). A meta-analysis of relationships linking employee satisfaction to customer responses. Journal of Retailing, 84, 243-255. [ Links ]

15. Butler, J. K. (1991). Toward understanding and measuring conditions of trust: evolution of a condition of trust inventory. Journal of Management, 17, 643-663. [ Links ]

16. Cable, D. M., & Edwards, J. R. (2004). Complementary and supplementary fit: a theoretical and empirical integration. Journal of applied psychology, 89, 822-834. [ Links ]

17. Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (1999). Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Series in Organizational Development. [ Links ]

18. Chalutz Ben-Gal, H., & Tzafrir, S. S. (2011). Consultant-Client Relationship: one of the secrets to effective organizational change? Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24, 662-679. [ Links ]

19. Chandon, J. L., Leo, P. Y., & Philippe, J. (1997). Service encounter dimensions-a dyadic perspective: Measuring the dimensions of service encounters as perceived by customers and personnel. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8, 65-86. [ Links ]

20. Chen, J.-K., & Chen, J.-S., (2011). Inno-qual efficiency of higher education: empirical testing using data envelopment analysis. Expert Systems with Applications, 38, 1823-1834. [ Links ]

21. Chuang, C. H., & Liao, H. U. I. (2010). Strategic human resource management in service context: Taking care of business by taking care of employees and customers. Personnel Psychology, 63, 153-196. [ Links ]

22. Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425-445. [ Links ]

23. Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Rodell, J. B., Long, D. M., Zapata, C. P., Conlon, D. E., & Wesson, M. J. (2013). Justice at the millennium, a decade later: a meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 199-236. 28. [ Links ]

24. Coulter, R. A., & Ligas, M. (2004). A typology of customer-service provider relationship: the role of relational factors in classifying customers. The Journal of Services Marketing, 18, 482-493. [ Links ]

25. Curral, S. C., & Judge, T. A. (1995). Measuring trust between organizational boundary role persons. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64, 151-170. [ Links ]

26. Czarniawska, B., & Mazza, C. (2003). Consulting as Liminal Space. Human Relations, 53, 267-290. [ Links ]

27. Devos, T., Spini, D., & Schwartz, S. H. (2002). Conflicts among human values and trust and institutions. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 481-494. [ Links ]

28. Dietz, G., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2006). Measuring Trust Inside Organizations. Personnel Review, 35, 567-588. [ Links ]

29. Dolan, S. L., & Garcia, S. (2002). Managing by values: cultural redesign for strategic organizational change at the dawn of the twenty-first century. The Journal of Management Development, 21, 101-117. [ Links ]

30. Donovan, M. A., Drasgow, F., & Probst, T. H. (2000). Does computerizing paper-and-pencil job attitude scales make a difference? New IRT analyses offer insight. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 305-313. [ Links ]

31. Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2009). The value of value congruence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 654-677. [ Links ]

32. Eisenberger, R., Hungtington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500-507. [ Links ]

33. Fichman, M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1991). Honeymoons and the liability of adolescence: a new perspective on duration dependence in social and organizational relationships. Academy of Management Review, 16, 442-468. [ Links ]

34. Fricker, S., Galesic, M., Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2005). An experimental comparison of web and telephone surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69, 370-392. [ Links ]

35. Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161-179. [ Links ]

36. Gutek, B. A., Bhappu, A.D., Liao-Troth, M. A., & Cherry, B. (1999). Distinguishing Between Service Relationships and Encounters. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 218-233. [ Links ]

37. Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Wheeler, A. R. (2012). To invest or not? The role of coworker support and trust in daily reciprocal gain spirals of helping behavior. Journal of Management (Published online before print). [ Links ]

38. Harris, L. C., & Goode, M. M. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: a study of online service dynamics. Journal of retailing, 80, 139-158. [ Links ]

39. Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-Unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 268-279. [ Links ]

40. Hempel, P. S., Zhang, Z-X., & Tjosvold, D. (2009). Conflict management between and within teams for trusting relationships and performance in China. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 41-65. [ Links ]

41. Herscovitch, L., & Meyer, J. P. (2002). Commitment to organizational change: extension of a three-component model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 474-487. [ Links ]

42. Hitt, M. A., Bierman, L., & Shimizu, K. (2001). Direct and moderating effects of human capital on strategy and performance in professional service firms: a resource-based perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 13-28. [ Links ]

43. Hollenbeck, J. R., Williams, C. R., & Klein, H. J. (2001). An empirical examination of the antecedents of commitment to difficult goals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 18-23. [ Links ]

44. Humphrey, A. S. (1974). MBO Turned Upside Down. Management Review, 63(8), 4-8. [ Links ]

45. Jarillo, J. C. (1988). On Strategic Networks. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 31-41. [ Links ]

46. Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31, 386-408. [ Links ]

47. Johnson, D., & Grayson, K. (2005). Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. Journal of Business Research, 58, 500-507. [ Links ]

48. Kandampully, J.(2002). Innovation as the core competency of service organizations: the role of technology, knowledge and networks. European Journal of Innovation Management, 5, 18-28. [ Links ]

49. Kantsperger, R., & Kutz, W. H. (2010). Consumer trust in service companies: a multiple mediating analysis. Managing Service Quality, 20, 4-25. [ Links ]

50. Keeley, M. (1984). Impartiality and participant-interest theories of organizational effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29, 1-25. [ Links ]

51. Konovsky, M. A., & Pugh, S. D. (1994). Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 656-669. [ Links ]

52. Korsgaard, M. A., Brower, H. H., & Lester, S. W. (2015). It Isn't Always Mutual A Critical Review of Dyadic Trust. Journal of Management, 41, 47-70. [ Links ]

53. Laroche, M., Ueltschy, L. C., Abe, S., Cleveland, M., & Yannopoulos, P. P. (2004). Service quality perceptions and customer satisfaction: evaluating the role of culture. Journal of International Marketing, 12(3), 58-85. [ Links ]

54. Lawler, E. E. (1993, July). From job-based to competency-based organizations (Working Paper). The Center for Effective Organizations, The Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California. [ Links ]

55. Lepak, D. P., & Snell, S. A. (1999). The human resource architecture: toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. Academy of Management Review, 24, 31-48. [ Links ]

56. Liao, H., Toya, K., Lepak, D. P., & Hong, Y. (2009). Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 371-391. [ Links ]

57. Liao, C.-H., Yen, H. R., & Li, E. Y. (2011). The effect of channel quality inconsistency on the association between e-service quality and customer relationships. Internet Research, 21, 458-478. [ Links ]

58. Lytle, R. S., Hom, P. W., & Mokwa, M. P. (1998). SERV*OR: A managerial measure of organizational service orientation. Journal of Retailing, 74, 455-489. [ Links ]

59. Mach, M., Dolan, S., & Tzafrir, S., (2010). The differential effect of team members' trust on team performance: The mediation role of team cohesion. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 771-794. [ Links ]

60. Malvey, D., Fottler, M. D., & Slovensky, D. J. (2002). Evaluating stakeholder management performance using a stakeholder report card: the next step in theory and practice. Health Care Management Review, 27, 66-79. [ Links ]

61. Mayer, R. C., Davis, J., H., & Schoorman, F., D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709-734. [ Links ]

62. downsizing strategies. Human Resources Management, 33, 261-279. [ Links ]

63. McAllister, D. J. (1995), Affect and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 24-59. [ Links ]

64. Menguc, B. (2000). An empirical investigation of a social exchange model of organizational citizenship behaviors across two sales situations: A Turkish Case. The Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 20, 205 32. [ Links ]

65. Mishra, A. (1996). Organizational responses to crisis: The centrality of trust. In R. M. Kramer & T. Tyler (eds.), Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

66. Mishra, A. K., & Mishra, K. E. (1994). The role of mutual trust in effective downsizing strategies. Human Resources Management, 33, 261-279. [ Links ]

67. Nadler, D. A., & Tushman, M. L. (1980). A model for diagnosing organizational behavior. Organizational Dynamics, 9, 35-51. [ Links ]

68. Noor, K. B. M. (2008). Case study: A strategic research methodology. American Journal of Applied Science, 5, 1602-1604. [ Links ]

69. O'Reilley, C. A., Chatman, J., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: a profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487-516. [ Links ]

70. Park, J., Lee, J., Lee, H., & Truex, D. (2012). Exploring the impact of communication effectiveness on service quality, trust and relationship commitment in IT services. International Journal of Information Management, 32, 459-468. [ Links ]

71. Reynolds, K. E., & Beatty, S. E. (1999). A relationship customers typology, Journal of Retailing, 75, 509-523. [ Links ]

72. Roberts-Lombard, M., & Du Plessis, L. (2012). Customer relationship management (CRM) in a South African service environment: an exploratory study. African Journal of Marketing Management, 4(4), 152-165. [ Links ]

73. Russo, A., & Perrini, F. (2010). Investigating Stakeholder Theory and social capital: CSR in large firms and SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 91, 207-221. [ Links ]

74. Rust, R. T., & Huang, M. H. (2012). Optimizing service productivity. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 47-66. [ Links ]

75. Savage, G. T., & Bunn, M. D. (2010). Stakeholder collaboration: implications for stakeholder theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 96, 21-26. [ Links ]

76. Schwartz, S. H., & Rubel, T. (2005). Sex differences in value priorities: cross-cultural and multi-method studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 1010-1028. [ Links ]

77. Simsarian Webber, S., Payne, S. C., & Taylor, A. B. (2012). Personality and trust fosters service quality. Journal of Business Psychology, 27, 193-203. [ Links ]

78. Six, F. E. (2007). Building interpersonal trust within organizations: a relational signaling perspective, Journal Manage Governance, 11, 285-309. [ Links ]

79. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1985). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.). Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 7-24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall. [ Links ]

80. Tepper, B. J., Lambert, L. S., Henle, C. A., Giacolone, R. A., & Duffy, M. K. (2008). Abusive supervision and subordinates' organization deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 721-732. [ Links ]

81. Tzafrir, S. S., Chalutz Ben-Gal, H., & Dolan, S. L. (2012). Exploring the etiology of positive stakeholder behavior in global downsizing. In C. L. Cooper, A. Pandey A., & J. C. Quick (Eds.), Downsizing - Is less still more? (chapter 13, pp. 389-417). Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

82. Tzafrir, S. S., & Dolan, S. L. (2004). Trust Me - A Scale for Measuring Manager - Employee Trust. Management Research, 2, 115-132. [ Links ]

83. Van Buren III, H. J., & Greenwood, M. (2011). Bringing Stakeholder Theory to Industrial Relations. Employee Relations, 33, 5-21. [ Links ]

84. Van Quaquebeke, N., Graf, M. M., Kerschreiter, R., Schuh, S. C., & Dick, R. (2014). Ideal Values and Counterideal Values as Two Distinct Forces: Exploring a Gap in Organizational Value Research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16, 211-225. [ Links ]

85. Verbeke, A., & Tung, V. (2012). The Future of stakeholder management theory: a temporal perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 10, 1276-1291. [ Links ]

86. Webber, S. S., & Payne, S. C. (2012). Personality and trust fosters service quality, Journal of Business Psychology, 27, 193-203. [ Links ]

87. Williamson, O. E. (1993). Contested exchange versus the governance of contractual relations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7, 103-108. [ Links ]

88. Wu, S. H., Tsai, C. Y. D., & Hung, C. C. (2012). Toward team or player? How trust, vicarious achievement motive, and identification affect fan loyalty. Journal of Sport Management, 26, 177-191. [ Links ]

89. Zaheer, A., McEvily, & B. Perrone, V. (1998). Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organizational Science, 9, 141-159. [ Links ]

90. Zand, E. D. (1972). Trust and managerial problem solving. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, 229-239. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Hila Chalutz Ben-Gal, PhD.

Afeka Tel Aviv Academic College of Engineering.

Industrial Engineering and Management Department.

38 Mivtza Kadesh St. Tel Aviv.

6998812 ISRAEL.

E-mail: hilab@afeka.ac.il

Manuscript received: 13/04/2014

Revision received: 29/10/2014

Accepted: 02/02/2015