Human resources are valuable intangible assets in the organisation. Their needs and desires are diverse, and difficult to understand. Due to increasing size of the industry and the complexity associated with its operations and human element, many organisations have been implementing mentoring programmes. Mentoring helps in increasing the morale of the employees and motivates them to achieve organisational goals. Through mentoring, organisations see their employees more personally and obtain knowledge about their personal as well as work related needs. It is just like a thread that integrates individual and organisational-based goals. Organisations can attain manifold benefits from mentoring their employees (Allen, Eby, Poteet, Lentz, & Lima, 2004; Ismail et al., 2009; Ismail & Ridzwan, 2012; Washington, 2011). These gains are further strengthened through the presence of a mentoring culture and a mentoring structure in the organisation (Jyoti & Sharma, 2015a). There are certain employee characteristics, like self-efficacy (Pan, Sun, & Chow, 2011) and mentor's willingness, that can also boost mentoring outcomes (Ismail & Ridzwan, 2012). Various types of mentoring programmes exist in organisations, like formal and informal mentoring programmes. Formal mentoring programmes are deliberate action plans implemented by the organisation. In this programme, organisation appoints mentors, who guide, protect, coach, and counsel mentees/employees, whereas in the informal mentoring relations develop on their own (Hansman, 2000), i.e., a person approaches a favoured person (mentor) and that person agrees to form a mentoring relationship. It develops through mutual interaction or attraction (Hu, Wang, Wang, Chen, & Jiang, 2016). Ragins and Cotton (1999) explored formal as well as informal mentoring relationships and revealed that protégés with informal mentors receive greater benefits than protégés with formal mentors. Protégés with informal mentors experience more career development and psychosocial functions than protégés with formal mentors. They also found that protégés with informal mentors are more satisfied with their mentors than protégés with formal mentors. Ragins, Cotton, and Miller (2000) also examined mentoring in both formal and informal environment. They compared career and job attitudes among individuals with formal mentors and informal mentors and found that satisfaction with a mentoring relationship had a stronger impact on attitudes, irrespective of the type of relationship, i.e., formal or informal.

Earlier conceptual and empirical research papers have revealed that mentoring results in job satisfaction (Lo, Thurasamy, & Liew, 2014). In a mentoring relationship the mentor helps the mentee understand his/her job roles and responsibilities, which removes job ambiguity and role ambiguity to a great extent (Lankau & Scandura, 2002), which in turn enhances employees’ job satisfaction (Jyoti & Sharma, 2015a; Lo, Ramayah, & Kui, 2013). The mentor provides career functions and psychosocial functions, and acts as a role model to continuously encourage the mentee to exhibit his/her best talent that motivates him/her to achieve personal as well as organisation goals (Akarak & Ussahawanitchakit, 2008; Emmerik, 2008; Lo et al., 2013). Further, coaching and counselling provided by the mentor with regard to different aspects of job as well as the organisation help to develop loyalty components among the mentees that results in organisational commitment (Ghosh & Reio, 2013), low turnover (Chen, Liao, & Wen, 2014; Payne & Huffman, 2005), emotional sharing (Liu, Jun, & Weitz, 2011), employee satisfaction and perceived career success (Lester, Hannah, Harms, Vogelgesang, & Avolio 2011; Murphy & Ensher, 2001), etc.

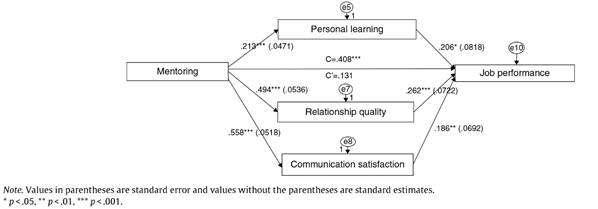

Research has also been conducted on formal and informal mentoring (Chen et al., 2014; Emmerik, 2008; Germain, 2011; Okurame, 2008; Ragins et al., 2000; Ramaswami, Huang, & Dreher 2014; Washington, 2011) and on gender and race differences in mentoring (Lo et al., 2013; Ramaswami et al., 2014; Vries, Webb, & Eveline, 2006). Earlier studies have also recommended exploration of the moderating and mediating variables between mentoring and its outcomes (DuBois, Holloway, Valentin, & Cooper, 2002; Godshalk & Sosik, 2000; Jyoti & Sharma, 2015b). Previous researchers have revealed a positive impact of mentoring on quality of relationship (Lakind, Atkins, & Eddy, 2015; Langhout, Rhodes, & Osborne, 2004; Sandner, 2015), communication satisfaction (Madlock & Lightsey, 2010; Rowland, 2012), and personal learning (Lankau & Scandura, 2002; Pan et al., 2011). Further, Schunk and Mullen (2013) conceptualised that an integration of mentoring with self-regulated learning gives desired results, i.e., academic motivation, achievement, long-term productivity, and retention of individuals in the profession. Pan et al. (2011) proved that self-efficacy moderates the relationship between mentoring and personal learning and suggested exploring this subordinate characteristic, i.e., self efficacy, between mentoring and related outcomes. Jyoti and Sharma (2015a, 2015b) proved that organisational characteristics like mentoring structure and mentoring culture strengthen the relationship between mentoring and career development, and mentoring and job satisfaction. Authors have revealed that personal characteristics such as proactive personality (Wang, Hu, Hurst, & Yang, 2014), core self-evaluation (Wu, Zhuang, & Hung, 2014), and emotional intelligence (Hu et al., 2016) moderate the relationship between mentoring and its related outcomes. Taking clue from this, we generated the theoretical framework wherein self-efficacy moderates between mentoring and relationship quality, mentoring and communication, and mentoring and personal learning. Additionally, researchers have pointed that the impact of mentoring on mentees’ attitude is not direct but it is mediated through various other mechanisms and hinted at the need to explore the mediating variables (Lankau & Scandura, 2002; Liu et al., 2011; Madlock & Lightsey, 2010). Pan et al. (2011) suggested mentoring quality should be explored between mentoring and job performance. Further, Ragins et al. (2000) suggested that future research should focus on more in-depth examination of the quality of mentoring relationships. Therefore, the present research focuses on the evaluation of the mediating role of personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction between mentoring and job performance (this is presented diagrammatically in Figure 1). Further, the integrated model (moderated-mediation) about the overall impact of moderating and mediation variables between mentoring and job performance has not been evaluated earlier. This can help to reveal a clear picture of the impact of mentoring on job performance (Table 1). Thus, the focus of present research is on the mediated effect of personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction between the interaction effect of mentoring and self-efficacy on job performance.

Table 1 Moderation and Mediation Studies in Mentoring Context.

| S. No. | Authors | Outcome Variables | Moderator | Mediator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lankau and Scandura (2002) | Role ambiguity, job satisfaction and intention to leave | ------------ | Personal learning |

| 2 | Day and Allen (2004) | Career success | Career motivation and career self-efficacy | |

| 3 | Rhodes, Reddy, and Grossman (2005) | Substance use in adolescence | Parent relations | |

| 4 | Poon (2006) (conceptual) | Mentoring relationship, personal and professional development | -------------- | Mentee's and mentor's self-efficacy |

| 5 | Byrne et al. (2008) | Career success (job interpersonal, financial, hierarchical), in-role job performance, career satisfaction and organisational career satisfaction. | Proactive personality, career motivation and career stage | Career self-efficacy |

| 6 | Ismail and Jui (2009) | Individuals psychosocial behaviour | Gender type (same gender, cross gender) | |

| 7 | Ismail et al. (2009) | Individual career development | Gender difference | |

| 8 | Madlock and Lightsey (2010) | Job satisfaction and organisational commitment | ----------------- | Communication satisfaction |

| 9 | Fleig-Palmer and Schoorman (2011) | Knowledge transfer | Trust | |

| 10 | Pan et al. (2011) | Job performance and career satisfaction | Self-efficacy | Personal learning |

| 11 | Ismail and Ridzwan (2012) | Individual psychosocial behavior | ------------ | Same gender |

| 12 | Lo et al. (2013) | Job satisfaction | Supervisor gender | |

| 13 | Chan et al. (2013) | Misconduct, prosocial behaviour, academic attitude, self-esteem and academic performance(grade) | ------------- | Parent relationship, teacher relationship and mentor relationship |

| 14 | Kao et al. (2014) | Mentoring relationship | Gender | |

| 15 | Kwan, Yim, and Zhou (2014) | Employees’ customer orientation | Gender | |

| 16 | Qian, Lin, Han, Chen, and Hays (2014) | Job-related stress | Protégés’ individual traditionality and trust in mentor | |

| 17 | Collings, Swanson, and Watkins (2014) | Intention to leave | Integration into the new environment | |

| 18 | Sun, Pan, and Chow (2014) | Contextual performance and promotability | ------------- | - Psychological empowerment - Organisation based self-esteem - Supervisor political skill |

| 19 | Chen et al. (2014) | Affective commitment and turnover intentions | Power distance orientation | Psychological safety |

| 20 | Michelle and Chery (2015) | knowledge transfer and retention relationship | affective commitment | |

| 21 | Arora and Rangnekar (2015) | Organisational commitment | Agreeableness and conscientiousness | |

| 22 | St-Jean and Mathieu (2015) | Job satisfaction and intention to stay | --------- | Entrepreneurial self-efficacy |

| 23 | Jyoti and Sharma (2015b)) | Career development | Mentoring culture and mentoring structure | |

| 24 | Park, Newman, Zhang, Wu, and Hooke (2015) | Turnover intention | Perceived organisational support |

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Moderation Hypotheses

There are studies which have proved career self-efficacy as a mediator between mentoring and career success (Day & Allen, 2004). Further, St-Jean and Mathieu (2015) evaluated entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a mediator between mentoring and job satisfaction as well as intention to stay, but DiRenzon, Linnehan, Shao, and Rosenberg (2010), Huang and Weng (2011), Pan et al. (2011), and Park and Lee (2012) all empirically proved that employees’ self-efficacy moderates the relationship between mentoring and personal learning. Taking clue from this, we have generated the following hypotheses.

Self-efficacy, mentoring, and personal learning. Self-efficacy is defined as the personal judgement about one's capability to adopt certain behaviours and actions in order to accomplish certain objectives and expected outcomes (Pan et al., 2011; Wu, Lee, & Tsai, 2012). It has an impact on an individual's emotional reactions and thought patterns (Cherian & Jacob, 2013). Researchers have proven that self-efficacy influences self-control, performance, task efforts (Bandura, 1986), effective problem resolving (Gist & Mitchell, 1992), feelings of stress and anxiety (Prussia, Anderson, & Manz, 1998), coping behaviour, individual choice behaviour, effort to overcome obstacles (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998), organisational commitment (Vuuren, DeJong, & Seydel 2008), etc.

According to the mentoring theory, a mentor can provide a protégé with functions such as guidance, role modelling, and acceptance (Day & Allen, 2004). These functions are directly associated with the individual's sense of ability and self-efficacy (Goh, Ogan, Ahuja, Herring, & Robinson, 2007), because a person cannot learn from a mentoring programme until and unless his/her self-urge encourages him/her to do so. Mentees’ level of self-confidence, capability, and competence (indicator of self-efficacy) enhances the relationship between supervisory mentoring and personal learning. DiRenzon et al. (2010), Huang and Weng (2011), Pan et al. (2011), and Park and Lee (2012) stated that self-efficacy moderates the relationship between the mentoring function and adaptation to learning. An individuals’ perceived self-efficacy is an important factor in determining behavioural performances. Further, the higher the faith the protégés have in them, the higher their capacity to learn during the mentoring relationship. Therefore, self-efficacy boosts the relationship between mentoring and personal learning.

Hypothesis 1a: Mentee's self-efficacy moderates the relationship between mentoring and personal learning.

Self-efficacy, mentoring, and relationship quality. Effective mentoring helps to establish a healthy relationship between mentor and mentee (Kao, Rogers, Spitzmueller, Lin, & Lin, 2014; Sosik & Godshalk, 2005; Xu & Payne, 2014) and depends upon the amount of effort exerted by both the mentor and mentee for the sustainability of the relationship (Parra, Dubois, Neville, & Pugh-Lilly, 2002). Experienced support from a mentor has been revealed to result in personal as well as professional knowledge development, feedback, reciprocity of the relationship, friendliness, and trust. These indicators help in building sound mentor-mentee relationship (Lofstrom & Eisenschmidt, 2009). Skinner and Belmont (1993) found that the relationship quality depends upon feedback and the number of interactions that mentor and mentee experience over a period of time. This relationship is improved when mentoring is integrated with self-efficacy, and when efficacious mentee performs the task as per the mentor's expectations it helps to create a positive image in front of mentor, brings them close to each other, and helps to boost the relationship between mentor and mentee. Efficient employees/mentees absorb the guidance provided by the mentor very quickly (Higgins & Thomas, 2001), which makes the mentor feel a sense of accomplishment and take initiative to develop better relationship in terms of quality time allocation, interactions, and informal get together. Therefore, success in mentoring in business is boosted when an employee is confident and performs the job efficaciously (Byrne, Dik & Chiaburu, 2008; Day & Allen, 2004), which in turn helps to establish a healthy relationship between the persons involved in this programme.

Hypothesis 1b: Mentee's self-efficacy moderates the relationship between mentoring and the quality of relationship.

Self-efficacy, mentoring, and communication satisfaction. Madlock and Lightsey (2010), and Lasater et al. (2014) found a positive relationship between supervisor's mentoring and subordinate's communication satisfaction. In mentoring, mentees with high self-efficacy tend to be actively involved in development and learning activity, thus they are more likely to engage in and benefit more from a mentoring relationship (Allen et al., 2004; Pan et al., 2011). Efficacious employees are confident and able to communicate their point of view to their mentor and in turn understand their mentor's point of view too, which helps in the free flow of communication of information, learning from each other, and exchange of growth opportunities, which in turn helps to establish communication satisfaction. Mentors also communicate their ideas, challenges, and career opportunities available to efficacious employees/mentees more than to the less efficacious ones as they know that efficacious employees/mentees have a higher level of confidence to do the job. So, the mentor communicates more with them, listens, and pays more attention to such mentees, which instils a feeling of communication satisfaction among mentees. Thus, the key factor, which strengthens mentoring and communication satisfaction, is the level of mentee's self-efficacy. DiRenzon et al. (2010) stated that self-efficacy buffers the effect of mentoring related outcomes.

Hypothesis 1c: Mentee's self-efficacy moderates the relationship between mentoring and communication satisfaction.

Mediation Hypotheses

Mentoring, personal learning, relationship quality, communication satisfaction, and job performance. One of the important work relationships that can serve as a platform for personal learning is mentoring (Butterworth, Henderson, & Minshell, 2008; Janasz & Godshalk, 2013; Lankau & Scandura, 2002). Individuals learn a great deal through their interactions with others, especially those with different backgrounds, expertise, and experience in the organisation. Mentoring mechanisms/functions enhance personal learning of mentees (Rueywei, Shih-Ying, & Min-Lang 2014; Schunk & Mullen, 2013) by providing knowledgeable feedback (Lofstrom & Eisenschmidt, 2009) about various activities, which in turn improve mentees’ job performance (Anseel, Beatty, Shen, Lievens, & Sackett, 2015). Positive mentoring makes a mentee feel safe to ask questions, take challenging assignments, and in return mentor actively listens and welcomes mentee's to discuss various work related problems, which helps increase mentee's learning capabilities (Lankau & Scandura, 2002). This increase in the learning capability and changes in behaviours makes a mentee do his/her job in a better way (Kram, 1985). Further, Pan et al. (2011) examined the mediating role of personal learning between supervisory mentoring and career outcomes. Mentoring can influence a protégé’s behavioural (personal learning) reactions towards the workplace. This behaviour is associated with a more positive job experience (performance). Further, Kram and Hall (1996) revealed that mentors are a valuable resource for learning organisations, and mentoring (vocational support) is positively related to personal learning. The mentoring support provided by a mentor helps the protégé increase his/her understanding of the job context through learning skill, which may result in less confusion about the expectations associated with their roles in the organisation. It permits the mentee to improve his/her competencies that are related to his/her job performance (Hezlett, 2005). Liu, Liu, Kwan, and Mao (2009) found that mentoring is positively related to mentee's personal learning that in turn positively affects mentee's job performance.

Further, mentoring is an association between two people built upon trust, in which the mentor offers ongoing support and development opportunities to the mentee (Clutterbuck, 2004). Both share a common purpose of continuous development and growth, which help build the quality of relationship. It has been found that those individuals who experienced high quality relationship (as defined by measures of closeness, satisfaction, and engagement in their relationships) derived more benefits than those who experience lower quality relationships (Chan et al., 2013; Schwartz, Rhodes, Chan, & Herrera, 2011). Mentoring enhances relationship quality (Hu et al., 2016; Lakind et al., 2015; Sandner, 2015). A healthy relationship increases the frequency of interaction and acquisition of skills, which enables individuals to perform effectively (Nahrgang, Morgeson, & Illies, 2009). In a high quality mentor-protégé relationship, the mentor discusses current issues relating to the mentee's work and offers insights about the organisational work styles, informal networks, and challenges and opportunities available, which in turn enhance his/her job performance.

Madlock and Lightsey (2010) and Rowland (2012) stated that mentoring helps enhance communication satisfaction, which is a socio emotional feeling derived from positive relational interactions (Hecht, 1978). Further, it is the extent to which employees perceive satisfaction with respect to information and communication environment (Chan & Lai, 2017). Effective communication is a major part of supervisor's/mentor's strategy that results in communication satisfaction (Madlock & Lightsey, 2010). Dasgupta, Suar, and Singh (2013) revealed that perceived supervisory support at the workplace leads to better communication satisfaction. The basic aim of mentoring is to build the proficiency of the mentee to the level of self-reliance, which spreads the communication of ideas across the organisation. The mentor offers a safe environment to the mentee within which they can discuss work related issues and techniques to complete challenging tasks (Lankau & Scandura, 2002). When the mentee has complete information about his/her job, s/he is able to perform his/her job in a better way (Pavitt, 1999). Good communication helps the mentee to keep internal processes running smoothly and helps to create superior relationships with people, both within and outside the organization (Lasater et al., 2014; Shahzad, 2014). On the contrary, poor communication can result in increased uncertainty about situations, relationships, increased occupational stress, and burnout (Ray, 1993). Subordinates perform well when they are satisfied with the communication flow in their organisation. Increased communication satisfaction encourages employees to open up freely and discuss their opinions at the workplace (Shahzad, 2014). Communication satisfaction also grows when mentor communicates to his/her mentee the ways to accomplish a particular task and discuss various issues related to work, which help the mentee to perform well.

Hypothesis 2a. Personal learning mediates the relationship between mentoring and job performance.

Hypothesis 2b. The relationship quality mediates the relationship between mentoring and job performance.

Hypothesis 2c. Communication satisfaction mediates the relationship between mentoring and job performance.

Moderated Mediation

By integrating mediation and moderation relationships, we propose a moderated mediation model. In our model, self-efficacy moderates all the three paths in mediated relationships. So, in the integrated model we shall be evaluating the indirect effect of the interaction of mentoring and self efficacy on job performance through personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction. Same shall be tested through multi-group analyses.

Method

Participants

The population consisted of 1,105 employees working in five banks, namely PNB Bank, SBI Bank, J&K banks, ICICI Bank, and HDFC Bank in Jammu & Kashmir (North India). In order to avoid the problem of common method bias, information has been procured from multiple respondents, i.e., information pertaining to mentoring, personal learning, relationship quality, communication satisfaction, and self-efficacy has been procured from employees, whereas their level of job performance has been procured from their immediate superior.

Measures

Mentoring. This construct included 16 items adopted from Noe (1988). Sample items are “My mentor instructs me about my job”, “My mentor helps me in coordinating my goals”, “I admire by mentor's ability to teach others”, etc.

Personal learning. A self-generated seven-item construct covering two dimensions, i.e., relational job learning and personal skill development of personal learning, was developed on the basis of Lankau and Scandura (2002) and Liu et al. (2009). Sample items are “I prefer to work on tasks that force me to learn new skills”, “I grow and change”, “I try to learn special skills and competence while pursuing work”, “I learn through feedback”, etc.

Relationship quality. An eight-item construct was self-generated for measuring relationship quality, covering trust, support, respect, information sharing, collaborative problem solving, and expectations (Karcher, Nakkula & Harris, 2005; Ragin et al., 2000), including items such as “We respect each other” and “Both of us are there for each other in hour of need.”

Communication satisfaction. A nine-item self-generated construct was used for assessing communication satisfaction after reviewing the research papers by Hecht (1978) and Madlock and Lightsey (2010), including items such as “I can openly communicate my ideas” and “My mentor gives me feedback about my performance.”

Self-efficacy. Originally this scale consisted of 10 items (Riggs, Warka, Babasa, Betancourt, & Hooker 1994). The factor loading of two items were below the threshold value, i.e., less than .50. So, we used only eight items, such as “I do not doubt my ability to do job” or “I have confidence in my ability to do job.”

Job performance. Job performance has been measured with the help of 7 items (Goodman & Svyantek, 1999; Motowidlo & Van, 1994); examples are “He/she timely completes tasks assigned to him/her” and “He/she fulfils responsibilities specified in his /her job description.”

Control variables. The type of bank has been taken as control variable (public and private banks).

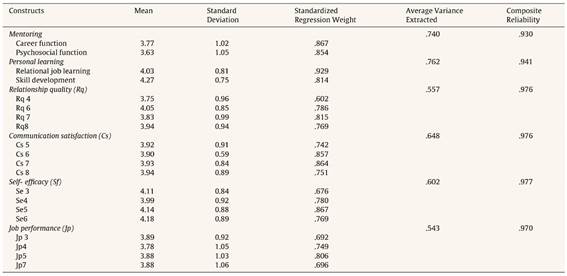

Pilot Survey

A pilot survey was conducted with 100 bank-employees, selected conveniently, in order to achieve a representative sample. Further, data collected at this stage was also used for an exploratory factor analysis in order to identify the factor structure of all the constructs, as some of the constructs were self generated. The test of appropriateness of a factor analysis was verified through a KMO measure of sampling adequacy, where value greater than .50 is acceptable (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2010), which indicated its relevance for further analysis. Statements with factor loading less than .50 were deleted (Hair et al., 2010). The mentoring construct comprised 16 items that got reduced to 6 items and converged under two factors. Similarly, the personal learning construct consisted of 7 items that converged under two factors. Further, communication satisfaction, relationship quality, job performance, and self-efficacy consisted of 9, 8, 7, and 8 items respectively, which got reduced to 4 items in case of all the constructs. The detailed results are presented in Table 2. Internal consistency was also measured with the Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Reliability of all the constructs ranged from .76 to .87 (see Table 2). After establishing reliability, the items retained in each construct were used for the final data collection.

Sample Size

After the pilot survey, the sample size was calculated on the basis of the following formula (Malhotra, 2007):

where X = size of sample, σ = standard deviation, Z = standard score and D = amount of precision or allowable error in the sample.

By applying this formula, the sample size arrived at 292, which was rounded off to 300. So, 300 bank employees and their immediate superiors (n = 300) were contacted. The number of employees from each branch has been selected through proportionate method. Employees from each branch was selected on the basis of the chit method. Two hundred ninety-four employees returned back the questionnaire, out of which 18 questionnaires were incomplete, so these were not included in the study. Thus, the final sample came to 276 complete sets.

Results

Demographic Profile

Out of 276 employees, 54.7 percent are male and 45.3 percent are female. Most employees are having 1 to 3 year of relationship with their mentor (83.3 percent) and 16.7 percent of employees are having more than three years of relationship with their mentor. Most of the employees considered their immediate superior as their mentor (40.2 percent), 33 percent named their colleague whereas 22.8 percent named their hall manager as their mentor. Only 4 percent of the employees considered subordinates as their mentor. Type of bank, i.e., public or private, was taken as control variable and the results revealed no significant impact of this on dependent variables, i.e., personal learning (β = .029, p > .05), relationship quality (β = .006, p > .05), communication satisfaction (β = .056, p > .05), and job performance (β = .049, p > .05). Further, addition or deletion of control variable did not change the relationship, so it has not been shown in the final models (Arnold, Turner, Barling, Kelloway, & Mckee, 2007).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The validity and reliability of the constructs was assessed with the help of CFA. Second order factor models were designed for two constructs as multiple factors emerged after EFA, namely, mentoring and personal learning. Zero order factor models were designed for rest of the constructs. Fit indices of all the models are within the threshold limit, i.e., GFI, CFI values are greater than .90 and RMR is lower than .05 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2007) (see Table 3). Standardized regression weights (> .50) and average variance extracted (> .70) established the convergent validity (Table 4). Further, discriminant validity was also proved by comparing the model fitness of the six-factor model with the one-factor model. The goodness of model fit of the six-factor model (RMR = .053, GFI = .844, AGFI = .813, CFI = .909, RMSEA = .053) is better than the one-factor model's (RMR = .062, GFI = .834, AGFI = .805, CFI = .899, RMSEA = .61), thereby proving discriminant validity (Kluemper, McLarty, & Bing, 2015). Additionally, discriminant validity also got established by comparing the variance extracted with squared correlations amongst different constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The average variance extracted for all the constructs is higher than the squared correlation, thereby proving discriminant validity (Table 5). Reliability of the constructs has been checked through composite reliability (> .70; Table 4).

Table 3 Model Summary of Goodness of Fit Indices.

| Construct | χ 2 /df | RMR | GFI | AGFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mentoring | 5.197 | .056 | .955 | .864 | .947 |

| Personal learning | 3.220 | .027 | .959 | .913 | .960 |

| Relationship quality | 1.759 | .014 | .994 | .969 | .996 |

| Communication satisfaction | 5.125 | .019 | .982 | .910 | .986 |

| Self-efficacy | 3.485 | .017 | .987 | .936 | .990 |

| Job performance | 5.286 | .029 | .982 | .910 | .978 |

Note. χ2/df = chi-square/degrees of freedom, RMR = root mean square residual, GFI = goodness of fit index, AGFI = adjusted goodness of fit index, and CFI = comparative fit index.

Common Method Bias

The common method bias for all the constructs in the study have been examined through common latent factor method (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). In this method, we added a common latent factor (CLF) to our factor structure model, and then connected it to all observed items in the model. Then the standardized regression weights from this model was compared to the standardized regression weights of a model without the CLF. The results revealed that there is no item whose difference is greater than .20 (Jyoti & Bhau, 2016). Therefore, common method bias is not a problem in this study.

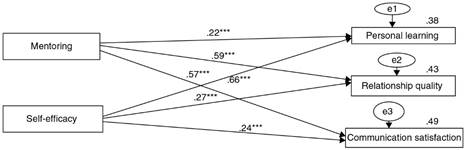

Moderation Effect

SEM was used to check various relations proposed. It is a multivariate technique that seeks to explain the relationship among multiple variables (Byrne, 2010). The various latent constructs were amputated to get single observed variable for each construct, as recommended by Gaskin (2012) when the number of manifest variables is large. In this study we have self-efficacy (metric variable) as moderating variable between mentoring and its outcomes, i.e., personal learning, relationship quality, and communication. Moderation of metric variable is checked through interaction effect in AMOS software (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Gaskin, 2012; Little, Card, Bovaird, Preacher, & Crandall, 2007, p. 223). In this process three models were created, in which the first model revealed that mentoring significantly affects personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction (Figure 2). The second model revealed a significant impact of mentoring and self-efficacy (moderator) on personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction (Figure 3). The third model revealed that the interaction of mentoring and self-efficacy is significantly predicting personal learning (SRW = .383, p <.001), relationship quality (SRW = .567, p <.001), and communication satisfaction (SRW = .648, p <.001) and the model fit indices are also within the threshold limit (Figure 4) (RMR = .012, GFI = .933, NFI = .962, CFI = .963). Further, the R 2 of the third model is better than the other two models’ (Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Figure 2 Impact of Mentoring on Personal Learning Relationship Quality and Communication Satisfaction (Model 1).

Figure 3 Impact of Mentoring and Self-efficacy on Personal Learning Relationship Quality and Communication Satisfaction (Model 2).

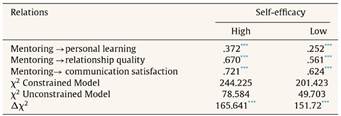

Additionally, we also checked the moderation through multi-group analysis by dividing the data into two groups, i.e., high and low. Data has been centred around the mean of the moderating variable, i.e., self-efficacy. Firstly, the parameters for the hypothesized relationship are constrained to be equal and in the second step the parameters are not constrained. If the difference between the two models is significant (p < .05), that means the variable used for splitting the sample moderates the relationship (Jimenez-Jimenez & Sanz-Valle, 2011). The results revealed that the relationship between mentoring and personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction are significant for the constrained and unconstrained models in both groups. Even though the relationship between dependent and independent is positive for both groups but this, relationship is stronger and significant when the level of self-efficacy is high (Table 6). Therefore, it is concluded that self-efficacy moderates the relationship between mentoring and personal learning, mentoring and relationship quality, and mentoring and communication satisfaction.

Further, a series of simple slop was conducted, which reveals that self-efficacy moderates the relationship between mentoring and personal learning, mentoring and relationship quality, and mentoring and communication satisfaction (Figures 5-7). Hence, hypothesis 1a, 1b, 1c are accepted.

Mediation Effect

In this research there are three mediators, namely, personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction, between mentoring and job performance relationship.

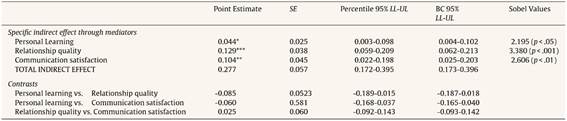

The mediation effect was checked through the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982). Sobel test checks whether the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator variable is significant or not. The result revealed that an indirect effect is significant for all the three mediators and the same is shown in Figure 8 and Table 7.

Figure 8 Mediating Role of Personal Learning, Relationship Quality and Communication Satisfaction in between Mentoring and Job Performance.

Table 7 Multiple-mediation Analysis Personal Learning, Relationship Quality and Communication Satisfaction in between Mentoring and Job Performance.

Note. BC = bias corrected; 5000 bootstrap samples, LL = lower level, UL = upper level

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Further, we have three mediators at the same level. This is the case of multiple-mediation, so, in order to check multiple-mediation, we adopted Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) methodology. They recommended bootstrapping of specific indirect effects to reduce omitted parameter bias. Further, including multiple mediators in one model helps to estimate the relative effect of the specific indirect effect associated with all mediators (Preacher & Hayes, 2008, p. 881). In Figure 8 the total effect of mentoring on job performance is significant (c = .408, p <.001). Further, the direct effect of mentoring on job performance became insignificant (c’ = .131, p>.05), which suggests complete mediation. Table 7 represents the parameter estimates for the total and specific indirect effects on the association between mentoring and job performance as mediated by personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction. The total indirect effect and the specific indirect effects of personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction are all significant, as reflected by confidence intervals, as upper and lower confidence level do not contain zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Further, inspection of the contrast revealed a significant difference between specific indirect effect of personal learning and relationship quality (Z = 1.9, p <.05), indicating that the relationship quality had a significant greater indirect effect on job performance as compared to personal learning. Therefore, hypotheses 2a, 2b, and 2c are accepted.

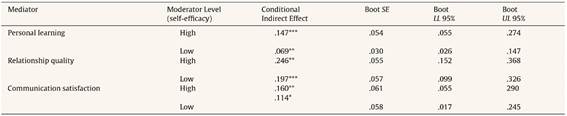

Moderated Mediation

Finally, we investigated the full model through structure equation modelling using the maximum likelihood method in the AMOS programme. In this integrated model we assessed the strength of the relationship between mentoring and job performance through the mediation of personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction at high and low level of self-efficacy. The moderated mediation is established when the conditional indirect effect of mentoring on job performance in the presence of a moderating variable is significant. The result revealed that moderated-mediation effect of mentoring on job performance through personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction for both groups is significant, as the indirect relations are significant with 95 percent confidence interval (Table 8).

Discussion

Mentoring has been researched for more than two decades and is recognised equally by academicians and practitioners. This study highlights the process that enhances the relationship between mentoring and job performance through moderating and mediating variables. This study explores three issues:

The moderating role played by self-efficacy in between mentoring and personal learning, mentoring and relationship quality, and mentoring and communication satisfaction relationships.

The mediating role played by personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction in between mentoring and job performance relationship.

The interaction effect of mentoring and self-efficacy on job performance through the mediation of personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction.

The results of the present study revealed that the impact of mentoring on personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction is boosted when the mentee is efficacious. Efficacious subordinates/mentees are capable of absorbing more from work experience, i.e., mentoring enhances mentee's personal learning (Lankau & Scandura, 2002). Mentoring gives more benefits when it is clubbed with self-efficacy, because a mentee cannot learn anything when his/her inner urge cannot force him/her to do so. Self-efficacious mentee is more capable and competent to learn more from mentoring support. He/she learns from regular interaction, getting together and the information sharing process, which helps in boosting personal learning capabilities. Guidance and coaching provided by the superior/mentor help the subordinate to learn special skills that help him/her enhance his/her competences. Efficacious employees/mentees learn more through various assignments in the mentoring relationships and have the urge to gain more and more, which gives them the opportunities to continuously grow and learn new skills, thereby enhancing employees’/mentees’ personal learning. Further, mentoring helps in establishing a healthy relationship between mentor and mentee. This relationship is more strengthened when mentoring is integrated with the mentee's self-efficacy. The efficacious mentee is able to complete all the tasks assigned by the mentor in a better way, which helps in creating a positive image in the mind of the mentor and brings them closer. A mentor with a positive mentee image interacts more with efficacious mentees. The frequent interactions help to built congenial relationship and ultimately results in a better relationship quality between the two. In addition to this, self-efficacious mentees with mentoring support feel more confident and are able to communicate their queries and ideas without hesitation to the mentor. Mentor in turn solves problems and communicates necessary information to efficacious mentees with positive attitude. Nowadays organisations usually keep their employees informed about various developments occurring in the organisation. Mentor serves as a channel of communication regarding updated information to the mentee. A self-efficacious employee/mentee is able to grasp this information in a better way due to his/her intellectual capabilities. If there is any confusion regarding any aspect, the efficacious mentee is able to clarify the same without any hesitation in a better manner. Thus, the mentor feels happy to share, listen, and pay attention with a more efficacious mentee than with a less efficacious mentee, which enhances communication satisfaction among mentees.

Furthermore, mentoring effectiveness is reflected in better subordinates’ job performance through their learning quotient, positive communication, and better relationship quality. The buddy approach (assignment of a mentor to the new entrants) used in the banking sector helps to improve the learning capability of the subordinate by providing a better solution to the work related issues and hence improving performance. Mentoring instils in mentees a sense of competence, identity, learning skill, and effectiveness in his or her role, which helps in enhancing personal learning. Further, personal learning is a useful asset, which is essential for good performance. Mentee's performance is directly affected by skill and competence, which are developed through personal learning. Mentor supports his/her mentee at every stage. His/her support is reflected in three ways. Firstly, through career support, that helps mentee to develop their career. Secondly, through psychosocial support, in the form of regular discussion and information sharing, which helps in increasing mentee sense of competence, identity, and work-role effectiveness. Thirdly, the mentor serves as a role model in terms of appropriate attitudes, values, and behaviours for the mentee. All this helps in building a sound relationship between mentor and mentee. Further, mentor's behaviour involves building trust, inspiring a shared vision, encouraging creativity, and emphasising development, which results into establishing a healthy relationship between both of them. This sound relationship between them helps the mentee to improve job performance. Mentoring support helps the mentee to acquire the necessary skills and experiences needed to perform work, and protect them from uncertainties. Mentor also helps the mentee in building confidence, overcoming pressures, assisting in personal life, and teaching with examples, which helps in creating communication satisfaction. When the mentor listens, pays attention to mentee, and gives regular feedback about performance, increases the level of job performance. Positive feedback by mentor boosts mentee's morale and enhances his/her job performance.

Finally, the combined effect of mentee's mentoring and self-efficacy indirectly affects job performance through personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction. When a self-efficacious mentee gets positive mentoring, it improves his/her attitude towards learning, helps to build quality based relationship between mentor and mentee, and generates satisfaction with communication patterns, which ultimately results in better job performance.

Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the mentoring literature. This investigation is important for academicians and researchers alike. This investigation adds to the prior body of knowledge in mentoring literature by evaluating the moderating and mediating variables between mentoring and job performance. We empirically proved the moderating role of self-efficacy between mentoring and personal learning, mentoring and relationship quality, and mentoring and communication satisfaction. Further, the mediating role of personal learning, relationship quality, communication satisfaction between mentoring and job performance has also been proved. Finally, we have also proved that interaction of mentoring and self-efficacy indirectly affects job performance through personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction by conducting multi-group analysis.

Managerial Implications

In practical terms, this study has implications for manager as well as for practitioners. The results reveal positive impact of mentoring on personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction. Organisations that practise mentoring should take necessary measures to implement mentoring by developing detailed instruction guides for the mentor and mentee. Buddy approach (assignment of an experienced person to new entrants) should be used in order to increase a learning atmosphere. Mentor should advise a mentee about promotional opportunities and help him/her in achieving professional goals. Further, the results show that an individual's self-efficacy is an important moderating factor that boosts the impact of mentoring on personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction. Although self-efficacy is person specific, yet, organisations should enhance self-efficacy of their employees by making them confident about their ability to do the work. Organisations should create a strong belief in their employees’ minds that they have the skill necessary to do a particular task and handle any complex situation easily. The low efficacious employee should be made a part of the team where collective effort is valued. Efficient teams help to increase the knowledge as well as the operational capability of all the members. Management should create such norms which encourage them to learn from mistakes and risk taking, which can boost the efficacy level of the employees. The manager/superior should give proper feedback about the employee's performance, which helps the employee in recognising his/her strengths and weaknesses. Further, proper coaching, counselling, and grooming help to build self confidence among employees. The results of this study suggest that personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction act as mediating agents between mentoring and job performance. In order to enhance personal learning, relationship quality, and communication satisfaction, a mentor should encourage the mentee to discuss personal and professional problems with him/her. He should inculcate such an atmosphere in which mentee is comfortable to consider mentor as a friend and go often or socialise with each other, which strengthens their relationship. It also promotes growth through enhanced learning, better utilisation of time, effort, and resources and enriches vibrancy and productivity. Further, management should establish such a mentoring culture that encourages mentor and mentee to take interest, exhibit openness, affection, and be there for each other whenever needed. Mentor should encourage the mentee to think/talk freely and discuss work related problems there by solving problems together, which brings them close to each other and increases their communication level. Further, the management should encourage the mentor to provide a learning environment by conducting interacting session with their colleagues in the workplace, and by providing challenging assignments to their employees. A mentor should also motivate mentees to build relationship quality and communication satisfaction. This component should help improve performance. Moreover, proper evaluation programmes should be conducted to force an employee/mentee to perform well.

Social Implications

Mentor provides not only career related support but also psycho-social support to a protégé by helping him/her to solve life related issues too. So, management must develop formal as well as informal mentoring systems, so that employees are able to establish work-life balance. Further, mentoring develops the confidence level of the protégé, which helps him/her to solve social issues in a much better way. Mentoring encourages employees to speak openly and learn new things, which helps them to create a networking within the organisation as well as in the society. Outspoken and confident employees/protégés make their own ways to grow in the society and handle personal as well as professional problem easily.

Limitations and Future Research

Immense efforts have been done to make the study valid and reliable but still there are certain limitations, which can be rectified in the future. Firstly, the study is cross sectional in nature; in the future, a longitudinal study can be conducted. Secondly, more outcomes of mentoring can be taken into consideration in the future for better understanding of the concept. Further, the role of other variables, like longevity of relationship, can be explored between mentoring and its outcomes.