Introduction

Problem Situation and Purpose of the Study

The field of personnel selection is subject to major changes. In the pre financial crisis era until approximately the year 2008, it was commonplace to hire future employees for a specific job description. The main focus those days was to match the candidate with the tasks to be done and the corresponding responsibilities to be taken. However, since the economic recovery that started around the year 2012, many companies have rigorously organised themselves differently. Ever since, issues like adaptability and technological developments have been emerging. This resulted in a renewed approach on recruiting and hiring, in which both the initial fit between the job profile and the candidate as well as his future development opportunities or potential are assessed. Christensen and Schneider (2010), McDowell (2013) and Dos Santos and Russi De Domenico (2015) showed that today’s constantly changing workplace requires from the employee the condition to be an authentic talent that is able to collaborate with other talents through shared values, seen as the stable factor within a less secure working environment. With this in mind, many companies try these days to select those types of employees who are able to disseminate the organisation’s values beyond matching with a specific job profile.

This renewed approach has great and tangible consequences for the way organisations fit their employees with the new and continuous changing business requirements. Next to selecting employees on their personal characteristics and skills, the match with the organisation’s values is more and more becoming a critical success factor. This pleads for a joint approach on personality traits and work values that, in conjunction, give meaning to one’s abilities and fit with the specific organisation’s characteristics. This holistic way of studying individual characteristics aims to contribute to value congruence, defined as minimising the distance between individual and organisational characteristics and motives (Cable & Edwards, 2004; Uçanok, 2010). In studying the value congruence, Roberts et al. (2006) elaborated personal characteristics in personality traits and work values, following the historic segregation of attributes from value judgments (Allport, 1937). This way of elucidating a person’s characteristics is said to contribute to a more long-term tenable fit between the employee and the constantly changing organisation, transcending the fit with a specific job profile. However, the association between personality traits and work values has rarely been studied (Parks & Guay, 2009).

All the few studies that have been conducted on this subject (e.g., Berings, De Fruyt, & Bouwen, 2004; Furnham, Petrides, Tsaousis, Pappas, & Garrod, 2005; Parks, 2007; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015) assume an association between them. However there is little agreement yet on which personality traits and work values relate stronger (Parks, 2007; Parks-Leduc, Feldman, & Bardi, 2015). A possible explanation might be that all previous studies were constructed on the five major clusters of personality traits, known as the Five Factor Model (Costa and McCrae, 1985). In the present study it is expected that elaborating these personality factors into their underlying facets will contribute to further elucidating their assumed relations. With this, the study follows the suggestion of Ones & Viswesvaran (1996) that the identification of employee characteristics in personnel selection from a developmental perspective pleads for the use of narrower personality traits instead of the use of broader traits. Work values, in the present study, are dealt with as the ten values of the universal values model, or UVM (Schwartz, 1992). In studying their associations with personality facets, the paper follows the differentiation of these work values in two clusters of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors, found in the studies of Daehlen (2008), Bruyninckx and Valkeneers (2010), and Bipp (2010). This way of ordering work values is expected to contribute to further clarifying the associations between personality facets and work values in a work-related context.

Next to the increasing attention for a long-term tenable fit between the employee and the organisation, the labour market is confronted with the issue of ageing. The reduced social security ensures that people continue to work longer and longer. This observation emphasizes the importance of an age-dependent match next to the long-term tenable fit between the employee and the organisation. Combining both is expected to result in a more sustainable match. Earlier research suggested that both personality traits and work values evolve over time (Costa & McCrae, 2006; Johnson, 2001; Schwartz, 2006). Therewith, to further increase the insight into the personality facets and work values in a work-related context, this present study examines the role of age in its mutual association. This is expected to contribute to establishing both a long-term tenable and an age-dependent fit between an individual’s characteristics and the constantly changing organisation. With this, the central research question of this study is: “What is the role of age in the association between personality facets and work values?”

One of the sectors in which this long-term tenable and age-specific association between facets and values is a current topic is the banking sector. Following the financial crisis, banking employees were confronted with major changes in the way they were used to exert their jobs. The sector faced an ascending tension between the liability for a lack of duty of care and a growing distrust of clients. In order to adjust this downward spiral, the sector responded with newly defined company values. Within this change process, both the young and older employees were addressed for a quick adaptation of both their skills and their attitudes. The effects of these changing circumstances were the strongest for the front office employees, since they maintained direct contact with their clients. Besides, characteristic for the banking sector was the presence of both young professionals and senior staff. Therefore, in order to study the role of age in the association between personality facets and work values in an appealing environment, this study is conducted under a sample of Dutch commercial business or private bankers.

Theoretical Framework

Personality Facets

Personality theory is about the systematic study of the similarities and differences in personality between people, in which personality means how the individual acts (1) in his social environment, (2) with other people, and (3) in different situations (Ekkel & Ranty, 2006). Personality itself is conceptualised as a stable system of tendencies to act, think, and feel in a certain way (Digman, 1990; Guilford, 1959). Today, the most popular model of personality used for investigating employee personality is the five factor model, or FFM (Costa & McCrae, 1985). This model suggests that personality, viewed from a trait approach, consists of five major clusters of personality characteristics: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, also known as the OCEAN-model (Digman, 1996). Each of the five factors of the FFM contains six subscales, known as personality facets (Costa & McCrae, 1991). These 30 facets, as presented in Table 1, jointly give a detailed view on the composition of the five main factors. When the 30 facets are factor-analysed, the five factors emerge, each defined by high loadings from six facets of the same scale (Costa & McCrae, 1991). The FFM underlies different personality tests, like the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1985), the NEO-FFI (Costa & McCrae, 1991), and the FFPI (Hendriks, Hofstee, & De Raad, 1999). In investigating the intrapersonal fit between personality facets and work values, the present study uses these 30 personality facets behind the five clusters of the FFM in order to further elucidate which personality traits and work values relate the strongest (Parks, 2007; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). With this, the study follows Ones & Viswesvaran (1996) in their view on the bandwidth-fidelity dilemma in personality measurement for personnel selection purposes.

The five factors differ from values, defined as the criteria people use to evaluate actions, people, and events (Rokeach, 1973), in three ways that support their separate conceptual treatment (Bilsky & Schwartz, 1994): (a) traits are seen as descriptions of the unique attributes beyond observed behaviour, whereas values are criteria used to judge or appreciate the desirability of performed behaviour, (b) traits vary in terms of how much of a characteristic individuals exhibit, whereas values vary in terms of the importance that individuals attribute to particular goals, and (c) personality traits describe actions presumed to emerge from ‘what persons are like’ regardless of their intentions, whereas values refer to the individual’s intentional goals that are available to consciousness. In order to investigate the intrapersonal fit between personality facets and work values, the next section further elaborates the latter.

Work Values

Schwartz (1992) defines values as desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in people’s lives. The crucial content aspect that distinguishes among values is the type of motivational goal they express (Schwartz, 2006). Work values are seen as the expressions of basic values in the work setting. Schwartz (1992) introduced his universal values theory, in which he presented four value factors: self-transcendence, conservatism, self-enhancement, and openness to change, jointly consisting of ten value types. Each of the ten basic values can be characterised by describing its central motivational goal. Even though the types of human motivation that values express and the structure of relations among them are universal, individuals differ substantially in the relative importance they attribute to their values, that is, individuals have different value priorities that derive from adaptation to life experiences (Schwartz, 2006).

Daehlen (2008) subsequently differentiated work values in intrinsic and extrinsic values. This distinction identifies work values as being either developmental or reward-driven. According to this classification, typical intrinsic values included interesting and challenging work, matching with the two factors: openness to change and self-enhancement of Schwartz (1992). High income, job security, and helping others are typical extrinsic values that correspond with conservatism and self-transcendence factors. In spite of the distinctions between personality traits and work values, it can be difficult to disentangle the two constructs in practice (Parks & Guay, 2009), because the mutual interaction both confer to human abilities. Therefore, to work on an improved insight in the interplay between these two personal characteristics, the next section will focus on the interrelatedness of facets and values.

The Association between Personality Facets and Work Values

In line with the assumed direction of causality (Furnham et al., 2005), this study investigates the association between personality facets and intrinsic and extrinsic work values, studying the impact of facets on values rather than vice versa. This direction follow the conceptualisation and joint interactions of Bilsky and Schwartz (1994). Studies conducted on this subject, however, do not agree on which associations are stronger or the strongest.

Different researchers have studied the association between personality traits and work values. Some of them included demographic variables like gender, age, and education as part of their joint explanatory relation with a declared work-related aspect. Berings et al. (2004), in their study on the incremental validity of work values to predict vocational interests over and above personality traits, found that especially conscientiousness and extraversion factors positively explained work values in general. Furnham et al. (2005), in their two-study investigation into the relationships between the personality factors and an individual’s work values for both British and Greek employees, found that agreeableness, extraversion, and openness were robust predictors of work values in general. In her subsequent meta-analysis of eleven studies on the relation between personality traits and work values, Parks (2007) concluded that mainly agreeableness and openness had the strongest relations with work values in general. She emphasised the lack of agreement on which relations are stronger or the strongest. Bruyninckx & Valkeneers (2010) found, as part of their study on the influence of personality on work motivation, that extraversion and openness had a stronger, positive relationship and agreeableness had a stronger negative link to intrinsic values. Bipp (2010) studied the relationship between personality traits and the valuation of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors. She found that extraversion and conscientiousness related positively and agreeableness related negatively to intrinsic motivation factors. Parks-Leduc et al. (2015), in a meta-analysis of 60 papers, studying relationships between personality traits and Schwartz’s values, demonstrated that traits and values are distinct constructs. Support was found for the premise that openness is more strongly related to values, neuroticism is least related to values and agreeableness, conscientiousness and extraversion are moderately related to values.

Because of the differences in the outcomes of the above mentioned studies, the conclusion of Parks (2007) and Parks-Leduc et al. (2015) on the lack of agreement remains up-to-date and relevant. However, based on the similarities within the different studies, there seems to be a tentative indication that mainly the extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness factors have a stronger positive relation with intrinsic work values than with extrinsic work values. The agreeableness and neuroticism factors seem to have a stronger positive relation with extrinsic than with intrinsic work values. Possibly the intrinsic values are, just like traits, part of the more enduring aspects of people’s essential orientations towards employment (Cook, Hepworth, Wall, & Warr, 1981, p. 132). Following the suggestion of Ones and Viswesvaran (1996) in further elucidating which personality traits and work values relate stronger, the present study investigates its relationships on a personality facet level. Next to this, work values are differentiated in two clusters of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors (Bipp, 2010; Bruyninckx & Valkeneers, 2010; Daehlen, 2008). It is hypothesized to find stronger positive relations between the personality facets behind the extraversion, conscientiousness, and opennes factors and intrinsic work values and stronger positive relations between the personality facets behind the agreeableness and neuroticism factors and extrinsic work values.

H1a: Personality facets behind the extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness factors show a stronger positive relation with intrinsic than with extrinsic work values.

H1b: Personality facets behind the agreeableness and neuroticism factors show a stronger positive relation with extrinsic than with intrinsic work values.

In line with the indication of Johnson (2001), Costa and McCrae (2006), and Schwartz (2006) that age influences the development of both personality traits and work values, this paper continues with studying the question to what amount age influences personality on a facet level. Therefore, the next section will focus on earlier studies about the effect of age on the development of employee personality, viewed from a trait approach.

The Influence of Age on the Development of Personality

Until around 1994, the generally accepted view on personality was that it stopped changing in adulthood (McCrae & Costa, 1994). For example, Caspi and Roberts (1990) confirmed, through a longitudinal study amongst 1,000 children, the conceptualisation of an inborn and immutable set of personality traits. Ever since, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of personality trait change in adulthood have forced a re-evaluation of this assumption (Roberts et al., 2006). Research now shows that personality continues to change in adulthood often into old age, and that these changes may be quite substantial and consequential.

Costa and McCrae (2006) found a modest change from the age of 45 years and older. They concluded that extraversion and neuroticism decline, whereas agreeableness and conscientiousness increase with age while openness first increases and then decreases. In their study, Costa and McCrae (2006) used the three age-arrays of Rabinowitz and Hall (1981): (1) early career with age 21-35, (2) midcareer with age 36-49, and (3) late career with age 50 and over, building on the three career stages of Super (1957): (1) trial stage, (2) stabilization stage, and (3) maintenance stage. In subsequent research, Roberts, Wood, and Caspi (2008) found that personality traits increase in rank-order consistency throughout lifespan. Specht et al. (2014) confirmed these findings, noting that mainly the differences between people in their younger years until around 35 years and people of around 45 years and older appeared to be the most obvious. These studies seem to suggest that personality change is, in part, predictable, because it follows age development, whereas the most notable change seems to take place in the late midcareer age. Therefore, it is hypothesized to find a higher rating for extraversion, neuroticism and openness in a group of people until the age of 35 years. It is hypothesized to find a higher rating for agreeableness and conscientiousness in the group of people of 45 years and older.

H2a: People until the age of 35 years give a higher rating to the personality facets behind the extraversion, neuroticism, and openness factors than people of 45 years and older.

H2b: People of 45 years and older give a higher rating to the personality facets behind the agreeableness and conscientiousness factors than people until the age of 35 years old.

The Influence of Age on the Development of Work Values

Next to the assumed effect of age on the development of personality traits, different researchers have indicated an effect of age on the maturation of work values as well. Cherrington, Condie, and England (1979) found that the individual development of work values, just like personality, is significantly influenced by age, even when the effects of income, education, gender, seniority, and occupational level are being controlled for. This seems to be confirmed by Schwartz (2006), who concludes that individuals own different value priorities that develop from the adaption to life experience and therefore derive from an increasing age. Rhodes (1983), through a review of more than 185 studies, examined age-related differences in attitudes, behaviours, and values. She found that each of the three age-arrays of Rabinowitz & Hall (1981) has its own set of strongly appreciated values. Noticeable in her study is that she found that the importance of needs for extrinsic factors increases with the development in career stage, whereas the importance of intrinsic factors decreases. Inglehart (1997) confirmed the outcomes of Rhodes (1983) by demonstrating that, linearly measured, older people give, as a result of a cohort effect, higher priority to economic security and stability, whereas younger people give preference to self-expression and quality of life. Johnson (2001) concludes that, on average, young people in their early career, attach lesser importance to materialist job rewards than older workers, reaffirming Cherrington et al.’s (1979), Rhodes’ (1983) and Inglehart’s (1997) views. Vecchionea, Schwartz, Alessandria, Döringe, and Castellania (2016) examined four types of stability and change in values during young adulthood. The study showed that the mean importance of conservation, self-transcendence, and power values increased over time, the mean importance of achievement values decreased, and openness to change values remained stable.

These findings seem to indicate a strong difference in appreciated work values between people in their early career and those in their mid- or late career stage. More specific, these studies seem to indicate that the change in values follows age development, in a sense that people give higher priority to intrinsic values until their midcareer, whereas people later in their career seem to appreciate extrinsic values more. Therefore, it is hypothesized to find a higher rating for intrinsic work values in the group of people until the age of 35 years. And it is hypothesized to find a higher rating for extrinsic work values in the group of people of 45 years and older.

H3a: People until the age of 35 years give a higher rating to intrinsic work values than people of 45 years and older.

H3b: People of 45 years and older give a higher rating to extrinsic work values than people until the age of 35 years old.

The Influence of Age in the Association between Traits and Values

The above mentioned studies on the separate development of both traits and values seem to indicate a transition point at the end of the midcareer age, which begins at the age of around 45 (Rabinowitz & Hall, 1981). People until their midcareer seem to target on the so-called myself-oriented characteristics (extraversion, neuroticism, openness, intrinsic values), whereas people from the end of the midcareer appear to focus on the fellow human-oriented characteristics (agreeableness, conscientiousness, extrinsic values). Therewith, traits and values seem to affect one another, whereas the type of significant positive associations evolve over time. More specific, it is hypothesized to find a significant positive relation between the facets behind extraversion, neuroticism, and openness and intrinsic values for people in their early career until the age of 35 years. Next to this, it is hypothesized to find a significant positive relation between the facets behind agreeableness and conscientiousness and extrinsic values for people in their late midcareer starting at the age of 45 years.

H4a: Age influences the association between the personality facets behind extraversion, neuroticism, and openness and intrinsic work values in the sense that this association is stronger for people until the age of 35 compared to people of 45 years and older.

H4b: Age influences the association between the personality facets behind agreeableness and conscientiousness and extrinsic work values in the sense that this association is stronger for people of 45 years and older compared to people until the age of 35.

Method

Participants and Procedures

This study investigates the moderating influence of age in the association between facets behind the personality factors and work values of Dutch commercial business or private bankers. In this respect, the effects of the changing environment are expected to be strongest for the front office employees whereas the role of a commercial business or private banker is seen as a typical front office job profile. Participants (N = 465) completed an assessment procedure as part of their personal development program during the period 2008-2013. Afterwards, permission for the use of their results was asked in order to prevent any bias of social desirability aspects. The participants completed both the 300-item Dutch personality test, or NPT (Van Thiel, 2008a) and the 140-item Dutch work values test, or NWT (Van Thiel, 2008b) online. Gender, age, and educational level were reported. All items (300 NPT and 140 NWT) were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. Item scores were summarised as sum scores for each personality facet and work value. Sum scores were converted to standardised Z-scores, to precisely compare the scores on the different variables. After an explanation of the testing procedure by a certified test psychologist, questionnaires were completed in approximately 45 minutes, with a small coffee break in between the two tests. All participants completed the entire questionnaires. The average of the 465 respondents (182 female, 282 male) was 37.12 years (SD = 9.16), with 44.5% until the age of 35 years, 33.8% with an age between 36 and 44 years and 21.7% of 45 years and older; 21.7% of the respondents held a vocational degree and 78.3% owned a university degree.

Measures

Measurement of personality facets. For the measurement of personality facets, the NPT (Van Thiel, 2008a) was used. This measure is a Dutch translation, adaptation, and extension of those parts of the International personality item pool, or IPIP (Goldberg et al., 2006), measuring dimensions highly similar to those of the NEO PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1985). The questionnaire measures the five personality factors and its 30 underlying facets. Analyses of the 300 items on a 5-point Likert scale, Cronbach’s alpha and factor analyses were carried out on a sample of 577 respondents in the Netherlands (Van Thiel, 2008a). The domain scales show internal reliabilities which range from .70 to .92.

Measurement of work values. Work values are measured with the NWT (Van Thiel, 2008b). This test measures scales highly similar to the 12 values of the Super’s work values inventory, revised, or SWVI-R (Robinson & Betz, 2008) plus two extra values, both derived from the 1970 version of the SWVI (‘aesthetics/management’ and ‘altruism’). The SWVI is based on the universal values theory (Schwartz, 1992) and revealed good reliability results which range from .72 to .88. Analysis of the 140 items of the NWT (Van Thiel, 2008b) on a 5-point Likert scale, Cronbach’s alpha and factor analyses were carried out on a sample of 510 respondents in the Netherlands. The domain scales show internal reliabilities which range from .74 to .92.

Following Schwartz (1992), Ros, Schwartz, and Surkiss (1999), and Daehlen (2008), this study categorises the 14 NWT work values into seven intrinsic work values:

Independence: work of which one determines the content himself and that can be carried out in one’s own way.

Creativity: work in which there is room for inventing innovative ideas.

Variety: work that offers variety and varying assignments.

Mental challenge: work in which there is room for the ambition to further develop oneself.

Supervision: work in which one determines what others have to do and in which one can influence decisions.

Prestige: work from which one can derive status and prestige.

-

Achievement: work in which ambition and individual performance are valued and rewarded.

and seven extrinsic work values:

Aesthetics/management: work that consists of fixed activities and routines.

Security: work with certainty about one’s job and future.

Income: work with which one earns a lot of money.

Lifestyle: work that goes well with one’s private life and connects with one’s free time.

Work environment: work that is carried out in a nice building in a pleasant workspace under favourable working conditions.

Co-workers: work in which there is pleasant social interaction with nice colleagues.

Altruism: work in which one is committed to others.

Data Analysis

This study used SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., 2015) to conduct a quantitative analysis of a set of (1) 14 dependent work values, (2) 30 independent personality facets behind the five personality factors, (3) two background variables, i.e., gender and educational level, and (4) one moderating variable, i.e., age. Age was measured on a linear scale and reversed to two age groups. There were no outliers in the dataset. A correlation matrix was created to test the coherence between the variables. Next, an independent samples t-test was conducted to estimate the effect of the gender and educational level background variables on the personality facets and on the work values. After that, multicollinearity was assessed on the basis of the significant correlations between the explanatory variables. The criterion in this respect was that correlations should not exceed the value of .80 (Ten Hacken, 2009).

A stepwise multiple linear regression analysis of the dependent NWT work values, the independent NPT personality facets, and the background variables was conducted. The regression models were estimated with the F-value at a significance level of 5% where the values were explained based on the personality facets and the significant background variables. In order to determine the moderating influence of age, interaction terms with age were calculated for each of the independent NPT personality facets and the two background variables, gender and educational level. Then a stepwise moderation analysis with multiple linear regression analyses was conducted on the NWT work values, the NPT personality facets, and the interaction terms with age. Since the study aimed to measure the strength of the relationships, a moderation analysis instead of a mediation analysis was conducted.

Results

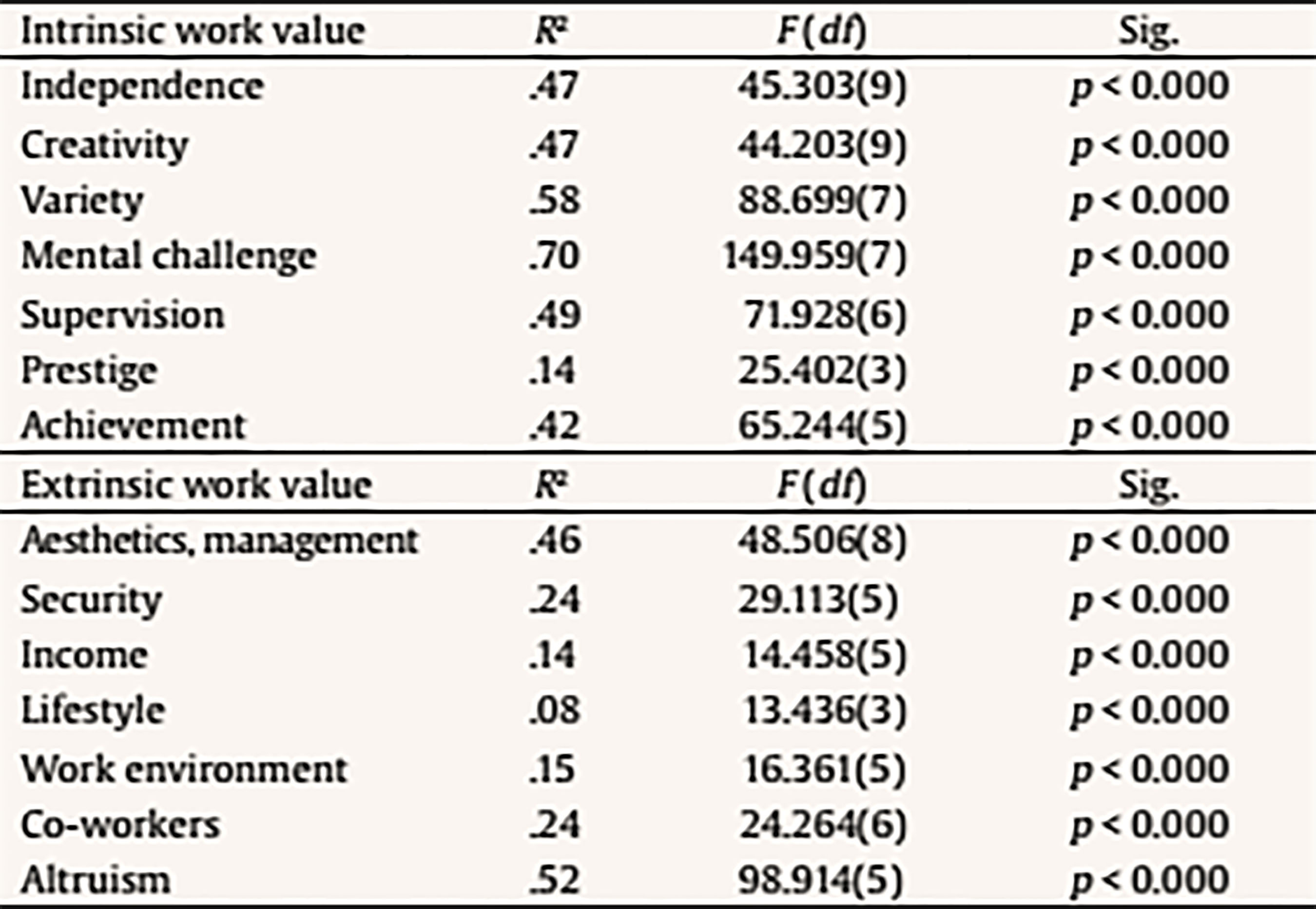

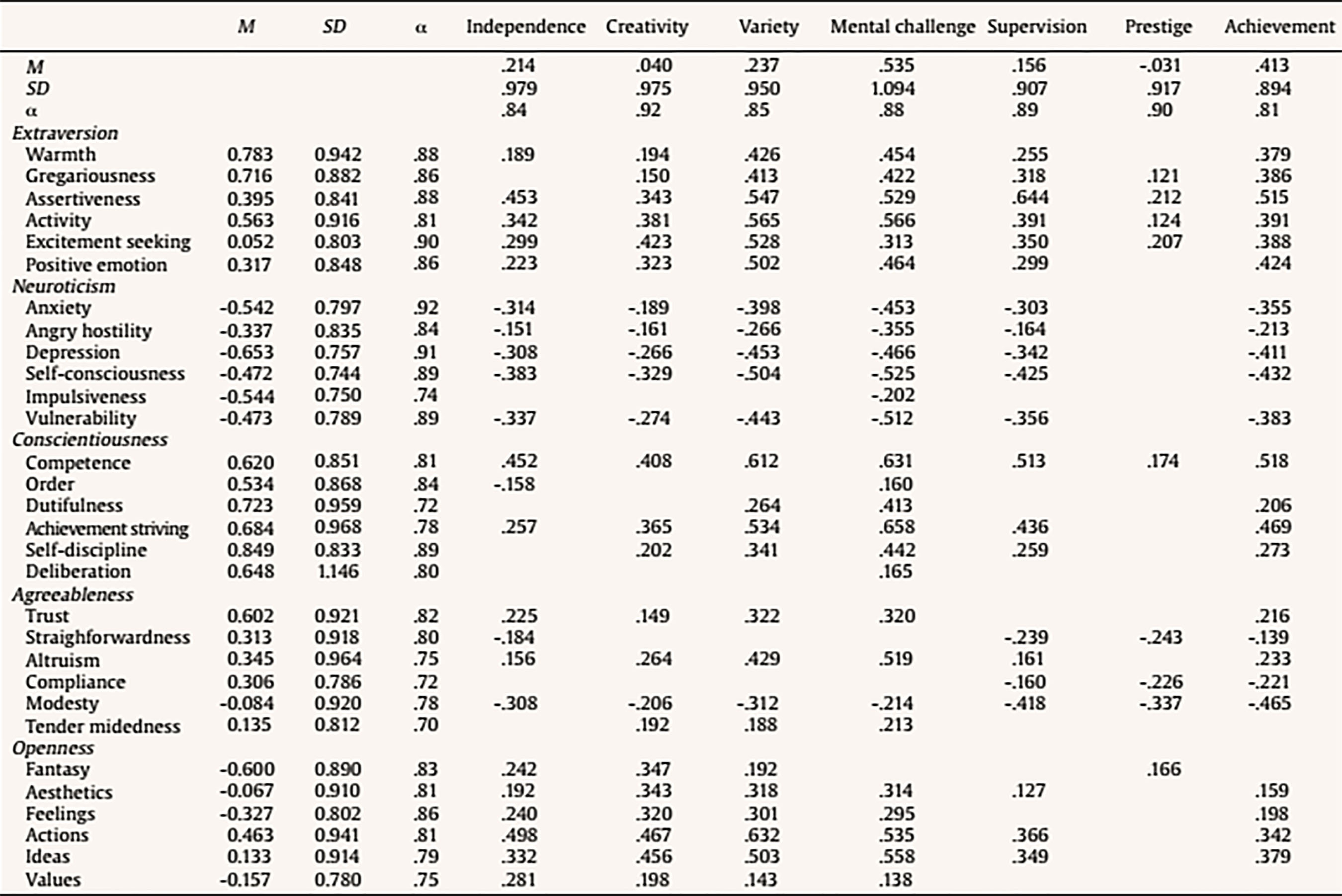

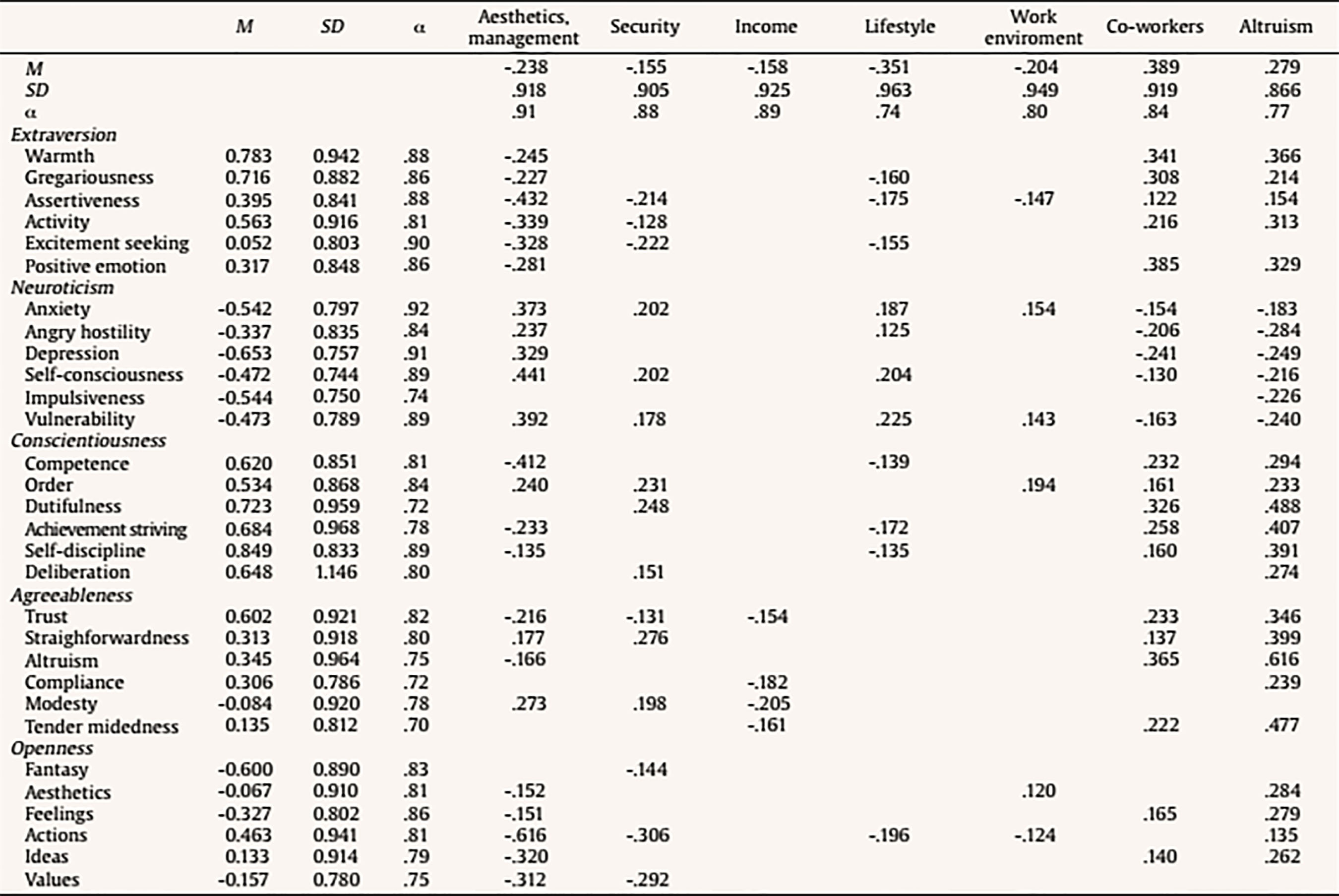

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha, and inter-correlations for the intrinsic work values and the personality facets behind the five factors. The facets behind extraversion related positively to six of the seven intrinsic work values. Five of the six facets behind neuroticism related negatively to six of the seven intrinsic work values. The facets behind conscientiousness related positively to mental challenge as the intrinsic value. Its facet achievement striving showed a positive relation to six of the seven intrinsic work values. The facets behind agreeableness showed a somewhat contradictory picture. The altruism facet related positively to six of the seven intrinsic values, whereas the modesty facet related negatively to all of the intrinsic values. The majority of the facets behind the openness factor related positively to five of the seven intrinsic work values.

Table 2 Means, Standard Deviations, Cronbach’s Alpha and Inter-correlations for the Intrinsic Work Values

Note. All correlations are significant at the p < .01 level (2-tailed).

Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics of means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha, and inter-correlations for the extrinsic work values and the personality facets behind the five factors of the NPT. The facets behind extraversion showed a somewhat contradictory picture. All its facets related negatively to the aesthetics/management extrinsic work value, whereas the majority of its facets related positively to co-workers and altruism. Five of the six facets of neuroticism related positively to aesthetics/management and negatively to co-workers and altruism. The facets behind conscientiousness related positively to co-workers and altruism, whereas three of its facets related negatively to aesthetics/management and lifestyle. Most of the facets behind agreeableness related positively to co-workers and altruism, while the same facets related negatively to income. The facets behind openness related negatively to aesthetics/management, whereas the majority of its facets related positively to altruism.

Table 3 Means, Standard Deviations, Cronbach’s Alpha and Inter-correlations for the Extrinsic Work Values

Note. All correlations are significant at the p < 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Studying the inter-correlations between the personality facets behind the five factors of the NPT and gender, age, and educational level background variables show that five of the six facets of the extraversion factor (warmth, gregariousness, activity, excitement seeking, and positive emotion) correlate negatively to age within a range of r = -.278 to r = -.130. The compliance facet of the agreeableness factor correlates positively to age (r = .268). Investigating the inter-correlations between the different work values and the gender, age, and educational level background variables show that two of the seven intrinsic work values and one of the seven extrinsic values correlate negatively to age (mental challenge, r = -.218, achievement r = -.161, and co-workers, r = -.157).

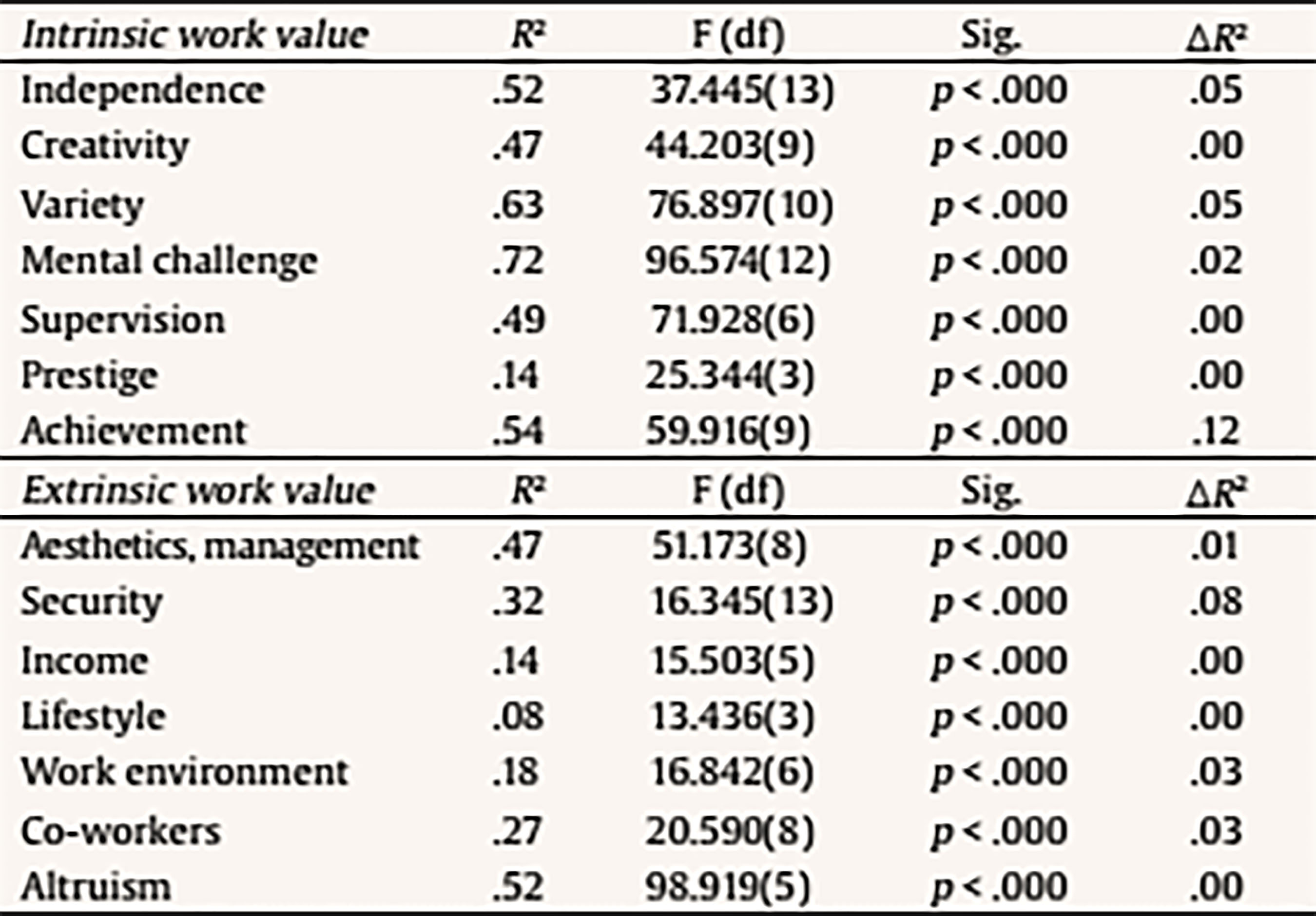

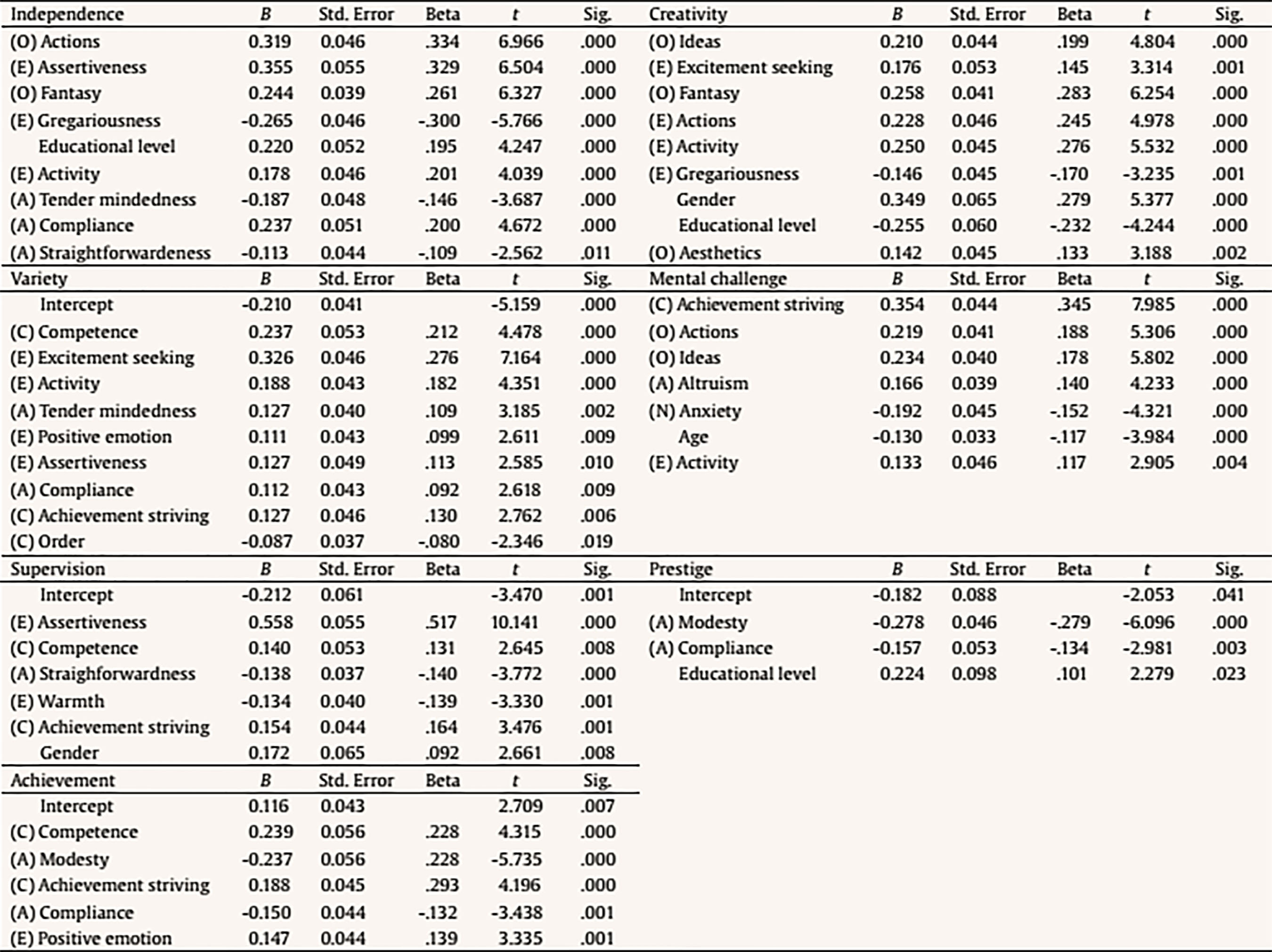

Table 4 gives the results of the model summary of the stepwise multiple linear regression analyses, predicting both the seven dependent intrinsic work values and the seven dependent extrinsic work values with the independent personality facets and the gender, educational level, and age background variables. The personality facets and the gender, educational level, and age background variables explained 14% to 70% with an average of 47% of the variance in intrinsic work values and 8% to 52% with an average of 28% of the variance in extrinsic work values.

Table 5 gives the results of the stepwise multiple linear regression analyses, predicting the seven dependent intrinsic work values with the independent personality facets and the gender, educational level, and age background variables. The variance in the intrinsic work value independence was explained by the facets of the agreeableness, openness, and extraversion factors. The variance in creativity was explained by the facets of the extraversion and openness factors. The variance in variety was mainly described by the facets of conscientiousness and extraversion. The variance in mental challenge was mainly explicated by the facets of openness. The variance in supervision was primarily explained by the facets of conscientiousness and extraversion. The variance in prestige was explicated by the facets of agreeableness. And achievement was primarily described by the facets of agreeableness and conscientiousness.

Table 5 Stepwise Multiple Linear Regression Analyses, Predicting the Intrinsic Work Values with the Background Variables and the Personality Facets

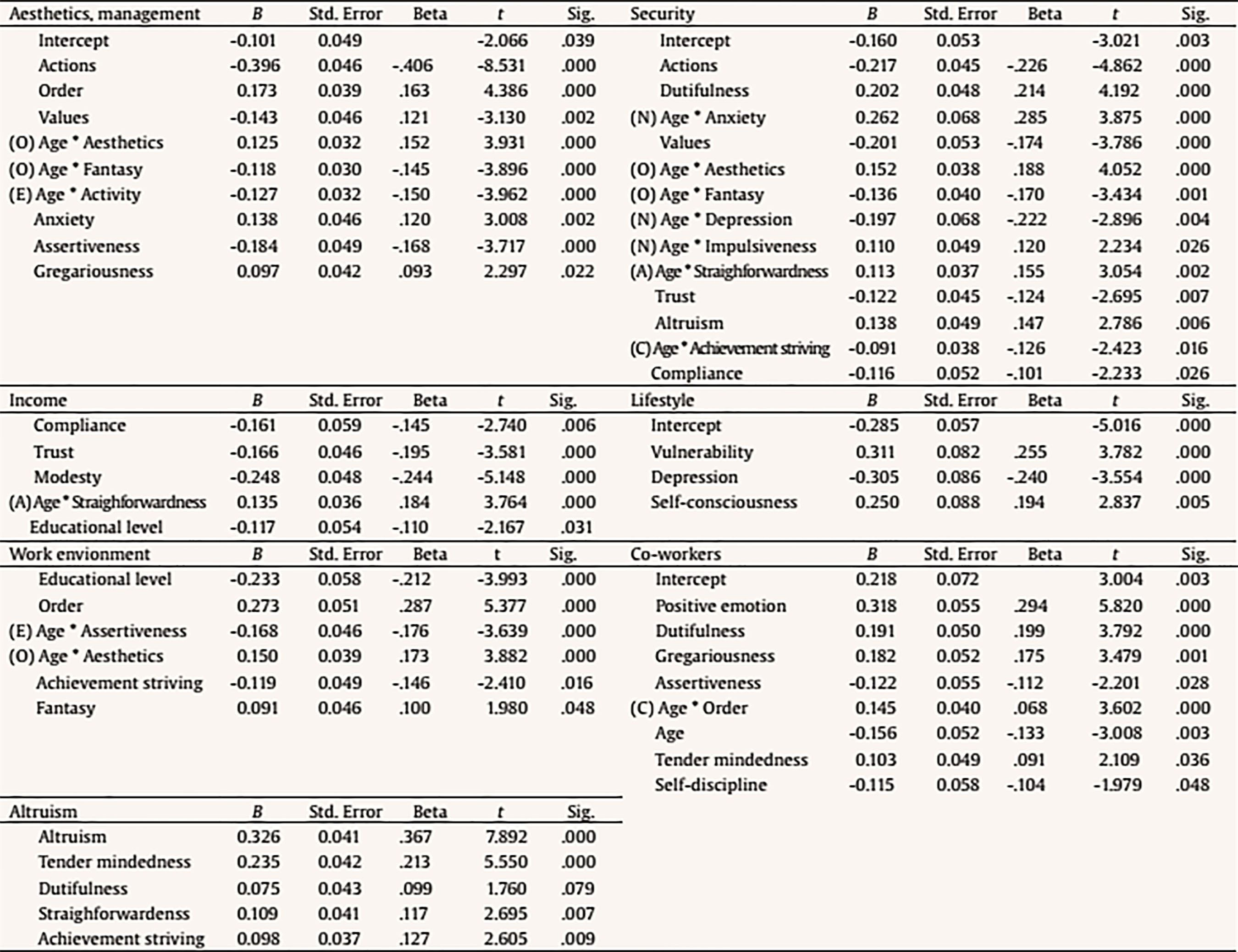

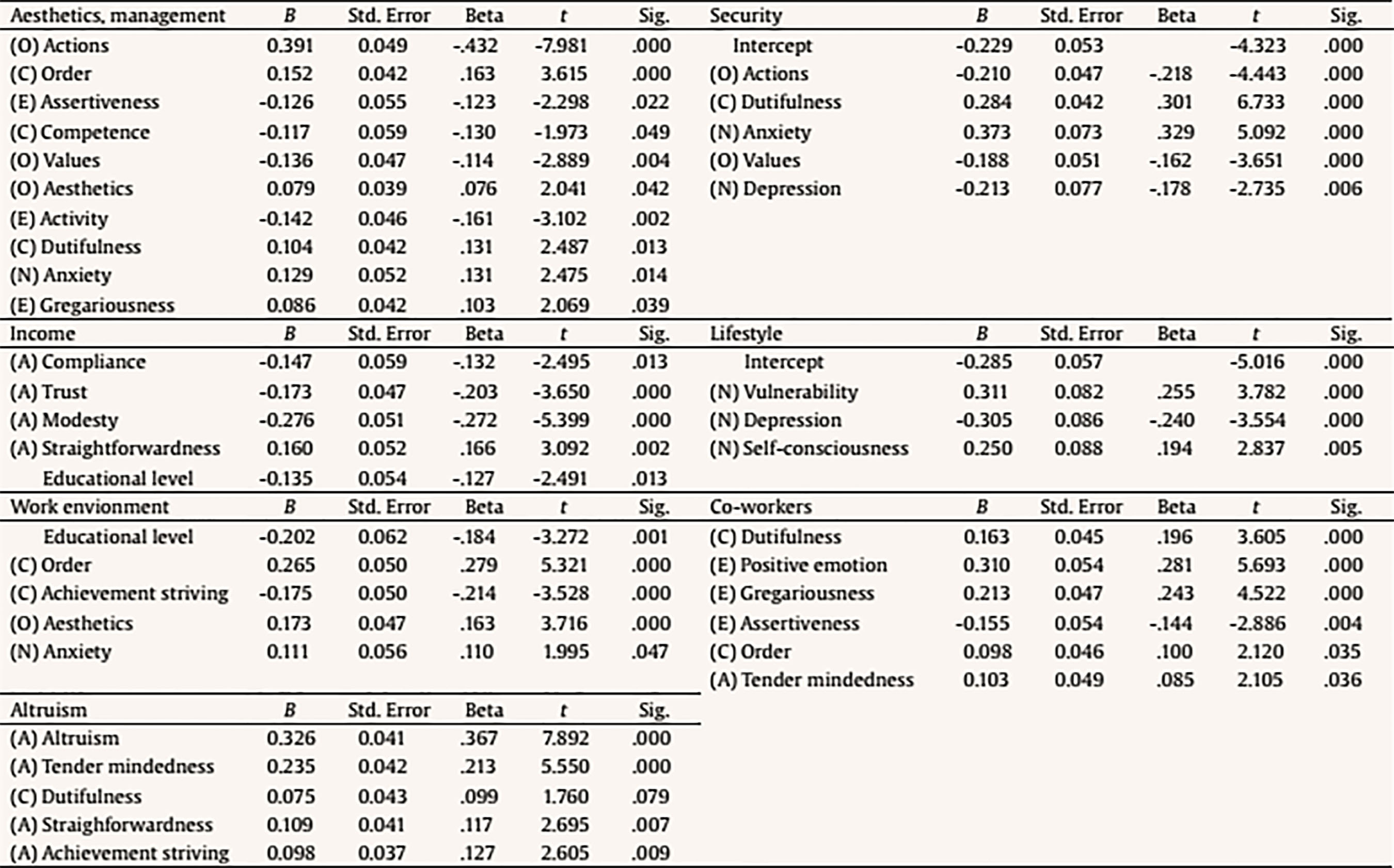

Table 6 gives the results of the stepwise multiple linear regression analyses, predicting the seven dependent extrinsic work values with the independent personality facets and the gender, educational level, and age background variables. The variance in the extrinsic aesthetics/management work value was mainly explained by the facets of the conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness factors. The variance in security was mainly explained by the facets of neuroticism and openness. The variance in income and altruism both were mainly explained by the facets of the agreeableness factor. The variance in lifestyle was described by the facets of neuroticism. The variance in work environment was primarily explicated by the facets of conscientiousness. And co-workers was mainly explained by the facets of conscientiousness and extraversion.

Table 6 Stepwise Multiple Linear Regression Analyses, Predicting the Extrinsic Work Values with the Background Variables and the Personality Facets

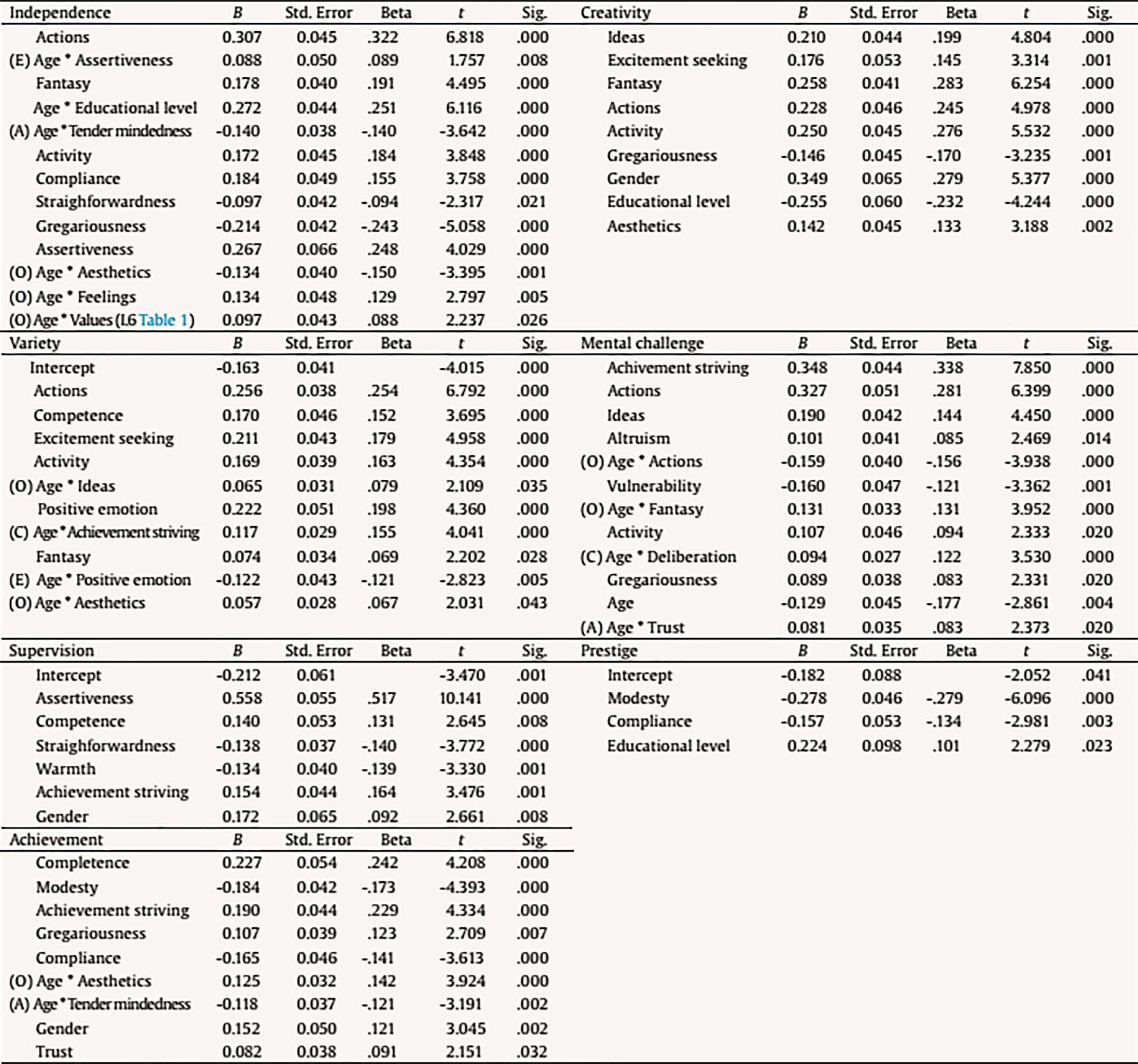

Table 7 gives the results of the model summary of the stepwise moderation analyses with multiple regression analysis, predicting the influence of age in the association between both the seven dependent intrinsic work values and the seven dependent extrinsic work values, the independent personality facets and two background variables, gender and educational level. For four of the seven intrinsic work values, the study found a moderating influence of age, explaining 2% to 12% of the variance. For four of the seven extrinsic work values, a moderating influence of age, explaining 1% to 8% of the variance, was found.

Table 8 gives the results of the model fit of the stepwise moderation analyses with multiple regression analyses, predicting the influence of age in the association between the seven dependent intrinsic work values, the independent personality facets and two background variables, gender and educational level. This study found for the intrinsic work value independence a negative interaction between age and tender mindedness (agreeableness), a positive interaction between age and assertiveness (extraversion), a negative interaction between age and aesthetics (openness) and a positive interaction between age and feelings and values (openness). For the variety intrinsic work value, this study found positive interactions between age and ideas (openness), between age and achievement striving (conscientiousness). A negative interaction was found between age and positive emotion (extraversion) and a positive interaction was found between age and aesthetics (openness). For the intrinsic work value mental challenge, this study found a negative interaction between age and actions (openness), and positive interactions between age and fantasy (openness), age and deliberation (conscientiousness), and age and trust (agreeableness). For the achievement intrinsic work value a positive interaction between age and aesthetics (openness), and a negative interaction between age and tender mindedness (agreeableness) was found.

Table 8 Stepwise Moderation Analyses with Multiple Linear Regression Analysis, Predicting the Influence of Age in the Association between Intrinsic Work Values, Personality Facets, and the Background Variables

Table 9 gives the results of the stepwise moderation analyses with multiple regression analyses, predicting the influence of age in the association between the seven dependent extrinsic work values, the independent personality facets and two background variables, gender and educational level. For the aesthetics/management extrinsic work value this study found a positive interaction between age and aesthetics (openness) and negative interactions between age and fantasy (openness) and between age and activity (extraversion). For the security extrinsic value, this study found positive interactions between age and anxiety (neuroticism) and between age and aesthetics (openness). Negative interactions were found between age and fantasy (openness) and between age and depression (neuroticism). Positive interactions were found between age and impulsiveness (neuroticism) and between age and straightforwardness (agreeableness). A negative interaction was found between age and achievement striving (conscientiousness). For the income intrinsic value a positive interaction between age and straightforwardness (agreeableness) was found. For the work environment extrinsic value, a negative interaction between age and assertiveness (extraversion), and a positive interaction between age and aesthetics (openness) was found. For the co-workers extrinsic work value a positive interaction was found between age and order (conscientiousness). The study demonstrated a significant moderating influence of age in the association between personality facets and nine of the 14 work values.

Conclusion

This study examined the role of age in the association between personality on a facet level and work values, differentiated in two clusters of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors. This study was conducted in the banking sector, that, following the financial crisis, was confronted with major changes in the way its employees were used to exert their jobs. The sector experienced directly the importance of selecting and bringing into action authentic and versatile employees from a long-term tenable and age-dependent approach.

Hypothesis 1a suggests that personality facets behind the extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness factors show stronger positive relations with intrinsic than with extrinsic work values factors. Hypothesis 1b suggests that personality facets behind the agreeableness and neuroticism show stronger positive relations with extrinsic than with intrinsic work values. The study found that the facets behind extraversion related positively to six of the seven intrinsic work values towards two of the seven extrinsic work values. The facets behind conscientiousness related positive to three of the intrinsic work values versus two of the extrinsic work values. The majority of the facets behind openness related positively to five of the seven intrinsic work values compared to one of the extrinsic work values. The facets of agreeableness related positively to three of the seven intrinsic as well as three of the seven extrinsic work values. The facets of neuroticism related positively to four of the seven extrinsic and none of the intrinsic work values. The personality facets and the gender, educational level, and age background variables explained on average 47% within a range of 14% to 70% of the variance of intrinsic work values. The personality facets and the gender, educational level, and age background variables explained on average 28% within a range of 8% to 52% of the variance in extrinsic work values. Therefore, hypothesis 1a is supported. With the exception of agreeableness, hypothesis 1b is supported as well.

Hypothesis 2a suggests that people until the age of 35 years score higher on the personality facets of the extraversion, neuroticism, and openness factors than people of 45 years and older. This study shows an effect for six of the seven facets of the extraversion factor. Therefore, hypothesis 2a is supported for the facets of the extraversion factor. Hypothesis 2b suggests that people of 45 years and older score higher on the personality facets of the agreeableness and conscientiousness factors than people until the age of 35 years. This study only shows an effect for one of the six facets of the agreeableness factor. Therefore, hypothesis 2b is slightly supported for the facets of the agreeableness factor.

Hypothesis 3a suggests that people until the age of 35 years score higher on intrinsic work values than people of 45 years and older. This study presents a higher score for people until the age of 35 years on the mental challenge and achievement intrinsic values. Therefore, hypothesis 3a is supported for two of the seven intrinsic work values. Hypothesis 3b suggests that people of 45 years and older score higher on the extrinsic work values than people until the age of 35 years. This study does not present significant higher scores for people of 45 years and older on extrinsic values. Contrary to what was expected, the study shows that people until the age of 35 years score higher on the co-workers extrinsic work value than people of 45 years and older. Therefore, hypothesis 3b is not supported.

Hypothesis 4a suggests that age influences the association between the personality facets of the extraversion, neuroticism, and openness factors and intrinsic work values in the sense that this association is stronger for people until the age of 35. This study shows that for this age group the concerning association is stronger for four of the seven intrinsic values (independence, variety, mental challenge, and achievement). Therefore, for four of the seven intrinsic work values, hypothesis 4a is supported. Hypothesis 4b suggests that age influences the association between the facets of the agreeableness and conscientiousness factors and extrinsic work values in the sense that this association is stronger for people of 45 years and older. For the income, co-workers, and security values, this study shows a positive interaction between an increasing age and facets of the agreeableness and conscientiousness factors. Therefore, for three of the seven extrinsic work values, hypothesis 4b is supported. Concluding, this study found a significant contribution of age to the association between personality facets and work values, differentiated in intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors.

Discussion

Earlier studies on the relationship between personality traits and work values mentioned the lack of agreement on which associations are stronger (Parks, 2007; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015). The present study further elucidated these ambiguities, taking into account the bandwith-fidelity dilemma (Cronbach & Gleser, 1965). This dilemma discusses the choice whether a careful measurement of a single narrowly defined variable or a more cursory exploration of many separate variables should be used in studying the personality domain. From both an empiric and a psychometric perspective, it is said that a more accurate and comprehensive picture of personality can be obtained from the use of global, overall measures of personality traits, like the five factors of the FFM (Ones & Viswesvaran, 1996). However, when the study aims to identify employee characteristics in personnel selection from a developmental perspective, they just plead for the use of narrower personality traits instead of the use of broader traits. Therefore, the present study chose to investigate its joint associations at a personality facet level instead of at a personality factor level. Next to that, work values were differentiated in intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors. The most remarkable inter-correlations between facets and values show that just like the findings of Berings et al. (2004), Furnham et al. (2005), Parks (2007), Bruyninckx and Valkeneers (2010), Bipp (2010), and Parks-Leduc et al. (2015), the facets behind extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness are positively related to primarily intrinsic work values. The present study adds to this confirmation that the same facets relate positive to two extrinsic work values, co-workers and altruism, as well. This strengthens the existing debate whether these two values might be more intrinsic than extrinsic in their nature. The facets behind neuroticism are positively related to only extrinsic work values. Studying the inter-correlations at a facet level also further clarifies the earlier contradictory outcomes on the agreeableness factor. The present study shows that the straightforwardness and modesty facets relate negatively to intrinsic work values, whereas its trust and altruism facets relate positively to intrinsic work values. Likewise, the facets behind agreeableness relate positively to the extrinsic altruism value. This suggests that being agreeable in a work context is sometimes because the helpful act itself is inherently rewarding. Every so often, the helpful act might be instrumental in bringing about desired outcomes such as rewards or the avoidance of punishment. Summarised, the different associations found in this study emphasize the importance of the interplay between personality facets and work values in building a long-term tenable fit between employee and organisation.

This study further shows that people until the age of 35 years score significantly higher on the facets behind extraversion and on the mental challenge and achievement intrinsic work values and on the co-workers extrinsic work value. The associations between the facets and values for this age group are strongest for the facets behind extraversion, neuroticism, openness, and the independence, variety, mental challenge, and achievement intrinsic work values. People of 45 years and older score slightly higher on the facets behind agreeableness. For this age group, the associations behind the facets behind agreeableness and conscientiousness and the income, co-workers, and security extrinsic work values are stronger. These findings confirm the earlier result of both Roberts, Walton, and Vliechtbauer (2006) and Costa & McCrae (2006), that extraversion declines with an increasing age. Besides, it approves the earlier noted assumptions on a decrease in intrinsic values and an increase in extrinsic values over time of, e.g., Rhodes (1983), Inglehart (1997), and Johnson (2001).

The present study gives a more detailed insight into the exact pattern of the moderating influence of age in the association between personality facets and work values. People until the age of 35 years old can be characterised by the aesthetics, actions, positive emotion, and tender mindedness personality facets, while seeking independence, variety, mental challenge, and achievement. People of 45 years and older can be described by the order, straightforwardness, and anxiety personality facets while looking for income, co-workers, and security. A theoretical explanation could be that older people have a slightly greater preference for tarring their own expertise within a clear structured and reward-driven environment, whereas younger people prefer to assert themselves towards their peers within a less regulated environment. In establishing both a long-term tenable and an age-specific fit between the employee and the organisation, the present study shows the importance of the role of age in the association between personality facets and work values.

Limitations

Before turning to the recommendations and implications of this study, there are some limitations to take into account. The first limitation concerns the cross-sectional design. The potential influence of a cohort effect in this type of design has been limited, because permission for the use of data was asked afterwards. This prevented a bias of social desirability aspects in the data collection procedure. However, as a consequence of this design, the associations found here rely on prior research and theoretical arguments. Without further longitudinal research, this cannot be fully ascertained. Second, the fact that this study only used self-reports to measure the variables might have led to a certain mono-method bias. Third, the present study investigated a Dutch sample, without examining the robustness of the findings on a second sample from another country or working background. On the other hand, diverse results of the present study were comparable with the cross cultural British and Greek findings of Furnham et al. (2005), as well as with the findings from earlier and different composed samples (e.g. Bipp, 2010; Parks-Leduc et al., 2015).

Recommendations and Implications

This study contributed to building both a long-term tenable and an age-specific fit between the employee and the organization by investigating the role of age in the association of personality traits on a facet level and work values, differentiated in two clusters of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation factors. However, since the present study only investigated a sample of bankers, future research is needed to generalise the results. For example, replicating this study within different cross-cultural samples might increase the reliability and validity of these outcomes. Longitudinal studies on the association between facets and values might contribute to ascertain the existing theoretical arguments of the tested associations. Further, to limit a possible mono-method bias, it might be useful to add interpersonal reports of presumed characteristics to the self-reports of personality. This may help to elucidate the influence of the self-image of the respondent, which, in turn, might be an indication for the amount of being versatile. Remarkable is that in the existing literature there are large differences in measuring work values. A third recommendation is to conduct and compare different studies that use the same set of personality facets and work values. This might elucidate the lack of clarity in the existing studies. An additional advantage could be that this will enlarge the insights in the exact role of age in the association between facets and values. Finally, it may be useful to replicate this study amongst various types of collaboration. Most studies, so far, have investigated samples of people, working in paid employment. It may be interesting to investigate whether the same effects will take place for self-employed people working on a freelance basis.

In sum, this study has shown that older people tend to prefer a clear structured and reward-driven environment in which they can lean on their expertise, whereas younger people desire a less regulated and development-driven environment in which they can assert themselves towards their peers. This implies, following the study of Roberts et al. (2008), the presence of a wider socialisation process, in which age is one of the determining variables of one’s life-stage. In studying this influence of life-stage, an operationalisation of the age factor might contribute to elucidating the effect of this socialisation process in the association between personality facets and work values. Whereas age on itself is seen as an index variable, a conceptual model of life-stage may consist of a combination of biological-, social-, and psychological elements of age, complemented with aspects of the self-image, the home situation, and biographic aspects of the career stage (Ornstein, Cron, & Slocum, 1989; Specht et al., 2014). Therefore, it is recommended that in a future building of a long-term tenable and an age-specific fit between the employee and the organisation, the influence of the wider concept of life-stage is taken into account. This more detailed insight in the influence of age from a wider life-stage perspective on the exact association between personality facets and work values might be useful for nowadays recruitment and selection procedures. This way of assessing might contribute to retaining the sustainable employability of both the young and the older worker, because a long-term tenable and an age-specific approach of the workforce stimulates each individual to be authentic and versatile in his or her personal, best fitting, way. Therewith, the present study may contribute to the debate of ageing in recruitment and selection policies and practices.