Introduction

What are the factors enabling an organization that is characterized by employees that have high workloads and who respect others’ rights, follow the rules and regulations (even if not overseen by supervisors), preclude conflicts, altruistically assist their colleagues, and do not complain about trivial issues? Could this state of affairs pervade real organizations?

The answer is that there are, indeed, many organizations striving to encourage these kinds of positive behaviors in the workplace (Chernyak-Hai & Rabenu, 2018). The employees’ actions comprise discretionary behavior, coined Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), which is neither formally recognized nor rewarded. In the increasingly dynamic and competitive environment in which organizations operate, OCB is considered a highly valuable contributor to the effective functioning of an organization. Notably, in recent years, there has been increasing interest in OCB recorded by several management scholars (e.g., Bogler & Somech, 2019; Oren et al., 2013; Turnipseed, 2018). According to Tziner and Sharoni (2014), since the year 2000, no fewer than four hundred articles on OCB and related constructs have been published by organizational researchers. Significantly, as we specify below, recent research has explored the way employees’ perceptions of their leaders influence their OCB behaviors (Dartey-Baah & Addo, 2019; Harris et al., 2014; Khalili, 2017). More specifically, this research has focused on and recognized the significance of understanding the role of employees’ “cognitive-motivational stimuli”, i.e., the implications of employees’ perceptions and attributions on their decisions to engage or not to engage in OCB (e.g., Bowler et al., 2019; Rioux & Penner, 2001; Spitzmuller et al., 2008). In our view, however, to date, this venue has been insufficiently explored, and, consequently, the theme constitutes a major thread of our research.

Following recent studies on the impact of employees’ perceptions of their relationship with the leader on pro-social behaviors associated with OCB (Bowler et al., 2019; Lapierre & Hackett, 2007), we aimed to advance research focusing on the implications of employees’ attributions on workplace behavior (e.g., Lee & Barnes, 2020; Martinko & Mackey, 2019; Seele & Eberl, 2020), by exploring the way employees’ inferred reasons for their managers’ decisions associate with their OCB. Given past findings indicating low OCB manifestations in case of low-quality leader-member exchange (Bowler et al., 2019), we sought to further investigate the potential negative implication of unfavorable attributions made by the employees in relation to their immediate supervisors’ decisions on their citizenship behavior. Specifically, drawing from the literature on attribution-affect-action relationships (Weiner, 1980, 2006), we examined whether employees’ causal attributions of leaders’ workplace decisions associated with their emotional state, and how this emotional state related to their reported OCB.

Furthermore, work context and personality factors may also influence attempts to discern managerial decisions and their employees’ motivations to display OCB (e.g., Bergeron et al., 2014; Chernyak-Hai & Tziner, 2012; Liu et al., 2019; Neale, 2019; Rappon et al., 2018). Accordingly, we investigated additional workplace factors as “perceived” by the employees that may interact with attributions on employees’ engagement in OCB. In this vein (as detailed below), we tested (1) the contribution of perceived organizational ethical climate to the relationship between employees’ attributions and emotions, (2) the effect of perceived ethical climate interacted with employees’ attributions, and (3) the contribution of personal levels of self-enhancement.

By examining the way inferenced reasons for managerial acts and decisions relate to employees’ OCB, the underlying emotions, and the way attributions interact with perceptions of workplace environment and personal dispositions, we aim to achieve several goals. First, we contribute to the research on cognitive-motivational antecedents of OCB (e.g., Bowler et al., 2019; Lapierre & Hackett, 2007; Spitzmuller et al., 2008). Particularly, we employ a well-established model of attribution-affect-action relationships (Weiner, 1980, 2006; detailed below) to understand implications of employees’ attributions on workplace behavior, while focusing on their understanding of those whom they perceive as responsible for their working conditions – their direct supervisors. In other words, we emphasize the need to explore not only what the manager does, but also the “attributions” that the employee has over what the manager does. Second, as we are aware that human behavior is also affected by personal and broader social context variables, we explore the contribution of factors that were recently shown to have particular implications on OCB – self-enhancement and perceived ethical climate (as explained (below) –, and the way they contribute to the examined attributions-emotion-OCB link. Therefore, the novelty of the present study lies both in unveiling the negative implications of inferred causes of managerial decisions on OCB via effects on employees’ affective state, and in understanding the moderating role of personal motives and organizational climate.

In what follows, we introduce, first, past research findings on the associations between employee-manager relations and OCB. Next, we address the tenets of the attribution-affect-action theory and its relevance to OCB. Finally, we present the rationale for the predicted moderations by perceived organizational ethical climate and self-enhancement.

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) and Employee-Manager Relationships

The most common definition of OCB is “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and in the aggregate promotes the efficient and effective functioning of the organization” (Organ et al., 2006, p. 3). Specifically, OCB has been characterized by behavioral structures that include readiness to provide help to other members at the workplace without expecting subsequent rewards (altruism); task-related activities that go beyond role requirements (conscientiousness); positive involvement in the life of the organization (civic virtue); preventing workplace conflicts (courtesy); and tolerating inconveniences without complaining (sportsmanship) (Organ, 1988; Podsakoff et al., 2009; Srivastava & Saldanha, 2008).

Notably, it was found that supervisors’ leadership style may encourage OCB via its implications for employees’ work engagement (Dartey-Baah & Addo, 2019; Khalili, 2017). This finding has been interpreted in the context of the leader-member exchange (LMX) model, extensively used in past studies to reflect the quality of the relations between superiors and subordinates at the workplace (see Fein et al., 2020). Specifically, high-level LMX was found to predict employees’ sense of empowerment, cooperation, loyalty, and OCB (e.g., Harris et al., 2014; Ilies et al., 2007; Tziner et al., 2012).

Recent research has further addressed the implications of employee-manager relationships for OCB. For example, De Ruiter et al. (2016) found that LMX mediates the relationship between “breach of manager obligations” and “coworker-directed citizenship behavior” and OCB when facing organizational change. Other studies have indicated that employee-manager relationships have a positive effect on employees’ OCB when the relationships are characterized by benevolence and moral leadership (Tang & Naumann, 2015) and low, rather than high, levels of power distance (Anand et al., 2018). In the present study, we adopted a different perspective, namely, without undermining the importance of LMX for employees’ workplace behavior, we investigate implications of employees’ attributions of their managers’ workplace decisions – what employees “believe” to be reasons for their supervisors’ considerations. Specifically, based on the attribution-affect-action model (Weiner, 1980, 2006) described below, we suggest that: (1) insight into employees’ inferences regarding their superiors’ decisions and (2) a grasp of employees’ emotional states, would enable management to generate significant impacts on their employees’ citizenship behaviors.

The Attribution-Affect-Action Model

The attribution-affect-action model is part of the attribution theory of motivation proposed by Weiner (1980, 2006, 2012) to explain the psychological process involved in how we associate causes with our own and others’ personal states and decisions. According to Weiner (1988), we infer causes along dimensions of locus (internal versus external), controllability, and stability. For instance, following Weiner, an internal cause such as personal ability may be uncontrollable and stable or, like effort, controllable and unstable. Similarly, whereas task difficulty is an external, uncontrollable, and stable cause, others’ affection is external, (relatively) controllable, and unstable. Note that when a certain act is attributed to an internal and controllable cause, people tend to see it more as an indication of free will relatively to an internal and uncontrollable cause (Weiner, 2006). Accordingly, one may expect that the correlation between the inferred internal causes might not be high, although positive. In contrast, higher attribution to internal factors is supposed to be mirrored by lower attribution to external causes (see, for example, Nadler & Chernyak-Hai, 2014). In the present research, we focused on internal attributions of managers’ decisions, as factors that are perceived as characteristic of an employee’s supervisor. Our premise is that both lack of ability to “take care” of one’s employees and lack of motivation to do so, predict employees’ negative emotional reactions and unwillingness to engage in OCB.

Furthermore, Weiner’s attribution theory distinguishes between the role of thoughts and feelings in determining action (Weiner, 1980, 2006). A basic supposition is that attributions influence the way people derive conclusions about the observed actor’s characteristics and intentions, because these perceptions affect the observer’s emotions and subsequent actions. Specifically, numerous studies have shown that unfavorable attributions – e.g., attribution of negative states to causes that are internally controllable by persons – elicit anger or disgust, and discourage pro-social behavior (e.g., Marjanovic et al., 2009; Mosher & Danoff-Burg, 2008; Reisenzein, 2014; Reisenzein & Rudolph, 2018; Weiner 1980, 2018).

Employees’ Attributions and OCB

Scholars have argued that attribution theory has been underutilized in organizational research (e.g., Harvey et al., 2014). However, in recent years, meta-analyses have indicated that attributions are an important source of information in understanding individual cognitive processes that have implications for “organizational” outcomes (Harvey et al., 2014). Thus, more recent research, for instance, has indicated the ways attributions are related to different aspects of workplace behavior (see Martinko & Mackey, 2019). These modes include moral behavior (Lee & Barnes, 2020; Martinko, 2004), knowledge sharing (Lekhawipat et al., 2018), confrontation and withdrawal (Seele & Eberl, 2020), and antisocial and pro-social behavior (Mulder et al., 2016). Another recent study (Matta et al., 2020) has further indicated that employees’ attributions of supervisors’ motives affect employees’ perceptions of justice and supervisor-directed citizenship behavior.

However, research on associations between attributions of leaders’ functioning and employees’ OCB is scarce. One study regarding relationships between perceived supervisors’ misbehavior and OCB indicates that negative relations were found between supervisors’ moral disengagement and employees’ OCB (Bonner et al., 2016). Conversely, in another investigation, employees’ perceptions of their leaders as actively listening to them impacted positively on their affect and OCB (Lloyd et al., 2015).

In the current research, we sought to extend knowledge concerning the ways by which employees’ “attributions” of their supervisors’ decisions may “undermine” the employees opting for OCB. More specifically, we focus on attributions bearing on a perceived supervisor’s incapability and lack of motivation to benefit her/his employees and, therefore, negative implications on employees’ affective state and manifestations of citizenship behavior. Further, it is important to note that past research has shown the importance of employees’ adverse emotions following negative exchange with their leaders in reducing positive and facilitating negative workplace behaviors (see Supriyanto et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). For example, abusive supervision was found to reduce employees’ OCB, and these findings were addressed based on the notion of adhering to the norm of (negative) reciprocity (Zhang et al., 2019). In a different study, a leader’s narcissism was found to negatively affect employees’ OCB through hindrance stress (Li & Zhang, 2018).

Accordingly, following the tenets of the attribution-affect-action model, we predicted that employees who make negative internal attributions of their supervisors’ decisions – e.g., that they typically lack motivation to promote their employees or that their decision-making is impulsive and mood-affected – experience “adverse” emotions at their workplace, and are accordingly less engaged in OCB. We thus hypothesize that:

H1: The effect of employees’ negative attributions on OCB is mediated by negative affect, so that higher levels of negative attributions predict higher levels of negative emotions, and higher levels of negative emotions predict less OCB.

Organizational Ethical Climate (OEC) and OCB

One of the most researched antecedents of OCB is organizational climate and, particularly, organizational ethical climate – OEC (e.g., Çavu & Develi, 2017; Pagliaro et al., 2018; Shin, 2012; Tziner et al., 2015). OEC encompasses organizational members’ perception of moral obligations and the way ethical issues should be handled at the workplace (e.g., Chernyak-Hai & Tziner, 2014; Tziner et al., 2015). Specifically, research has indicated that OEC is significantly associated with OCB (Navid Hamidi et al., 2017) and mediates the effects of leadership quality on OCB (Zehir et al., 2014). Importantly for the present study, past research differentiated among three aspects of OEC, reflective of ethical standards. These are maximization of self-interest, profit and efficiency (i.e., egoism), concern for the well-being of others, friendship and social responsibility (i.e., benevolence), and adherence to standards, rules, and personal morality (i.e., principle) (Cullen et al., 1993; Victor & Cullen, 1988). These dimensions were supported in a meta-analysis (Martin & Cullen, 2006), and found to predict workplace attitudes and behavior (e.g., Choe et al., 2017; Nedkovski et al., 2017; Sen & Rathore, 2018). In the present research, we purported to explore the way perceived OEC moderates the relationships between attributions of managerial decisions, employees’ emotions, and OCB, and whether the associations between employees’ perceptions of the three OEC facets and OCB are explained by their interactions with employees’ attributions. As mentioned earlier, while in the present research attributions constitute perceptions of causes underlying direct supervisors’ decisions relevant to employees’ well-being and success (i.e., having benefits and being promoted), perceived OEC reflects employees’ judgements of the overall organizational context. Therefore, perceived OEC may be independent of attributions made over behavior of a certain supervisor, and yet moderate their implications on employees’ behavior. For example, one may assume that when OEC emphasizes egoistic self-promotion at the expense of one’s colleagues, such an atmosphere would reduce OCB. Add to this situation high negative attribution of leaders’ behavior and the chances of OCB manifestations would be very low. However, if similar perceived OEC prevails when the employees do not hold negative attributions towards their supervisors, and infer mutual interests, there might be higher probability for OCB (see Waismel-Manor et al., 2010). Notably, we posited that OEC “buffers” the negative implications of attributions on employees’ emotions, so that employees holding strong (i.e., high) levels of one of the three OEC dimensions (i.e., egoism, principles, and benevolence) would be less affected by attributions’ emotional implications. In other words, we expected a compensation effect between perceived organizational- and personal-level factors affecting OCB, namely, employees associate the negative behavior of their managers with a perceived “organizational atmosphere” in which managers operate when inferring individual factors related to managers’ decisions (see Figure 1 for overall research model). To explore this prediction, we tested the interactions of each of the three OEC dimensions in predicting employees’ emotions and OCB. We thus hypothesized that:

H2: Perceived OEC moderates the indirect effect of employees’ negative attributions on OCB, so that the effect of attributions on employees’ affect (and thus on OCB) is attenuated, given high levels of either Egoism-, Principles-, or Benevolence-OEC.

Furthermore, we tested the interaction effect between perceived OEC and employees’ attributions on OCB to explore whether OEC perceptions positively predicted OCB depending on the level of negative attributions of managerial decisions. As explained above, attributions of a supervisor’s decisions and perceived OEC may interact in their effects on OCB. Therefore, we may also expect that employees’ holding significantly negative impressions of their leaders would be led by these impressions in their behavior beyond favorably perceived OEC dimensions. Accordingly, we expected that high levels of negative attributions would attenuate the relationship between perceived OEC and OCB (i.e., attributions may also function as moderators). We thus hypothesized that:

H3: Attributions moderate the effect of OEC on OCB, so that the effect of perceived OEC (either Egoism-, Principles-, or Benevolence-OEC) on OCB is attenuated, given the high levels of negative attributions.

Self-enhancement and OCB

Finally, we delved into the effect of an additional moderator, namely, self-enhancement. Research has shown that individual values have significant implications on organizational behavior (e.g., Chernyak-Hai & Tziner, 2016; Sagiv & Schwartz, 2007; Wang et al., 2011). The most comprehensive, empirically supported theory of personal values is Schwartz’s (1992, 1994, 2006) theory of values outlining ten fundamental human values arranged in a circular structure and opposing categories, so that pursuing the attainment of values in one of the opposing categories hinders the fulfillment of the other (Sagiv, 2011). Self-enhancement is one of the values that is egoistic in its orientation; it reflects aspirations of achievement (i.e., success through demonstrating competence) and power (i.e., status, prestige, and dominance over people and resources) (Schwartz, 1992, 1994). Of interest, Urien and Kilbourne (2011) recorded that self-enhancement interacts with values of generativity (i.e., concern for the environment), values that were traditionally addressed as contrary to egoistic concerns. In their investigation, the researchers revealed that individuals characterized by high levels of both self-enhancement and generativity are ready to consider their environment and act responsibly (Urien & Kilbourne, 2011). Also, although past research pointed to positive relationships between the pro-social personal values of self-transcendence (e.g., benevolence) and openness to change (e.g., self-direction) and OCB (Arthaud-Day et al., 2012; Seppälä et al., 2012), research has also indicated that self-enhancement positively predicts OCB (e.g., Arthaud-Day et al., 2012; Bolino et al., 2006; Rioux & Penner, 2001). Accordingly, it has been suggested that OCB motives are not necessarily pro-social and altruistic, but may follow self-promotion considerations that, for example, characterize impression management (Arthaud-Day et al., 2012; Bolino et al., 2013).

As mentioned earlier, human behavior is frequently affected by both personal and broader social context variables. Our focus on the personal characteristic of self-enhancement follows past findings on self-promotion considerations in OCB. Particularly, we suggest that when accessing implications of a social context variable indicative of perceived organizational climate on OCB, employees’ self-enhancement considerations are an important factor to be explored as a potential moderator in this relationship. Therefore, in the present investigation we opted to incorporate employees’ self-enhancement as a moderator of the relationship between OEC and OCB, as this value is tied to self-other considerations and relevant to both OCB and OEC. Although personal and organizational values may or may not be congruent (e.g., Ostroff et al., 2005; Posner, 2010; Schuh et al., 2018), values’ congruence was shown to be a significant factor in both employees’ and organizational functioning (Vveinhardt & Gulbovait, 2016). In the current study, we posited that individual adherence to self-enhancement may be at odds with moral orientation towards organizational laws and codes – the “principle” dimension – in a way that diminishes the manifestation of the acquiescence to organizational norms on OCB (see Figure 1 below). On the other hand, given the aforementioned past findings on the relations between personal values and OCB, we did not expect similar effects of self-enhancement on egoism- and benevolence OEC dimensions, since both types may serve self-promotion motivation to engage in OCB. We thus hypothesize that:

H4: Self-enhancement moderates the effect of OEC on OCB, so that the effect of principle-OEC on OCB is attenuated, given high levels of self-enhancement.

Overview of Studies

We tested the hypotheses in two consecutive studies. Study 1 examined the attribution-affect-action model, where attributions of managerial decisions predict OCB via workplace emotions, and this mediation is moderated by perceived OEC. In addition, we examined OEC perceptions’ implications for OCB when interacted with attributions (hypotheses H1-H3). Study 2 explored further whether the relationship between OEC perceptions and OCB is moderated by attributions (H3) and self-enhancement (H4).

The same procedures were employed for each of the two studies. The studies were conducted with convenience samples of working adults, sampled individually upon the research assistants’ invitation.1 Participants were told that the purpose of the studies was to explore employees’ attitudes, emotions, and behaviors at the workplace. Informed consent for collection of the data and using it for the present research purposes was obtained; both studies complied with ethical standards involving human participants. The studies employed traditional self-report techniques and, except for attributions (as explained in the Method section of Study 1), used existing scales to measure the key variables. Finally, at the end of each study, participants were thanked. Debriefing was implemented upon completion of the questionnaires.

Study 1

Method

Participants. 341 Israeli employees (194 women, 147 men) from the telecommunication sector volunteered to participate in the study (Mage = 38.52, SD = 9.43). As part of completing basic socio-demographic items, 55.1% of the employees stated that they were married, 31.4% were single, 13.2% were divorced, and one participant was widowed; 34.3% reported job tenure of 0-5 years, 24% were employed for 6-10 years, 12.9% had tenure of 11-15 years, and 28.7% had been employed for 16 years and above.

Measures

Causal attributions of managerial decisions were gauged according to Weiner’s (2006) attributional analysis conceptualization and previous research methodology (Nadler & Chernyak-Hai, 2014). As mentioned earlier, since we were interested in examining employees’ inferences of their leader’s intentions and characteristics, all the attributions were internal. Specifically, four attributions were formulated varying along the dimensions of controllability and stability (see Table 1), rated on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree) (M = 3.47, SD = 0.93). Participants were asked to refer to their direct supervisor’s decisions related to work issues, and indicate the degree to which they thought these decisions were (mostly) influenced by each of the following four causes: (1) typical lack of motivation to help/benefit the employees, (2) general lack of ability to help/benefit the employees, (3) “coldness” – lack of personal approach to employees –, and (4) “moods” – impulsiveness. We combined the four items to serve as a single index of negative attributions (α = .56).

Table 1. Causal Attributions of Managerial Decisions (Study 1)

Note. 1This item has a low loading on the overall “attributions” factor, as opposed to the other three, but was not removed, in order to incorporate its psychometric and theoretical information.

OEC was assessed using the 26-item ethical climate questionnaire (ECQ; Cullen et al., 1993; see also Chernyak-Hai & Tziner, 2014), measuring employees’ perceptions of their organization ethical criteria. The items were presented on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree); e.g., “What is best for everyone in the company is the major consideration here” (benevolence OEC dimension); “In this company, the first consideration is whether a decision violates any law” (principle OEC dimension); “The major responsibility for people in this company is to consider efficiency first” (egoism OEC dimension). Following the hypotheses, we used three overarching dimensions as suggested by Victor and Cullen (1988)2, namely: “Egoism” – items indicative of maximization of self-interest (M = 3.77, SD = 0.67, α = .66), “Principle” – adherence to standards and rules (M = 3.57, SD = 0.75, α = .74); and “Benevolence” – concern for the well-being of others (M = 3.63, SD = 0.77, α = .80).

OCB was measured using the OCB Checklist (OCB-C; Fox & Spector, 2011), where participants rated 20 items on a 6-point scale (1 = never, 6 = always) representing the degree to which they engaged in OCB in their present workplace; e.g., “Took time to advise, coach, or mentor a co-worker”; “Volunteered for extra work assignments” (M = 3.70, SD = 0.77, α = .88).

Negative emotions were gauged by a 10-item measure (Emotion Checklist; Djikic et al., 2009). Participants rated on a 6-point scale (1 = the least intensity I’ve ever experienced, 6 = the most intensity I’ve ever experienced) the intensity of the following experienced emotions while interacting with their supervisor: sadness, anxiety, happiness, boredom, anger, fearfulness, contentment, excitement, unsettledness, and awe. The scores of the positive emotions (i.e., happiness, contentment, excitement, and awe) were reverse-coded to obtain a single measure of negative affectivity (M = 3.04, SD = 0.82, α = .75).

Control variables. In our analyses, we controlled for the effects of gender, age, tenure, and marital status. The obtained results persisted when controlling for these variables.

Common-method bias. Relying on the same participants for assessments of all study variables may raise the risk of common method variance (CMV). Thus, we tested Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The single factor that emerged from the analysis accounted for only 17.87% of the explained variance. While this result does not completely rule out the possibility of same-source bias (i.e., CMV), according to Podsakoff et al. (2003) less than 50% (R2 < .50) of the explained variance accounted for by the first emerging factor indicates that common-method bias is an unlikely explanation of the findings.

Results

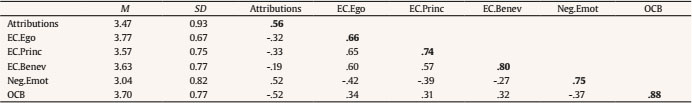

First, zero-order Pearson correlations were calculated, to observe the inter-correlations among the variables in the research, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Zero-order Bivariate Correlations with Reliability Coefficients (bolded) on the Diagonal (Study 1)

Note. EC.Ego = Ethical Climate’s Egoism dimension; EC.Princ = Ethical Climate’s Principle dimension. EC.Benev = Ethical Climate’s Benevolence dimension; Neg.Emot = negative emotions. OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors.All of the correlations are significant at ***p < .001.

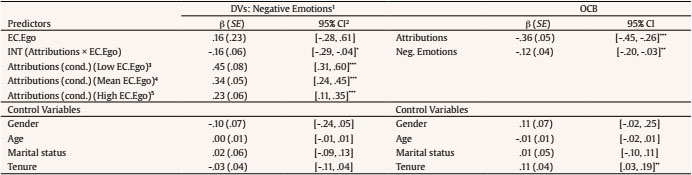

To test the attribution-affect-action model where attributions of managerial decisions predict OCB via emotions and the attributions-emotions link is moderated by OEC (H1-H3), we employed Hayes’ (2017) PROCESS 3.3 macro (Model 7). In this analysis, an index of negative attributions of managerial decisions was the predictor, OCB was the dependent variable, negative emotions measure was the mediator, and perceived ethical climate was the moderator.

The results indicated that negative emotions mediate the relationship between attributions and OCB. The index of moderated-mediation is .019, SE = .01, 95% CI [.01, .05] and, as such, the indirect effect of attributions on OCB via emotions is to be understood through conditioning. Specifically, the indirect effect diminishes in strength as the moderator levels are higher: (1) when the Egoism is “low”, the indirect “estimate” = -.05, SE = .02, 95% CI [-.11, -.01]; (2) when the Egoism is “mean”, the indirect “estimate” = -.04, SE = .02, 95% CI [-.08, -.01]; and (3) when the Egoism is “high”, the indirect “estimate” = -.03, SE = .01, 95% CI [-.05, -.01] (see also Table 3).

Table 3. Moderated-Mediation Analysis with Egoism Ethical Climate Dimension (Study 1)

Note. DV = dependent variable; EC.Ego = Ethical Climate’s Egoism dimension; OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors; Neg. Emotions = negative emotions; INT = interaction effect; Cond. = conditional effect; 1Negative Emotions = the mediator variable in the model (depicted as a DV in the regression path analyses only); 295% CI with 5,000 resampling via bias-corrected bootstrapping; 3Low = -1 SD from the mean; 4Mean = 0 SD from the mean; 4High = +1 SD from the mean.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Moreover, the moderation effect (attributions × Egoism interaction effect on emotions) is significant, β = -.16, SE = .06, p = .011 (see also Figure 2). The interpretation of this interaction is depicted in Figure 3 (i.e., in higher levels of egoism ethical climate, the negative association between attributions and negative emotions diminishes).

Note. OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 2. Combined Path Diagram of Three Moderated-Mediation Analyses in Predicting OCB (with standardized coefficients).

Furthermore, similar results were obtained with the Principle ethical climate dimension. The index of moderated-mediation is .025, SE = .01, 95% CI [.01, .05]. The indirect effect diminishes in strength as moderator levels are higher: (1) when the Principle scores are “low”, the indirect “estimate” = -.06, SE = .03, 95% CI [-.12, -.02]; (2) when the Principle scores are “mean”, the indirect “estimate” = -.04, SE = .02, 95% CI [-.08, -.01]; and (3) when the Principle scores are “high”, the indirect “estimate” = -.02, SE = .01, 95% CI [-.05, -.01] (see Table 4).

Table 4. Moderated-Mediation Analysis with Principle Ethical Climate Dimension (Study 1)

Note. EC.Princ = Ethical Climate’s Principle dimension; OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors; Neg. Emotions = negative emotions; INT = interaction effect; Cond. = conditional effect. 1Negative Emotions = the mediator variable in the model (depicted as a DV in the regression path analyses only); 295% CI with 5,000 resampling via bias-corrected bootstrapping; 3Low = -1 SD from the mean; 4Mean = 0 SD from the mean; 5High = +1 SD from the mean.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The moderation effect (attributions × Principle interaction effect on emotions) was also significant, β = -.22, SE = .05, p = .000 (see also Figure 2). The interpretation of this interaction is depicted in Figure 4 (i.e., in higher levels of the principle ethical climate, the negative association between attributions and negative emotions diminishes).

Finally, in contrast to the moderation obtained with the Egoism and Principle ethical climate dimensions, the index of moderated-mediation with Benevolence dimension as a moderator is .004, SE = .01, 95% CI [-.01, .02], indicating that the indirect effect of attributions on emotions is not conditioned by the Benevolence ethical climate (see Table 5). In addition, the moderation effect (attributions × Benevolence interaction) on emotions is non-significant, β = -.04, SE = .05, p = .492 (see also Figure 2. Also, see Figures 1 and 2 for combined path diagram of the moderated-mediation analyses).

Table 5. Moderated-Mediation Analysis with Benevolence Ethical Climate Dimension (Study 1)

Note. EC.Benev = Ethical Climate’s Benevolence dimension; OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors; 1Neg. Emotions = negative emotions; INT = interaction effect; Direct = non-conditional (direct) effect; 1Negative Emotions = the mediator variable in the model (depicted as a DV in the regression path analyses only); 295% CI with 5,000 resampling via bias-corrected bootstrapping.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Study 2

Method

Participants. 389 Israeli employees (203 women, 186 men) from the electrical and construction contractor sectors volunteered to participate in the study (Mage = 39.76, SD = 11.19). As part of completing basic socio-demographic items, 67.2% of the employees stated that they were married, 24.7% were single, 7.8% were divorced, and one participant was widowed; 15.4% reported job tenure of 0-5 years, 34.1% were employed for 6-10 years, 29.3% had tenure of 11-15 years, and 21.2% were employed for 16 years and above.

Measures

Causal attributions of managerial decisions were assessed similarly to Study 1. The participants answered four internal attributions of their direct supervisor’s decisions related to work issues, rated on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). As in Study 1, we combined the four items to serve as a single index of negative attributions (α =.79, M = 3.06, SD = 1.12).

OEC was measured similarly to Study 1 (26-item ethical climate questionnaire – ECQ; Cullen et al., 1993), measuring employees’ perceptions of their organization ethical moral climate, on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). Here, also, we used three overarching dimensions: Egoism (M = 3.84, SD = 0,54, α = .68); Principle (M = 3.98, SD = 0,65, α = .75); and Benevolence (M = 3.88, SD = 0,73, α = .84).

OCB. We used the OCB Checklist (OCB-C; Fox & Spector, 2011), similarly to Study 1, where participants indicated their answers on a 6-point scale (1 = never, 6 = always) (M = 3.99, SD = 0.87, α = .90).

Self-enhancement. To measure participants’ levels of self-enhancement, we employed a 4-item scale (Adaptive Disengagement Scale; Leitner et al., 2014; Leitner et al., 2013), using a 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree response scale. The measure assesses a person’s proclivity to self-enhance by dismissing negative feedback as a basis for self-worth. Items included: “I am good at shaking off failures and keeping a positive attitude”; “When I perform poorly at something, I do my best to keep a positive sense of self-esteem”; “I can adapt to almost any situation to maintain my self-esteem”; and “When bad things happen to me, I try not to feel bad about myself” (M = 3.68, SD = 1.20, α = .86).

Control variables. Similar to Study 1, we controlled for the effects of gender, age, tenure, and marital status. The obtained results persisted when controlling for these variables.

Common-method bias. Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003) revealed a single factor accountable for 17.87% of the explained variance, therefore indicating that common-method bias is an unlikely explanation of the findings.

Results

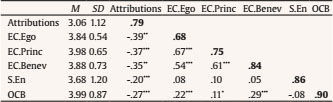

Zero-order Pearson correlations were calculated to observe the inter-correlations among the research variables (see Table 6).

Table 6. Zero-order Bivariate Correlations with Reliability Coefficients (bolded) on the Diagonal (Study 2)

Note. EC.Ego = Ethical Climate’s Egoism dimension; EC.Princ = Ethical Climate’s Principle dimension; EC.Benev = Ethical Climate’s Benevolence dimension; S.En = self-enhancement; OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

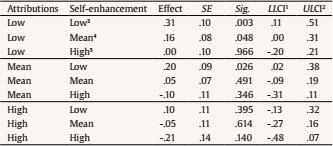

We used Hayes’ (2017) PROCESS 3.3 macro (Model 2) to test the dual-moderation model where attributions to managerial decisions and self-enhancement attenuate the effect of OEC on OCB (H3 and H4). In this analysis, OEC was the predictor, an index of negative attributions and self-enhancement were the moderators, and OCB was the dependent variable. The results indicated a positive effect of the Egoism dimension on OCB, β = 1.01, SE = .26, p = .000, and it was moderated only by attributions, β = -.15, SE = .06, p = .009, and not by self-enhancement, β = -.11, SE = .06, p = .056. Regardless of self-enhancement level, the higher levels of attributions, the positive association between Egoism ethical climate, and OCB diminishes (see Tables 7-8 and Figure 5).

Table 7. Moderation Analysis with Egoism Ethical Climate Dimension (Study 2)

Note. DV = dependent variable; OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors; INT = interaction effect; 195% CI with 5,000 resampling via bias-corrected bootstrapping.*p < .05, ***p < .001.

Table 8. Conditional Effects of the Focal Predictor (Egoism) on OCB at Values of the Moderators (Attributions and Self-enhancement, respectively) (Study 2)

Note. Analysis was based on 95% CI with 5,000 resampling via bias-corrected bootstrapping; 1LLCI = lower limit of CI; 2ULCI = upper limit of CI; 2low = -1 SD from the mean; 3mean = 0 SD from the mean; 4High = +1 SD from the mean.

Note. OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors.

Figure 5. Three-way Interaction Effect (Attributions × Egoism × Self-enhancement) on OCB.

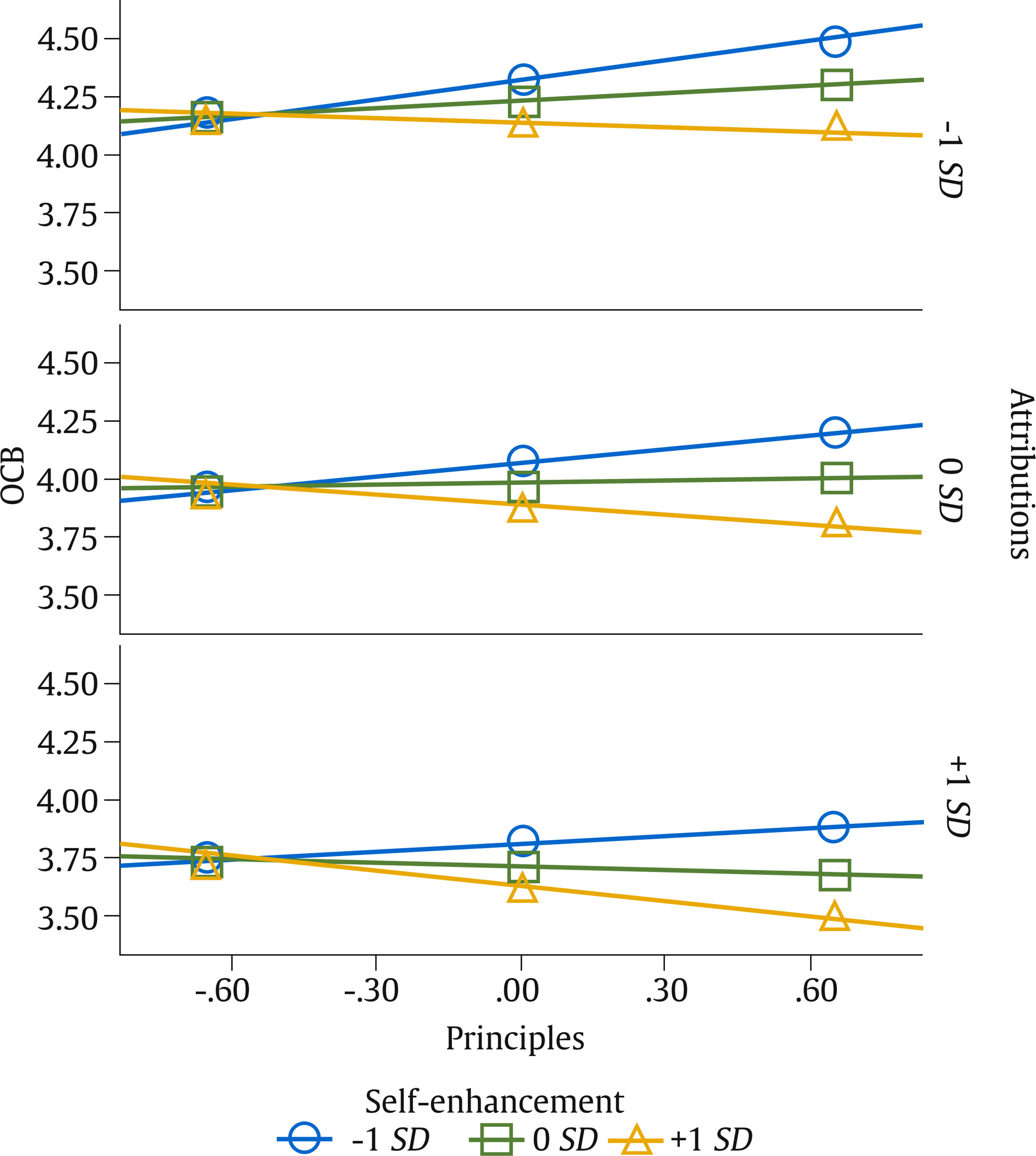

As for the Principle ethical climate dimension, there is a positive effect of this dimension on OCB, β = .80, SE = .28, p = .004, moderated “only” by self-enhancement, β = -.13, SE = .06, p = .023, and not by attributions, β = -.09, SE = .05, p = .080 (see Table 9). It can be seen that “regardless” of the attributions level, the higher levels of self-enhancement, the positive association between the Principle ethical climate and OCB, diminishes, and even becomes negative when the self-enhancement is high. Table 10 interprets this moderation effect statistically, while Figure 6 portrays the effect graphically.

Note. OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors.

Figure 6. Three-way Interaction Effect (Attributions × Principles × Self-Enhancement) on OCB.

Table 9. Moderation Analysis with Principle Ethical Climate Dimension (Study 2)

Note. DV = dependent variable; OCB = organizational citizenship behaviors; INT = interaction effect; 195% CI with 5,000 resampling via bias-corrected bootstrapping.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 10. Conditional Effects of the Focal Predictor (Principle) on OCB at Values of the Moderators (Attributions and Self-enhancement, respectively) (Study 2)

Note. Analysis was based on 95% CI with 5,000 resampling via bias-corrected bootstrapping; 1LLCI = lower limit of CI; 2ULCI = upper limit of CI; 3Low = -1 SD from the mean; 4Mean = 0 SD from the mean; 5High = +1 SD from the mean.

Finally, as shown in Table 11, there is no direct effect of the Benevolence ethical climate on OCB, β = 0.44, SE = .24, p = .068, and it is moderated neither by attributions β = -0.03, SE = .05, p = .597, nor by self-enhancement β = -0.03, SE = .04, p = .494.

Discussion

In the present work, we investigated the implications of employees’ attributions of their supervisors’ decisions on citizenship behavior in the workplace. In particular, following the tenets of the attribution-affect-action model (Weiner, 1980, 2006), we explored whether negative internal attributions of supervisors’ decisions may undermine their OCB, via effects on adverse emotions. In addition, following past research findings on the relationships between organizational- and individual-level factors and OCB (e.g., Chernyak-Hai & Tziner, 2012; Liu et al., 2019; Neale, 2019) – and specifically OEC (Pagliaro et al., 2018; Zehir et al., 2014) and self-enhancement (Arthaud-Day et al., 2012; Bolino et al., 2006) – we examined the way perceived OEC moderates attributions’ effects on OCB and the contingent implication of OEC on OCB while considering levels of negative attributions and self-enhancement.

In support of hypothesis H1, both studies showed that high levels of negative attributions of supervisors’ decisions predict lesser engagement in OCB, and that this effect is mediated by experiences of negative workplace emotions (Study 1). Further, Study 1 supported hypothesis H2, indicating that the indirect effect of attributions on OCB via emotions is moderated by OEC. Specifically, the findings show that disapproving attributions reduce OCB through negative emotions to a lesser extent if there is an increase in perception of organizational adherence to egoism and principle ethical dimensions. Therefore, as predicted, egoism and principle OEC seem to mitigate the effect of negative attributions on OCB. More specifically, employees holding high perceptions of their organization as oriented towards maximization of profit, efficiency, rules, laws, and moral codes are less negatively affected by attributions of their direct supervisors’ actions on their emotions and decision to engage in OCB. Possibly, the employees attribute the negative behavior of their managers to the organizational context, i.e., the atmosphere in which they (the managers) operate, namely, a prevailing organizational climate of egoism and principle.

However, the present findings also show that there is no corresponding effect in the case of the benevolence OEC dimension. Thus, employees’ perceptions of the organization as oriented towards others’ well-being, social responsibility, and friendship do not alleviate attributions’ aversive effects. Although unexpected, this finding resonates with the notion that negative arousal has a significant impact on thoughts and actions, as it constitutes an evolved adaptation that helped our ancestors’ survival in threatening situations (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2000). Past research has further suggested that negative emotions determine individual thought-action repertoires, whereas positive emotions broaden them (see Fredrickson, 2001). Accordingly, it is possible that the positive charge of benevolence-based OEC is unlikely to override the negative effects of unfavorable attributions.

The two studies also supported the hypothesis on attributions’ moderation effect on the relationship between OEC and OCB (H3), indicating that the effect of OEC on OCB is attenuated under high levels of negative attributions. First, there are significant positive effects of the egoism and principle OEC dimensions on OCB, indicating that these dimensions contribute to OCB. This finding may imply that OCB is perceived as a way to promote personal interests at the workplace. Second, OEC’s effects on OCB are moderated by the level of negative attributions of managerial decisions, so that the positive associations between egoism and principle ethical climate and OCB diminish under higher levels of negative attributions. Notably, here, again, the benevolence OEC dimension does not have the same moderating effect.

Finally, supporting hypothesis H4, Study 2 showed that the effect of principle-based OEC on OCB is attenuated given high levels of self-enhancement, while, as predicted, self-enhancement does not moderate benevolence- and egoism-based OEC effects on OCB. These findings support our rationale that since personal and organizational values may not be congruent (e.g., Ostroff et al., 2005; Posner, 2010; Schuh et al., 2018), individual adherence to self-enhancement may come at odds with the moral orientation towards organizational laws and codes in a way that diminishes the manifestation of acquiescence to organizational norms. Accordingly, we find that high-level self-enhancement mitigates the effects of the OEC principle dimension.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The present findings have several theoretical and practical implications. The question of how employees are encouraged to engage in OCB is of great interest to organizational scholars. Yet, while there is considerable literature examining personality factors, workplace context, and LMX, less is known about the way employees’ attributions of workplace issues impact their behavior (Harvey et al., 2014). Notably, while previous research indicated the influence of employee-manager relationships on OCB (e.g., Anand et al., 2018; De Ruiter et al., 2016; Tang & Naumann, 2015), we suggest a more nuanced insight into employees’ inferences regarding their supervisors’ decisions in predicting OCB. The current research addresses this notion by implementing the conceptualization of an attribution-affect-action link, by showing that higher levels of unfavorable internal attributions are associated with higher levels of negative workplace emotions, and that higher levels of negative emotions predict lesser OCB. These findings resonate with the notion of employees’ adherence to the norm of (negative) reciprocity when holding unfavourable perceptions of their leaders (Zhang et al., 2019). Social exchange variables, such as trust, organizational commitment, perceived organizational support, and LMX, were found to be important to relationships between justice, task performance, and citizenship behavior (see Chernyak-Hai & Tziner, 2014). The present findings add to this line of research by showing reduced citizenship behaviors among employees holding negative attributions of their leaders’ functioning and subsequent adverse emotions. Such relationships may imply that employees choose to reciprocate the perceived supervisors’ maltreatment by diminishing OCB.

Additionally, we uncover the way perceived organizational climate, particularly the OEC dimensions, moderate the obtained indirect relationship. Importantly, our findings follow past research arguments that OCB motives may be influenced by various considerations other than mere pro-social motivation. We show that egoism and principle ethical climate dimensions moderate attributions’ effects on emotions and OCB. These findings imply that when employees perceive their workplace’s moral guidelines as emphasizing organizational interest, efficacy and rules, these orientations have important effects on their behavioral decisions so that they reduce (at least partially) the negative impact of unfavorable attributions of their direct supervisors’ functioning. On the other hand (as discussed above), organizational moral guidelines reflective of social responsibility and caring for others (i.e., benevolence ethical climate dimension) do not attenuate attributions’ aversive effects.

Additionally, contributing to the literature on the relevance of individual traits and motivations to citizenship behavior (e.g., Dixit & Singh, 2019; Yildiz, 2019) – and specifically to research indicating the “dark side” of OCB’s motives that are indicative of self-representation tactics (e.g., Arthaud-Day et al., 2012; Bolino et al., 2013; Neale, 2019) – we demonstrate that personal levels of self-enhancement moderate the effect of ethical climate on OCB. Particularly, self-enhancement contributes to the principle-based OEC-OCB link, so that this relationship diminishes in its strength, given high levels of self-enhancement. This finding indicates that when deciding on OCB, employees characterized by high self-enhancement concerns are affected less by adherence to the workplace’s moral orientation towards clear-cut rules and codes; rather, they tend to consider more the merits they will attain following positive citizenship behavior. In other words, when OEC represents compliance with organizational law and codes, this organizational demand may contradict self-enhancement aspirations in a way that attenuates OEC implications on OCB.

As noted, there is no corresponding effect of self-enhancement on egoism- and benevolence-based OEC-OCB links. This latter finding parallels similar observations regarding the motivational foci of self-enhancement and egoism dimensions (Victor & Cullen, 1988), and supports past research conclusions demonstrating that both self-enhancement and generativity concerns promote pro-social behavior (e.g., Urien & Kilbourne, 2011).

The present findings have several practical implications. First, managers should be aware of the ways their subordinates attribute their decisions and actions. To this end, it would be important to encourage open and respectful employee-manager modes of communication. Modern workplaces render these kinds of manager-employee relationships particularly significant because they can take different forms; for example, substantially reduced levels of supervision and diminished face-to-face interactions that are partly due to the current increase in freelancing, outsourcing, and virtual employment (Chernyak-Hai & Rabenu, 2018).

In addition, contemporary managers frequently must cope with employees that represent cultural diversity and various generations characterized by concomitant disparate perceptions and expectations. For example, in contrast to Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) and Gen X (generation X, born between 1965 and 1976), Gen Y employees (born after 1980, also called Millennials; Ramli & Soelton, 2019) expect closer relationships and open communication with supervisors, higher autonomy, and constant rewards and recognition (Chernyak-Hai & Rabenu, 2018). These contemporary working arrangements require sensitive ways of communication and adjustments and would appear to be particularly relevant to the formation of impressions and attributions of decisions and actions taken by management.

Moreover, future studies should explore the “flip side of the coin”, i.e., the way managers’ attributions of their subordinate’s actions affect their (the managers’) emotional and behavioral responses. More specifically, such investigations might also shed light on the effect of management style (transactional versus transformational) on both managers’ and their subordinates’ attributional patterns.

Further, organizations should take proactive measures to pre-empt and alter unfavorable attributions of managerial decisions. Management would do well to bear in mind that attributions impact emotions and subsequent behaviors. We reiterate the need to understand that employees’ propensity to citizenship behavior may be unfortunately disinhibited due to negative emotional states related to the ways they infer their direct supervisors’ decisions. This objective can be achieved by maintaining higher transparency in workplace decisions, so that employees will not necessarily derive that their supervisors’ personal traits or attitudes are accountable for workplace procedures.

Last but not least, the management of organizations should be aware of the ways ethical climate and personality characteristics may alter the implications of employees’ attributions on OCB. We opened the present paper with the question as to whether organizations nowadays can maintain OCB. The present findings may imply that the answer to this question depends on organizations’ ability to create an ethical climate that could diminish potential pervasive implications of employee-manager attributions. In this sense, our results provide additional contribution to the literature exploring interactions between personal- and organizational-level variables in predicting OCB. Specifically, we demonstrated that OEC that emphasizes organizational interests, efficacy, and rules mitigates negative effects of attributions. However, employees’ personality plays an additional role, so that OEC effects may depend on the level of individual self-enhancement. Therefore, organizational human resources units should be aware of, and factor in, employees’ characteristics that have potential implications on OEC-OCB relationships.

Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

Our findings indicate that the relationships between attributions of managerial decisions and OCB are mediated by emotions. Furthermore, the current investigation highlights the moderating role of perceived OEC and self-enhancement in these relationships. Notably, however, there are also several limitations to the present studies that present opportunities for future research.

First, the OEC measure employed in the present study (Cullen & Victor, 1993) includes items of three OEC dimensions (namely, egoism, principle, and benevolence) that are reflective of three levels of assessment within each of them: individual, local, and cosmopolitan. The reliability scores of the OEC measure in Study 2 were sufficient, and therefore no exclusion was made. However, in Study 1, several items were removed from the analyses to ensure sufficient reliability: a single item was removed from individual-level principle OEC, and few items were removed from egoism OEC – one item from the cosmopolitan-level and four items from the individual-level. The four items removed from individual-level egoism OEC are those comprising of “self-interest” (e.g., “There is no room for one’s own personal morals or ethics in this company”). Accordingly, the analyses performed in Study 1 did not include this specific “self-interest” aspect. Although the results of Study 2 replicated the relationships found in Study 1, future research should test the model examined in Study 1 after obtaining reasonable reliabilities among the items, including those pertaining to “self-interest”.

In addition, we should note that while the reliability score of the internal attributions’ measure in Study 1 was not high (α = .56), the corresponding reliability in Study 2 was significantly higher (α =.79). As mentioned earlier, we expected that the correlations between inferred internal causes might not be high due to differences in controllability (e.g., capability versus motivation). Accordingly, the obtained reliability scores could be theoretically justified. However, future studies should consider using different formulations of attribution items to control for inferred controllability.

Another point relates to self-reported measures. Although carefully collected self-reported data can be both valid and significant in providing subjective assessment of organizational behavior (Singh et al., 2016), a limitation of subjective measures may possibly include common-method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To address this potential limitation, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The results indicated that common-method bias is an unlikely explanation of the findings in the two studies. However, future research might employ alternate methodologies, where along with self-reported attributions, emotions and personality inclinations, the variables of OEC and OCB are also assessed by utilizing alternative measures. We should stress that, from the perspective of this paper, where proposed models explore employees’ personal perceptions’ and characteristics’ effects on OCB, perceived OEC may be a more relevant assessment for examining the proposed moderation. Yet, we should acknowledge that employees’ OCB may well obtain further assessment by asking coworkers and managers to rate employees’ citizenship behaviors.

Finally, although the findings of the two studies supported the predicted relationships, it is germane to recall that the correlative nature of the present studies does not generate causal inferences. Moreover, because we investigated attributions’ ongoing implications on emotions and OCB, the present research design was cross-sectional. Future research should establish the causal relationships between the variables. One way to investigate causal relationships could be manipulation (i.e., intervention) carried out to affect employees’ inferences of their supervisors’ behavior in order to affect the way they attribute their actions, followed by measurement of emotions and then tracking their OCB during a specific time frame. The perceived OEC and self-enhancement could be assessed prior to the manipulation.

In addition, future research should explore other organizational level variables, as well as additional personal characteristics in moderating the relationships between employees’ attributions and OCB. For example, one might investigate whether perceived organizational culture and frequency of LMX (i.e., organizational level variables) alter the impact of negative attributions. Research could also explore the contribution of individual traits reflective of internal versus external locus of control and emotional stability (i.e., personal characteristics) on OCB. Finally, past research has indicated that tenure has a positive influence on OCB (e.g., Chou & Pearson, 2011; Delle & Kumassey, 2013; Singh & Singh, 2010). Future studies may explore whether tenure could be another variable that moderates implications of employees’ negative attributions on OCB.

Conclusion

The present research has theoretical and practical relevance for the implications of employees’ attributions on workplace citizenship behavior. Building on the attribution-affect-action model, we demonstrated the way employees’ attributions of their leaders’ decisions associate with their emotions and OCB. Moreover, we indicated that both organizational-level and individual-level variables moderate these relationships, so that the pervasive effects of negative attributions on OCB can be attenuated.