INTRODUCTION

Assessing the effectiveness of the talent development programs is a deeply complex task because there is a diversified group of factors that can contribute to accomplishing excellence in sport (Baker, Côté, & Abernethy, 2003; Henriksen, Stambulova, & Roessler, 2010; Philips, Davids, Renshaw, & Portus, 2010). These factors are identified (e.g. psychological, anthropometric, physical fitness, the coach's role, the significant others); however, their level of importance in each phase of the athletes' careers is still very difficult to understand.

Furthermore, the conception of effective, short and long-term talent development programs is deeply hampered by national and international political, social and economic context. These findings have led to the growth of qualitative studies that aim to find the variables that at each step contribute to the development of the athletes who have achieved excellence in their sports (Raga, Jiménez, Molina, Leite, & Lorenzo, 2012).

From the classic study developed by Bloom (1985) in different areas, there is evidence that talented individuals do not reach an exceptional level of performance for themselves. The role and tasks performed by the coaches and the parents seem to be critical, and their importance differs in each stage of their career. These findings were subsequently corroborated by several studies that reported that the most important components in the development of the sports career of an elite athlete are the learning context (the type of opportunities and the possibility to acquire a quality instruction) and the social relationships (parents, coaches and peers) to which he is exposed (e.g. Allen & Hodge, 2006; Barreiros & Abreu, 2017; Barreiros, Côté, & Fonseca, 2013a; Coutinho, Mesquita, & Fonseca, 2018; Gurland & Grolnick, 2005; Marholz, 2017; Martínez-Moreno, 2017; Matos, Cruz, & Almeida, 2017; Ullrich-French & Smith, 2006). Thus, in the studies reviewed, the coach plays a decisive role in every athlete's development stages (Abbott & Collins, 2004; Elferink-Gemser, Visscher, Lemmink, & Mulder, 2004; Keegan, Harwood, Spray, & Lavalle, 2014; Morris, 2000; Reilly, Williams, Nevill, & Franks, 2000; Williams & Hodges, 2005; Williams & Reilly, 2000). It varies, however, how the elite athletes of different sports characterize their ideal coach, and/or the one that marked their sports career. In this regard, one of the most respected studies in this field, Gould et al. (2002), investigated the psychological characteristics and the development of Olympic athletes through interviews with 10 American medallists, and their significant others (e.g. coaches, parents, tutors). The authors concluded that several individuals and institutions influence the psychological development of athletes including themselves, persons not linked to sports and people connected to the sport and the sport process. In particular, the coach and the family were identified as key factors in its development. This influence proceeded directly through teaching and indirectly by involving unplanned and unintentional situations that contributed to the development of different psychological characteristics. Specifically, athletes state that the most significant coaches in their careers were competent, devoted part of their time to planning individualized training programs, and provided individual attention and support (Gould et al., 2008). Furthermore, these coaches motivated them through emphasizing their expectations and behaviour patterns by promoting discipline, hard work, the attitude that training pays off, and that balance rigour with encouragement and unconditional support to the athlete (Keegan, et al., 2014; Salmela & Moraes, 2003).

With regard to research in this field and considering the aforementioned studies, it seems interesting to understand the distinction of the importance that the club and national team coaches have in the sports careers of a team sport athlete. Will there be differences in the perception of athletes about the importance and characteristics of these two types of coaches whose intervention is highly decisive in the sports career of an elite athlete?

Conjointly, the studies focus on the analysis of the coach who marked the career of the athletes, comparing those who have achieved success with athletes who have achieved less success, not taking into account the difference between the type of coach or the team's performance level or group where they are integrated (e.g. Baker, Côté, & Deakin, 2006; Barreiros, Côté, & Fonseca, 2013b; Ford & Williams, 2012). Thus, and in addition to the type of coaches, it seems important to consider research based on the characteristics of the sport discipline, once it seems possible that in team sports, athletes adopt strategies to succeed not only individually but also according to their teammates' performance (Christensen, Laursen, & Sorensen, 2011; Prieto, Gómez, & Sampaio, 2015). The cohesion, team spirit, and the principle that achieving a common goal has priority over the individual ambitions, are aspects highly engrained in young people in team sports and can influence how the factors that impact athletic performance interact in the different phases of their sports career. In this regard, Macnamara, Button, and Collins (2010) recently interviewed 24 elite-level athletes in team and individual sports and music, about their experience on their way to excellence in their fields. The authors concluded, for example, that a judo athlete relies on the sports structure to track his progress as he advances through the different belts levels. This outcome diverged with his other sport at the time, rugby, whose results were greatly influenced by the team's performance.

In summary, it seems relevant to compare the sports career of elite athletes with different levels of success in the elite years (Bloom, 1985), trying to see if there were common factors that led to the fact that some athletes reached levels of excellence and others didn't. Based on this question, our purpose is to understand the perception of athletes belonging to groups of higher and lower success, about: i) the characteristics of the club and national teams; and ii) if these characteristics are similar in the different stages of their sports development.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

Fourteen elite handball athletes participated in the study, eight women and six men belonging to a group of greater success (men=4; women=4) and a to group of lower success (men=2; women=4). Given the purposes of this study, in the most successful group (groups with a high percentage of athletes called to participate in youth national teams and again to the national team) were considered the athletes with more international appearances in the national team. In the groups' of lower success (groups with a low percentage of athletes called to participate in the youth national teams and again to the national team) athletes with more international presence in the youth national teams and less than five international attendances in the senior team until the 2010/2011 season were considered. The national context of these handball players is very different between genders. Looking at it broadly, the men's National Championship is not yet at the level of competition of other countries where this modality is more developed (e.g., Germany, Spain), but there are several professionals and semi-professional teams. And, it presents a good level, reflecting some excellent results for youth men's national teams in recent years (e.g., 2nd and 5th places in European Championships U21, and 9th place in a World Championship U21). Furthermore, the female National Championship is not professional and the competition level is low. However, there has been a few good results on the youth national teams in the last years (e.g., 4th place in World Championship U17).

Instruments

For this study, data were collected through a semi-structured interview and in an open response, developed upon the interview protocol of Gould et al. (2002), that consists of: a) general questions about the athlete's career and about the characteristics of coaches (e.g. the beginning of sport participation, the support received from parents, coaches, friends, etc.); b) the development of these characteristics for each phase of the sports career defined by Bloom (1985): the early years (the first 3-6 years of participation - 12 and under), specialization years (the next 3-4 years - 13-17 years of age) and the elite years (the next 3- 4 years - 18-22 years of age and older) (Gould et al., 2002). In all of the interviews, the confidentiality and anonymity of the data was ensured. Specifically, all of the names of athletes, coaches, clubs and cities have been changed to letters (e.g., X, Y,...). The interviews were recorded with the athletes' formal authorization, which took place in private locations and were made by the same researcher. All of the interviews lasted 40 to 90 minutes.

Procedures

The interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the data collected was subjected to a content analysis that was done in four stages: 1) with the resort to NVivo 10, the collected information was organized and divided according to the stages proposed by Bloom (1985); 2) ideographic analysis was performed according to the literature (Allen & Hodge, 2006; Barreiros et al., 2013b; Gould et al., 2002; Gublin, Oldenziel, Weissensteiner, & Gagné, 2010; Keegan et al., 2014) deductively and inductively, which allowed the construction of an organized system of general subsamples, general dimensions, themes and sub-themes for each phase of the athletes' career; 3) the inter-expert and intra-expert reliability was processed: (i) by analysing the interviews by two investigators separately and (ii) each of the interviewers doubled 4 of the 14 interviews and only considered that the data were valid when the coincidence rate of analyses was 100%; 4) finally, as a criterion for inclusion of a response in a category or theme, the requirement of agreement from the three experts who belong to the panel of researchers of this study has been defined.

Data analysis

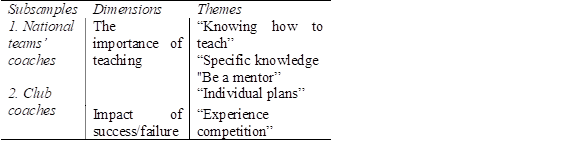

A punctual and multidimensional (Anguera, Blanco-Villaseñor, Hernández-Mendo, & Losada, 2011) deductive-inductive analysis performed in order to meet the objectives of this study. From this procedure emerged two subsamples: a) the national teams' coaches (N.T.C.), and b) the club coaches (C.C). Both subsamples were influence by different dimensions and subsequent themes, according to previous guidelines (Gould et al., 2002), literature analysis and as described in Table 1.

From the units of analysis identified initially in the description of each interview, emerged two dimensions:

1) "The importance of teaching" - It represents the importance of knowing how to transmit the knowledge crucial to the evolution of athlete's different skills. According to Csikszentmihalyi, Rathunde and Whalen (1993), the athletes recognize in their preferred coaches the ability to make them evolve according to their needs. For this dimension, four themes were recognized within the performed analyses: i) "Knowing how to teach": defined as the coach's ability to enhance the athlete's performance in the specific skills of the sport. According to Gould et al. (2002) coaches taught athletes both directly (teaching psychological skills, planned teaching, …) and indirectly (instilling important skills, modeling, …); ii) "Specific knowledge": represents the theoretical and practical skills demonstrated by the coach during the training process (Gould et al., 2002); iii) "Be a mentor": defined as the ability of the coach to understand the athlete's needs, emphasized expectations and standards, hard work, discipline, and the attitude that hard work will pay off (Csikszentmihalyi, et al., 1993; Gould et al., 2002). The literature demonstrates that the behavior of the coach can influence the athlete in several ways, either for the definition of its objectives or for the motivation for the training and competition (Koh & Wang, 2015); iv) "Individual plans": it characterizes the skill of the coach to realize that the athletes are not all the same, that they enter the sports system with different physical and mental skills, technical skills, work ethic, and also psychological disposition (Balaguer, Duda, Atienza, & Mayo, 2002), making it crucial to individualize the training programs.

2) "Impact of success/failure": it represents the relation of the coach-athlete, in the competition, namely how they experience victory/defeat in the competition (Jowett & Cockerill, 2003). For this dimension, one theme was recognized: i) "Experience competition": defined by the coach's experience in training and competition. According to the literature, the way elite athletes characterize their best coaches depends in part on the coach's demonstration of competence during the competition, ultimately express by his/her career experience (Gill, Williams, Dowd, Beaudoin, & Martin, 1996; Hanrahan & Cerin, 2009; Koh & Wang, 2015).

RESULTS

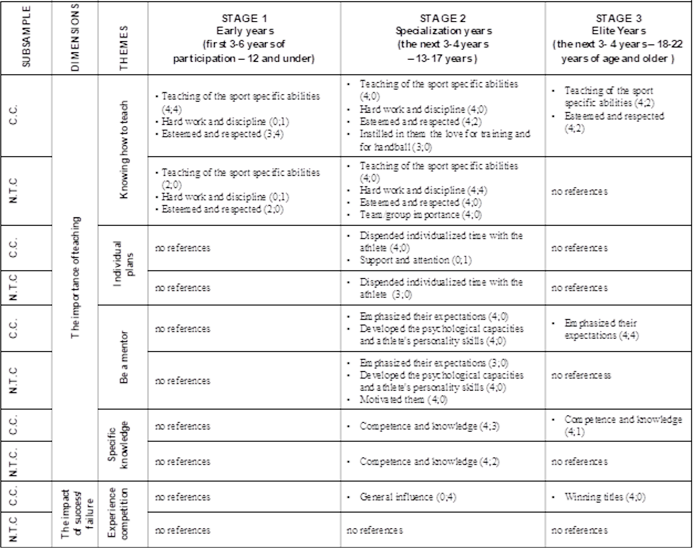

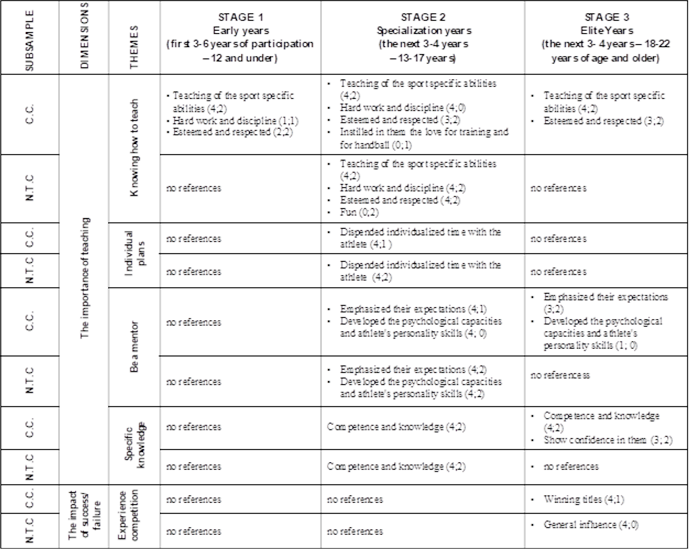

In order to demonstrate the similarities and differences in the perception of athletes from two groups (group of greater success: GS; and the group of lower success: GLS), about the importance that these coaches have had in the development of their sports careers, the subsamples are represented in tables 2 (male) and 3 (female). Each table represents the results for each gender by stage of development (Bloom, 1985).

Several specific themes referred to in the interviewees were organized into two broad dimensions: i) the importance of teaching and, ii) the impact of success/failure. The dimension "importance of teaching" was subdivided into four themes (knowing how to teach, having individual plans, be a mentor and demonstrating specific knowledge). Concerning the second dimension, the results were presented in a single theme about the experiences in the competition. Throughout the text, the themes will be presented in detail and, in most cases, a quote that represents that content will be chosen.

Early years - Stage 1

Several factors were perceived as important in each analysed stage. However, there is a clear perception that both national and club coaches have a higher importance in this stage.

In this stage, some athletes (n=3; Group of success (GS) - male athlete:1; Group of lower success (GLS) - M:1, female athlete:1) explained how their national team coaches emphasized hard work and discipline. The athlete said: "I enjoyed a lot working with coach X. A lot. The coach Y was more smiling. And I liked better the profile of coach X, more rigorous, more serious, to work. (...) I really enjoyed working with her. "(GLS3F).

Similarly, almost all of the athletes (n = 12 - GS-F 3, F: 3; GLS-M: 2, F: 4) reported a great esteem and respect for their coaches in the early years; this was the second most-valued characteristic. An athlete said: "We have created a very strong bond, not just me but the entire team, because he was a master who liked us very much, did a lot for us, was a very humble person also, and we have created a very great empathy. And without him, looking back, many of the initial knowledge (...) were due to many training sessions we did at the time (GS1M).

There was still one athlete of the group of greater success that refers to one coach selection that emphasized her expectations. The athlete said: "I had a Coach (in the national team) that marked me a lot (...). She must have seen something in me that I did not know existed. She spoke to my parents, and she said to them, "she can really go further, if you let her come to the city X to study and for the club Y (...), it could become a serious case "(GS4F).

As can be seen in Table 2, all athletes reported that their club coaches emphasized the teaching of the sport specific abilities; this is the most highlighted characteristic by the interviewees at this stage. Two athletes of the most successful group also highlighted this characteristic about one national team coach. One athlete says: "(...) they began to do individual work with me. While the team was training all together, they put me apart, and I always thought I was grounded, (...) but now realize that they wanted the best for me.

Table 2. Outlook of elite handball male players on the importance of club coach (C.C.) and national team coaches (N.T.C.) to their sports career (Group of greater success, Group of lower success).

Specialization years - stage 2

Regarding the second stage of development of the athlete's sports career, the analysis of the importance of the coach reveals their perception of their national and club coaches. In the male group, there were differences only with regard to the club coaches, particularly in the most successful athletes. In the women's group, we found important differences in the discourse of the athletes of the different group in both subsamples.

Male athletes of both groups and female athletes of the group of greater success (n = 10 - GS-M: 4, F: 4; GLS-M: 2) were unanimous in considering that his national coach emphasized their personality and that their success was determined by that change.

This same factor has been mentioned by the most successful athletes regarding at least one of their club coaches (n=8 - GS-M: 4, F: 4). For example, an athlete said, "I could not have been the player that I became, I would not have come this far, if it wasn't for them (national team and club coach) and I would not have been the person I am today if they hadn't marked my personality at the time " (GS4F).

Also all male athletes and the female athletes of the group of greater success (n = 10-GS-M: 4, F: 4; GLS-M: 2) were unanimous in considering that the national team coach was critical to their teaching process and progress in the sport. For example, an athlete said: "(...) with his tactical knowledge, (...) he made every adversary seem easy. And the level of training sessions changed my opinion on what was done in Portugal. Defense and attack training sessions, he came with new ideas, things that I just was not used to. And he helped me to grow a lot (GLS2M).

This theme was also identified in the speech of the athletes with regard to at least one club coach (n=10 - GS-M:4, F:4; GLS-M:2). Two athletes reported, "At the time (...) he was the senior coach and (I) already worked with him, and also with the coach X, were the two who worked longer with me. At the time they were the two who marked me more, and those who helped me to further develop my skills." (GS3M). Still another athlete said regarding this issue: "(...) I felt a lot of support by the coach at the time (X) that showed interest in teaching me." (GS1M).

Hard work and the demands imposed by the club and national coaches were continuously referenced and although this exigency was the same for all athletes, all athletes, in this case, referred to it including two athletes of the lower success generating (n=12- GS-M: 4, F:4; GLS-M:2, F:2). One athlete said: "(...) our national coach (...) always treated us equally, always made us work hard and it helped us a lot. Hard work helped us succeed." (GS1F). Yet another athlete "For the first time I was called to the national team, (...) the coach X was very hard, really hard, and I loved it. I loved it. (...) I loved that rigor (...)" (GLS2F).

This same factor was also mentioned by the athletes of the most successful group about their club coaches (n=8 - GS-M: 4, F:4). One athlete said: "It was a long time, between ages 16 and 21. These are years that mark us a lot. I was lazy and both the coach of the club, as well as the national team coach, were shouting to me a lot. And it worked well. The more they shouted at me, the better I was. In a sport like team handball, the ability to react under pressure is very important" (GS4F).

Coaches (club and national team) guided the athletes and emphasized expectations and behaviour patterns. This reference to the national team coach is made again for all male athletes (GS e GLS) and female athletes (n=10 - GS-M:4, F:4; GLS-M:2). For example, an athlete says: "To him (the coach selection) was also a big reason for wanting to be better and he also showed me that I could be better" (GS3F). For this purpose, an athlete said, "I think it was a very important factor that he was our coach in the youngest national team, it was not only a coach who knew about handball, he was a coach who knew how to guide athletes" (GS4M). Regarding the club coaches, many athletes also made this reference (n=8 - GS-M:4, F:3; GLS-M:1).

According to several interviewed athletes, the coaches dispense individualized time with the athlete (n=10 - GS-M:4, F:4; GLS-M:2). One athlete says: "And he (chooser) often went to clubs and closely followed our work" (GS4F).

Also several athletes refer to this factor with regard to at least one club coach (n=8 - GS-M:4, F:3; GLS-M:1). An athlete commented: "In the second year, I was fortunate to meet that coach who stayed coaching me long after the training. I think my level was lower than the level of the other athletes and through these individual workouts and this. I do not know. how I shall explain. Good will or insight by the coach. In the following years I think I achieved the best level of my group" (GS4M).

Similarly those athletes report that the fact that the national team coach was very competent and capable was critical to their evolution at this stage of their career (n=10 - GS-M:4, F:4; GMS-M:2). In this regard, two athletes state: "(...) was a conjugating of several factors (the success of their group) and the fact that he was our coach, at that point, and all the ability he had (...) (GS4F). This subtopic is also referred to by several athletes about one of their club coaches (n = 8 - GS-F 4, F: 3; GLS-M: 1).

The national team coaches were respected and esteemed by all (n=10 - GS-M:4, F:4; GLS-M:2). An athlete said: "He was a very kind person and super-experienced and had a special charisma, easily he got the respect of all the players and it's not that easy to be respected by a group of 18 and 19 years old kids (...). He taught us many things and was a very good counsellor.

We all enjoyed working with him. (...) Whatever he said we really obey and respected (...) (GS1M). Yet another athlete said: "I think he marked our entire generation as a person, and as a coach mostly not only in its wisdom that is well known, and was known at the time but as a man, as a person, he marked us very much." (GS4M). Also, with regard to the club coaches, several athletes made this reference at least once (n=11 - GS-M:3, F:4; GLS-M:2, F:2).

Female athletes belonging to the group of more success were also unanimous (n = 4) in considering how the national team coach taught the importance of teamwork: "For me (the fact that our generation has succeeded) was the national team coach, no doubt (...). Because he instilled in us. Not the victories, attention! Winning is always good. But it was the work, the group cohesion; no doubt for me was a secret, the collective. I still apply it today. For me it was him, that national team coach marked us all a lot, and that group cohesion, that inner strength." (GS2F). Yet another athlete said, "the coach inspired us to believe that if we do not work, we harm our colleagues; that was very important" (GS1F).

Similarly, the athletes mentioned above (n = 4) explain how the national team coach motivated them. One athlete said: "The coach X has a strong personality that manages to transmit that as well, to athletes. As a coach, we knew that the work we did in the national team did not end there, it was a job that had to continue at the club. And he knew exactly how to convey this to us, how to motivate us." (GS4F).

Several athletes (n=5 - GLS-M: 2, GS-F:3) report that at least one club coach instilled in them the love for training and for handball. Two athletes comment: "more than the efficiency in the games was the love for training that he instilled in me. Often before practice or according to his availability, we went to his house to see German league games. See how the athletes do, and reacted. Instilled in me this much love to improve, improve, improve, and the love to train." (GLS1M). Another athlete said: "(...) Above all they taught me (club and national coach) not to give up and believe that with hard work, sooner or later, I could become who I am today" (GS3F).

On the other hand, there are factors perceived only by the athletes of the groups less successful with regard to club and national team coaches:

Male athletes (n = 2) refer to this factor. One of the athletes said: "Coach X was more playful, more human in the sense of realizing that we were kids, we had many defects and that little by little we were trying to improve" (GLS2M).

All athletes (F: GLS; n=4) mentioned that the coaches they had on the national teams were important. One athlete says: "(...) when I went to the national team, the coaches were tireless" (GLS1F). All athletes mentioned this factor in relation to coaches at the club. Two athletes commented, "I liked all, I learned a lot from all" (GLS3F). "(...) was the coach I had more years. So I think that influenced me, because I always had proximity with him" (GLS4F).

An athlete also said that the support of the club coaches was very important during this phase of her sports career, she said, "relationship; she (Coach X) was a great support, even when I had personal problems and difficult moments she was there. This was not only in handball; even today (...)." (GLS1F).

Elite years - stage 3

Finally in the elite years of their career (Bloom, 1985), athletes perceive their coaches differently compared to the previous phases and, in the case of women, the differences are substantial.

All athletes, both male and female groups of greater success and the male athletes from the group of less success (n=10), indicated the competence of at least one of their coaches as one of the most important characteristics in this stage. Furthermore, they mentioned that the fact that they won national and international titles with these coaches was decisive and very remarkable to their career. An athlete said: (...) I separate the fact of having won championships with him, from what he helped me as an athlete to overcome. Because I look at myself as an athlete before he arrived and look at me as an athlete after he arrived (...) and I think I am now much more competent, much more prepared for everything." (GS4M).

There are still some athletes who reported that the coaches have shown confidence in them and that that was very important at this stage (n=5 - GS-M:3; GLS-M:2). There is even an athlete (GS) which states that the coach was decisive for his psychological development. The athlete said: "(...) that confidence he shows in an athlete. (...) He trusted me, believed that I was able to be decisive and demonstrated strength in him and passed that strength to me. He gave me the psychological strength, the resistance I needed (...)" (GS4M).

Finally, several athletes report that at least one coach emphasized their expectations regarding their skills. An athlete commented: "(...) He was my coach when I got to the national team (...) was my coach when I gave the most competitive jump. I stop to compete as a boy, as a junior and step to compete in an international form; and actually he has had a very big impact" (GS2M).

At this stage, none of the athletes of the most successful groups referred to their national team coaches. They mentioned the calls to the national team as a pride and a goal, referring to the coaches always in a positive way, but did not state that they had marked their sports career in this phase.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed the speech of athletes belonging to groups that have obtained different levels of success regarding to their perception about the characteristics of club and national team coaches that have influenced their sports career. Athletes have identified several factors as important; however, most of these factors vary between the stages. For example, during the initial years, the references were based mainly on teaching and the empathy created with the club coaches, and there were no significant differences in the discourse of athletes of the different groups. On the other hand, in the specialization years, which are characterized as years of specialization, greater dedication and commitment of athletes (Bloom, 1985), coaches occupy a more prominent place.

Effectively, we noticed differences, especially on the speech of the female athletes regarding the relevance of their club and national team coaches. On the other hand, in the elite years the speech focus of the athletes was solely on the club coaches. The fact that athletes belonged to the national team A, failing to achieve relevant results (qualification to the European Championship, World or Olympic Games), can in some measure help explain these results. That is, despite identifying the influence of the national team coaches as very positive, their influence may not have been so remarkable because the teams failed to achieve the objectives that were proposed. Effectively, the studies in this area were mostly used as a sample Olympic medalist, or athletes with presences at World Championships, which contrasts with the athletes investigated in this study, which leads us to say that the conclusions drawn in investigations of this nature should be tested in different contexts and cultures (Van Rossum, 2001). Most athletes state that the moments at which they achieved titles (national and international) in the clubs were the most memorable moments and reported always to the coach who was leading the team in those periods with high recognition and esteem.

In addition to this feature, the demonstration of confidence by the coach was one of the factors that were only reported by the athletes at this stage. However, as in stage one, there isn't a significant difference between groups, in the perceptions of the most important characteristics of the coaches that marked the interviewed athletes. It is also interesting to note that the aspects related to instruction, to the expectations and to the recognition of the competence of the coaches, are again referred to by most athletes, as it had been in the previous two stages. Effectively, the coaches' teach directly (guiding, teaching psychological skills) and indirectly (caring, paying attention, shaping the personality) affected them. There is also an emphasis on expectations, hard work, discipline and attitude that hard work pays off (Gould et al., 2008). In fact, a recent study in Australian elite athletes (673 athletes from 34 sports), Gublin et al. (2010) demonstrated that at least two thirds of the athletes indicated that the training was critical and influential of their talent in all levels of competition and career stages. The results also revealed that, as they advance through the phases of competition, the perception of the athletes on the importance of the coach is higher. In addition, the coach's ability to motivate and encourage are very important characteristics in a specialization stage (junior and early senior competition).

Also another of the conclusions reported, which is also supported by our study, that during the specialization and elite phases of the athletes' sports career, the detailed knowledge about sport seems to be the most important characteristic of their coaches, in addition to a strong insistence on perfection. Also, in relation to the specialization years, our results showed that the most successful groups, male and female, recognized that at least one club coach and at the same time one national team coach definitively marked their sports career.

We observed only two factors reported solely by the female athletes, as a decisive factor in the national team coach: i) promote the importance of teamwork; ii) the reference to the motivation for training. Although in this study these characteristics appear only in the female athletes from the group of greater success for the national team coach, this aspect is widely reported in the literature, i.e. the fact that the coaches have provided encouragement and unconditional support, encouraging their athletes through motivational techniques and challenges (Allen & Hodge, 2006; Keegan, Harwood, Spray, & Lavallee, 2009; Potrac, Jones, & Armour, 2002; Ullrich-French & Smith, 2006; Vazou, Ntoumanis, & Duda, 2005). In all of the other categories, both successful groups reported similar feelings.

Despite these results corroborating the previous findings by other investigations, recently Brustad (2011) revealed that one of the most overlooked aspects in the design of talent development systems involves the role played by coaches in shaping the motivational orientations of young athletes. These coaches clearly determine substantial changes in the career development of athletes and help them to determine the expectations and achievement standards they can accomplish (Gould et al., 2008), depending on which career phase they are in (Bloom, 1985). To make this possible and as mentioned by many of the interviewed athletes and in this case considering that they practice a team sport, the best coaches devote time to planning individualized training programs, providing individual attention and meeting the needs of the individual.

Note that the female athletes of the group of lower success also demonstrated the same perception of the importance of their coaches but only about the national team coach, i.e., the athletes credit the hard work, the exigency and the fact that they were respected and esteemed by all as a remarkable factor in their career. According to several authors, none of this can be achieved if the coach does not fulfil the expectations of the athletes initially; this is the first step to earning their respect. In their study involving 12 Olympic medalists, Jowet and Cockerill (2003) analysed the nature and significance of the context of the relationship between athlete-coach on three interpersonal constructs (proximity, complementarity and co-orientation). The authors revealed that successful athletes emphasize the importance of common feelings of closeness and respect for their coaches as being essential for any high levels achievement in athletic performance. The results of this study indicate that these feelings of closeness that include feelings of trust, respect, guidance, and the sharing of common goals were highlighted by the athletes as highly important contributions to achieving success. Almost all of the athletes interviewed in this study also report these factors during the three stages of their sports career development. In addition to proximity, the leadership of a group is reported to be decisive for the evolution of the athlete. For Abraham, Collins and Martindale (2006), in a study conducted on 16 elite coaches about the decision-making process, with the aim of proposing a new schematic model, this was one of the roles that were evidenced in experienced coaches, i.e. the development of leadership skills in a team work and in a group of players. This was the most referred to aspect by everyone, either with regard to a national team coach or a club coach.

In the study by Gould et al. (2002) all of the interviewees mentioned the importance of a good coach-athlete relationship, particularly during the specialization years and the elite phase of their sport career. This good relationship was characterized as mutual trust, confidence in the abilities of each other, good communication (especially good listening skills), and a sense of cooperation and mutual aid.

Male athletes from the group of a lower success identified these same categories but only for the national team coach. Concerning this aspect, it seems important to remember that these athletes took a path that was similar to that of his colleagues from another group; that is, when young, they obtained a similar success in the national teams. What differed was the fact that they have not been able to transition to the national senior team, at least continuously. It is, therefore, natural that these results regarding the importance of national team coaches in a sports career are identical it seemed to us that the fundamental difference may be on their path in the clubs, where we identify two factors not mentioned by these athletes: i) had not had the success he had if he (the coach) had not lined my personality at that point; ii) he encourage hard work and exigency. It is clear, therefore, that the coach that marked the athletes of the most successful groups was exigent, disciplinarian, fostered hard work and especially changed their personality. Apparently athletes from the other groups had coaches that marked them, who they liked and who they recognized as competent, but on one hand, it didn't coincided have at the same time a club and a national team coach that marked them or it didn't happen at this age (specialization years).

The female athletes from the group of a lower success also report two factors not distinguished by their colleagues from the group of greater success in respect to their national team and club coaches: i) support and attention and ii) general importance of coaches.

In this regard, Holt and Dunn (2004) studied 34 players (20 international Canadians and 14 young British professionals) and six professional coaches of English football, with the aim of identifying and analysing the psychosocial skills among young players in order to present a consistent theory about the factors that influence success in football. The authors found four psychosocial skills that have proved central to the success of young elite athletes: i) the discipline (e.g. the dedication to the sport and the ability to make sacrifices); ii) the commitment (e.g. motivation and planning career goals); iii) the resilience (e.g. the ability to deal with obstacles); and iv) social support (e.g. the ability to use emotional support, informational and real).

One of the interesting findings of this study indicates that the coaches are not cited as a source of emotional support (which was provided by the parents). Similar results are also reported by other studies such as Rosenfeld, Richman, and Hardy (1989) that in a study with school-aged U.S. athletes, it was found that emotional support was provided by friends and parents and the technical information by coaches and team colleagues.

Recently, Wolfenden and Hunt (2005) report similar results in a qualitative study with three young tennis elite players, his parents and two coaches. The authors aimed to investigate the perception of talent development in tennis and identified six categories associated with the influence of adults (emotional support, real support, informational support, sacrifices, pressure and relationship with the coaches). The authors reported that both parents and athletes are required enormous sacrifices that parents seem to ensure the most significant roles in the emotional and real support of the athlete but are also perceived as a source of pressure when involved too much in the competition. Once again the coach's role was focused on his ability to provide technical guidance.

In summary, all athletes from the group of greater success clearly distinguished during their specialization years, a coach at the club and in the national teams as essential for their success. This fact also happened to one athlete from the lower success group.

They refer to the other coaches they had during all initial stages (early years and specialization years) positively and with great esteem but recognize, and are very specific, that their importance does not compare to those who they identify as crucial in the radical change of their expectations and their goals as handball athletes.

PRATICAL APPLICATIONS

From the data obtained in this study, we can draw an interesting practical guidance not only for the education of coaches, but also for the guidance of directors and parents in seeking the most qualified coaches. Namely, those coaches who have the skills and personality characteristics identified by elite athletes as essential to the maximum development of their abilities in the different stages of his career.

According to the National Program of Coaches Education (NPCE) (IDP, 2010), the skills required to guide athletes in the different stages of their sporting career are defined. However, our results may help to clarify some structural axes of the coach's education; for example, we noticed that in the early years, all athletes reported that not only empathy but also knowing how to teach the specific contents of the game in an integrated way were important factors. Therefore, it is suggested as a way to enhance what is already defined by the NPCE, that general education (e.g. sports didactics) be addressed in an integrated manner, i.e., relating from an early stage the general contents with the specific contents of the modality. To make this possible, these modules should be addressed by experienced coaches who have a theoretical knowledge of all course contents.

On the other hand, athletes during their specialization phase reported that the coaches that had marked them were highly competent and had a detailed knowledge of the sport; that is, once again, knowing how to teach is perceived as a key competence. Furthermore they, not only spend time planning individualized instruction, but were also perfectionists and demanded that same perfection in all training tasks.

These results are very interesting in our opinion to the Federations directors and club officials, not only in order to bet on hiring coaches with this profile, or in the education of their coaches, but also in order to create suitable conditions for them to carry out a work of this nature.

Obviously, these results should be analyzed, considering the cultural and social context of the national handball and it seems important that local, regional and national organizations be proactive in the education of managers and coaches so that they enhance the qualities of each athlete according to their individual needs and depending on the career stage they are in.