Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acción Psicológica

versión On-line ISSN 2255-1271versión impresa ISSN 1578-908X

Acción psicol. vol.12 no.1 Madrid ene./jun. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.5944/ap.12.1.14269

Adoption and LGTB families. The attitudes of professionals in a Spanish sample

Adopción y LGTB familias. Actitudes de los profesionales en una muestra española

Milagros Fernández Molina and Elena Alarcón

Universidad de Málaga

This study was conducted under project grant from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (PB96-0700) and with the collaboration of the Servicio de Protección al Menor de la Delegación Provincial de Málaga de la Consejería de Igualdad y Bienestar Social de la Junta de Andalucía (Andalucía, Spain).

ABSTRACT

The subject of adoption and lesbian or gay applicants has frequently been debated in Spain since the 2005 legislative changes. However, there are few published documents that have addressed the opinions of the professionals responsible for supervision of the adoption process. The general aim of this research was to identify the attitudes of the professionals and case leaders, who work or will work within the adoption process, in relation to same sex parents. With this aim, we used the instruments constructed by Frias et al. (2003) and Brodzinsky (2003), and a questionnaire with 42 questions, which was answered by 38 professionals who agreed to participate. More than 80% considered that the process would have a positive outcome, taking into account the fact that gay and lesbian applicants have to meet the same requirements as any other applicants. However, some professionals feel it necessary to evaluate the applicant's degree of acceptance and satisfaction with their sexual orientation; they also recognize their own need for further specialized training.

Key words: attitudes: adoption; gay and lesbian; same sex couples; beliefs; social professionals.

RESUMEN

La adopción por solicitantes LGTB ha sido muy debatida en España desde los cambios legislativos de 2005. Sin embargo, existen pocas publicaciones centradas en la percepción que tienen los profesionales de la psicología y el trabajo social, responsables de los procesos adoptivos. El objetivo de este trabajo fue identificar las creencias de los profesionales implicados en una adopción. Se usó un cuestionario de 42 preguntas, adaptado de los instrumentos elaborados por Frias et al. (2003) y Brodzinsky (2003), que fue contestado de forma anónima por los 38 profesionales que aceptaron participar en el estudio. Más del 80% considera que la adopción por LGTB tendría un resultado positivo y que a los solicitantes gays y a las solicitantes lesbianas se les debe exigir los mismos requisitos de idoneidad que al resto. Sin embargo, algunos técnicos consideran necesario evaluar el grado de aceptación y satisfacción con la orientación sexual que tienen estos solicitantes, a la vez que reconocen que los técnicos responsables de las adopciones necesitarían más formación especializada.

Palabras clave: Actitudes; adopción; LGTB; creencias; profesionales de la intervención psicosocial.

Introduction

In Spain same sex couples have shown increasing interest in adoption, particularly following the passage of Law 13/2005 July 1, which led to the Civil Code governing the right to marry being amended. This change affects adoption because the new law granted gay and lesbian people the same rights as heterosexual married couples, including regarding adoption (Ley 13, 2005, BOE 157). Professional associations and experts defended the right to adoption for same sex couples in the Spanish Parliament (Infocop, 2005). This law aroused various reactions among the Spanish public in favour of and against gay and lesbian people adopting, similar to the situation in many other European countries (Brulard & Dumont, 2007) However, previously to this law these applicants could adopt and it was known that adoptions by LGTB singles were possible.

A study conducted in the United States showed that less than one-fifth of adoption agencies attempt to recruit adoptive parents from gay and lesbian people, despite the fact that 2 million from the LGTB community have considered adoption as a route to parenthood (Ryan & Mallon, 2011). In Spain, during the first year of the new law, 4500 couples were married and there were 50 applications for adoption (Inforgay, 2006). In 2007, a study found that 44% of the general population accepted that gay and lesbian couples should be able to adopt, and 42% were against this (Fundación BBVA, 2007); four years later the percentage of individuals who accepted same sex adoption rose to 56% (Toharia, 2011). The respondents who provided this opinion were young (between 15 and 34 years), had completed higher education, were non-religious and self-identified as being on the left or centre-left of the political spectrum.

The opinions, beliefs and attitudes of social professionals directly involved in the adoption process are of particular interest, not only because of their personal views regarding the issue, but also mainly because most of the decisions taken during the adoption process will be based on their criteria (Brulard & Dumont, 2007; León et al., 2010; Palacios & Amorós, 2006; Palacios, 2009). Thus begins a complex multistage process in which a variety of professionals (psychologists, lawyers and social workers) play a role within a multi-disciplinary team. Thus, the implicit beliefs of the professionals working with these children affect the entire adoption process, since they face the daily challenge of deciding whether a couple is suitable to adopt, and assessing whether an adoption is a success (Barranco, 2011; Gergen, 2006; Hartman, 1979; Palacios & Amorós, 2006; Paul & Arruabarrena, 1996; Ryan & Mallon, 2011; Shadish et al., 1991; Tornello et al., 2011). Therefore, social professionals should regularly review their personal attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women as parents, in the light of scientific studies that show that GLBT people can become good parents (Gonzalez et al., 2004; Ryan & Mallon, 2011; Tasker & Patterson, 2007; Turner et al., 1990). Researchers have analysed the attitudes and opinions of different groups (most university students) on the rights of gay and lesbian people, on LGTB parenting and adoption, including inter-racial same sex adoption, and recognizing the variables associated with these attitudes (Andersen & Hellesund, 2009; Averett et al., 2011; Camilleri & Ryan, 2006; Crawford & Solliday, 1996; Herek, 1988; Lim, 2002; Moskowitz et al., 2010; Rye & Meaney, 2010; Schwartz, 2010; Tasker & Patterson, 2007).

Most studies undertaken of the attitudes of social professionals towards non-traditional types of families focus on many issues concerning the adoptive families and children (Bao, 2005; Brodzinsky et al., 2002; Chan et al., 1998; Gavriel-Fried et al., 2012; Golombock & Tasker, 1996; Gonzalez et al., 2004; Gonzalez & Lopez, 2005; Guttery et al., 2002; Hall, 2010; Kenyon et al., 2003; MacCallum & Golombock, 2004; Moreno, 2005; Rye & Meaney, 2010; Mallon, 2011; Ryan & Mallon, 2011; Spivey, 2006). Therefore there are fewer studies that specifically investigate the attitudes, tasks, policies, decisions and technical procedures followed in the process of adoption and fostering by gay men or lesbian women.

Kenyon et al. (2003) examined policies and practices relating to adoption by gay and lesbian parents in North Carolina. They conducted interviews in 20 of the 100 Social Security Departments. These authors found a lack of clarity in policies and practice at both the federal and state level and inconsistencies in the protection of equal rights, which made it difficult for them to adopt. Brodzinsky et al. (2002) and Brodzinsky (2003) conducted three studies that examined the degree of acceptance by state and private agencies regarding adoption by LGTB people. These studies reached the same conclusion, identifying three key factors that have an influence on whether LGTB people are considered as possible adoptive parents: the affiliation of the agency, the sex, and the characteristics of the children who need be adopted (i.e., special needs children, sibling groups, older children, etc.). Thus, their results suggest that adoptions of children by lesbian and gay individuals are more likely to occur through public agencies and agencies associated with Jewish and traditional Protestant religious beliefs. Female respondents were more likely than male respondents to report positive attitudes toward adoption by lesbian and gay adults. So, their findings confirmed that gay and lesbian individuals are often seen as a viable parenting resource by agencies specializing in the placement of special needs children.

Spivey (2006) investigated the relationship between sex-role beliefs and attitudes toward same-sex couple adoptions within the Feminist and Queer theory. She used a mailed questionnaire to collect data from a sample of adoption workers and social work students. The findings supported the existence of a positive, linear relationship between sex-role beliefs and attitudes. So, their results show that beliefs are a significant predictor of attitudes: less traditional sex-role beliefs were associated with less negative attitudes toward gay or lesbian couples, and their research supports strong correlations between sex-role beliefs and levels of homophobia.

Hall (2010) examined how Northern California adoption agency caseworkers assess prospective adoptive parents who are gay, lesbian or bisexual. She used a questionnaire for 47 caseworkers from seven country agencies. The factors considered most important to adoption caseworkers, when assessing prospective adoptive parents, were not linked to the adoptive parents' sexual orientation. More than 95% of caseworkers stated that these people should be allowed to adopt, but the respondents were strongly divided on the issue of transracial adoption. Significant differences were found in respondents grouped by race. Results showed that respondents identified as white placed a higher value on prospective parents who exhibited an awareness of racism, homophobia, and religious prejudice in society, among other factors, than those respondents who did not identify themselves as white.

Research questions

The overall aim of this study was to identify the attitudes of professionals working in child protection services toward same sex parenting and adoption via the following research questions (RQ):

RQ 1: What are the professionals' opinions on homosexuality?

RQ 2: What are the professionals' opinions on the civil rights of gay men and lesbian women?

RQ 3: What are the professionals' opinions on the influence of same sex parenting on child development?

RQ 4: What are the professionals' opinions of the assessment and acceptance process for same sex applicants.

Method

Participants

The participants were 38 professionals working in various state and government-funded private adoption and foster care services based in Malaga (Andalusia, Spain).

Instruments

We used a survey with 42 questions taken from those of Brodzinsky (2003) and Frias et al. (2003). Both these instruments have the best psychometric properties. The items from the Frias's Scale were 0.876 Alfa-Cronbach. We used the questions from Brodzinsky's survey. Thus, we used a questionnaire aimed at fulfilling all the following conditions: to collect data on the four research questions, and for it to be simple, brief and easy to complete because of the extremely full schedules of the professionals.

The questions were distributed in three sections: 1. The respondent's demographic data; 2. Data on their place of work; and 3. Attitudes, beliefs and procedures concerning adoption by lesbian and gay people. This last section was organized in four areas: (a) general attitudes and ordinary beliefs towards the aetiology and practice of homosexuality (nature vs nurture, unhealthy vs. health behaviour); (b) civil rights and social recognition of lesbian and gay persons; (c) the effects of living with same sex parents on child development; and (d) technical procedures in the selection of same sex applicants for adoption and foster care.

Procedure

Data were collected in collaboration with the Department of Child and Family Welfare of the Andalusian Regional Government and various government-funded private fostering and adoption associations in the province of Malaga. The initial contact with the social professionals working in these associations was made by a phone call to the directors. We explained the characteristics of the study and asked for their co-operation. This was followed by a personal meeting with them. During this meeting, we presented a semi-structured questionnaire used for collecting information and we explained the procedure for returning the completed questionnaires and many ethical issues. To ensure anonymity, the questionnaires were distributed in identical pre-paid envelopes, with the aim that, upon delivery, there was no possible way of identifying the association or the social professionals. The questionnaires were distributed with a separate sheet that explained the procedure for returning the questionnaire, which again guaranteed anonymity. All the associations contacted agreed to participate. In total, 97 questionnaires were posted and delivered. By the time of the closing date of the data collection period, 38 questionnaires had been returned, representing a response rate of 39.2%.

Design

We used a descriptive design with quantitative data collected on a single occasion through the administration of a survey containing a series of questions from questionnaires that were published before (Brodzinsky, 2003; Frias et al., 2003). The descriptive design has often been used in attitudes studies toward LGTB parenting (Brodzinsky, 2003; Camilleri & Ryan, 2006; Crawford & Solliday, 2010; Hall, 2010; Spivey, 2006). The questionnaire follows the recommendations of validity and reliability (Fernández-Ballesteros y Maciá, 1999; Silva, 1989). Qualitative data were also collected because the participants explained some responses. We respected ethical guarantees according to professional standards (Fernández-Ballesteros & Maciá, 1999).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the SPSS 13.0 for Windows software package. We analysed the response rate using frequency and percentages in each question.

Results

The majority of the professionals were psychologists (51.4%) or social workers (40%), and 82.9% worked in a government-funded private organisation and 62.9% were in training. Their mean age was 34 years (SD 6.8) and 74% were women. The majority were single (51.4%) and without children (60%). Almost all the respondents identified themselves as heterosexual (91.4%). In total, 94.3% reported knowing a lesbian or gay person with whom they had a close friendship (31.4%) or some degree of friendship (48.6%). The rest (20%) did not indicate the degree of friendship. 82.9% reported knowing a lesbian or gay couple; of these, 51.4% had a friendly relationship with them. In addition, 57.1% reported that they were religious. Of these, 48.6% reported that religion was of some importance and 31.4% stated it was of little importance; in fact, 65.7% stated that they never attended religious services. In total, 51.4% stated they had political beliefs; of these 42.9% identified themselves as left wing (labour party or similar) and 5.7% as right wing (conservative party or similar).

Research question 1

Nearly all the participants agreed that homosexuality is not inherited (94.3%) or is not a disease (94.3%), 85.7% replied that it is as ordinary, natural or typical as other forms of human sexuality.

Research question 2

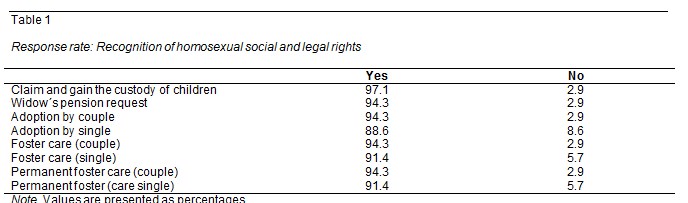

Table 1 shows the percentages of the respondents' replies in relation to the acceptance of civil rights for gay and lesbian people. As shown, 97.1% of the sample supported the right of gays and lesbians to claim and gain custody of their children, and the great majority supported their right to adopt and foster children. Table 1 shows more social professionals supported adoption by couples than by singles. Furthermore, when the respondents were asked whether allowing same sex couples to adopt gave precedence to the rights of the parents over those of the child, 14.3% agreed, whereas 82.9% disagreed.

Research question 3

The respondents were asked for their implicit beliefs about the conditions same sex parents or a family environment should fulfil so that a child is raised and educated properly. Three aspects were considered: the composition of the household, educational difficulties, and the effects on child development.

Regarding family composition, 65.7% replied that "two people were not necessary" for a child to be properly raised and educated, whereas 22.9% replied that a couple was necessary to ensure a child's well-being. Of the former, 51.4% thought the gender or sexual orientation of the caregiver(s) to be irrelevant, whereas 40% thought that gender was relevant. Of these, 48.6% chose a woman as their first choice and 37.1% chose a man as their first choice. The responses of those who chose "a couple" were as follows: 22.9% thought the sexual orientation or gender of the caregivers to be irrelevant, 17.1% chose "father and mother" and 8.6% chose two women.

In relation to the adverse circumstances faced by lesbian mothers and gay fathers when starting a family, the respondents differentiated between couples and singles. Most respondents (94.3%) said that couples would experience difficulties, whereas 74.5% said that singles would. The main difficulties described were given in descending order: rejection by neighbours and those in the immediate environment (20%); rejection by co-workers (11.4%); rejection by the family (8.6%); and sexual behaviour (5.7%). In addition, some respondents (5.7%) thought that singles would encounter more difficulties related to economic resources. The respondents said that same sex parents would have no difficulty in fulfilling the children's physical needs or in educating them. They also stated that the lack of experience, lifestyle and moral behaviour of same sex parents would not lead to problems in relation to educating their sons or daughters.

Most respondents believed that growing up in a same sex family would influence the child's development whether the child was biological (71.4%) or adopted (74.3%). The similar percentages show that professionals believe similarly regarding both ways of belonging to a family, so they do not distinguish between biological and adoptive parenthood. When asked what kind of influence this would have, 48.6% responded that it would be generally positive, 2.9% said it would be generally negative, and 28.6% thought it would be both. Table 2 shows the distribution of responses in relation to positive and negative influences.

Research question 4

This section presents data related to the following aspects: eligibility criteria for gay and lesbian applicants; elements of the assessment process; acceptance of same sex applicants; procedures performed; the characteristics of adopted children; and continuing education requested by the respondents.

In total, 71.4% of respondents thought that same sex applicants should meet the same eligibility criteria as heterosexual applicants, whereas 20% believed that gay and lesbian people should also be required to demonstrate maturity in accepting their sexuality. These respondents gave the following explanations regarding their replies: "You have to assess their self-acceptance and their sexuality, how they handle it, how it affects them, and so on"; (Participant seven); "...the process of building their sexual orientation should be assessed, if it is healthy and if they are accepted within their natural setting." (Participant twenty-two); "...we should assess the process of acceptance of their homosexual identity and the resources available to give children the tools to deal with homophobic behaviour". (Participant thirty-four); "...the level of acceptance of their identity, both personal and in their daily setting." (Participant eighteen); "...explore how they built their homosexual identity, both personally and socially, as well as the strategies and skills they require to work with their children in the face of homophobic reactions." (Participant fifty).

In total, 80% thought that the adoption assessment process should be the same as for heterosexuals, whereas 14.3% thought it should be different. Table 3 shows the aspects which they think should be different. None of the respondents said that homosexuals need more training and preparation, or different preparation, although one respondent thought they needed longer follow-up due to the risk of failure in the adoption process. Some respondents (11.4%) stressed the need to assess whether the applicant's family and those known to the applicant had accepted their sexual orientation, and whether sufficient personal resources were available to the applicants to help their adopted children deal with homophobic behaviour.

In total, 88.6% of the sample would allocate a child to a same sex couple for adoption, which is the same percentage of respondents who would allocate one to a single gay or lesbian. None said they had refused applications on the grounds of the applicant's sexual orientation. One respondent acknowledged asking for information about the applicant's sexual orientation on the application form, seven said they explored it in all applications, as another variable in the psychosocial study, whereas three did so when it appeared that the applicants could be gay or lesbian people. In the case of applicants not declaring their homosexuality during the assessment process, 5.7% of respondents would ignore this fact, 14.3% would include it in the education and training process and explore the motive for concealment, and 8.7% would consult a colleague to make a decision.

Regarding the characteristics of the child adopted or fostered by lesbian or gay single applicants, 17.1% had adopted or fostered healthy babies with no other special characteristics, whereas 74.2% had adopted a child from a 'special group' (i.e., 17.1% adopted children over 6 years of age or adolescents, 14.3% had adopted babies with special needs, 11.4% had adopted children with special needs or children from ethnic minorities, and finally, 3% had adopted sibling groups.

We asked the respondents if they or their agency would be interested in receiving training on working with prospective same sex adoptive or foster parents. The majority (74.3%) were interested in receiving more information about homosexuality compared to 8.6% who thought their knowledge was sufficient to manage requests for adoption or fostering from these applicants. In fact, 60% said they were aware of the scientific studies on same sex families and 54.3% said they were aware of studies on homosexual adoption or fostering. The following content or topics were identified as being of interest to the respondents to receive training: the preparation of children for same sex adoption (60%); the preparation of gay and lesbian adopters (45.7%); attitudes, prejudices and social stereotypes about homosexuality (45.7%); the specific criteria of suitability for gay and lesbian applicants (37.1%); psychological problems of children (31.4%); legal issues of adoption (22.9%); and psychological problems of the adopters (20%).

Discussion

The literature review showed that in Spain no study has been conducted on the opinions, beliefs or level of information of professional teams regarding gay men and lesbian women, and the possibility of them becoming adoptive parents. Few international studies had been done on these issues examining social workers' and psychologists' views. Thus, this is a descriptive study that explores the current situation of the respondents in this field, using a descriptive design. The response rate by the end of data collection was fairly low, but was higher than that obtained by Brodzinsky et al. (2002), although slightly lower than that obtained by Brodzinsky (2003).

Data shows that attitudes toward LGTB people were very positive and these results display a non-pathological view of the etiology of homosexuality, which has improved over time, possibly due to legal changes. The majority of social professionals interviewed understood homosexuality as a way of expressing sexual desire, that is, as natural as heterosexuality. In addition, the respondents considered that gay and lesbian practices cannot be considered a disease, which is consistent with many experts and professional bodies that do not pathologise sexuality (Frías et al., 2003; López, 2004). The raises the question of whether this particular attitude and perspective were due to fact that the majority of respondents were women with a high level of education, and tended to be on the left of the political spectrum. As other authors have suggested, the role of gender in attitudes toward same-sex couples could have a significant moderating effect on homophobia (Crawford & Solliday, 1996; Herek, 1988; Lim, 2002; Moskowitz, Rieger & Roloff, 2010), as well as a set of personal characteristics (being younger, being female, having a higher level of education, not having strong religious beliefs and tending to be politically liberal).

As mentioned, the debate is on-going regarding whether gay and lesbian people should adopt or not, due to the passage of Law 13/2005. According to our data, and consistent with Frías et al. (2003), most social professionals recognize that gay and lesbian people, whether single or couples, are entitled to apply for adoption or foster care. These data are more positive than data shown in the Spanish study by Fundacion BBVA (2007) and four years later in Toharia's study (2011). It showed great advances in the system of child protection, in order to prevent discriminatory and oppressive attitudes (Barranco, 2011; Hartman, 1979; Palacios & Amorós, 2006). However, in addition to recognizing this right, the respondents actually implemented it and included same sex couples and gay or lesbian singles as candidates for children needing adoption. In addition, they considered that these applicants should fulfil the same requirements as heterosexuals and that the adoption process should be the same, as has been the case with single applicants up to the present, who are not questioned regarding their sexual orientation. The only qualification expressed by some of the respondents was that in some exceptional cases they would make further enquiries about the applicant's acceptance of their sexual orientation. They considered that during the eligibility study they would include a psychological assessment of this particular aspect of their personality. This opinion could conceal some discriminatory attitudes because this idea shows a psychopathological view of LGTB.

Regarding the child's wellbeing, the respondents thought that although growing up in a same sex family would have an influence on the child's development, this influence would in general be positive. In total, 3% of the respondents thought that the influence would be negative, because of the potential problems in relation to social integration. This opinion coincides with that of the majority of respondents, who thought that the child may be teased by classmates or have difficulties in making friends. Thus, these problems would not be generated by parents or caregivers, but by peers and, in a general sense, by society. As acknowledged by Cameron & Cameron (2002), Tasker & Patterson (2007) or Tornello et al. (2011), children raised in gay and lesbian families may experience more difficulties during childhood, simply due to growing up in a family that departs somewhat from behaviour socially considered to be "normal", rather than due to the sexual orientation of their fathers or mothers.

In this regard, schools could play a role in assisting the social integration of children living in same sex families, by avoiding or preventing rejection by classmates. In total, 49% of the respondents said that the children may experience teasing from peers. In a study by Frias et al. (2003), 92% of the teachers surveyed said that children with homosexual parents would have problems in social relationships. The difference in the percentages between our study and theirs may be because the respondents in our study do not work in a school context, where there is a greater risk of homophobic behaviour and social rejection, whereas teachers are closer to this situation. In addition, the amount of time that has elapsed between the study conducted by Frias et al. (2003) and our study may explain the current public debate that has stimulated people to think about the issue and form an opinion. This suggests the importance of knowing the views of teachers, as well as the need to equip schools with the materials and training needed to handle sexual diversity, as noted by Moreno (2005). Adjustment to school should be a priority in training programs for applicants and in the monitoring process, to identify risks and prevent problems at school, if required.

Paradoxically, the respondents' opinions on the social rejection of children raised in same sex families are in contrast to the evidence provided in studies. Much research on children raised in LGTB families found no differences in the social development of these children compared to those raised in other types of family (Golombok et al., 2003; Gonzalez et al., 2004; Patterson & Redding; 1996). Thus, it is reasonable to ask whether in fact such difficulties really exist and that the studies have failed to identify them, or whether there is an unfounded expectation on the part of the teachers, social workers and psychologists.

This appears to imply that most social professionals consider that the problem lies not in being educated by one gay or lesbian people or by same sex couples, but whether the social groups in close contact with the new family accept or reject these families. However, social opinion is not the source of paternal or maternal skills; that is, regardless of whether or not society accepts their characteristics, it does not make them incapable of being parents, although it is obvious that the opinions or cultural practices of a specific society at a given historical moment has an influence on parental roles.

Thus, it may be the case that the debate should not focus on whether gay and lesbian people are unfit to be parents; rather the issue should be whether or not society is prepared to accept same sex families, and what should be done to change these attitudes of rejection (Brodzinsky et al., 2002; Gavriel-Fried et al., 2012; Hall, 2010; Mallon, 2011). This would fit in with the changing research landscape, from problematising LGTB families, to a more positive focus on the distinct elements of LGTB parenting. Half the respondents recognized the need for training regarding the negative attitudes, prejudices and stereotypes that they or others may have toward homosexuality, and many also confirmed the need to prepare children and adults in these types of adoption or foster care. Also, interracial and gay adoption both give rise to prejudices, and this is in line with the proposals of Fuentes et al. (2005) or Leon et al. (2010). Thus, it is clear that an essential part of this training should be aimed at helping children and adults to understand and appropriately address certain social attitudes.

Taking into account the foregoing discussion on possible social rejection, and that these are processes involving children "at risk" and "non-typical" applicants, it is striking that no respondent thought that a longer follow-up period was required in the case of homosexual adoption or foster care. One possible explanation is that many of the respondents acknowledged that they mainly worked in training/education, but, paradoxically, they also did not see the need for more, or different, training. The social professionals seemed to focus exclusively on the diagnosis or assessment of "mature sexuality" Possibly their lack of awareness regarding the complexity of this issue led them to consider training or support to be unnecessary. Some respondents indicated that, given an application by a gay or lesbian person, even if the applicant did not declare their status, they would include the issue of gay and lesbian sexuality in the education and training process. This type of response suggests that they do in fact need more support and training, although they do not openly acknowledge this. In fact, 52% saw the need to prepare adults and 44% acknowledged the need for information on eligibility criteria. In contrast, 14.8% acknowledged the need for further assessment and 11% suggested that a different assessment was required. As suggested by the respondents, the only aspects of the process that could differ between gay or lesbian and heterosexual applicants were acceptance of their sexual orientation and provision of the skills to cope with possible social rejection. This suggests that the respondents view LGTB and heterosexual applicants similarly in relation to their ability, skills or resources to be parents, which is very encouraging regarding the future of many children who need families.

In addition, even though this is a minority opinion, it is striking that some of the respondents, when given the choice, preferred a lesbian to a gay man and a lesbian couple to a gay couple, for forming an environment in which children are raised and educated properly. This could indicate they consider that women to be more qualified than men, regardless of their sexual orientation. This would be consistent with the results reported by Flaks et al. (1995). This finding could be also explained by the higher percentage of women than men in our sample.

On the other hand, we found that children who had been placed for adoption or fostering with gay and lesbian families, as acknowledged by some of the respondents, belonged to the 'at risk or special adoption' group. This confirms the results of Brodzinsky et al. (2002) and Brodzinsky (2003) that institutions are more likely to match children in special adoption groups with gay and lesbian applicants. This could be understood as a discriminatory procedure for any professionals.

Finally, the study leads to the conclusion that the real concerns of those who are for or against LGTB adoption or fostering are not focused on their parenting skills, their lifestyle or any negative impact on child development, but rather that the children may suffer social rejection. In addition, the results of this study are very similar to those obtained in studies by Brodzinsky et al. (2002) and Brodzinsky (2003), although the agencies assessed by these authors had more experience in adoption and fostering by gay and lesbian. These children are entitled to be cared for and protected, and society has the duty to guarantee this right under the best conditions possible. Depriving certain types of families, considered suitable by social professionals, of the chance to offer such care and protection to child who needs it would constitute a non-ethical way.

In conclusion, this study has been a beginning in examining professionals' attitudes towards adoption by gay and lesbian parents in a small Spanish sample. It is important to continue with other studies with a larger sample in order to analyse the influence of some variables such us: social factors, individual differences, characteristics of entities, believer differences or participant's sexual orientation. Also, it is necessary to obtain more views on each issue analysed, using a more open qualitative method to provide a better explanation of many responses. We need to know whether what SW professionals stated in thea questionnaire is similar or very different to what they decide during an adoption procedure, due to the potential influence of the Hawthorne effect in the responses in our questionnaire. For future research, also we could analyse the issue of inter-racial adoption and same sex parents. In an international context, the comparison in relation to transracial adoption and interactions between transracial and GLBT adoption is of major importance for policies and practices in child care.

References

1. Andersen, N. & Hellesund, T. (2009). Heteronormative consensus in Norwegian same-sex adoption debate?. Journal of Homosexuality, 56, 102-120. [ Links ]

2. Averett, P., Strong-Blakeney, A., Nalavany, B., & Ryan, S. (2011). Adoptive parents'attitudes towards gay and lesbian adoption. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 7(1-2), 30-48. [ Links ]

3. Bao, A. (2005). Comparecencia de expertos en relación con el Proyecto de Ley por la que se modifica el Código Civil en materia de derecho a contraer matrimonio (Report of experts about Law Project by modification of the rigth to marry in the Civil Code). Diario de sesiones del Senado. Comisión de Justicia, no 189:10-14. Madrid, España: Gobierno de España. [ Links ]

4. Barranco, C. (2011). Buenas prácticas de calidad de trabajo social (Good qualityvpractices and social work). Alternativas, 18, 57-74. [ Links ]

5. Brodzinsky, D. (2003). Adoption by Lesbian and Gays: A national Survey of Adoption Agency Polices, Practices, and Attitudes. Report, Evan Donaldson Adoption Institute. [ Links ]

6. Brodzinsky, D., Patterson, C. J., & Vaziri, M. (2002). Adoption agency perspectives on lesbian and gay prospective parents: A national study. Adoption Quartely, 5, 5-23. [ Links ]

7. Brulard, Y. & Dumont, L. (2007). Synthesis Report. Comparative study relating to the procedures of adoption among the member states of the European Union. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/civiljustice/news/docs/study_adoption_synthesis_report_en.pdf. [ Links ]

8. Cameron, P. & Cameron, K. (2002). Children of homosexual parents report childhood difficulties. Psychological Reports, 90(1), 71-82. [ Links ]

9. Camilleri, P. & Ryan, M. (2006). Social work student's attitudes toward homosexuality and their knowledge and attitudes toward homosexual parenting as an alternative family unit: An Australian study. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 25(3), 288-304. [ Links ]

10. Chan, R. W., Raboy, B., & Patterson, Ch. (1998). Psychosocial adjustment among children conceived via donor insemination by lesbian and heterosexual mothers. Child Development, 69, 443-457. [ Links ]

11. Crawford, I. & Solliday, E. (1996). The attitudes of undergraduate college students towards gay parenting. Journal of Homosexuality, 30(4), 63-77. [ Links ]

12. Fernández-Ballesteros, R. & Maciá Antón, A. (1999). Garantías científicas y éticas de la Evaluación psicológica. In R. Fernández-Ballesteros, Introducción a la evaluación psicológica I (pp.109-134). Madrid, Spain: Pirámide. [ Links ]

13. Flaks, D. K., Ficher, I., Masterpasqua, F., & Joseph, G. (1995). Lesbians Choosing Motherhood: A Comparative Study of Lesbian and Heterosexual Parents and Their Children. Development Psychology, 31(1), 105-114. [ Links ]

14. Frías, M. D., Pascual, J., & Monterde, M. (2003). Familia y diversidad: tipos de padres homosexuales (Family and diversity: types of homosexual parents). IV Congreso Virtual de Psiquiatría. Retrieved from www.interpsiquis.com. [ Links ]

15. Fuentes, M. J., Fernández, M., & Bernedo, I. (2005). Preparación de los niños y niñas para la adopción homoparental (Preparation of the children for gay and lesbian adoption). I Congreso Estatal sobre Identidad de Género y Homosexualidades. Cáceres. [ Links ]

16. Fundación BBVA (2007). Estudio Fundación BBVA sobre Actitudes sociales de los españoles (Fundation BBVA study on spanish people's social attitudes). Retrieved from http://www.fbbva.es. [ Links ]

17. Gavriel-Fried, B., Shilo, G., & Cohen, O. (2012). What is a family? How do social workers define the concept of family?. The British Journal of Social Work, 1(20), 176. [ Links ]

18. Gergen, K. J. (2006). El yo saturado: dilemas de identidad en el mundo contemporáneo (I am satured: problems of identity in contemporary world). Barcelona, Spain: Paidós. [ Links ]

19. Golombok, S. & Tasker, F. (1996). Do Parents Influence the Sexual Orientation of Their Children? Findings from a Longitudinal Study of Lesbian Families. Developmental Psychology, 32, 3-11. [ Links ]

20. González, M. M. & López Gavino, F. (2005). Familias homoparentales y adopción conjunta: entre la realidad y el prejuicio. Matrimonio y adopción por personas del mismo sexo (Homosexual families and adoption: between reality and prejuices). Consejo General del Poder Judicial, 1, 451-473. [ Links ]

21. González, M. M., Morcillo, E., Sánchez, M. A., Chacón, F., & Gómez, A. (2004). Ajuste psicológico e integración social en hijos e hijas de familia homoparentales. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 27(3), 327-343. [ Links ]

22. Guttery, E. G., Friday, G. A., Field, S. S., Riggs, S. C., & Hagan J. F. (2002). Coparent or second-parent adoption by same-sex parents. Pediatrics, 109(6), 1192-1194. [ Links ]

23. Hall, S. (2010). Gauging the gatekeepers: How do adoption workers assess the suitability of gay, lesbian or bisexual prospective parents? Journal of GLTB Family Studies, 6(3), 265-293. [ Links ]

24. Hartman, A. (1979). Finding families. An ecological approach to family assessment in adoption, London: Sage. [ Links ]

25. Herek, G. (1988). Heterosexual's attitudes toward lesbian and gay men: correlates and gender differences. The Journal of Sex Research, 25(4), 451-477. [ Links ]

26. Infocop (2005). Adopción homoparental, un nuevo modelo de familia. Retrieved from http://www.infocop.es/view_article.asp?id=381. [ Links ]

27. Inforgay (2006). Unas 4.500 parejas homosexuales contrajeron matrimonio en el primer año de vigencia de la Ley, según la FELGT (4500 homosexual couples has been married in the first year after law is aproved). Retrieved from www.infoprgay.com. [ Links ]

28. Kenyon, G. L., Chong, K., Enkoff-Sage, M., & Hill, C. (2003). Public Adoption by Gay and Lesbian Parents in North Carolina: Policy and Practice. Families in Society, 84(4), 571-575. [ Links ]

29. León, E., Sánchez-Sandoval, Y., Palacios, J., & Román, M. (2010). Programa de formación para la adopción en Andalucía (program by adoption in Andalousia). Papeles del Psicólogo, 31(2), 202-210. [ Links ]

30. Ley 13/2005, de 1 de julio, por la que se modifica el código civil en materia de derecho a contraer matrimonio (Law 13/2005, july 1, modification of Civil Code about the rigth to marry). Boletín Oficial del Estado, 157. Madrid, Spain: Gobierno de España. [ Links ]

31. Lim, V. (2002). Gender differences and attitudes towards homosexuality. Journal of Homosexuality, 43(1), 85-97. [ Links ]

32. López, F. (2004). ¿Existen dificultades específicas en los hogares con progenitores homosexuales? (Do they have the homosexual homes different problems?). Infancia y Aprendizaje, 27(3), 351-360. [ Links ]

33. MacCallum, F. & Golombok, S. (2004). Children raised in fatherless families from infancy: a follow-up of children of lesbian and single heterosexual mothers at early adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(8), 1407-1419. [ Links ]

34. Mallon, G. (2011). The home study assessment process for gay, lesbian, bisexual andtransgender prospective foster and adoptive families. Journal of GLTB Family Studies, 7(1-2), 9-29. [ Links ]

35. Moreno, O. (2005). Profesorado LGTB: Invisibilidad, falta de formación y escasez de materiales (LGTB teachers: invisibility, and lack of training and resources). In Generelo, J., & Pichardo, J. I. (Eds.), Homofobia en el sistema educativo. Madrid, España: FELGT. [ Links ]

36. Moskowitz, D., Rieger, G., & Roloff, M. (2010). Heterosexual attitudes toward same-sex marriage. Journal of Homosexuality, 57, 325-336. [ Links ]

37. Palacios, J. (2009). La adopción como intervención y la intervención en adopción (Adoption is an intervention and the intervention in the adoption). Papeles del Psicólogo, 30(1), 53-62. [ Links ]

38. Palacios, J. & Amorós, P. (2006). Recent changes in Adoption and Fostering in Spain. British Journal of Social Work, 36(6), 921-935. [ Links ]

39. Paul, de J. & Arruabarrena, M. I. (1996). Manual de protección infantil (Child Welfare Handbook). Barcelona, Spain: Masson. [ Links ]

40. Ryan, S. & Mallon, G. (2011). Introduction. Journal of GLTB Family Studies, 7(1-2), 1-5. [ Links ]

41. Rye, B. J. & Meaney, G. (2010). Self-defense, sexism, and etiological beliefs: predictors of attitudes toward gay and lesbian adoption. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 6(1), 1-24. [ Links ]

42. Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Leviton, L. C. (1991). Foundations of program evaluation. Theories and practice. London: Sage. [ Links ]

43. Schwartz, J. (2010). Investigating differences in public support for gay rights issues. Journal of Homosexuality, 57, 748-759. [ Links ]

44. Spivey, Ch. (2006). Adoption by same-sex couples. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 2(2), 29-56. [ Links ]

45. Tasker, F. and Patterson, Ch. (2007). Research on gay and lesbian parenting. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 3(2-3), 9-34. [ Links ]

46. Toharia, J. J. (Coord.). (2011). Pulso de España 2010. Un informe sociológico (2010 Spain situation. A sociological report). Madrid, Spain: Biblioteca Nueva y Fundación Ortega-Marañón. [ Links ]

47. Tornello, S., Farr, R., & Pattterson, Ch. (2011). Predictors of parenting stress among gay adoptive fathers in the United States. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(4), 591-600. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Milagros Fernández-Molina

Universidad de Málaga

Email: mfernandezm@uma.es

Recibido: 17 de marzo de 2015

Aceptado: 28 de mayo de 2015