Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.12 no.30 Murcia Abr. 2013

ADMINISTRACIÓN-GESTIÓN-CALIDAD

Characterization of the aggressions caused to the medical personnel at the emergency service in a regional hospital

Caracterización de las agresiones producidas al personal sanitario del servicio de urgencias en un hospital comarcal

Ortells Abuyé, Nativitat*; Muñoz Belmonte, Teresa**; Paguina Marcos, Marta*; Morató Lorente, Isabel*

*Nurse. E-mail:

Nortells@ssibe.cat

**Nursing assistant. Servicio de Urgencias Hospital de Palamós. Barcelona.

ABSTRACT

Objective: Workplace violence is an emerging phenomenon in occupational hazards and specifically in the health sector end emergency services. Our objective is to characterize the aggressions caused emergency personnel in a district hospital.

Methods: Cross-sectional study. The study populations are workers in the emergency department. Staff was excluded under one year old. We designed a questionnaire with socio-demographic variables and characteristics of the aggressions in 2011. The response rate was 92.4%. Descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS 16.

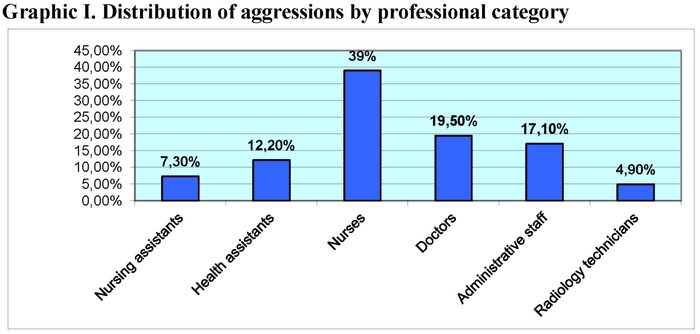

Results: The 58.2% of emergency personnel was attacked: 39% experienced nurses, doctors 19.5%, 17.1% administrative staff, 12.2% auxiliary sanitary, auxiliary nurses 7.3% technical of radiology 4.9%, with a significant association between professional and aggressions (p = 0.004). 40.4% of the aggressions took place in the night 31.9% in the morning and 27.6% in the afternoon.75% were verbal, 25% physical and verbal. 27.5% 4 or more suffered verbal abuse.35.8% of aggressions were committed by attendants, 18.9% of patients and 45.3% for both.71.7% did not report the attack on his high command or the prevention service.67.1% received no training in violence prevention. 69.9% do not know the protocol entity.

Conclusions: Lack of specific training on the issue and dissemination of existing protocols.

Key words: Aggression; emergency service; patients; patient escort service; violence.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: La violencia ocupacional es un fenómeno emergente en los riesgos laborales y específicamente en el sector sanitario y servicios de urgencias. Nuestro objetivo es caracterizar las agresiones producidas al personal de urgencias de un hospital comarcal.

Métodos: Estudio transversal. La población a estudio son los trabajadores del servicio de urgencias. Se excluyó personal con antigüedad inferior a un año. Se diseñó un cuestionario con variables sociodemográficas y características de las agresiones sufridas durante el 2011. La participación fue del 92,4%. Se realizó una estadística descriptiva con el programa SPSS 16.

Resultados: El 58.2% del personal de urgencias fue agredido: enfermería sufrió el 39%, médicos el 19,5%, personal administrativo el 17,1%, auxiliares sanitarios el 12,2%, auxiliares de enfermería el 7,3 % y técnicos de radiología el 4,9%, con una asociación significativa entre categoría profesional y agresiones sufridas (p=0.004). El 40,4% de las agresiones se produjo por la noche, el 31,9% por la mañana y el 27,6% por la tarde. El 75% fueron agresiones verbales, el 25% físicas y verbales. El 27,5% sufrió 4 o más agresiones verbales. El 35,8% de agresiones fueron cometidas por acompañantes, el 18,9% por pacientes y el 45,3% por ambos. El 71,7% no notificó la agresión a su mando superior ni al servicio de prevención. Un 67,1% no recibió formación de prevención de violencia. El 69,9% no conoce el protocolo de la entidad.

Conclusiones: Falta formación específica sobre el tema y difusión de los protocolos ya existentes.

Palabras clave: Agresión; urgencias médicas; pacientes; acompañantes de pacientes; violencia.

Introduction

Violence in general has increased dramatically in the last decades around the world. The workplace violence is an emergent phenomenon in the field of occupational risks and specifically the health sector.

There are multiple definitions of violence at work; Di Martino defined the violence at work as incidents in which the personnel suffer abuses, threats or they are assaulted under circumstances related to their job. Even the way to their workplace, implies an explicit or implicit challenge towards their safety, their well-being or their health(1). Violence is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) (2) as the "intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, development disorders, or deprivation"

In Europe, the International Labour Organization (ILO) states that, from all the employees, the group that suffers the higher percentage of threats at work are the employees of the public administration, and especially those who gather a higher percentage of violent acts are the health workers (24%) (3).

Holland, Italy, France, Sweden and Belgium, due to the importance of the violent matters, have adopted specific plans in order to face this situation (4).

Spain is not different to the rest of Europe, the proliferation of violent acts is not only expressed in specialized press but it is also reflected in other mass media. A 60% out of the 200.000 doctors in Spain have received threats (4).

In 2007 it was taken a step forward in the legal issue. The Constitutional Court passed a sentence in which the aggressions to the public health professionals are described as a crime against a civil servant. The importance of this sentence was that the aggressors face jail, higher compensations and the aggressor will have criminal records (4). Nonetheless, aggressions don't decrease.

The International Council of Nurses (ICN) (5) in its report with international results states that nurses are the health professionals that run the highest risks of suffering workplace violence.

In Catalonia, the Official School of Doctors from Barcelona (COMB into Spanish) (6) carried out a report about workplace violence where it is highlighted that a 45% of the aggressions occurred at emergency services, a 28% in primary attendance and a 13% at the hospital rooms.

The emergency services and the psychiatrists are the ones which more aggressions gather (7,8,9). Although at this moment violent acts can be produced at any health service, even services where there were traditionally only a few, the consequences of these ones can be even worse now as they don't have the structure and the preparation to prevent them.

Circumstances that favour the violence are related to the work organization and the environmental structure. So then, the overcrowding and small rooms, the scarcity of human resources plus the lack of information, stressful situations and the increase of wait time favour the aggressions to the health personnel (7,9). These circumstances are reached in the majority of the emergency services.

In primary attendance, the probability of suffering an aggression is 6, 2 times higher, if the professional is on guard (10).

The literature shows that the consequences of the workplace violence have direct costs (11) such as the absenteeism, and indirect ones such like demotivation and the decrease of the care quality. At a personal level, it can produce stress, anxiety, a lack of the self-stem, emotional distress (12,13) and it can alter personal relationships with the family which is the co-lateral victim.

Violence affects to the victims and affects to the enterprises, that is the reason why the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) (14) urges the hospitals to assume duties in the prevention of the violence and it recommends to clarify to the patients that no type of violence is accepted, to set a program of formation for the employees, to adequate the staff, to increase the vigilance and the security, by making protocols and registers of aggressions (15).

In order to make a good prevention of the violence it is necessary an objective knowledge of our reality, that is the importance of our study which allows us to have a map of the state of the workplace violence in the emergency services.

The main objective of our study is to characterize the aggressions produced to the personnel of the emergency service during the year 2011 and the secondary objective is to obtain a map of the situation regarding knowledge of the personnel about existent protocols, formation and declaration of violent acts.

Methods

Transversal study. A questionnaire with socio-demographic variables, type of contract, years of experience and shifts was designed. The type and number of aggressions suffered during 2011 were counted. Also, the received formation, the knowledge of existent protocols, the consequences of the aggressions, the notification and the feeling of safety at the emergencies service was registered.

The questionnaire was sent to the work e-mail, using the Limesurvey program that keeps the confidentiality of the received data. A testing was done in advance to check the right understanding of the survey and some of the questions were reformulated later in order to increase the validity of the answers. When the survey starts, the definition of what is considered as aggression by the WHO is provided, and it is the same definition that appears in the identity protocol.

The population of study is composed by the active workers of the emergency services at Palamós hospital where nurses, doctors, nursing assistants, health assistants, radiology technicians and administrative personnel were included. Staff who had worked less than one year at the emergency services, those who were in absence, holidays and personnel on guard (resident and specialist) was excluded. A total of 79 questionnaires with a participation of the 92,4% were sent.

Data was inserted in a database and a descriptive statistic was carried out by means of frequencies and Fisher exact test with a level of reliability of 95% with the SPSS 16 program. To carry out the study, the manager, the emergency coordinator and the prevention service gave their approbation.

Results

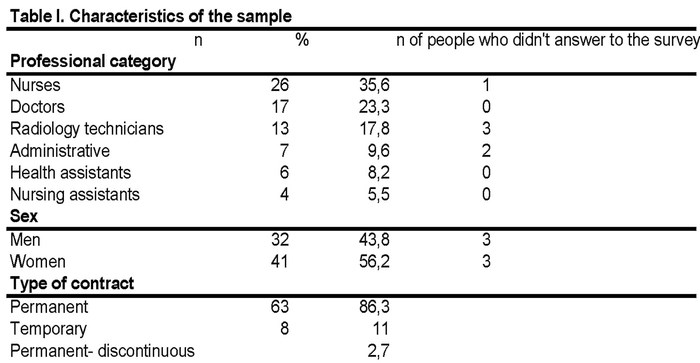

73 people answered in total. The characteristics of the respondents are shown at table I.

The 58,2% of the respondents were attacked during the year 2011. In graphic I it is shown the distribution of the aggressions where it is enhanced that the 39% of the attacked people were nurses with a significant association between the professional category and the suffered aggression (p=0,004)

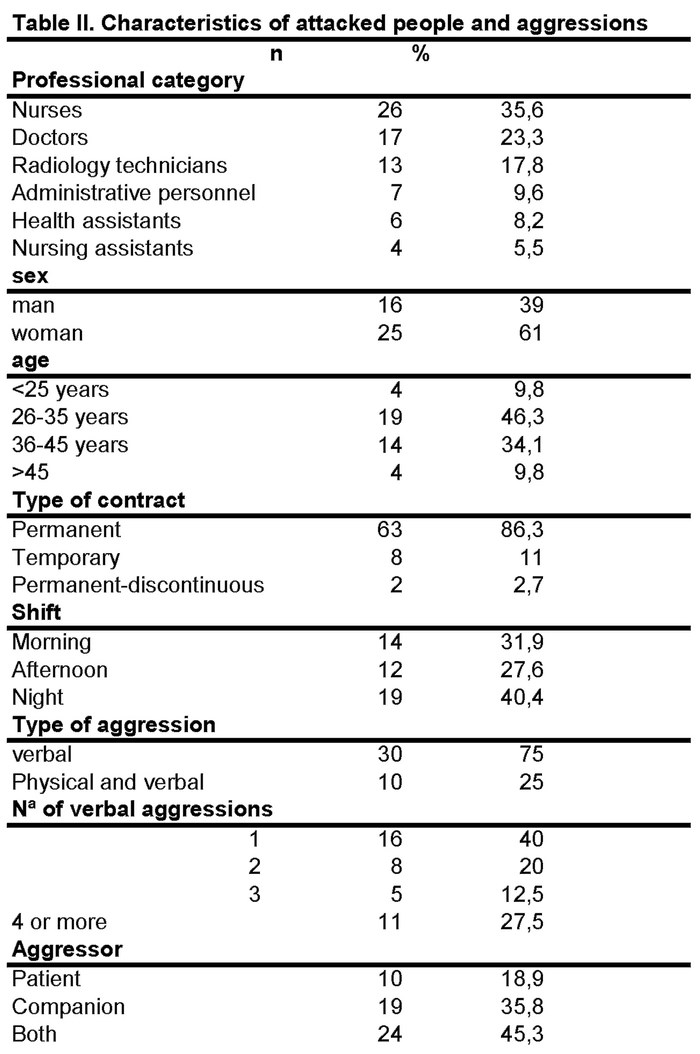

Table II shows the distribution of aggressions regarding age groups with a predominance of the 46, 3% of the professionals among 25 and 35 years old.

Moreover, the 66, 7% under 26 years suffered aggressions whereas older people tan 46 suffered a 44,4%, not being statistically significant.

The characteristics of the attacked people are shown in table II, where it can be seen that the 61% of the aggressions were suffered by women, the 82,9% had a permanent contract, normally at night shift with a 40,4% and the majority of the aggressions were verbal (75%).

The years of professional experience and having suffered or not any aggressions are reflected in table III where it can be state that there is no significant relationship between these two variants.

The 27,5% of the attacked people has suffered 4 or more verbal aggressions (Table II).

The 88,8% of the physically attacked people have suffered an aggression and the 11,2% have suffered two.

The 35,8% of the aggressions were committed by the patient's companion, the 18,9% was done by the patient and the 45,3% by both of them.

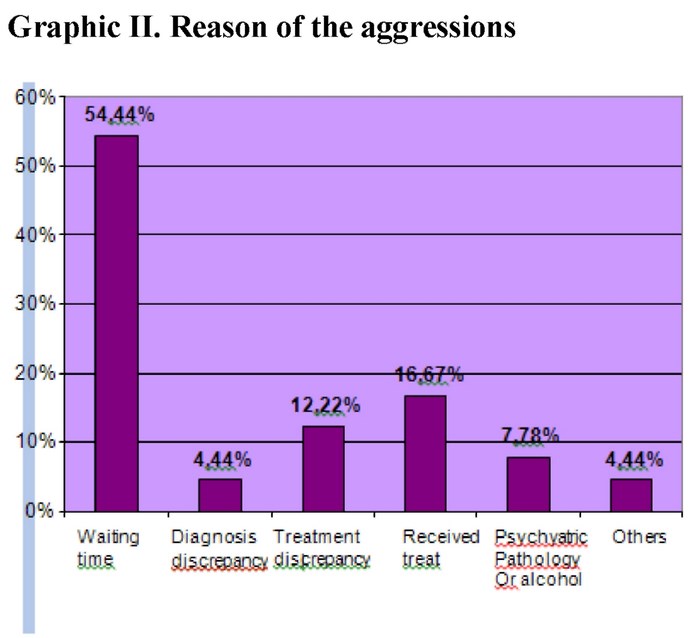

The reasons for these aggressions are observed in the graphic 2, it is significant that the 54,4% is due to the waiting time.

The consequences of the aggressions were the following: 10 people suffered persistent memories of the attack, 5 people demotivation and 3 people severe vigilance.

The 71,7% didn't notified the aggression to the higher manager, note even to the preventive service, the 20,8% notified any aggression and the 7,5% notified all the suffered aggressions. The reason for not declaring them was: the 43,1% considered that the aggression was not so important, the 36,2% didn't know that they had to declare them. The 17,2% considered that they were useless and the 1,72% because they didn't want to see the patient anymore.

The 92,6% didn't denounce the facts to the police, only one person did it. The reason for not denouncing was the following: the 30,8% because they consider that it makes no sense, the 5,8% didn't know that they could denounce and the 3,8% because they were frightened.

The 76% of the respondents consider that the physical space of the emergency service is appropriate or very appropriate for the prevention of violence. The 58,9% consider that the presence of vigilance is little or inappropriate. The 47% consider appropriate the global security in the emergency services.

The 67,1% have not received the formation of prevention of violence. The 69,9% didn't know the protocol about entity violence.

Discussion

More than a half of the emergency personnel have suffered any aggression during the last year. These results aren't encouraging, although other studies (12, 16, and 17) show results even more disturbing, both in the emergency services and the health professionals in general.

Several studies (7,11,18) show that the nursing personnel are the group more punished by violent behaviours, like it is also shown in ours.

In spite of the fact that the percentage of aggressions is higher in nursing, we also highlight that the 100% of the admissions personnel was verbally attacked. Admissions staff is the personnel that first meet the users and it is the one that receive the first demands on the behalf of the patients and/or companions that are in the waiting room.

As the work experience increases the percentage of aggression decreases, although it isn't statistically significant, as it occurs in García-Macía (19) study.

The percentage of aggressions suffered by women is higher than men. This could occur for two main reasons; the first one because there are more women working at health service and the second one is because historically, violence against women is imbricated in the social and cultural rules that perpetuate the inequality between women and men that forgive and favour the discrimination against women, including physical and verbal violence on the half of men and other people. In spite of the fact that there have been an important recognition of the violence towards women and the achieved progress during the last years; it is still a problem of great importance.

In the distribution of aggressions by time shift, there isn't any homogeneity in the bibliography. In our study, the aggressions at night shift predominate, in the one made by Cantera (11), the aggressions at the morning shift predominate (11) whereas in the one made by Villar (7), it is observed an increase of the aggressions at the afternoon shift. The different hospital infrastructures, the distribution of the personnel, and the affluence of patients can justify the difference of aggressions by shifts. In our case, the night shift suffers an important reduction of nurses and doctors. This fact increases the delay in the attendance and taking into account that the waiting time was the factor that triggered the violence; this could be the reason of the predominance of aggressions during the night shift.

The verbal aggressions where we include threats, coercions and insults predominate in all the studies (11-20). We highlight that the 27,5% of the professionals of our service have suffered 4 or more aggressions in one year, although far from the study by Fernandes (13) where a 43% suffers a verbal aggression by shift.

The 25% of our aggressions were physic, contusions and erosions, although none of them required a sick leave different of the study by Villar (7), where a 7,3% of the attacked people needed a sick leave provoking 862 lost working days.

The companions take part in an 81% of the aggressions that were produced.

In our service, it is allowed one companion all the time and in the paediatrics case we allow the entrance of both parents. The companions inform us about what happened, they give company and support in the control of the patients. In the emergencies, in moments of nervousness, lack of information or waiting, the family and /or companions can adopt violent attitudes, participating in the majority of aggressions produced in our service.

Martínez-Jareta (16) in his multi-centre study explains that only a 15% of the aggressions are produced by companions although, the sample consists of workers at hospitals and centres of primary attention, not only emergencies as it is in our study.

The main reason of the aggressions, according to the professionals, is the waiting time (54,4%), followed by the received treat and the disagreement related to the treatment. The psychiatric pathology and/or being under the effects of alcohol or drugs represent a 7,7% in the study of the COMB (school of doctors from Barcelona (6) this type of aggressors represents the 21,5% of the total. In the study by James et al(21) it is reflected that the physical aggressions are more frequent in psychiatric patients or under the effects of alcohol or drugs.

The aggressions are associated to demotivation (10,11,12). The stress associated by the aggressions provokes maladjustment answers such as anxiety, psychic and post-traumatic disorder symptoms (17).

In the study by Cantera (11), the 22% of the attacked suffered psychological repercussions, these data are very similar to ours.

Workplace violence can have a double negative effect. The first one related to the person, decreasing the motivation, implication and work performing, as much as the emotional alterations that can affect to the personal and social relationships. Secondly, regarding the self-organization it increases the absenteeism at work, it decreases the care assistance quality and it damages the relationship among professionals and users (22). In the global evaluation of the security at our workplace in the emergency service, the half of the professionals has approved it

The best valued is the physical space, as a demodulation of the emergency service was carried out in 2010, creating wider rooms, individual closed boxes, separating different waiting rooms and decreasing the pressure of both patients and family. The failure is related to the assessment of the presence of a security vigilant. There is only one professional for the whole hospital as much as for the parking of the building. His presence in the emergency service is practically none except for his requirement by phone.

Studies (13,14) recommend security 24 hours a day and alarm systems, bells to ask for help and in the extremely dangerous areas video-vigilance systems. Hospitals in the United States include metal detectors.

A computer tool of recent implantation in our service is the Brieffings of security. This is a computing alarm which can activate the different professionals of emergencies. This alarm shows that a certain patient must be guarded. The Brieffing can give us information on the half of the doctors (shock risk, cardio-vascular risk...) as a security alert of physical integrity (risk of falling, aggressive patient...). This information can help us to prevent a violent situation informed in advance.

A common fact in the different studies (7,8) and which also happens in ours is that health professionals tend to minimize the aggressions, incorporating them as part of our work and empathizing with the stressful situations of both patients and companions. This fact is a mistake as the human dignity can't be trashed under any circumstances.

The great lack of awareness about workplace violence protocol on the half of the workers at emergency shows that it isn't enough the elaboration of itself. The success is on the spread. It isn't enough to upload it on the intranet, it is necessary to make informative meetings and to spread these protocols. The company should get more involved in training its professionals by offering them specific training of how to face and to solve conflict situations offering tools such as management of the stress strategies and techniques of self-control to avoid and prevent them. This is our slogan: "better safe than cure"

A limitation of the study would be the tendency to minimize the aggressions. This is a fact that would have decreased the cases of violence.

Conclusions

Workers at the emergency service are more vulnerable to suffer aggressions at their workplace although the most attacked of the service are the nurses from 26 to 35 years with a permanent contract and at night shift.

Formation is the main foundation to prevention; it is something to improve in our service.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our acknowledgment to Inma Sánchez, epidemiologist of the Department of Investigation and Research at Palamós Hospital, due to her invaluable help.

References

1. Di Martino V, Hoel H, Cooper CL. Preventing violence and harassment in the workplace. 2003. [ Links ]

2. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Informe mundial sobre la violencia y salud. Genebra (SWZ): OMS; 2002. [ Links ]

3. Chappell D, Di Martino V. Violence at work. 2000. (Consultado en Octubre 2011) Disponible en: http://www.ilo.org/english/protection/safework/violence/violwk/wiolwk.htm. [ Links ]

4. Martínez León M, Queipo Burón D, Martinez León C y Torres Martín H. Aspectos médico-legales de las agresiones al personal sanitario como delito de atentado. Revista Sideme. 2010. Número 5. Julio-Septiembre. [ Links ]

5. Consejo Internacional de Enfermería. Hola informativa: una epidemia mundial. (Consultado Octubre 2011). Disponible en: http://www.icn.ch/images/stories/documents/publications/factsheets/19kFS-violencia-Sp.pdf [ Links ]

6. Collegi Oficial de Metges de Barcelona. Violencia en el lloc de treball. Servei d'informació collegia! Num.110.2004. (Consultado en Octubre 2011). Disponible en: http://www.comb.cat/cat/actualitat/publicacions/sic/sic110/sic06.htm [ Links ]

7. Villar M, Aranaz JM. Violencia en el medio hospitalario por pacientes con enfermedad mental. Arch Prev Riesgos Labor. 2005;9(1):20-27. [ Links ]

8. Paravic Klinj T, Valenzuela Suazo S, Burgos Moreno M. Violencia percibida por trabajadores de atención primaria. Cienc Enferm.2004;X(2):53-65. [ Links ]

9. Carrasco Rodríguez P, Rubio González LM, Vilchez Castellano S, Villalobos Buitrago D. Estudio de las agresiones recibidas por el personal de enfermería y de las vivencias al respecto en los servicios de urgencias de los hospitales de la comunidad de Madrid en un trimestre. Nure investigación, na26, Enero-Febrero 2007. [ Links ]

10. Moreno Jiménez MA. El médico de familia ante la violencia verbal de los pacientes. FMC. 2004;11(5):225-8. [ Links ]

11. Cantera LM, Cervantes G, Blanch JM. Violencia ocupacional: el caso de los profesiolanes sanitarios. Papeles del Psicólogo. 2008;29(1):49-58. [ Links ]

12. Simoes Cezar E, Palucci Marziale MH. Violencia en el trabajo en una unidad de emergencia de hospital de Brasil. 2006 Nov. Nure Investigation (serie en Internet). (Citado el Octubre 2011); Disponible en: http://www.fuden.es/originales_detalle.cfm?ID_ORIGINAL=102&ID_ORIGINAL_INI [ Links ]

13. Rumsey M, Foley E, Harrigan R y Dakin S. National overview of violence in the workplace. (2007). Australia: Royal College of Nursing. [ Links ]

14. Distasio C. Violencia en el lugar de trabajo. Nursing. 2003; 21 (1):14-19. [ Links ]

15. Doody L. Eliminar la violencia en el puesto de trabajo. Enfermería hospitalaria Nursing. 2004; 22(4):30-4. [ Links ]

16. Martinez-Jarreta B, Gascón S , Santed MA, Goicoechea J. Análisis médico-legal de las agresiones a profesionales sanitarios. Aproximación a una realidad silenciosa y sus consecuencias en la salud. Med Clin. 2007;128(8):307-10. [ Links ]

17. Gascon S, Martinez-Jarreta B, López Verdejo MA, López-Torres J, Castellano M. Respuestas desadaptativas al estrés derivadas de agresiones a profesionales satitarios. Revista de la Sociedad Española de Medicina y Seguridad del Trabajo. 2008;3(3):103-105. [ Links ]

18. Gil Hermandez MR, Morales Cobo MC, del Rio Aragó P, Martin Duran AM, Peñalvo Espinosa R. Violencia: una constante en el servicio de urgencias. Ciber Revista 2008. (serie en Internet). (Consultado en Octubre 2011).Disponible en: http://www.enfermeriadeurgencias.com/ciber/septiembre/pagina7.html [ Links ]

19. Garcia-Macià, R. Prevención de la Violencia en el Personal Sanitario. VI Congreso Internacional de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales. La Coruña, mayo de 2008. [ Links ]

20. Madrid Franco J, Salas Moreno MJ, Madrid Franco M. Situación de las agresiones a Enfermería en el Área de Salud de Puertollano. Enfermería del Trabajo 2011;1:11-17. [ Links ]

21. James A, Madeley R, Dove A. Violence and aggression in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:431-434. [ Links ]

22. Miret C, Martínez Larrea A. El profesional en urgencias y emergencias: agresividad y burnout. An Sist Navar. 2010;33:193-201. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em