Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.17 no.49 Murcia ene. 2018 Epub 14-Dic-2020

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.17.1.280741

Originales

Anxiety among caregivers of patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease after hospital discharge

1Departamento de Trabajo Social y Servicios Sociales, Universidad de Murcia. España.

2Servicio de Neumología, Hospital Morales Meseguer, Murcia. España.

3 Instituto Murciano de Investigación Biosanitaria Virgen de la Arrixaca (IMIB). Murcia. España.

4Departamento de Fisioterapia, Universidad de Murcia. España.

5 Departamento de Enfermería, Universidad de Murcia. España.

6 Euses Escola Universitària de la Salut i l´Esport, Universitat de Girona. España,

Objective:

To identify the factors that influence changes in caregivers anxiety status three months after discharge for acute exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

Methodology:

Longitudinal study. Participants included 87 caregivers of patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD. Anxiety was measured at the time of hospitalization and three months after discharge. We measured factors from four domains: context of care, caregiving demands, caregiver resources, and patient characteristics. We used multiple univariate and multivariate logistic regressions to determine changes in anxiety three months later. Univariate and multivariate multiple logistic regressions were used to determine changes in anxiety three months later.

Results:

A total of 57.5% of caregivers reported anxiety at the time of hospitalization. Of these, 44% had a remission of their anxiety three months after discharge. However, 22% of caregivers who had not experienced anxiety at the hospitalization became anxious at 3 months. The severity of COPD and not receiving help from another caregiver decreased the likelihood of remission of anxiety. Moderately high overload increases the likelihood of experiencing anxiety symptoms.

Conclusions:

The perception of anxious symptoms is dynamic. Caregivers are likely to recover from anxiety when they receive help from another caregiver and if the patient they are caring for does not have severe COPD.

Keywords: Anxiety; Caregivers; Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; Family Care; Exacerbations

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic and debilitating health problem characterized by impairment in the ability to perform activities of daily living. 1 Many of these patients need help with health care and management of daily life. In Spain, the majority of people with COPD received the attention of caregivers because of their disability and it is estimated that 88.6% of the main caregivers were relatives of friends, this is informal caregivers.2)

In advanced stages of COPD, exacerbations may occur and whether the patient may require hospitalization.3) In these circumstances, informal caregivers play a very important role.

It is well known that caregivers of COPD patients may experience significant burden,4)(5)(6 in addition to the occurrence of exacerbations and hospitalizations are distressing situations for caregivers,7) which appears to be reduced within several weeks of hospitalization.8) The presence of depressive symptoms in caregivers has been observed to be present during hospitalization, but after discharge from the patient, the level of dependence of the patient will be determinant for the presence of depressive symptoms.9)

On the other hand, caregiver anxiety is a common problem during hospitalization 10, but its evolution may be different later in the patient's home when the caregiver is confronted with very stressful situations such as dyspnea.11 The objectives of this study were to describe the anxiety of the primary caregiver at 3 months after hospital discharge due to acute exacerbation of COPD and identify factors that may have influenced the change in anxiety.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design and participants

Longitudinal study. Caregivers of patients hospitalized for exacerbation of COPD were recruited at Morales Meseguer Hospital, Murcia, Spain, between October 2013 and May 2015.

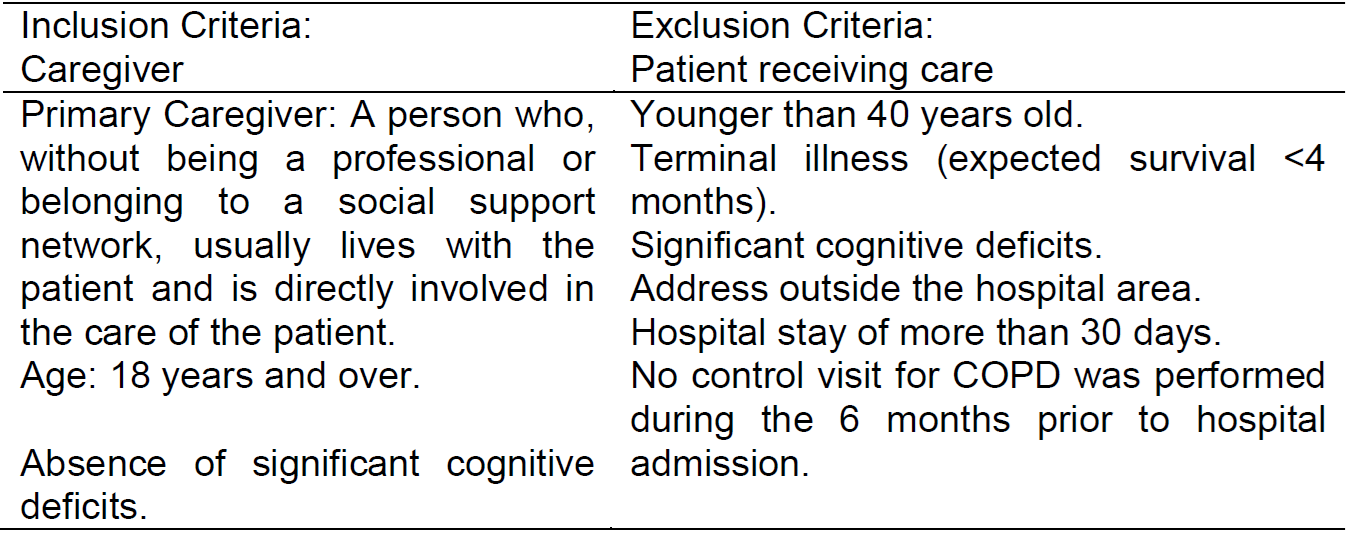

Based on patient health reviews and review of medical records, a pulmonologist identified and recruited a consecutive sample of primary caregivers who met the criteria (Table I). All caregivers and study patients were informed and completed informed consent, and the hospital ethics committee approved the study protocol.

Measurements

Data were collected in face-to-face interviews with caregivers and patients in the hospital and in telephone interviews 3 months after hospital discharge.

To assess caregiver anxiety, we used the anxiety subscale of the Goldberg test to highlight the presence or absence of anxiety symptoms in the caregiver.12)(13 This scale includes nine items that ask respondents to rate the presence of symptoms using binary response categories (yes / no). The score ranged from 0 to 9, and a cutoff of 4 is used to discriminate caregiver with anxious symptoms ((4, yes) from those without symptoms (<4, no).13) This instrument was administered at the hospital at admission and at home 12 weeks after hospital discharge.

Potential associated factors were classified into four domains: context of care, caregiving demands, caregiver resources and patient characteristics.

Context of care included the caregiver’s age and gender, cohabitation (yes/no), and kin relationship (spouse-partner/other) with the patient.

Caregiving demands were related to the caregiving period (months), hours per week, and caregiver’s burden. Caregiving period and hours per week were measured at the hospital regarding the patient’s pre-exacerbation status and dichotomized as described elsewhere.14,15Burden was measured at the hospital and again 12 weeks after discharge by the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (ZBI),16,17which overload is defined as the extent to which caregivers perceive their emotional or physical health, social life and economic situation as suffering as the result of the care of their relative. The ZBI included 22 items using a 5-point response scale ranging from “never” to “almost always”. Its summative score was categorized into low, moderate, or high burden.

Caregiver resources included help from another caregiver (yes/no) and perceived social support. The latter was measured by the Duke UNC questionnaire, which includes 11 items for measuring affective and confidential support. For this instrument, affective support is defined as receiving tokens of affection and feel loved and understood; confidential support is defined as having someone to talk about concerns or problems, such as having a confidant. These items asked respondents to indicate how they felt using a 5-point response scale ranging from “much less than what I want” to “much as I want”. A summative score was obtained per subscale and categorized as scarce or normal support.18)(19

Patient characteristics were related to illness and associated physiological factors, including airflow limitation, the modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale, frailty, and level of dependence. Airflow limitation was extracted from electronic files on the patient’s last control visit for COPD before hospitalization. Frailty was measured at the hospital by means of the Reported Edmonton Frail Scale based on a scale from 0 to 18, where higher scores indicate more severe frailty.20) Dyspnea and dependence were measured at the hospital and again 3 months after discharge. Dependence was measured by a scale of six activities of daily living (ADLs: toileting, bathing, transferring, eating, dressing, and walking across a small room) as described elsewhere.17Dependence was defined as self-reporting being unable to perform an ADL or requiring the help of another person for any ADL. The range score of this scale (0-6) was based on the number of dependencies, with a score of 6 representing dependencies in all ADLs.

Statistical analysis

Caregivers were classified according to their change in anxiety, non-anxiety, and death from hospitalization to 12 weeks after hospital discharge. Caregivers who had anxious symptoms at baseline and did not have symptoms at the end of the study were classified as being in remission (yes / no). Caregivers who were anxiety free at the hospital and became anxious were categorized as a new episode of anxiety (yes / no).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize variables regarding the context of care, demands, resources, anxiety and patient characteristics for caregivers with and without anxiety symptoms in hospitalization. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to assess the possible factors associated with both remission and a new episode after hospital discharge, which were used as dependent variables. A final multivariate logistic regression model was chosen by including the most strongly predictive factors from each of the individual models, as well as variables significant at the 0.10 level. All multivariate models were produced using the back-step method. Goodness-of-fit and regression diagnostics were assessed as described elsewhere. 21

The sample size calculation was based on the rule of thumb that 15 subjects are needed per predictor for a reliable equation.22) We recruited a minimum of 75 participants assuming a maximum of five predictors. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) statistical software program (SPSS version 19.0; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

During the study period, 90 main caregivers of patients hospitalized for COPD were identified, all agreed to participate in the study, 3 were excluded at baseline because the patient had a hospital stay of more than 30 days. The characteristics of the 87 caregivers and patients are shown in Table II. At 12 weeks 84 continued in the study: 2 died and 1 dropped out of the study because the patient died.

Figure I shows the probability of change between the states of anxiety, non-anxiety and death at 12 weeks after hospital discharge. The arrows represent the probability that a subject who was anxious or not anxious in the hospital remain in that state or change to another state 12 weeks later. Of the 50 subjects with anxiety in the hospital, 22 (44.9%) were anxiety free at 12 weeks after hospital discharge; while 27 (54%) maintained the anxiety state and 1 (2%) died.

On the other hand, 27 (73%) of the caregivers who did not have symptoms of anxiety in the hospitalization were anxiety-free at 12 weeks, 8 (21.6%) became anxious one died and another abandoned due to death of the patient that took care).

At 12 weeks, a total of 35 caregivers (41.66% of the 84 participants) had anxiety symptoms.

In univariate logistic regression analyzes (not shown), only age (p = 0.030), other caregiver help (p = 0.044) and COPD severity (p = 0.008) were associated with remission; While only perceived overload (p = 0.025) and dependence (p = 0.052) were associated with new episodes.

These associated variables were introduced into their respective multivariate model (referral and new episodes as dependent variables). According to the first model, the severity of COPD and not receiving support from another caregiver decreased the likelihood of remission. In contrast, moderately high perceived overload at home increased the likelihood of anxiety after hospital discharge. The results of multivariate models for predictors of remission and new episodes of anxiety of the caregiver 12 weeks after discharge are shown in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Many of the caregivers of COPD patients who present anxiety during their hospitalization return to their anxious state 3 months after discharge, but the likelihood of remission decreases in case of severe COPD or lack of support from another caregiver. The caregiver's perception of moderately high overload increases the likelihood of experiencing anxiety symptoms.

The percentage of caregivers with symptoms of anxiety in the home weeks after hospital discharge (41.66%) was in line with previous studies of carers of patients with stable COPD in the community.14)(15)

The severity of the patient's COPD was a predictor of remission of caregiver anxiety after hospitalization. One possible reason for this latest finding could be that severe illness requires more support in the activities of daily living; Therefore, it is more difficult to decrease the caregiver's stress and anxiety state.23)(24)(25) In fact, another factor associated with anxiety remission after hospital discharge was receiving help from another caregiver. This finding was also expected because caregivers' anxiety status declines when they receive help in managing patient care.26 In addition, the presence of an informal support network in care is shown to be a protective factor that reduces the degree of fatigue in informal caregivers of immobilized patients.27

Caregiver overload was a predictor both at the time of hospitalization and in the appearance of new episodes of anxiety after hospital discharge. The results of our study are consistent with an earlier study that the number of supervised tasks is predictive of various mental health outcomes in the caregiver, including anxiety and stress.28 In addition, other studies show that caregivers of patients with treatments that require mechanical ventilation, that patients may undergo after an acute exacerbation of COPD, are at risk of overload and anxiety after discharge. However, it was not found to be a protective factor against this psychological problem. One possible explanation for the results of previous studies is that caregivers may experience this burden after hospital discharge because of frustration because they handle all care with less support than in the institutional setting.29 This is consistent with studies in the caregivers of patients with acute COPD exacerbation experience greater overload in home programs where they have to assume an increase in activities relative to conventional hospitalization could relieve caregivers of some of the tasks.8

Although health policies call for collaboration between formal and informal caregivers, services focus primarily on the patient. As a result, professionals have the risk of excluding family caregivers.30 Any program, strategy or policy for health promotion and care for people with disabilities can not overlook the importance of family support.2 However, on the needs of caregivers of patients with COPD, there are unknown aspects that may prevent the development of effective interventions for this population.4 Returning home after the hospitalization of a COPD patient will require interventions that facilitate the collaboration of other carers and mechanisms to reduce the perception of overload of the principal caregiver.

Limitations of the study

These results should be interpreted considering the methodological limitations of the study. It was not possible to know the anxiety of the caregiver prior to hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD. Longitudinal studies evaluating anxiety and premorbid health status before hospitalization would be desirable. It would be desirable to assess the caregiver's relationship with the patient since a poor prior relationship can interfere with the outcome. The state of anxiety after hospital discharge was measured only once at 12 weeks, and there may be fluctuations between these times. In addition, the recovery time may be longer. Therefore, our results are likely to underestimate recovery rates. Finally, due to the number of men in this cohort is small, we must be cautious in generalize the results to men.

CONCLUSIONS

This study advances current knowledge regarding anxious symptoms among caregivers during hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD, the perception of anxious symptoms is dynamic and many caregivers will not experience anxious symptoms within 12 weeks after discharge. Caregivers are likely to recover from anxiety when they receive help from another caregiver and if their patients do not have severe COPD. Further research should address the caregivers’ needs, especially the effectiveness of supportive interventions to prevent distress in hospitalization.

REFERENCIAS

1. Miravitlles M, Cantoni J, Naberan K. Factors associated with low level of physical activity inpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lung. 2014;192:259-65. [ Links ]

2. Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J, Hidalgo-Vega Á, Miravitlles M. Economic valuation and determinants of informal care to disabled people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:101. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4373101/ [ Links ]

3. Ko FW, Chan KP, Hui DS, Goddard JR, Shaw JG, Reid DW, Yang IA. Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21:1152-65. Disponible en: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/resp.12780/epdf [ Links ]

4. Mansfield E, Bryant J, Regan T, Waller A, Boyes A, Sanson-Fisher R. Burden and unmet needs of caregivers of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients: A systematic review of the volume and focus of research output. COPD. 2016;13:662-7. Disponible en: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/15412555.2016.1151488 [ Links ]

5. Nakken N, Janssen DJ, van den Bogaart EH, Wouters EF, Franssen FM, Vercoulen JH, Spruit MA. Informal caregivers of patients with COPD: home sweet home? Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24:498-504. Disponible en: http://err.ersjournals.com/content/24/137/498.long [ Links ]

6. Miravitlles M, Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J, Hidalgo-Vega Á. Caregivers' burden in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:347-56. Disponible en: https://www.dovepress.com/caregiversrsquo-burden-in-patients-with-copd-peer-reviewed-article-COPD [ Links ]

7. Grant M, Cavanagh A, Yorke J. The impact of caring for those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on carers' psychological well-being: a narrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:1459-71. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0052462/ [ Links ]

8. Utens CM, van Schayck OC, Goossens LM, Rutten-van Mölken MP, DeMunck DR, Seezink W, van Vliet M, Smeenk FW. Informal caregiver strain, preference and satisfaction in hospital-at-home and usual hospital care for COPD exacerbations: results of a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51:1093-102. [ Links ]

9. Bernabeu-Mora R, García-Guillamón G, Montilla-Herrador J, Escolar-Reina P, García-Vidal JA, Medina-Mirapeix F. Rates and predictors of depression status among caregivers of patients with COPD hospitalized for acute exacerbations: a prospective study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:3199-205. Disponible en: https://www.dovepress.com/rates-and-predictors-of-depression-status-among-caregivers-of-patients-peer-reviewed-article-COPD [ Links ]

10. Göris S, Klç Z, Elmal F, Tutar N, Takc Ö. Care Burden and Social Support Levels of Caregivers of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Holist Nurs Pract 2016;30:227-35. [ Links ]

11. Costa X, Gómez-Batiste X, Pla M, Martínez-Muñoz M, Blay C, Vila L. Vivir con la enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica avanzada: el impacto de la disnea en los pacientes y cuidadores. Aten Primaria. 2016;48:665-73. Disponible en: http://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-atencion-primaria-27-resumen-vivir-con-enfermedad-pulmonar-obstructiva-S021265671630097X [ Links ]

12. Goldberg D, Bridges K, Duncan-Jones P, Grayson D. Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ. 1988;297:897-9. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1834427/ [ Links ]

13. Montón C, Pérez-Echevarría MJ, Campos R, García Campayo J, Lobo A. Anxiety scales and Goldberg's depression: an efficient interview guide for the detection of psychologic distress. Aten Primaria. 1993;12:345-9. [ Links ]

14. Jácome C, Figueiredo D, Gabriel R, Cruz J, Marques A. Predicting anxiety and depression among family carers of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:1191-9. [ Links ]

15. Figueiredo D, Gabriel R, Jácome C, Cruz J, Marques A. Caring for relatives with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: how does the disease severity impact on family carers? Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:385-93. Disponible en: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13607863.2013.837146 [ Links ]

16. Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist. 1986;26:260-6. [ Links ]

17. Garlo K, O'Leary JR, Van Ness PH, Fried TR. Burden in caregivers of older adults with advanced illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2315-22. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3058825/ [ Links ]

18. Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNK Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26:709-23. [ Links ]

19. Bellón Saameño JA, Delgado Sánchez A, Luna del Castillo JD, Lardelli Claret P. Validity and reliability of the Duke-UNC-11 questionnaire of functional social support. Aten Primaria. 1996;18:153-63. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8962994 [ Links ]

20. Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S, Murnion BP, Dent J, Bajorek B, Matthews S, Rolfson DB. The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28:182-8. [ Links ]

21. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [ Links ]

22. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2013. [ Links ]

23. Hudson PL, Aranda S, Kristjanson LJ. Meeting the supportive needs of family caregivers in palliative care: challenges for health professionals. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:19-25. Disponible en: http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/109662104322737214 [ Links ]

24. McClendon MJ, Smyth KA, Neundorfer MM. Survival of persons with Alzheimer's disease: caregiver coping matters. Gerontologist. 2004;44:508-19. Disponible en: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.494.1147&rep=rep1&type=pdf [ Links ]

25. Cruz J, Marques A, Figueiredo D. Impacts of COPD on family carers and supportive interventions: a narrative review. Health Soc Care Community 2017;25:11-25. [ Links ]

26. Simpson AC, Rocker GM. Advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact on informal caregivers. J Palliat Care. 2008;24:49-54. [ Links ]

27. Peña-Ibáñez F, Álvarez-Ramírez M, Melero-Martín J. Sobrecarga del cuidador informal de pacientes inmovilizados en una zona de salud urbana. Enfermería Glob. 2016;15:100-11. Disponible en: http://revistas.um.es/eglobal/article/viewFile/212541/194621 [ Links ]

28. Caress AL, Luker KA, Chalmers KI, Salmon MP. A review of the information and support needs of family carers of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:479-91. [ Links ]

29. Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, O'Toole E, Montenegro H. Impact of a disease management program upon caregivers of chronically critically ill patients. Chest. 2005;128:3925-36. [ Links ]

30. Aasbø G, Rugkåsa J, Solbraekke KN, Werner A. Negotiating the care-giving role: family members' experience during critical exacerbation of COPD in Norway. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:612-20. [ Links ]

Received: January 16, 2017; Accepted: April 05, 2017

texto en

texto en