My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Enfermería Global

On-line version ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.17 n.49 Murcia Jan. 2018 Epub Dec 14, 2020

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.16.4.276061

Originales

Childbirth expectations of La Ribera pregnant women: a qualitative approach

1Enfermera especialista en Obstetricia y Ginecología (Matrona). Doctoranda del programa de Doctorado en Enfermería clínica y comunitaria de la Universidad de Valencia. Matrona asistencial en el paritorio del Hospital Universitario de La Ribera. Alzira. Valencia. España.

2Enfermera especialista en Obstetricia y Ginecología (Matrona). Matrona asistencial en el paritorio del Hospital Universitario de La Ribera. Alzira. Valencia. España

Objective

Change of healthcare model in normal childbirth, health authorities interest in exploring childbirth expectations of pregnant women, and their cultural and social specificity make relevant the study of these expectations at this moment. The aim is to know what are the childbirth expectations from a sample of Spanish pregnant women and to study the differences between primiparous and multiparous pregnant women expectations.

Methodology

Qualitative study based on an open-ended question about childbirth expectations. Data were collected during 2014-2015 to third trimester pregnant women in La Ribera health area (Alzira, Valencia). Data were analyzed using content analysis.

Results

Sample of 213 pregnant women whose main expectations were to have a fast delivery, with good obstetric outcome, painlessly and with professional support. Expectations regarding normal childbirth protocols accounted for 5.2% of total responses. No statistically significant differences between primiparous and multiparous pregnant women were found.

Conclusions

Knowledge about childbirth expectations is highly relevant because pregnant women measure their satisfaction with childbirth through the fulfillment of these expectations. Helping them to develop realistic expectations will increase their satisfaction. Midwives play an important role through the training they give (maternal education) and through the support during delivery (this is essential for the pregnant women in order to feel themselves protagonist of their delivery).

Keywords childbirth expectations; qualitative research; pregnancy; nurse midwives

INTRODUCTION

Childbirth is a complex life event for every woman, characterized by rapid biological, social and emotional transitions, influenced by contextual, political and, above all, cultural factors1. Many women have come to see the experience of childbirth as a critical moment of self-affirmation and a central element to maternal psychological well-being2. A negative birthing experience can lead to feelings of frustration and lack of control, and affect the woman's decision about future motherhood3)(4.

Forming expectations for major life events can help one prepare mentally or physically for that moment5. Women use these expectations as a benchmark to evaluate their birth experience3)(6. Therefore, women’s satisfaction with childbirth experience depends, to a great extent, on their concordance with previous expectations4)(7)(9.

Besides, such expectations play a role in how women respond and adapt to motherhood4)(10. The dissonance between expectations and birth experience can lead to damaging the woman’s self-confidence as a mother and to playing a role in risk of postpartum depression5. Pregnant women approach their upcoming birth experience with predetermined and detailed expectations3)(8, which can differ significantly from one another and they are developed over time10. In addition, women’s expectations can be coloured by societal expectations that influence their sense of what is appropriate behavior during childbirth and, due to their cultural and social specificity, it’s difficult to generalize them3.

The concept of childbirth expectations is very widespread in previous literature. However, there is a lack of consensus on their definition11. According to Ayers12, childbirth expectation is a complex and multidimensional construct involving many aspects of childbirth and, in this context, relative to childbirth, it could be defined as “judgments and beliefs about the future that can be influenced by past situations13.

Much of the research in this field, since the last century, have focused on the study of the relationship between expectations and childbirth experiences3)(8)(14)(15)(16 or on the analysis of the childbirth experiences6)(17. In some cases, expectations have been explored after delivery, from 48-72 hours postpartum to several months, and even years after delivery 3)(7)(8)(16)(18. However, it has been more usual to explore them during the third trimester of pregnancy5)(8)(9)(10)(19)(20)(21)(22, at which time expectations have already been developed, due to the closeness of delivery, but have not had a proper delivery experience.

As for the relationship between childbirth expectations and other variables, the analysis highlights the differences between women who have given birth before and those who have had no previous experience of childbirth. According to Peñacoba19, there is extensive knowledge about expectations among women who have not given birth, but there are fewer studies that have explored the expectations of those women who have given birth previously or the difference between the two groups. Thus, some studies find that childbirth expectations are more positive in the case of multiparous than in the primiparous7)(23.

Regarding the type of study, quantitative studies are based on different measuring instruments, like Chilbirth Expectations Questionnaire (CEQ), Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire (W-DEQ) or Expectations of the Childbirth Experience (ECBE)9)(14. Meanwhile, qualitative studies are based on aspects as content analysis7)(20, phenomenological approach8, constant comparison3)(18 and focus groups16)(17. Qualitative studies are particularly suitable for studying complex phenomena or processes that are poorly understood. Among the advantages of qualitative approach, there are, on the one hand, the analysis of a data set without assumptions or generated theories in advance24 and, on the other hand, the fact that “qualitative approach was chosen as most appropriate for the determination of an individual’s feelings, interactions, perceptions and behaviours”25.

In recent years a change in the healthcare system has been taking place, from a biomedical approach to a more psychosocial one, which takes into consideration women’s beliefs and emotions19 and their claims for women’s empowerment26. In this context of change, the study of childbirth expectations takes on a new meaning. Different institutions refer to the importance of professionals` knowledge expectations of every woman regarding the childbirth process as well as the importance of investigating effective ways in which health professionals can support pregnant women to make decisions during childbirth27. In the same line, different studies emphasize both the importance of exploring expectations and health demands of users for inclusion in the supply of healthcare system as well as the insufficient knowledge of the expectations regarding the humanization of childbirth assistance21.

The literature regarding Spain shows that we do not have enough knowledge of childbirth expectations of pregnant women. This knowledge gap is even more important in the case of studies carried out with qualitative methodology. Although there are qualitative studies examining the experience of childbirth by the focus group technique in our country16)(17, there are not qualitative studies examining the expectations prior to childbirth. Thus, we find three important factors:

- change of healthcare model in normal childbirth

- cultural and social specificity of childbirth expectations

- the scarcity of studies that explore the childbirth expectations of pregnant women in Spain from a qualitative approach

Therefore, it is now relevant to approach the childbirth expectations of pregnant women from a qualitative point of view, due to the adequacy of this methodology for the study of feelings and perceptions. Thus, the aim of this research is to carry out a qualitative approach to the study of childbirth expectations of a sample of Spanish pregnant women. Also, a secondary objective is to make a comparison between primiparous and multiparous pregnant women’s expectations.

METHODOLOGY

The study was based on an open-ended question: “What are your childbirth expectations? What do you wish for or expect at birth?" The question was part of a larger questionnaire, as has been done in previous research7)(18)(20. Data were collected between June 2014 and January 2015 from pregnant women in their third trimester of pregnancy at La Ribera University Hospital (Alzira, Valencia) who attended gynecology emergency doors or fetal well-being control examination rooms.

Inclusion criteria were pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy, over 18 years old, who were able to express themselves without difficulty in any of the two official languages (Spanish or Valencian) and who agreed to be included in the study. Women who did not meet these criteria were excluded from the study. A convenience sample was used, usual in such studies, both qualitative7)(8)(18)(21 and quantitative8)(19)(22. A pilot questionnaire was passed on to a small group of pregnant women (10 women, as Fenwick did18, being the usual piloting between 520 and 20 women7). Finally, it was approved by the Quality Service of La Ribera University Hospital.

The following study variables were collected:

- Age expressed in years, categorical variable grouped in 3 intervals (from 18 to 25, from 26 to 35 and older than 35 years)

- Education level, categorical variable with 4 categories (without studies, primary studies, secondary studies and university studies)

- Obstetrical formula, dichotomous categorical variable (primiparous or multiparous)

- Belonging to the health area of La Ribera, categorical dichotomous variable (within the health area or not)

- Assistance to childbirth preparation activities (categorical dichotomous yes/no)

- Childbirth expectations, open-ended question on which a content analysis was performed

The content analysis was conducted by a procedure similar to that performed in other qualitative studies on this subject7)(8)(18)(25, which consists of the following steps24:

- Transcribing the answers and making a reading

- Identifying common themes

- Codifying the data to reduce them to concepts

- Structuring concepts into categories and subcategories

In order to increase the reliability of the data analysis, they were coded by the 2 researchers separately5)(25 and finally compared, discussed and re-evaluated to create shared codes and categories24. Similarly to other studies18)(20, participants gave more than one answer to the question of what were their childbirth expectations. The total number of responses for each category was quantified in an Excel spreadsheet, along with the sociodemographic data obtained. Statistical treatment was performed with the Statistical Program of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0. As all categorical variables, the comparison of the variables was performed using the Pearson Chi-square test for categorical variables (statistical significance level p<0.05 for bilateral tests). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee-Research Commission of La Ribera University Hospital in June 2014. No pregnant women refused to participate in the study and all women gave their informed consent.

RESULTS

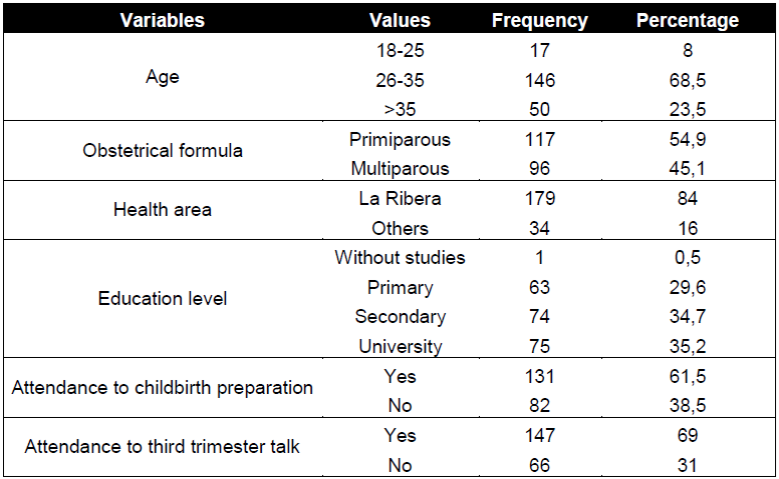

A total sample of 213 pregnant women who met the inclusion criteria was collected, whose socio-demographic data are reflected in Table I. A total of 422 coded responses were obtained, including cases in which the pregnant woman stated that she had no childbirth expectation (n = 11), as shown in Figure 1. The responses were coded into 7 categories (Figure 1) and 4 subcategories.

Within the category "support", subcategories "professional support " (n = 47) and "support provided by the person chosen as a companion" (n = 18) were included. The category "relative to type of delivery" included subcategories "have a normal/vaginal birth" (n = 54) and "performing elective cesarean section" (n = 3).

As for the comparison according to the variable “obstetrical formula”, 57% (n = 239) of the answers were provided by primiparous women and 43% (n = 183) remaining by multiparous women (Table II).

Table II Frequency distribution and childbirth expectations percentages based on the variable “obstetrical formula”

Statistical analysis showed no statistically significant relationship, in any of the categories, between the childbirth expectations of the primiparous and multiparous women in the sample. Nevertheless, the data suggest some trends, such as the higher frequency of expectations regarding normal childbirth care protocols in primiparous women compared to multiparous women.

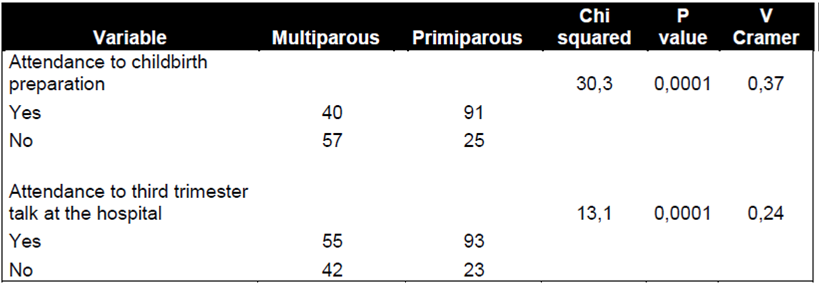

Furthermore, in relation to the variable “obstetrical formula” and the attendance to programmed activities for the maternal education (childbirth preparation and third trimester talk at the hospital), a statistically significant relationship has been found (Table III). In this case, primiparity is associated with increased attendance to both types of prenatal training activities.

DISCUSSION

The exploration of the childbirth expectations of a sample of Spanish pregnant women has allowed, on the one hand, to classify such expectations into 7 categories and 4 subcategories and, on the other hand, to verify the non-existence of statistically significant differences between the expectations of primiparous and multiparous women. This lack of differences differs from the results of other studies, which do detect differences between them, finding among multiparous women a more positive childbirth expectation7)(23 and lower scores on pain expectation19. There are several possible explanations for this difference, from the adaptation of current expectations based on previous experience3)(7)(23 to the probability that women with previous negative experience do not have other pregnancies23. With due precautions, our results would support that we can work with samples of multiparous women alone7)(18 as well as primiparous women alone8)(9)(20)(25. According to the above, where the differences are detected, they may not be related to parity, but with other explanatory factors. For example, Tarkka6 states that women with a more positive attitude are more likely to have a positive birth experience. According to this, we could say that maternal attitude could be one of those explanatory factors.

Despite not having found statistical significance, there are, however, remarkable tendencies, such as more frequent expectations regarding care protocols to normal childbirth among primiparous women (Table II). This is just one aspect that has recently been introduced in childbirth care at La Ribera University Hospital. This higher frequency may be related to the attendance of the primiparous women to childbirth preparation training activities (in which they are informed of the recently introduced protocols), aspect that does present statistical significance in the present study (Table III).

Regarding the classification into 7 categories, the childbirth expectation with the highest frequency was "having a fast delivery" (n = 106). In the case of quantitative studies, it is expressed through the item "I hope this labor will go smoothly, normally and fast" of the CEQ19) and an item of the ECBE, where it is expressed negatively (having a very long childbirth), appearing in 66% of the surveyed pregnant women9. It is also reflected in some qualitative studies 8)(18, being one of the most important expectations in the research carried out by Gibbins8, as in the present study. Expecting a fast or easy delivery is understood as an unrealistic or idealized expectation, according to Beaton10, and the starting point for having a disappointment with the subsequent birth experience.

The other major category obtained by Gibbins8, "labor pain", appears in third place (n = 70) in this case. Most of the qualitative studies5)(7)(8)(18)(20)(25, as well as some quantitative ones that use the CEQ as a tool9, collect this category. In contrast, in other quantitative studies using the same questionnaire it is not collected between the highest expectations. Thus, for Peñacoba19, “labor pain” is only important for 20% of pregnant women, and Zhang22 shows that 68% of pregnant women wanted to adopt non-pharmacological pain relief methods, without specific reference to “labor pain” as expectation.

Safety and health of both mother and baby is the second expectation in terms of frequency (n = 82) and has been categorized as "having a good obstetric outcome". It has been found in most of the qualitative studies consulted 5)(7)(8)(18)(20)(25, being absent in most quantitative studies9)(22; Peñacoba’s study19 is an exception. The fact that it appears regularly in qualitative studies and hardly ever in quantitative studies could be interpreted as a failure in questionnaires in capturing this issue.

Referring to the "support" category, which has been divided into two subcategories (professional support and companion support), the results indicate that professional support has a much greater weight than companion support. This result is consistent with other studies where professional support is the most significant for improving the experience of women during childbirth4)(6)(15, while companion support is also important, but does not show the same positive effect28. In addition, there are studies showing an association between professional support and shorter duration of delivery28, and even support from midwives is able to motivate women who have had a bad experience during the childbirth seek a future pregnancy7. In different qualitative approaches, pregnant women express their fears about three aspects: the quality of the care that they could receive from professionals25; the possibility of being poorly treated by them7)(9)(20; and the importance of being treated individually7)(18.

However, in quantitative studies, companion support has a greater weight than professional support19,22,29. This discrepancy between the results of qualitative and quantitative studies could be explained by the difference in the number of items that refer to companion support and professional support in the questionnaires. In this context, the interest and usefulness of qualitative methodologies for the study of childbirth expectations is clear, because presumptions or theories generated beforehand are avoided24.

On the other hand, with respect to professional support, different studies highlight the importance of the figure of the midwife and the power they exert over women during childbirth30. Thus, these labor professionals are a great source of information, and physical and emotional support, besides the technical role that is expected of them5. Midwives should use this power sensitively and intelligently to achieve the greatest benefit for the woman in their charge, taking the time to discuss the expectations of pregnant women and to ensure their realism and relevance5.

Expectations "relative to type of delivery" are subdivided into 2 categories, those pregnant women who wish to have a "normal" or "vaginal" birth (n = 54, expressed in their own words, just as it happens in other studies, where both terms are used indistinctly18), and those who wish to have an elective caesarean section (n = 3). This interest in having a normal birth appears in qualitative studies where the pregnant women are sensitized towards the humanized childbirth20)(21 (both studies conducted in Brazil, where there is an important movement for the humanization of childbirth). In addition, it is the most important expectation (n = 112), together with a fast delivery, in the study conducted by Fenwick18 in Australia. In quantitative studies, the interest in the type of delivery is included within the item "I hope this labor will go smoothly, normally and fast", being one of the greatest expectations of Peñacoba’s study in Spanish pregnant women19.

The present study has differentiated between the “having a normal delivery" expectation and all those included within the "normal childbirth care protocols". The latter have had a low frequency, probably because of their recent introduction into the healthcare model. However, in other studies it is difficult to differentiate whether pregnant women expressing their desire to have a normal delivery refer simply to vaginal delivery (as interpreted by Fenwick)18, or to aspects related to normal childbirth care protocols. In this study, Fenwick's interpretation18 was followed.

Finally, the need for "information and control" is the category with the lowest rate (n = 9). Referring to other studies, it has only been found in the study performed by Fenwick18, which presents it as a subcategory within the category "involvement and participation in the birthing experience". Another qualitative research refers to control like confidence in the care provided by health professionals5. However, the sense of control provided by the information is considered very important in some studies, in order to face the experience of childbirth positively, even when childbirth experience does not meet prior expectations8. Therefore, information is emerging as a key element to generate more precise and specific expectations3)(15.

Health professionals in general, and midwives in particular, are an excellent source of information, especially in countries where there exists the opportunity to attend childbirth preparation classes or maternal education 9)(15)(18. Consequently, health professionals should be aware of the supplementary sources of information their patient use (especially if they are not attending childbirth education) and offer validate resources when necessary5.Due to the high interest on this topic, it should be raised as a future line of research, focusing, firstly, on the exploration of the different sources of information that the pregnant women manage, and, secondly, on the origin of the information (contrasting the information provided by midwives and other health professionals with other potential sources of additional information).

CONCLUSIONS

The knowledge of the childbirth expectations of pregnant women is a crucial facet to provide the best possible health care during delivery, adapting the childbirth experience of pregnant women to their expectations in order to achieve the highest degree of satisfaction with the birthing process. In the current moment of a changing healthcare model, it is still more necessary to know the childbirth expectations of pregnant women, since the humanized delivery care model implies that women make decisions about their birth process and insists on the concept of communication between users and health professionals.

The qualitative approach to the study of childbirth expectations from a sample of Spanish pregnant women has allowed to classify them into 7 categories (fast delivery, relative to pain, good obstetric outcome, support, relative to type of delivery, information and control, and relative to normal childbirth care protocols), with no statistically significant differences between the expectations expressed by primiparous and multiparous pregnant women.

Among the most important expectations are those related to having a fast delivery, with a good obstetrical outcome, and painless. However, expectations related to normal childbirth care protocols have a scarce presence, possibly due to the recent introduction of this healthcare model. It also highlights the importance of the support provided by health professionals, in particular the midwife, as the main actor in order to align expectations and childbirth experiences of pregnant women. The midwife is the most suitable professional to provide pregnant women with quality information on issues related to pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood, collaborating significantly in developing realistic expectations and in the empowerment of the pregnant woman on the decision-making on issues that affect them.

It is considered interesting as a future research line to explore different sources of information that influence the generation of childbirth expectations of pregnant women, as well as the role of the information provided by health professionals dedicated to the childbirth care.

REFERENCIAS

1. Pinheiro BC, Bittar, CML. Expectativas, percepções e experiências sobre o parto normal: Relato de um grupo de mulheres. Fractal Revista de Psicologia. 2013;25(3):585-602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-02922013000300011 [ Links ]

2. Soet JE, Brack GA, DiIorio C. Prevalence and predictors of women's experience of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth. 2003;30:36-46. [ Links ]

3. Hauck Y, Fenwick J, Downie J, Butt J. The influence of childbirth expectations on western Australian women's perceptions of their birth experience. Midwifery. 2007;23,235-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2006.02.002. [ Links ]

4. Green JM, Baston HA. Feeling in control during labor: concepts, correlates, and consequences. Birth. 2003;30:235-247. [ Links ]

5. Martin DK, Bulmer SM, Pettker CM. Childbirth expectations and sources of information among low- and moderate- income nulliparous pregnant women. J Perinat Educ. 2013;22(2):103-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.22.2.103 [ Links ]

6. Tarkka MT, Paunonen M, Laippala P. Importance of the midwife in the first-time mother's experience of childbirth. Scand J Caring Sci. 2000;14(3):184-190. [ Links ]

7. Rilby L, Jansson S, Lindblom B, Mårtensson LB. A Qualitative Study of Women's Feelings About Future Childbirth: Dread and Delight. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2012;57(2):120-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00113.x. [ Links ]

8. Gibbins J, Thomson AM. Women's expectations and experiences of childbirth. Midwifery. 2001;17(4):302-313. [ Links ]

9. Oweis A, Abushaikha L. Jordanian pregnant women's expectations of their first childbirth experience. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004;10(6):264-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172x.2004.00488.x. [ Links ]

10. Beaton J, Gupton A. Childbirth expectations: a qualitative analysis. Midwifery. 1990;6(3):133-139. [ Links ]

11. Christiaens W, Verhaeghe M, Bracke P. Childbirth expectations and experiences in Belgian and Dutch models of maternity care. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2008;26(4):309-322. [ Links ]

12. Ayers S, Pickering AD. Women's expectations and experience of birth. Psychol Health. 2005;20(1):79-92. [ Links ]

13. Sweeny K, Krizan Z. Sobering up: A quantitative review of temporal declines in expectations. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(3):702-724. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029951. [ Links ]

14. Gupton A, Beaton J, Sloan J, Bramadat I. The development of a scale to measure childbirth expectations. Can J Nurs Res. 1991;23(2):35-47. [ Links ]

15. Lally JE, Murtagh MJ, Macphail S, Thomson R. More in hope than expectation: A systematic review of women's expectations and experience of pain relief in labour. BMC Medicine. 2008;6:7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-6-7. [ Links ]

16. Ferreiro-Losada MT, Díaz-Sanisidro E, Martínez-Romero MD, Rial-Boubeta A, Varela-Mallou J, Clavería-Fontán A. Evaluación mediante grupos focales de las expectativas y percepciones de las mujeres durante el proceso de parto. Rev Calid Asist. 2013;28(5):291-299. [ Links ]

17. Goberna Tricas J, Palacio Tauste A, Banús Giménez MR, Linares Sancho S, Salas Casas D. Tecnología y humanización en asistencia al nacimiento. La percepción de las mujeres. Matronas Prof. 2008;9(1):5-10. [ Links ]

18. Fenwick J, Hauck Y, Downie J, Butt J. The childbirth expectations of a self-selected cohort of Western Australian women. Midwifery. 2005;21(1):23-35. [ Links ]

19. Peñacoba-Puente C, Carmona-Monge FJ, Marín-Morales D, Écija-Gallardo C. Evolution of childbirth expectations in Spanish pregnant women. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:59-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2015.05.017 [ Links ]

20. Almeida N, Fleury EM. Expectativas de Gestantes sobre o Parto e suas Percepções acerca da Preparação para o Parto. Temas em Psicologia. 2016;24(2):681-693. http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.2-15 [ Links ]

21. Basso JF, Monticelli M. Expectativas de participação de gestantes e acompanhantes para o parto humanizado. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2010;18(3):97-105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692010000300014 [ Links ]

22. Zhang X, Lu H. Childbirth expectations and correlates at the final stage of pregnancy in Chinese expectant parents. International Journal of nursing sciences. 2014;(1):151-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2014.05.019 [ Links ]

23. Wijma K, Söderquist J, Wijma B. Posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth: A cross sectional study. J Anxiety Disord. 1997;11(6):587-597. [ Links ]

24. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105-112. [ Links ]

25. Serçekus P, Okumus H. Fears associated with childbirth among nulliparous women in Turkey. Midwifery. 2009;25(2):155-162. [ Links ]

26. Biurrun-Garrido A, Goberna-Tricas J. La humanización del trabajo de parto: necesidad de definir el concepto. Revisión de la bibliografía. Matronas Prof. 2013;14(2):62-66. [ Links ]

27. National Collaborating Centre for Women´s and Children´s Health. Intrapartum Care. Care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. Clinical Guideline 190. Methods, evidence and recommendations; 2014. Disponible en: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG190 (último acceso 22 de noviembre 2016). [ Links ]

28. McGrath SK, Kennell JH. A randomized controlled trial of continuous labor support for middle-class couples: effect on cesarean delivery rates. Birth. 2008;35(2):92-97. [ Links ]

29. Udofia EA, Akwaowo CD. Pregnancy and after: What women want from their partners listening to women in Uyo, Nigeria. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;33(3):112-119. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/0167482X.2012.693551. [ Links ]

30. Anderson T. Feeling safe enough to let go: the relationship between a woman and her midwife during the second stage of labor. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2000. [ Links ]

Received: November 24, 2016; Accepted: April 07, 2017

text in

text in