Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.17 no.51 Murcia Jul. 2018 Epub 01-Jul-2018

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.17.3.276101

Originals

Student nurse perceptions of supervision and clinical learning environment: a phenomenological research study

1 Profesor/a Asociado. Departamento de Enfermería. Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud. Universidad de Alicante. Alicante, España. flores.vizcaya@ua.es

2 Profesor de Biología celular. Departamento de Biotecnología. Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad de Alicante. Alicante, España.

Aim.

To analyse nursing students' perceptions of the supervision relationship and the clinical learning environment during their clinical practice placements.

Methods.

A qualitative design was used to conduct this phenomenological study. Data were collected through semi-structured focus group interviews. The purposive sample consisted of 48 nursing students of the University of Alicante (Spain). Semi-structured focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim and then analysed using the stage by stage method. A tree structure with four categories arose: individualization, innovation in clinical teaching, student participation, and nurse tutor-student nurse relationship individual training.

Results.

This study shows that no individualization is involved in the clinical learning process. Student participation in ward activities depends on the student's experience, the characteristics of the ward, the nursing team and the nurse tutor. Students feel that the role of the nurse tutor is not clearly defined. Anxiety, vulnerability and feelings of being "temporary workers" are common in nursing students.

Conclusions.

These results should prompt to deeper reflections on the studied elements of the supervisory process and the clinical learning environment. More specifically on aspects of individualization, student participation, and feelings, but also in the clarification of the tutor role definition.

Keywords: Clinical learning environment; Student supervision; Nursing education; Qualitative research; Nursing

INTRODUCTION

Many authors have approached the learning environment concept from different perspectives1)(2)(3)(4. Hiemstra5) stated that the learning environment represents multiple things to students. As well as the physical atmosphere, it also provides psychological and emotional conditions and the social or cultural influences that affect the growth and development of the learning process. Similarly, Knowles6 stated that the concept of the learning climate highlights the importance of physical, human, interpersonal and organizational characteristics, and mutual respect and trust between teachers and students. Fraser4 expanded on these ideas, describing science learning environments. And recently, the concept and methodology have also been review by Clevenland and Fisher7.

When addressing the concept of the learning environment, it should be remembered that nursing is essentially a practice-based profession, so clinical practice placements in health institutions are an essential component of the undergraduate student curriculum 8)(9)(10. By the Bologna Declaration and with the European Directive, the clinical training component of a nursing degree in Spain now accounts for a minimum of 90 ECTS (11). Clinical placements are distributed throughout the degree course, although more are undertaken during the third and fourth academic years12). As a result, of these recent changes, in-depth studies of the characteristics of the clinical environment could be of interest to nursing educators.

Background

In nursing education context the concept of Clinical Learning Environment (CLE) has been defined as interactive network or set of characteristics inherent to the practices that influence learning outcomes and professional development nurse13)(14. Thus the internship position, offers students optimal scenarios to observe models and reflect on what is seen, heard, it is perceived or made15)(16, thus is generated and guides the professional socialization process of the student17.

According to previous literature, Flott and Linden16 explain that the CLE concept encloses four attributes that influence student learning experiences: the physical space, the psychosocial and interactions factors, the organizational culture, and the elements of the teaching-learning process. That is, the clinical learning environment is the "clinical classroom" with a complex social climate in which students, nurses, teachers and patients interact18.

Therefore, a cultural understanding of the CLE should be reflected in the nursing curriculum in higher education in the international context 16)(19)(20. In this line, the Erasmus programme has facilitated clinical training for student nurses some at universities around Europe21. Furthermore, a need has been identified to define areas of competence in the context of European nursing education 22. Given the importance of the CLE, understanding how it is perceived by students and how it influences their learning process becomes relevant. Most of the previous studies on learning environment use a quantitative methodology, and the ones that approach students’ perceptions from the qualitative perspective are less.

METHODS

Aim

The aim of this study is to determine how a sample of Spanish nursing students perceives the CLE in which they undertake their practice placements.

Design

A qualitative design was used to research this phenomenological study. Through the results of this study, it is not possible to make generalizations, but we can understand the individual characteristics and experience of these students during their clinical practices. For this reason, an interpretive phenomenological approach based on the understanding of experiences, and the articulation of similarities and differences in the meanings and experiences of human beings23, can be the most appropriate one for achieving the objectives.

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) was used to improve the quality of reporting of the present study 24.

Sample and setting

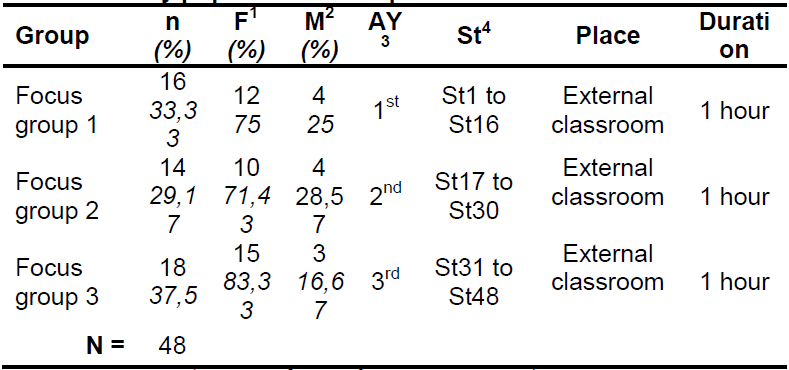

The participants were the total of students from the University of Alicante (Alicante, Spain) that performed their clinical practice placements at the University Hospital of San Juan de Alicante in May 2012. Neither of them refused or dropped out of the study. The purposive sample consisted of 48 students (Table 1).

Table 1 Study population description and data collection context.

Legend: 1Female; 2Male; 3Academic year; 4Student codes.

As in previous research in Spanish context 25)(26, the students in this study identified the roles of “nurse tutor”, “nurse” and “ward manager” as members of the supervision team in the ward context. Centring on the roles, while a nurse tutor is a nurse who has been assigned 2-4 students and is directly responsible for their learning and evaluation, a nurse has no designated student, but occasionally participates in a learning activity.

Data collection

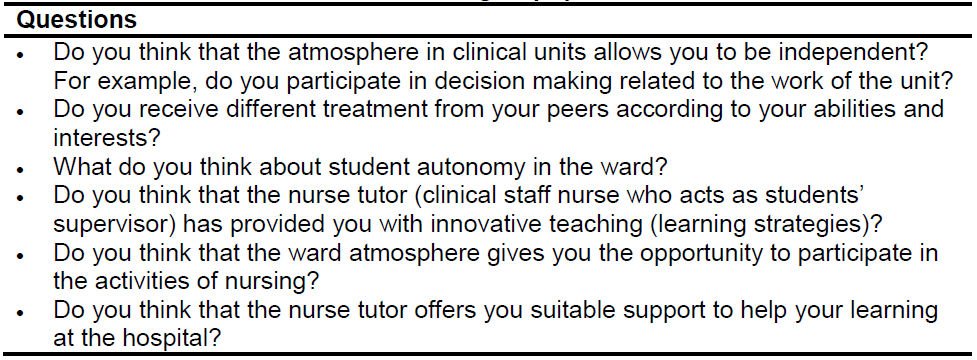

Data were collected by three semi-structured focus group interviews that were conducted during a weekly clinical session, and recorded in audio format (Table 1). Two of the researchers were presented during the focus group interviews. While one of them was conducting the session, the other one made field notes. Table 2 lists all the focus group interview questions.

Ethical considerations

This study has adhered to the ethical requirements governing researcher and teacher responsibilities27 and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Alicante.

During the transcription of the interviews, “St” codes were used for referencing all participating.

Data analysis

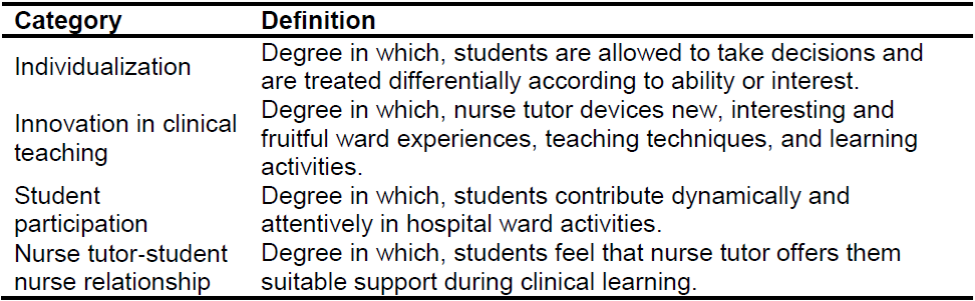

Semi-structured focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim, and then analysed using the “stage by stage” method28. This process of analysis consisted of the following steps: 1) labelling the data and establishing a data index, 2) categorizing the content of the data into meaningful categories, and 3) determining a mutually agreed category list of themes (Table 3). The QSR NUD*IST 5 software was used for these analyses to categorise qualitative data.

Rigour

We performed an interview triangulation (second interviewer) during focus group interviews and an investigator triangulation in the analysis process. Students were given a transcript of the interview upon completion and asked to verify that the information was correct (corroborating findings).

RESULTS

The interviews were transcribed and codified according to the different interviews questions (Table 2), creating a tree structure with the following main categories: individualization, innovation in clinical teaching, student participation, and nurse tutor-student nurse relationship (Table 3).

Individualization

Generally, nurses allowed students to make decisions but did not differentiate between advanced and beginner students. Students controlled their activities according to their auto-perceived ability:

‘I see autonomy as the freedom they give you for doing something. And there is no difference between first- and second-year students. They say: do this, and if they say it to you, you say to you partner: will you come with me? But they don’t discriminate…’ (St24)

‘In my ward, a job that perhaps should be for third-year students is given to us […] it gives you a lot of self-confidence. But sometimes, I think that this isn’t normal.’ (St12)

Students often call for more supervision from the tutor nurse, as this helps them to feel more secure, and involved with patient safety:

‘I think that when [the tutor nurse] asks you to do something, and you go on your own, it’s good that they give you freedom to go, and do it yourself, but it wouldn’t be bad if they accompanied you, because […] something happens, and you can’t leave the job half done, and then you have to run to ask for help, and you’re in a situation where you don’t know what to do or how to act.’ (St18)

Innovation in clinical teaching

First-year students say that everything is new when they arrive at the hospital. Unfortunately, they did not pay enough attention to previous laboratory training:

‘I think that everything is new for us, [...] I am going to be sincere, when I had skill labs, from 4 to 9 [P.M.], I arrived at the sessions, and... You don’t think it’s very important. You think that real practice placements are coming soon, and I didn’t pay attention. Well, I did pay some attention, [collective laughter]... but I wasn’t much focused, […] And soon enough I arrived here, and boy, the time I had lost! I mean, I should have been more attentive in the skills lab....’ (St1)

Regarding the explanations received from nurses, students report that any doubts are generally clarified very well:

‘Sometimes they study in the evening [consult books and other sources] to answer your question [the following day].’ (St29)

‘Yes, they take care of us. You can see which nurses care, and you go directly to them to ask your questions [several students nod].’ (St47)

‘I think that some of the ward managers are committed to teaching. Perhaps he or she doesn’t know it very well [does not have much training], but he or she tries hard. And you can feel it; he or she stays for an extra hour to teach us if necessary. And they do it with all their heart…’ (St32)

Nurses are very meticulous in their use of techniques and procedures necessary for student learning:

‘There are many nurses who put sterile gloves on because we are in the room. Sometimes they wear sterile gloves for the smallest wound! And they admit it, saying: because you are here, I am doing it properly, so you can learn...’ (St16)

Third-year students receive updated information on the use of clinical equipment:

‘They do talk about equipment. About pumps, about ventilators, about that sort of thing; they do talk. They say: this one is more modern than that one, or this one needs that piece... But this depends on the person [that is, some nurses explain the equipment while others do not].’ (St36)

Student participation

Second-year students state that they do not have full participation in some ward activities, such as the nursing shift report:

‘You don’t participate in nursing shift reports, for example. Perhaps, they [nurses] are speaking, and you make a comment. You get into their conversation. They look at you like that [the student shows an indifference glance] and they say to you: ok.’ (St18)

In contrast, there is full student involvement in other activities, such as wound treatment. Nurses even provide information for the following day’s shift:

‘[...] on wound treatment, for example, they say: when the other nurse comes tomorrow, you tell her that we have put this on him [on the patient]’ (St23)

Third-year students considered that their engagement level in ward activities depended on themselves, the characteristics of the ward and its staff, but not on the students’ level of expertise:

‘The extent to which you engage depends on yourself, on the person and your level of interest. Another factor that affects the way we engage is the tutor nurse’s working method. If you see that the nurse totally takes care of the patient, worries about all the finer details and is concerned with everything to do with the patient, you’ll do the same. However, if you’re with a tutor nurse who doesn’t work well, you aren’t going to learn much, and you aren’t going to worry so much about the details involved in the patent's care. And those details might be very important for the patient…’ (St48)

Nurse tutor-student nurse relationship

Students did not always perceive that the tutor nurse role was clearly defined. When they did, they stated the following on the relationship with the nurse:

‘To have a good relationship with a tutor, it doesn’t matter how much the tutor knows; it depends on her desire to teach... When they [nurses] do it, they are there [they get closer to the student], and we feel supported.’ (St24)

Students give their opinion about the role that the tutor nurse, a nurse that gives them individualised and continuous feedback and support in practice, should play.

‘[…] one day a nurse arrived and said: today you are going to be the nurse, and I am going to be your student’. I thought to myself: what if I do something wrong, what will happen? She said: I’m going to be with you all the time. You can ask me anything you need. In other words, she explained everything to me. All morning! The entire shift. And I learned more that day than in the whole month!’ (St31)

Based on what students say, it seems that they often feel like temporary workers whose pay is education:

‘I think that they [tutor nurse] see us as workers. You don’t come to the hospital to work, your pay is learning, your pay is training... I know they have a lot of work to do... We can help them, and they can teach us.’ (St29)

‘Students are sometimes like office boys. You often have the feeling that you’re doing the work of professionals other than nurses [such as assistant nurses], you know? […] you aren’t doing a nurse’s work. You’re not learning anything.’ (St5)

As for the age of the tutor nurse, students indicate the difference in attitude that they perceive between the “young” and “old” nurses. Above all, they emphasize their empathy with the young nurses.

‘[…] the young nurses have recently finished their studies, they put themselves in our shoes... those who studied a long time ago, the older ones, don’t count on you for certain things.’ (St11)

‘In my case, the younger ones are more considerate with me. They respect me. Just by saying: Do you want to do this? I always observe the nurse, until she gives me the opportunity to do something... They invite to you to do something; they don’t use a dictatorial tone.’ (St28)

However, young nurses have less experience and may, therefore, be at a disadvantage when clarifying certain doubts:

‘[…] I asked my tutor nurse a question... She is a young girl and admitted that she didn’t know the answer. She asked me to put the question to another nurse, one with more experience.’ (St36)

DISCUSSION

One of the aspects most frequently addressed in the literature about the clinical learning environment is how it is perceived by students. In other words, this perception corresponds to the student perspective in the process of adapting to the sociocultural scene in the clinical climate. This research gives a view about how nursing students perceive the clinical learning environment. The main topics of interest were “individualization”, “innovation in clinical teaching”, “student participation” and “nurse tutor-student nurse relationship”.

With regard to “individualization”, the students identified that there is no individualization in the clinical learning process. They do not think that aspects such as students’ experience and confidence help them to be more self-sufficient in making decisions and more autonomous in how they participate in ward activities. Nevertheless, students often call for more supervision from the tutor nurse in order to feel more secure. Usually, the tutor nurse feedback is negative, with poor communication, or what it worse, it does not exist. Constructive feedback can also help students to reflect on and to understand the theory, the practice, and their learning and socialisation experience9)(10)(29.

Feelings of anxiety or vulnerability are common in nursing students, mainly at the beginning of the clinical placement9)(10)(30)(31)(32)(33)(34)(35. This kind of stress can be related to the reality shock, the fear of making mistakes, feeling incompetent, feeling ignored, or the shame to talk with other professionals10)(31)(32. Other times, the situation is worse, and the students can feel a bullying situation31)(34)(36. Fortunately, this circumstance was not informed by our participants.

The findings of “innovation in clinical teaching” emphasized that clinical practice placements represent an adequate context where students obtain up-to-date information and training. First-year students recognized they didn’t pay enough attention to the laboratory training. As Ewertsson et al.37 explained, this training “constitutes a bridge between the university and the clinical settings.” Kaphagawani and Useh9 also described how students transferred knowledge and abilities from the classroom and simulation laboratories to the clinical context. Also, it has been suggested that longer placements in the same clinical setting and the use of different pedagogical approaches (problem-based learning, reflective learning, evidence-based learning, or e-learning) could help to solve the theory-practice gap21)(38)(39)(40)(41)(42)(43.

Students believe that “student participation” in activities depends on their experience, the characteristics of the ward, the nursing team and the tutor nurse. They recognize that they may have complete involvement in some ward tasks. Previous studies agree with these results9)(21)(33)(41. However, students argued that they had done routine activities and non-nursing duties during the clinical placement. The literature evidence that the clinical learning process will be successful if students report a variety of challenging learning opportunities which encourages them to become critical thinkers, but without increase the students' workload9)(43)(44.

Concerning “clinical supervision”, although there are a variety of nursing students supervisory models in European countries, many authors agree to consider the tutor nurse as the key role in the process of clinical supervision9)(21)(41)(42)(44)(45. In addition, the student-nurse tutor relationship seems to be decisive for the students’ learning, both epistemologically and ontologically43. However, in this study, the majority of the students do not feel that the tutor nurse role was clearly defined. The nurses’ shifts and the students’ work schedule are noted as one of the most important causes for our participants. In that sense, the role of the tutor nurse should be clarified, enriched, and upgraded internationally16)(42)(43.

Based on our students’ comments, it seems that they often feel like temporary workers who are paid in learning. Melia46 explained this feeling regarding mistaken student identity, as in “Am I a student or a worker?” Other authors have suggested that nursing students are sometimes treated as members of the nursing team in clinical areas, even though that is not their position47)(48. Sometimes students felt that their primary purpose on placement was to support staff rather than develop their skills and enhance their learning.48)

Finally, students reported feeling more empathy with young than with older tutors. In this sense, Houghton10 found that approachability, confidence, and motivation are characteristics of good tutors, which could be in line with our findings.

Limitations of the study

We are aware that the results of this study are limited to the students’ perspective of this purposive sample. Including the perceptions of nurses, nurse tutors, teachers, and patients of the clinical learning environment would be possible with further research, along with a cross-cultural and international perspective.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that: 1) no individualization is involved in the clinical learning process; 2) student participation in ward activities depends on the student`s experience, the characteristics of the ward, the nursing team and nurse tutor; 3) students feel that the role of the nurse tutor is not clearly defined; 4) anxiety, vulnerability and feelings of being “temporary workers” are common in nursing students.

These results should prompt reflection on these aspects of the supervisory process. Clinical learning is one of the most important of all students' experiences while on placement, given that it is during this period of training when they put the knowledge, skills and attitudes required for their future working life into practice.

REFERENCIAS

1. Galbraith MW. Attributes and Skills of an Adult Educator. In: Galbraith MW, editors. Adult Learning Methods. Robert E. Malabar: Krieger Publishing Company; 1990. [ Links ]

2. Hiemstra R, Sisco B. Individualizing Instruction: Making Learning Personal, Empowering and Successful. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1990. [ Links ]

3. Pappas JP. Environmental Psychology of the Learning Sanctuary. In: Simpson, EG, Kasworm CE, editors. Revitalizing the Residential Conference Centre Environment. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1990. [ Links ]

4. Fraser BJ. Science Learning Environments: Assessment, Effects and Determinants. In: Fraser BJ, Tobin KG, editors. International Handbook of Science Education. London: Klumer Academic Publishers; 1998. p. 527-564. [ Links ]

5. Hiemstra R. Creating Environments For Effective Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc; 1991 [ Links ]

6. Knowles M. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. 4nd ed. Houston Gulf Publishing; 1990. [ Links ]

7. Cleveland B, Fisher K. The evaluation of physical learning environments: A critical review of the literature. Learning Environment Research; 2014;17:1-28. doi:10.1007/s10984-013-9149-3. [ Links ]

8. Roxburgh M., Watson R., Holland K., Johnson M., Lauder W, Topping K. A review of curriculum evaluation in United Kingdom nursing education. Nurse Educ Today; 2008;28(7):881-889. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2008.03.003. [ Links ]

9. Kaphagawani NC, Useh U. Analysis of Nursing Students Learning Experiences in Clinical Practice: Literature Review. Studies on Ethno-Medicine; 2013;7(3): 181-185. [ Links ]

10. Houghton CE. "Newcomer adaptation": a lens through which to understand how nursing students fit in with the real world of practice; J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(15-16):2367-2375. doi.10.1111/jocn.12451. [ Links ]

11. The European Higher Education Area. Declaration Bologna. Joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education; 1999 [ Links ]

12. Zabalegui A, Cabrera E. New nursing education structure in Spain. Nurse Educ Today; 2009;29(5):500-504. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2008.11.008. [ Links ]

13. Dunn SV, Hansford B. Undergraduate nursing students' perception of their clinical learning environment. J Adv Nurs; 1997;25(6):1299-1306. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251299.x. [ Links ]

14. Chan DSK. Assessing nursing students' perceptions of hospital learning environment. [PhD-thesis]. Shatin: University of Hong Kong; 1999. [ Links ]

15. Thorell-Ekstrand I, Bjorvell H. Nursing Students' experience of care planning activities in clinical education. Nurse Educ Today; 1995;15(3):196-203. doi:10.1016/S0260-6917(95)80106-5. [ Links ]

16. Flott EA, Linden L. The clinical learning environment in nursing education: a concept analysis; J Adv Nurs; 2016;72(3):501-513. doi:10.1111/jan.12861. [ Links ]

17. Lee CH, French P. Education in the practicum: a study of the ward learning climate in Hong Kong; J Adv Nurs; 1997;26(3):445-462. [ Links ]

18. Saarikoski M. Clinical Learning Environment and Supervision. Development and validation of the CLES evaluation scale. [PhD-thesis] Turku: University of Turku; 2002 [ Links ]

19. Suhonen R, Saarikoski M, Leino-Kilpi H. Cross-cultural research: a discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud; 2009;45:(6):204-212. [ Links ]

20. Koskinen L, Taylor-Kelly H, Bergknut E, Lundberg P, Muir N. Olt H, Richardson E, Sairanen R, De Vlieger L. European Higher Health Care Education Curriculum: Development of a Cultural Framework. J Transcult Nurs; 2012;23(3):313-319. doi:10.1177/1043659612441020. [ Links ]

21. Saarikoski M, Ekaterini PK, Pérez R, Tichelaar E, Tomietto M, Warne T. Students' experiences of cooperation with nurse teacher during their clinical placements: An empirical study in a Western European context. Nurse Educ Pract; 2013;13(2):78-82. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2012.07.013. [ Links ]

22. Kajander-Unkuri S, Salminen L, Saarikoski M, Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H. Competence areas of nursing students in Europe. Nurse Educ Today; 2013;33(6):625-632. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.01.017. [ Links ]

23. Espitia E. La fenomenología interpretativa como alternativa apropiada para estudiar los fenómenos humanos. Investigación y educación en enfermería; 2013 18(1), 27-35 [ Links ]

24. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care; 2007;19(6):349-357. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [ Links ]

25. Vizcaya Moreno MF, Perez Cañaveras RM, De Juan Herrero J. El clima social: valoración del entorno de aprendizaje clínico desde la perspectiva de los estudiantes de enfermería. In: CIDE, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Secretaría General de Educación editors. Premios Nacionales de Investigación Educativa 2004; 2005:291-310. [ Links ]

26. Vizcaya Moreno MF. Valoración del entorno de aprendizaje clínico hospitalario desde la perspectiva de los estudiantes de enfermería. [PhD-thesis] Alicante: University of Alicante; 2005. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/13280 [ Links ]

27. Cormark DFS. The Research Process in Nursing. 3nd ed. London Blackwell Science; 1996 [ Links ]

28. Burnard P. A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Educ Today; 1991;11(6):461-466. doi:10.1016/0260-6917(91)90009-Y. [ Links ]

29. Saarikoski M, Warne T, Kaila P, Leino-Kipi H. The role of the nurse teacher in clinical practice: an empirical study of Finnish student nurse experiences. Nurse Educ Today; 2009;29(6):595-600. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2009.01.005. [ Links ]

30. Henderson A, Twentyman M, Heel A, Lloyd B. Students' perception of the psycho-social clinical learning environment: an evaluation of placement models. Nurse Educ Today; 2006;26(7):564-571. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2006.01.012. [ Links ]

31. Hoel H, Giga SI, Davidson MJ. Expectations and realities of student nurses' experiences of negative behaviour and bullying in clinical placement and the influences of socialization processes. Health Services Management Research; 2007;20(4):270-278. [ Links ]

32. Pearcey P, Draper P. Exploring clinical nursing experiences: listening to student nurses. Nurse Educ Today; 2008;28(5):595-601. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2007.09.007. [ Links ]

33. Chuan OL, Barnett T. Students, tutor and staff nurse perceptions of the clinical learning environment. Nurse Educ in Practice; 2012;12(4):192-197. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2012.01.003. [ Links ]

34. Seibel M. For us or against us?. Perceptions of faculty bullying of students during undergraduate nursing education clinical experiences. Nurse Educ Pract; 2014;14(3):271-274. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.013. [ Links ]

35. Sun FK, Long A, Tseng YS; Huang HM, You JH; Chiang CY. Undergraduate student nurses' lived experiences of anxiety during their first clinical practicum: A phenomenological study; Nurse Educ Today; 2016;37:21-26. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2015.11.001. [ Links ]

36. Clarke CM, Kane DJ, Rajacich DL; Lafreniere KD. Bullying in undergraduate clinical nursing education. Journal of Nurse Education; 2012;51(5):269-76. doi:10.3928/01484834-20120409-01. [ Links ]

37. Ewertsson M, Allvin R, Holmström IK, Blomberg K. Walking the bridge: Nursing students' learning in clinical skill. Nurse Educ in Pract; 2015;15(4):277-283. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2015.03.006. [ Links ]

38. Sharif F, Masoumi S. A qualitative study of nursing student experiences of clinical practice; BMC Nurs; 2005;4,6. doi:10.1186/1472-6955-4-6. [ Links ]

39. Ehrenberg AC, Haggblom M. Problem-based learning in clinical nursing education: Integrating theory and practice. Nurse Educ in Pract; 2007;7(2):491-498. [ Links ]

40. McKenna L, Wray N, McCall L. Exploring continuous clinical placement for undergraduate students; Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract; 2009;14(3): 327-335. doi:10.1007/s10459-008-9116-4. [ Links ]

41. Warne T, Johansson UB, Papastavrou E, Tichelaar E, Tomietto M, Bossche KVD, Vizcaya Moreno MF, Saarikoski M. An exploration of the clinical learning experience of nursing students in nine European countries. Nurse Educn Today; 2010;30(8):809-815. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.03.003. [ Links ]

42. Dimitriadou M, Papastavrou E, Efstathiou G; Theodorou M. Baccalaureate nursing students' perceptionns of learning and supervision in the clinical environment. Nurs Health Sci; 2015;17:236-242. doi:10.1111/nhs.12174. [ Links ]

43. Sandvik AH, Eriksson K, Hili Y. Understanding and becoming-the heart of the matter in nurse education. Scand J Caring Sci; 2015;29: 62-72. doi: 10.1111/scs.12128 [ Links ]

44. Paton B. The Professional Practice Knowledge of Nurse Preceptors. J Nurs Educ; 2010;49(3):143-149. doi:10.3928/01484834-20091118-02. [ Links ]

45. Koontz AM, Mallory JL, Burns JL, Chapman S. Staff nurses and students: the good, the bad and the ugly. MEDSURG Nursing 2010;19(4):240-246. [ Links ]

46. Melia K. Learning and Working: The Occupational Socialisation of Nurses. London: Tavistock, 1987 [ Links ]

47. Ashworth P, Morrison P Some ambiguities of the students' role in undergraduation nurse training. J Adv Nurs 1989;14(12):1009-1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb01511.x. [ Links ]

48. Hamshire C, Willgoss TG, Wibberley C. The placement was probably the tipping point' -The narratives of recently discontinued students. Nurse Educ Pract; 2012;12(4):182-186. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2011.11.004. [ Links ]

Received: November 25, 2016; Accepted: April 22, 2017

texto em

texto em