Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.20 no.62 Murcia Abr. 2021 Epub 18-Maio-2021

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.426881

Reviews

Circadian dyssynchrony and its effect on metabolic syndrome parameters in workers: An integrative literature review

1Nursing Department, Division of Biological and Health Sciences of the Universidad de Sonora. Mexico

Introduction:

The loss of the circadian rhythm caused by sleep disorders is considered an important risk factor for developing metabolic diseases such as hyperglycemia and insulin resistance.

Objective:

Analyze the existing information regarding studies on circadian dyssynchrony in workers and its influence on metabolic syndrome of anthropometric parameters.

Method:

A search was carried out in electronic databases such as EBSCO, Thompson Reuters, PubMed, and Scopus; the selected search terms were shift work, melatonin, cortisol, metabolic syndrome, night shift, and circadian rhythm in Spanish and English published from January 2015 to December 2018. The extraction was carried out using a predesigned form.

Results:

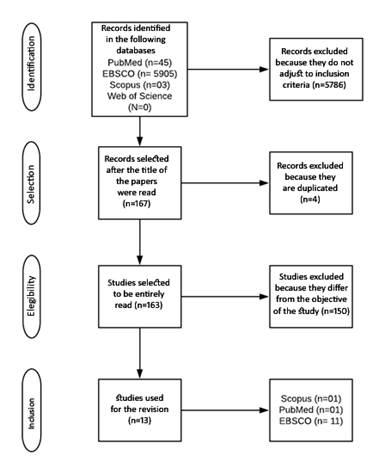

The search in the databases yielded 5,953 papers; after the investigation and depuration of the aforementioned papers applying the eligibility criteria, 13 papers were obtained which were organized in two dimensions for their analysis, these were called a) shift work and metabolic risk factors, and b) shift work and the circadian cycle.

Conclusions:

The relationship between night work or rotating shift with various metabolic disorders is consistent.

Key words: Metabolic Syndrome; Circadian Rhythm; Shift Work Schedule; Melatonin; Cortisol

INTRODUCTION

According to the Health Metrics and Assessment Institute, the main causes of death in Mexican people are cardiovascular illnesses, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney illness, therefore, these illnesses are considered as a national public health problem1. There are several forms of calling these illnesses, one of them is the metabolic syndrome, which according to the International Diabetes Federation is comprised by several interrelated metabolic indicators such as hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, increase in abdominal girth and triglycerides, and reduction in HDL cholesterol. The diagnosis of this syndrome is used as risk predictor for cardiometabolic diseases2.

In the human body there are physiological functions that repeat themselves with determined regularity and time, in relation with the day, night, and seasons cycles, which are known as biological rhytms3. These rhythms are controlled by internal biological clocks which are located in the central nervous system4, which generate a biological balance when they synchronize with external clocks known as zeitgebers, which are in charge of coordinating the activity of the nervous system with the environment4, all of which regulated by the light signals that travel through cells that are sensitive to the light of the retina toward the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus, making that people respond in this way to the day/night cycle5.

The circadian cycle is a biological rhythm that regulates the functions of the body through the secretion of hormones, within a system of 24 hours of duration, which influences the sleep and awake cycles, body temperature, blood pressure, release of endocrine hormones, and metabolic activity6. In the last decade, several studies have been carried out that relate the lost of synchrony of the circadian cycle as an important risk factor to develop metabolic illnesses such as hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and obesity, among others7.

Health and wellbeing are affected by several aspects, such as daily routine, life style, metabolism, and genetic factors8. Nowadays, work schedules, mainly night or rotating shifts, request employees to carry out activities in schedules that put out of synchrony the functions of the circadian rhythm, due to the modification of food intake schedule, sleep patterns, and social activities, all of this regulated by exogenous factors9. These changes in daily sleep and awake schemes generate hormonal alterations that affect the health of those who experience these alterations, increasing the risk to have breast cancer, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome. The objective of this research is to analyze the existing literature regarding scientific research with respect to circadian dyssynchrony and its effects on parameters of the metabolic syndrome in workers.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

This research is an integrative revision of literature, which in order to facilitate the exploration of scientific information a search strategy to put together all evidence possible to respond to a specific research question was formed11, that is, which is the scientific information available in relation to the circadian dyssynchrony and its effect on the metabolic syndrome parameters in workers? Eligibility criteria were the following: Papers whose population included were men or women, of legal age, workers of night, rotating, and/or day shifts, with no restrictions on study design or type of intervention used. Papers in Spanish and English published between January 01, 2015 and December 31, 2018 were included, and only papers available in full text were selected. This search took place in September 2019.

The search for papers took place in the electronic databases EBSCO, Thompson Reuters Web of science, PubMed, and Scopus. The U.S. National Library of Medicine MeSH vocabulary descriptors used were “shift work”, “melatonin”, “cortisol”, “metabolic syndrome”, “night shift”, and “circadian disrupt”. When necessary, the search terms were modified to be adapted to the features of the different databases. The electronic search strategy formed for the evaluation of the relationship of metabolic syndrome and circadian dyssynchrony was as follows: (“Circadian rhythm disorder” OR “Chronobiology Disorders” OR “Circadian Dysregulation”) AND (“Metabolic syndrome” OR “Dysmetabolic Syndrome X”) AND (“Shift work” OR “Night Shift Work” OR “Rotating Shift Work”) AND (“Melatonin”) AND (“Cortisol”).

The selection of papers was carried out independently by two reviewers and, in case of disagreement, the support of a third reviewer was secured. The studies were selected by means of a detailed review and evaluation of the title and abstract of each paper in order to assess their relevance regarding the objective of the review; otherwise, the paper was excluded and, if the reviewer considered that more information was needed to evaluate a given paper, the complete document was consulted. The extraction was performed using an extraction form of our own design, in which the following criteria were evaluated: Objective, method/sample, results and conclusion. The search was performed considering the following variables: Work shift, fasting glucose, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, abdominal girth, blood pressure, cortisol, and melatonin. The Cochrane Collaboration tool was used independently in the papers to assess the risk of bias (risk of selection, realization, loss and detection) and validity of the papers considering randomization, double-blind status, and description of losses during follow-up as main guidelines.

RESULTS

Search in the databases yielded 5,953 papers. After the search and filtering of these papers, applying the eligibility criteria, 13 papers were selected as the object of the analysis. See Figure 1. The main causes of exclusion were date of publication and full text. Some papers evaluated only the circadian cycle, but not its implications in the human metabolism.

In terms of country of origin, 15.4% of the papers came from Brazil, 15.4% from Canada, 15.4% from China, 7.7% from the United States of America, 7.7% from Jordan, 7.7% from Germany, 7.7% from Greece, 7.7% from Poland, and 7.7% from Denmark. 53.8% of the papers were published in 2015, 30.8% in 2018, and 15.4% in 2017. All the papers were in English.

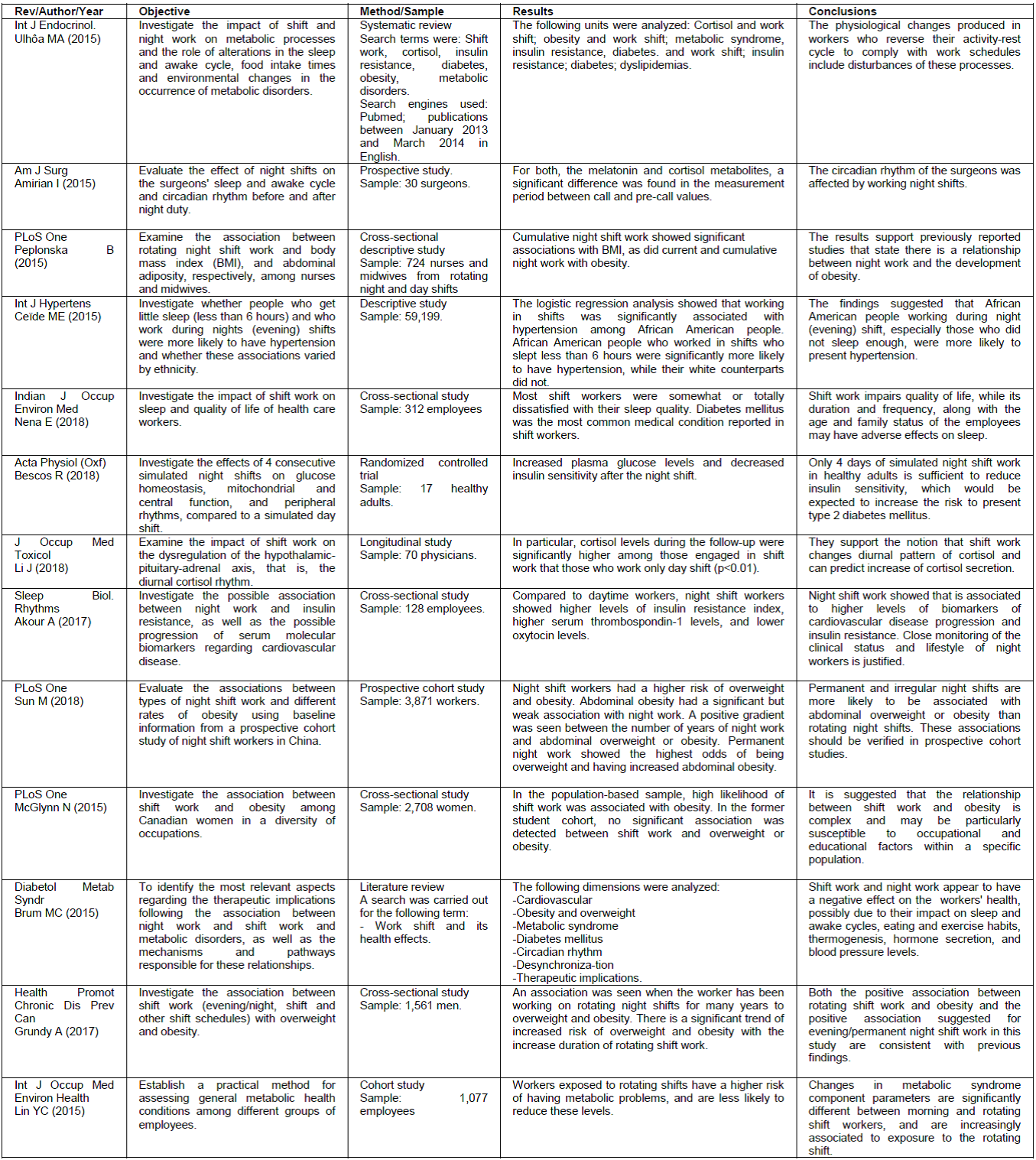

Table 1 shows a summary of the 13 papers selected for this systematic review, which met the stipulated eligibility criteria.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, there has been an increase in research aimed at finding out the possible relationship between shift work and its implications on metabolism. Next, the different results found in this research are analyzed by grouping the papers in two dimensions: a) shift work and metabolic syndrome and b) shift work and circadian cycle.

Dimension a) Shift work and metabolic risk factors. The main result of this literature review is a consistent association between night or rotating shift work and various metabolic alterations. In two of the studies examined, a review of the literature was carried out, both of which agree that changes or alterations in the sleep and awake cycle disrupt the metabolic processes of workers12,13. The changes can manifest themselves as cardiovascular diseases, weight gain, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and diabetes, which become an occupational risk and could lead to temporary or permanent work disability, generating loss of income and productivity for the individual, as well as high costs to the country's health budget14.

Most studies attempt to establish a relationship between a work shift and one or more of the components of the metabolic syndrome15, mainly obesity and overweight16,19. In all cases there is a significant difference between the day shift and the night or rotating shift in which it is observed that it is more likely to suffer from overweight or obesity if working at night, and night workers have greater difficulty in overcoming the disease. The second most observed result is an increase in fasting plasma glucose levels and insulin resistance20)(21)(22, which increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus in workers23. Consequently, several studies have made proposals to counteract the adverse effects of night work, proposing scheduled naps, extra remuneration for the risk and limitations for pregnant and breastfeeding women24.

Dimension b) Shift work and circadian cycle. A small percentage of the selected studies seek to find an association between work shift and changes in cortisol and melatonin parameters, as well as the sleep/wake cycle25,26. The result of a change in the diurnal pattern of melatonin and cortisol in participants who work night or rotating shifts is persistent, which is characterized by an increase in cortisol secretion which in turn is related to multiple metabolic alterations such as hypertension27 and overweight28, this, along with stress and depression, which according to studies is shown as health risk factors in night workers29.

However, studies suggest that these results may be affected by various factors such as age, sex, race, unhealthy habits, genetics, and social and family life, among others30.

CONCLUSIONS

This research will help to interpret that there is evidence that associates circadian cycle disturbances with metabolic risk factors in night and rotating shift workers, and that this can lead to the development of metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, and other pathologies by these workers. Studies point to an association of circadian dyssynchrony not only to metabolic disorders, but also to psychological, social, and genetic disorders.

Although night and rotating shifts are necessary for the proper functioning of today's society, accessible and feasible alternatives must be proposed in order to limit the damage caused to the health of the workers, and, thus, contribute to the reduction of morbidity and mortality among them.

REFERENCIAS

1. Lozano R, Gómez H, Garrido F, Jiménez A, Campuzano JC, Franco F, et al. La carga de enfermedad, lesiones, factores de riesgo y desafíos para el sistema de salud en México. Salud Pública Mex. 2013; 55(6):580-94. [ Links ]

2. González A, Luis S, Elizondo S, Zúñiga JS. Prevalencia del síndrome metabólico entre adultos mexicanos no diabéticos, usando las definiciones de la OMS, NCEP-ATPIIIa e IDF. Rev Med Hosp Gen (Mex). 2008; 71(1):11-9. [ Links ]

3. Saderi N, Escobar C, Salgado-Delgado R. La alteración de los ritmos biológicos causa enfermedades metabólicas y obesidad. Rev Neurol. 2013; 57(2):71-8. [ Links ]

4. Castellanos M, Rojas A, Escobar C. De la frecuencia cardiaca al infarto. Cronobiología del sistema cardiovascular. Rev Fac Med UNAM. 2009; 52(3):117-21. [ Links ]

5. García G, Sánchez I, Martínez G, Llanes A. Cronobiología: Correlatos básicos y médicos. Rev Med Hosp Gen Méx. 2011; 74(2):108-14. [ Links ]

6. León R. Sueño, ciclos circadianos y obesidad. Arch en Med Fam. 2018; 20(3):139-143. [ Links ]

7. Delgado S, Pardo F, Briones E. La desincronización interna como promotora de enfermedad y problemas de conducta. Salud Ment. 2009; 32(1):69-76. [ Links ]

8. Álvarez L. Los determinantes sociales de la salud: más allá de los factores de riesgo. Rev Gerenc. Polit. Salud [Internet]. 2009 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 8(17):69-79. Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/545/54514009005.pdf [ Links ]

9. Van Laake W, Luscher F, Young E. The circadian clock in cardiovascular regulation and disease: lessons from the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine 2017. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39: 2326-9. [ Links ]

10. Escobar C, González E, Velasco M, Angeles M. Poor quality sleep is a contributing factor to obesity. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment J Eat Disord [Internet]. 2013 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 4(2):133-42. Disponible en: http://journals.iztacala.unam.mx/index.php/amta/article/view/279 [ Links ]

11. Urrútia G, Bonfill X. PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med Clin (Barc). 2010; 135(11):507-11. [ Links ]

12. Ulhôa A, Marqueze C, Burgos A, Moreno C. Shift work and endocrine disorders. Int J Endocrinol [Internet]. 2015 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 2015: 826249. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/826249 [ Links ]

13. Brum B, Filho D, Schnorr C, Bottega B, Rodrigues C. Shift work and its association with metabolic disorders. Diabetol Metab Syndr [Internet]. 2015 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 7(1):1-7. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-015-0041-4 [ Links ]

14. Romero M, Álvarez J, Prieto A. Calidad de sueño en trabajadores a turnos-nocturnos y su relación con la incapacidad temporal y siniestralidad laboral. Un estudio longitudinal. Rev Enfermería del Trab. 2016; 6(1):19-27. [ Links ]

15. Lin Y, Hsieh I, Chen P. Utilizing the metabolic syndrome component count in workers' health surveillance: An example of day-time vs. day-night rotating shift workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2015; 28(4):675-88. [ Links ]

16. Sun M, Feng W, Wang F, Zhang L, Wu Z, Li J, et al. Night shift work exposure profile and obesity: Baseline results from a Chinese night shift worker cohort. PLoS One. 2018; 13(5):1-14. [ Links ]

17. Peplonska B, Bukowska A, Sobala W. Association of rotating night shift work with BMI and abdominal obesity among nurses and midwives. PLoS One. 2015; 10(7):1-13. [ Links ]

18. Grundy A, Cotterchio M, Kirsh VA, Nadalin V, Lightfoot N, Kreiger N. Rotating shift work associated with obesity in men from Northeastern Ontario. Heal Promot Chronic Dis Prev Canada. 2017; 37(8):238-47. [ Links ]

19. McGlynn N, Kirsh VA, Cotterchio M, Harris MA, Nadalin V, Kreiger N. Shift Work and Obesity among Canadian Women: A Cross-Sectional Study Using a Novel Exposure Assessment Tool. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2015 [citado 20 nov 2019] 10(9): e0137561. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137561 [ Links ]

20. Nena E, Katsaouni M, Steiropoulos P, Theodorou E, Constantinidis TC, Tripsianis G. Effect of Shift Work on Sleep, Health, and Quality of Life of Health-care Workers. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2018; 22(1):29-34. [ Links ]

21. Akour A, Abu R, Alefishat E, Kasabri V, Bulatova N, Naffa R. Insulin resistance and levels of cardiovascular biomarkers in night-shift workers. Sleep Biol. Rhytms [Internet]. 2017 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 15: 283-290. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-017-0109-7 [ Links ]

22. Bescos R, Boden MJ, Jackson ML, Trewin AJ, Marin EC, Levinger I, et al. Four days of simulated shift work reduces insulin sensitivity in humans. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2018; 223(2). [ Links ]

23. Sánchez B, Chico G, Rodríguez A, Sámano R, Veruete D, Morales R. Detección de riesgo de diabetes tipo 2 y su relación con las alteraciones metabólicas en enfermeras. Rev. Latino-Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2019 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 27:e3161. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.3002.3161 [ Links ]

24. De Castro T, Rotenberg L, Golher R, Silva A, Paiva E, Härter R. Siesta durante la guardia nocturna y la recuperación tras el trabajo entre enfermeros de hospitales. Rev. Latino-Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2015 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 23 (1):114-21. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.0147.2532 [ Links ]

25. Amirian I, Andersen LT, Rosenberg J, Gögenur I. Working night shifts affects surgeons biological rhythm. Am. J. Surg [Internet]. 2015 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 210(2): 389-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.09.035 [ Links ]

26. Li J, Bidlingmaier M, Petru R, Gil FP, Loerbroks A, Angerer P. Impact of shift work on the diurnal cortisol rhythm : a one-year longitudinal study in junior physicians. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2018; 1-9. [ Links ]

27. Ceide M, Pandey A, Ravenell J, Donat M, Ogedegbe G, Jean-Louis G. Associations of Short Sleep and Shift Work Status with Hypertension among Black and White Americans. Int J Hypertens [Internet]. 2015 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 2015:697275. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/697275 [ Links ]

28. Rosa D, Terzoni A, Dellafiore A, Destrebecq A. Systematic review of shift work and nurses health. Occupational Medicine [Internet]. 2019 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 69(4): 237-243. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqz063 [ Links ]

29. Cremades J, Maciá L, López MJ, Pedraz A, González M. Una nueva aportación de clasificar factores estresantes que afectan a los profesionales de enfermería. Rev. Latino-Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2017 [citado 20 nov 2019]; 25:e2895. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1240.2895 [ Links ]

30. Díaz E, López R, González M. Hábitos de alimentación y actividad física según la turnicidad de los trabajadores de un hospital. Enferm Clin. 2010; 20(4):229-35. [ Links ]

Received: May 05, 2020; Accepted: July 24, 2020

texto em

texto em