Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.20 no.64 Murcia oct. 2021 Epub 25-Oct-2021

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.479441

Originals

Patient perception of nursing care in the context of the COVID-19 crisis

1 Centro de Salud José Aguado, León, España.

2 Hospital Marina Salud de Dénia, Dénia, España. macrina-96@hotmail.com

3 Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Departamento de Enfermería y Fisioterapia Universidad de León, León, España.

4 Enfermera de Calidad y Formación. Hospital Universitario de León, León, España.

5 Hospital Universitario de León, León, España.

Background:

The COVID-19 pandemic has heavily altered regular procedures of healthcare systems worldwide. Daily work has become physically and emotionally exhausting for health care professionals, forced to face and adapt to new challenges and stressful situations. This situation weighs on the daily nursing practice and might have an impact on the quality of care provided and on the level of satisfaction perceived by hospitalized patients. Thus, the present study aimed to determine the patient’s perception of humanized nursing care received during their hospital stay.

Methods:

A descriptive, quantitative, cross-sectional study was carried out, in which telephone interviews were conducted in 357 people >18 years of age who were admitted for more than 24 hours to the Hospital de León in order to asses patient´s perception. One instrument used was The Perception of Behaviors of Humanized Nursing Care Scale (PCHE), to evaluate in three dimensions (D): qualities of nursing practice (D1), openness to nurse-patient communication (D2), and willingness to care (D3). In addition, an institutional satisfaction survey was performed to know the opinion on the quality of customer service in hospitalization area.

Results:

The percentage of patients scoring as “always” every dimension was: D1 = 91.2%; D2= 81.4%; and D3= 87.8%. Patient satisfaction obtained a mean score of 4.6 out of 5. 42.3% of population were men and 57.7% were women, most in the age range 61-75 years. The predominant marital status and educational level were married and basic-medium, respectively.

Conclusion:

Despite the negative impact of COVID-19 in the health care system, patients perceived humanized nursing care received as very successful.

Key words: humanized care; nursing staff hospital; patient satisfaction; quality of health

INTRODUCTION

Nursing is a science and profession based on the art of caring. Its fundamental pillar is the biopsychosocial and spiritual care of people, attending to their basic needs in the most vulnerable moments1,2). Nursing is based on care and the provision of health services, with a commitment to and responsibility for the delivery of care unique to this science1.

The theory of humanized care according to Jean Watson places special importance on human dignity and incorporates concepts such as humanization of care, value-taking, cultivation of sensitivity, and relationship of help between individuals3. She also mentions the ability of nursing professionals to show concern for people in all states of being, to facilitate healing or coping with disease, and to achieve inner harmony. These abilities are increased with the theory because it guides professional practice and successful results. Nurses can quickly organize patient data, decide which nursing action is the most necessary, and deliver care with an expectation of outcomes3.

However, as the health requirements of the population have changed, the scope of nursing practice, theory, and abilities must also change. Nurses must take on complex new roles. What is truly needed in this changing world is to ensure structured, ongoing professional development for nurses that is focused on humanized nursing care4. Formalizing a model of humanization of care with a global perspective would be useful to evaluate nursing interventions in a consistent manner and improve results5.

Humanized care is needed not only by patients and their significant others, but also by nurses. On the one hand, nurses today are required to be highly trained in terms of proper education and critical thinking, with a caring human heart. On the other hand, it is necessary for patients and family members to learn how to communicate gratitude for the care they receive, because this becomes another way of caring for nurses6. The findings revealed the six noble qualities of love, commitment, empathy and sympathy, compassion, confidence and competence, and confidentiality and privacy that nurses can use to communicate in their daily practice to provide effective humanized care to individuals, families, and groups. These factors have a return link effect on the perception of patients and nurses, which determines the quality of nursing communication and care delivery2.

Communication failures are associated with serious consequences for patients and healthcare teams, including nurses. Nurses need to communicate and express professional concerns and share common critical language. Effective communication can bring hope to patients and build proper professional relationships for high-quality nursing care5.

It has been shown that gaps still exist between the expectation of humanization by people involved in the process of care and what actually happens in clinical practice5. Also, effective nursing communication can bring hope to patients and build proper professional relationships for high-quality nursing care5. Some authors suggest that it is difficult to maintain humanitarian values in the act of care in public health institutions, where they seem to become invisible in biomedical work, but nurses should keep communicating and supporting patients7. Leininger McFarland explains: "The attitudes and practice of care is all that highlight the contribution of nurses from other disciplines”8.

Over time, human needs have changed, and so has nursing care. In recent decades, the use of technology has increased, and nursing care has become more specific and improved in quality9, but this has not been the only factor that has changed nursing care.

In practice, nursing professionals comply with standards and procedures, but norms, or better, nursing protocols, have not yet been developed that indicate how we should act in sensitive care or humanized care. Currently, the importance of defining lines of action that lead to the construction of a National Policy of Humanized Attention in two directions is identified: towards the patient and towards nurses, so that in this harmony true environments sensitive to reality are generated of the other10.

Actually, nurses face a new challenge in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, as it has effects on the fear of becoming infected and infecting others and the difficulty of managing patients' conditions and relationships in this stressful situation. Intensive work in this context exhausts nurses physically and emotionally, but they continue to show the spirit of dedication and feel a great responsibility with patients to overcome the pandemic, with resilience and a spirit of professional commitment to overcome difficulties7,8. The implication is that humanized work has a favorable impact on physical and psychological health, resulting in better job satisfaction, less illness, and positive contributions to health and well-being11).

There is a validated instrument which tries to define these lines of action and somehow quantitatively measure humanized care. It is determined that The Perception of Behaviors of Humanized Nursing Care Scale (PCHE), adapted by González-Hernández12, is valid and reliable for its application in the hospital setting, and is available to the scientific community at a national and international level. It is important that nursing professionals make use of this type of instruments that allow a space for the professionals to reflect on their discipline and that patients are given a moment of feedback regarding care, which contributes to mutual growth.

Because of these findings, the present work proposes the hypothesis that patients at University Hospital of León receive humanized nursing care despite the context of the crisis during their stay, therefore their level of satisfaction is also high. Also, the humanized care perceived by patients admitted to this hospital may be directly related to their sociodemographic data and health conditions including age, marital status, and level of education.

Because the context of the health crisis is recent, studies should show whether or not the pandemic could affect humanized patient care, and the perceived level of satisfaction. Humanized nursing care has always been a holistic part of the nursing profession, and it is perceived by patients and nurses as a driving dynamic toward recovery and career progression6.

Nurses face new challenges in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, with intensive work and stressful situations. It makes nurses suffer from physical and psychological exhaustion, and as a consequence patient care and satisfaction may be affected.

Primary aim

Determine the patient’s perception of humanized nursing care received during their stay at the University Hospital of León

Secondary aims

Determine the perception of humanized care by hospitalized patients behavior in the three categories covered by the instrument used.

Identify the level of satisfaction perceived by patients during the period of hospitalization.

Establish a relationship between perception of humanized care and satisfaction with sociodemographic variables.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a descriptive, quantitative, and cross-sectional study in which telephone interviews were conducted with the study population. A bibliographic search of primary and secondary sources was carried out previously.

The study population was randomly selected from 2546 patients, who were all of patients admitted to the University Hospital of León since 14 of September to 18 October 2020. In order to carry out this study, we obtained prior authorization from the Ethics and Research Committee of León and El Bierzo, and subsequently the admission service of the hospital. Finally, 357 patients were included in the study (n = 357) who met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria

- Patients ≥18 years old admitted to different hospital units.

- Admissions of more than 24 hours’ duration.

- Patients discharged between 14 September and 18 October 2020.

- Patients who gave oral consent to participate in this research.

Exclusion criteria

- Patients with any pathology causing unconsciousness, neurological damage, or cognitive impairment.

- Patients admitted to psychiatric units.

- Patients with speech impediments.

- Patients who died during the time between discharge and telephone interview.

The sample obtained was estimated probabilistically with a confidence interval of 95% and an error of 5%.

The surveys were carried out in the months of December 2020 and January 2021.

Information collection technique and tools

For data collection, 3 instruments were used. First, a questionnaire with sociodemographic and clinical data was used, along with a scale called Perception of Behaviors of Humanized Nursing Care (PCHE), 3rd version, validated by exploratory factor analysis by González in 201512 and an institutional satisfaction survey, Opinion on the Quality of Customer Service Hospitalization Area of CAULE.

The PCHE 3rd version consists of a 32-item questionnaire with a 4- point Likert scale with values assigned to questions as follows: never = 1 point, sometimes = 2 points, almost always = 3 points, and always = 4 points. It has a maximum score of 168 points and a minimum of 42.

In addition, the 3rd version has content validity, having a content validity index of 0.98 per experts, and construct validity through the measurement of an exploratory factor analysis that generated three categories or dimensions called: qualities of the nursing, openness to nurse-patient communication and willingness to care, which measure the construct of the instrument Humanized care behaviors. Finally, it was determined that the PCHE instrument to its new version, is reliable, as obtained Cronbach's alpha of 0.9612

The institutional satisfaction survey assesses opinions about the quality of customer service through 11 items with a 5-point Likert scale, scoring from 1 = very bad to 5 = very good. The overall level of satisfaction (item 12) was also included, with a 4-point Likert scale: 1 = not at all satisfied, 2 = a little satisfied, 3 = satisfied, and 4 = very satisfied.

Sociodemographic data were also collected, including age, gender, marital status, and educational level.

The technique used was telephone calls between November and December 2020, in which the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation was defined and the consent of the participants was explicitly requested. The study authors collected data from participants who met the inclusion criteria and completed all items by telephone with prior informed consent. After this, participants were coded with numbers, so as to respect anonymity and confidentiality of the data.

Data processing and analysis

A data matrix was created in Microsoft Excel and the data were subsequently analyzed with the Epi InfoTM program and SPSS Statistics 26.0. The results were presented in statistical Tables for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used in the form of frequency Tables, measures of central tendency, contingency Tables, and significance analysis.

Ethical considerations

This project was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of León and El Bierzo Area with internal registration number 20172 and respected the ethical principles supported by the Belmont Report and the Declaration of Helsinki, and the right to confidentiality is guaranteed. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic variables

The profile of surveyed participants (n = 357) is characterized by a mean age of 61.3 years, with a median of 64.2 years, a maximum of 93.6 years, and a minimum of 18.2 years. The ages are distributed in four ranges (Table 1); the most represented range was 61 to 75 years (31%), followed by 46 to 60 years (25%), >75 years (21%), 31 to 45 years (19%), and 18 to 30 years (4%).

In the sample, 42.3% were men and 57.7% were women. The distribution of marital status by gender is shown in Table 1; married status stands out above the others, with almost half of those surveyed (58.82%), and with homogeneous results between genders. The widowed range is the opposite, with scarce representation (15.97%) and differences between genders: 14.04% men and 85.96% women.

With regard to educational level by gender (Table 2), almost 80% of respondents had a basic or medium level of education (47.90% basic, 30.53% medium), while only 20.45% had an academic or university level and 4% had a master’s/doctoral degree. There was fairly homogeneous gender distribution at the basic-medium level, but at the academic or university level, almost 65% were women.

Perception of humanized care

Humanized care behaviors were evaluated in the three dimensions and overall perception. In the PCHE scale, patients chose one of four options (never, sometimes, almost always, always). Table 3 shows the percentages of responses by item and the averages of dimension 1 (D1), defined as the qualities of nursing practice. In D1, aspects such as helping patients experience feelings of well-being and trust are highlighted, ensuring that patients perceive a respectful bond in the nurse-patient relationship. An average of 91% of patients surveyed selected “always” for their perception of this dimension. The item with the lowest score was Q15, "They explain the care using an appropriate tone of voice", for which 88.0% of patients answered “always”.

Table 4 shows the percentages of responses by item and the averages of dimension 2 (D2), defined as "openness to nurse-patient communication”. This dimension refers to a dynamic process, fundamental for growth, change, and behavior, which allows interaction with the patient through communicative skills with the purpose of transmitting a reality and interacting with it. This openness is focused on active listening, dialogue, presence, and understanding with the people being cared for. This dimension has the least valued item of the scale, Q12, "They tell you their name and position before performing the procedure", for which 59.7% responded “always”, 14% “almost always”, 16.8% “sometimes”, and 9% “never”. For the remaining items, 79 to 87.4% of respondents selected “always” regarding their perception of humane care in this dimension, with an average of 81.4%.

Table 5 shows the percentages of responses by item in dimension 3 (D3), defined as "willingness to care". This dimension refers to someone’s temperament in response to a request by a person in need of care, which is not limited to an act of observing, but requires an immersion in their reality to discover their needs and strengthen the bond that unites the two in care. An average of 87.8% of those surveyed chose “always” with regard to how they perceive care. This dimension has the item with the highest value, Q30: "They tell you that when you want something, you can call", for which 99.4% of patients indicated “always”

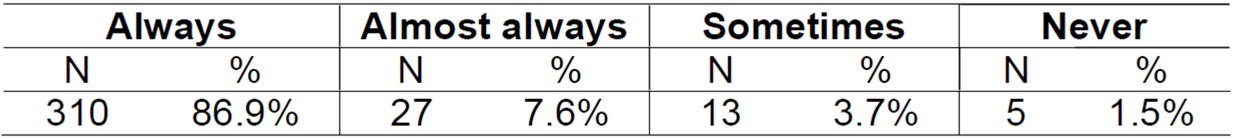

In the category “overall perception of patients” (Table 6), humanized care behaviors were evaluated in the three dimensions. It was found that 86.9% of respondents said they “always” received humanized care, 7.6% “almost always”, 3.7% “sometimes”, 1.5% and “never”.

Another way to determine the perception of humanized care is according to a score in three ranges (good, moderate, bad). Based on this format, more than 90% of respondents hospitalized patients scored their perception in all dimensions as “good”. Dimension 2 (D2), "openness to nurse-patient communication", has the worst score with 91.9%, and dimension 1 (D1), "qualities of nursing practice", has the highest score with 96.6% (Table 7).

Level of patient satisfaction

The importance of knowing the patient's perspective on services has been recognized since the 1980s and has increased since then13. Satisfaction is commonly associated with quality, which is a broad requirement, traditionally focused on the institution and now extended to the perspective of users and workers14. It is made up of three elements: perceived performance, user expectation, and satisfaction level.

The instrument used in the present work was an institutional survey that assessed the three elements in 11 items (Figure 2) evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale. Item 2 (PSAT2), “you were explicitly informed about your rights”, is the lowest rated item with an average of 4.1 and item 10 (PSAT10) is the highest rated with an average of 4.8. It is noteworthy that the overall satisfaction results show a very high level of satisfaction, with an average of 4.6 out of 5, in line with item 12, "perceived level of satisfaction", which has an average of 3.8 out of 4.

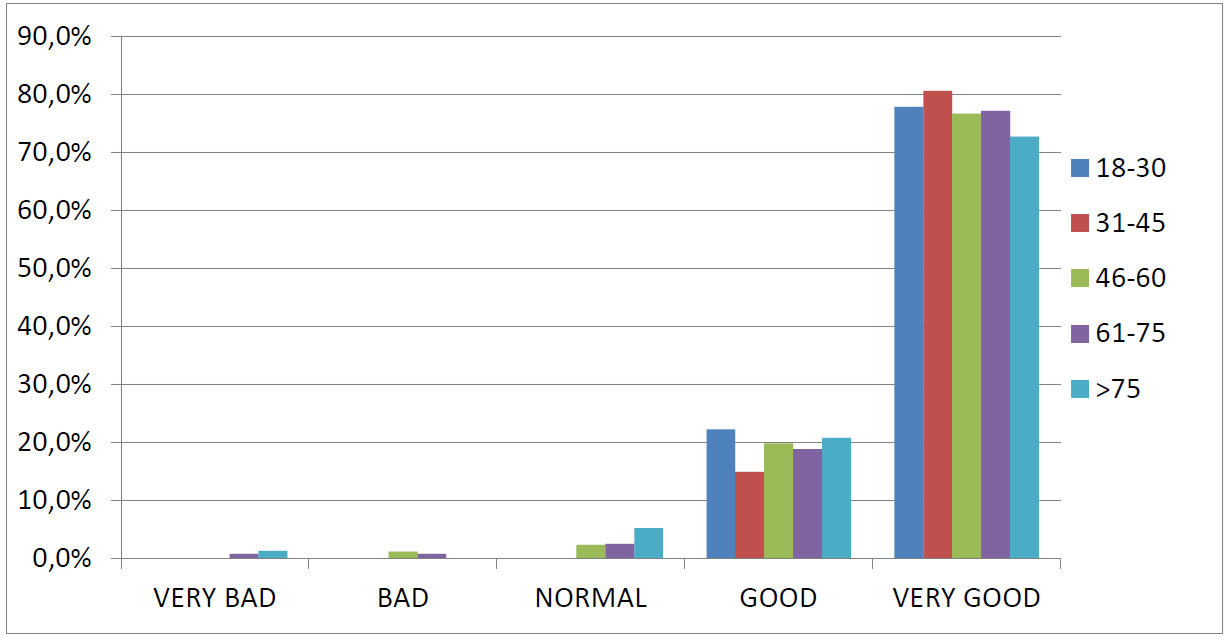

If we cross-reference the satisfaction results with gender (42.3% men vs. 57.7% women) there are no noticeable differences, just as there are no differences between satisfaction and age range (Graph 3). The best results (5 points) vary between 72.7% for the age range >75 years, compared to 80% for 31-45 years, the range with the best satisfaction scores. The worst result (1 point) is also shown by the age range >75 years, although only 1.3% rate satisfaction with such a low average. The results for satisfaction by marital status are not representative, as there is no homogeneity between married and other statuses.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine the perception of hospitalized patients regarding the humanized care provided by nurses, identify their sociodemographic variables, and gauge their degree of satisfaction with the care received.

First of all, the study population was a homogeneous sample in terms of gender, despite having more woman than men. These results agree with those of authors such us Monje et al.1, Eugenio et al.15, Romero-Massa et al.16, and Valdivia17. As those authors maintain, these data are in line with the world population, where we find a higher percentage of women than men.

In terms of marital status, married is the dominant status compared to the others, and it turns out to be a very homogeneous group between both genders. The marital status widowed shows a higher percentage of women than men, with 85.96%. This may be due to the longer life expectancy for women than men. It should be noted that the minority group was divorced, coinciding with a previous study by Valdivia17.

In our study, the level of basic-medium education has a higher incidence than the rest, in contrast to the data obtained for academic/university and master's/doctorate education, which have a lower incidence. Eugenio et al.15 got different results from ours; their study showed higher technical and university education levels than basic and medium.

The Perception of Humanized Nursing Care Behaviors Scale (PCHE) 3rd version divides the humanized care provided by nursing staff into three dimensions: qualities of nursing practice (D1), openness to nurse-patient communication (D2), and willingness to care (D3).

In the present study, D1 was rated the highest and D2 the lowest. These data are similar to those obtained in other studies16,17, in which D1 had the highest value, but ours differ because D3 had the lowest score. Regarding the overall perception of care, more than 85% of patients responded "always", which also coincided with other results18,19, although the percentage is slightly higher in the present study6,8,9.

In addition, the PCHE instrument indirectly evaluates the rights and duties that people have related to their own health: the right to dignified treatment (items 4, 5, 12, and 24); the right to companionship, spiritual assistance, and culturally relevant care (items 17 and 23); and the right to autonomy (items 19 and 29). These rights and duties are reflected in Law 41/2002 of 14 November 2002, a basic law regulating patient autonomy and rights and obligations regarding clinical information and documentation at the national level, and Law 8/2003 of 8 April 2003, on the rights and duties of people in relation to health at the autonomous community level. For all mentioned items, most of our results indicated "always".

Furthermore, we also measured the level of patient satisfaction using a Likert scale. In the present study, we got an average score of 4.6 out of 5, with the highest score for item 10 of 4.8 out of 5 and the lowest score for item 2 of 4.1 out of 5. The average score, referring to item 12, was 3.8 out of 4. The results shower a higher degree of patient´s satisfaction vs similar studies that have shown significantly lower scores in satisfaction16, and they are very similar between the age ranges under study.

We believe that certain items, such as 2 and 3, could be improved since they are below the average for satisfaction in our study. Overall, the noTable finding of the present work is that despite the health crisis patients were exposed to, the results of humanized nursing care and patient satisfaction are very successful according to the hypothesis proposed in the study. A study on humanized care indicated that this perception also depends on the circumstances of the modality and the time and place of the events17. So, it is possible that patients who have experienced a health crisis have considered the context of the pandemic.

There is controversy in the opposite perception, the humanized behavior that nurses believe they can contribute. Despite studies supporting a great deal of resilience in nursing and a spirit of professional dedication to overcome difficulties, a low perception of humanized care by nurses themselves has been shown18. Therefore, there are curious discrepancies in the perception of humanized care among nurses or caregivers and patients receiving such care, as demonstrated by a study with the PCHE tool19. In contrast to Leininger´s idea, quoted by MacFarland, that "culturally congruent care is what leaves the patient convinced that they receive good care"20, humanized care means more than getting a good deal or having satisfaction; it also means that "the other" needs to be careful so that the nursing team and the patient get great results. It is what the patient and family perceive, as well as what the professional and the team that delivers care perceive”8.

We must also keep in mind that nurses face new challenges in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, with effects from the intensive work that exhaust nurses physically and emotionally. We think that a future line of research could be to study the perceptions of behaviors humanized by nurses in our hospital, and investigate both types of perceptions again outside the context of the health crisis, so we can compare them with and without the pandemic context.

Additionally, we propose developing humanized care strategies among professionals, which should be led by nurses and carried out with a biopsychosocial approach in order to avoid the technicalization of care. In the same way, it is also necessary to know the level of university training that future nursing professionals will receive to highlight its importance.

Limitations

While the present manuscript provides valuable information about the patient´s degree of satisfaction regarding the nurse care received during their hospital stay, the study has certain limitations. Due to the pandemic situation, we had to conducted telephone interviews instead of face to face conversations, and we do not know if that might have influenced the responses.

Also, the sample population had geographic boundaries, so the results and conclusions of our study cannot be generally extrapolated.

CONCLUSIONS

We had a homogeneous sample, even though there were woman than men, and more representation in the age range 61-75 years. In the population under study, the predominant marital status as married and the minority was divorced, and the level of education was mainly basic-medium at almost 80%.

The perception of humanized care was evaluated by the PCHE 3rd version, whose items are divided into three categories or dimensions: qualities of nursing practice (D1), openness to nurse-patient communication (D2), and willingness to care (D3). For D1, “always” was chosen by 91.2% of respondents, for D2 it was chosen by 81.4%, and for D3, it was chosen by 87.8%. The average value for overall perception of “always” was 86.9%.

Patient satisfaction was evaluated with an institutional survey, obtaining an average score of 4.6 out of 5. The lowest score was 4.1 on item 2, and the highest was 4.8 on item 10. The perceived level of global satisfaction scored 3.8 out of 4 on item 12.

With our results, we identified the strengths and weaknesses of the variables studied, but the noTable finding of the present work is that despite the health crisis patients were exposed to, the results on humanized nursing care and patient satisfaction are very successful, according to the hypothesis presented in the study. It is possible that patients considered the pandemic context, but undoubtedly the results show indirectly that nurses continue to develop a spirit of dedication and resilience to overcome difficulties with the purpose of promoting patient well-being.

Regarding the quality of care and humanized behaviors, the literature reviewed shows that it is the perception of patients and families, as well as professionals and teams that deliver care, and this finding is the basis for a very important future line of research for us.

The Nursing Now campaign has shown the world the value of nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic. We want to contribute with our investigation too, and provide real data that justify the great role of nurses in society.

REFERENCIAS

1. Monje P., Miranda P., Oyarzún J:, Fredy Seguel P. , Flores E. Perception of humanized nursing care by hospitalized users. Ciencia y Enfermeria. 2018;24:1-10. [ Links ]

2. Kheokao J., Krirkgulthorn T., Umereweneza S., Seetangkham S. Communication Factors in Holistic Humanized Nursing Care: Evidenced from Integrative Review. Journal of MCU Peace Studies. 2019;7(3):609-27. [ Links ]

3. Urra M.E., Jana A., García V. Algunos Aspectos Esenciales Del Pensamiento De Jean Watson Y Su Teoría De Cuidados Transpersonales. Ciencia y enfermería. 2011;17(3):11-22. [ Links ]

4. Marriner Tomey A., Raile Alligood M. Modelos y teorías en enfermería. 6a. Elsevier, editor. España; 2014. [ Links ]

5. Button D., Harrington A., Belan I. E-learning & information communication technology (ICT) in nursing education: A review of the literature. Nurse Education Today. 2014;34(10):1311-23. [ Links ]

6. Hung H.Y, Huang Y.F., Tsai J.J., Chang Y.J. Current state of evidence-based practice education for undergraduate nursing students in Taiwan: A questionnaire study. Nurse Education Today. 2015;35(12):1262-7. [ Links ]

7. Liu Q., Luo D., Haase J.E, Guo Q., Wang X., Liu S., Xia L., Liu Z., Yan J. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e790-98. [ Links ]

8. McFarland M. Teoría de la diversidad y de la universalidad de los cuidados culturales. Modelos y teorías en enfermería 6a ed. Madrid. 2007. 472-498 p. [ Links ]

9. Busch I.M., Moretti F., Travaini G., Wu A.W., Rimondini M. Humanization of Care: Key Elements Identified by Patients, Caregivers, and Healthcare Providers. A Systematic Review. Patient. 2019;12(5):461-74. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00370-1 [ Links ]

10. Pereira A., Souza Da Silva R., De Camargo C.L., Ribeiro De Oliveira R.C. Volviendo a los planteamientos de la atención sensible. Enfermería Global. 2012; 25.http://revistas.um.es/eglobal/article/view/eglobal.11.1.143161 [ Links ]

11. Castro M., Zeitoune R., Tracera, G., Moraes K., Batista K., Nogueira M. Humanization in the work of nursing faculty. Revista brasileira de enfermagem. 2020;73(1):e20170855. [ Links ]

12. González-Hernández OJ. Validez y confiabilidad del instrumento "Percepción de comportamientos de cuidado humanizado de enfermería 3ª versión". Aquichan. 2015;15(3):381-392. DOI: 10.5294/aqui.2015.15.3.6 [ Links ]

13. Bruce J. Implementing the user perspective. Studies in Family Planning. 1980;11(1):29-33. [ Links ]

14. Diprete E. Garantía de la Calidad de la Atención de salud en los países en desarrollo. 717th ed. Bethesda; U. R. C.; 2002. [ Links ]

15. Eugenio Rojas K.D., Ortiz González M., Triviño Bermúdez M., Velasco Peña E.A. Percepción Del Cuidado Humanizado En Profesionales De Enfermería En Una Institución Prestado De Servicio De Salud En Urgencias. 2018; Available from: http://repository.ucc.edu.co/bitstream/ucc/7648/2/2018_Cuidado_Humanizado_Profesionales.pdf [ Links ]

16. Romero-Massa E., Contreras-Méndez I., Pérez-Pájaro Y., Jiménez-Zamora V. Cuidado humanizado de enfermería en pacientes hospitalizados. Cartagena, Colombia. Revisata Ciencias Biomédicas. 2013;4(1):60-8. [ Links ]

17. Valdivia Cornejo M.J. Percepción del cuidado humanizado y nivel de satisfacción en pacientes de área observación, Emergencia- Hospital Honorio Delgado. Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa; 2019. [ Links ]

18. Ceballos Vásquez P. Desde los ámbitos de enfermería, analizando el cuidado humanizado. Ciencia y Enfermeria. 2010;16(1):31-5. [ Links ]

19. Espinoza Medalla L., Huerta Barrenechea K., Pantoja Quiche J., Velásquez Carmona W., Cubas Cubas D., Ramos Valencia A. El cuidado humanizado y la percepción del paciente en el Hospital EsSalud Huacho. Octubre de 2010. Ciencia y Desarrollo. 2011;13:53. [ Links ]

20. Acosta Revollo A., Mendoza Acosta C. A., Morales Murillo K., Quiñones Torres A.M. percepción del paciente hospitalizados sobre el cuidado humanizado brindado por enfermería en una IPS de tercer nivel. Cartagena 2013. Vol. 66. Corporación Universitaria Rafael Núlez. Facultad de ciencias de la Salud; 2013. [ Links ]

Received: May 05, 2021; Accepted: July 12, 2021

texto en

texto en