Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 no.66 Murcia Abr. 2022 Epub 05-Maio-2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.489911

Originals

Analysis of the psycho-emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among nursing professionals

1 Enfermera. Centro de Salud de Calaceite, Alcañiz, Teruel. España. alba1986_7@hotmail.com

2 Enfermera del Servicio de Cardiología. Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza, España.

3 Farmacéutico Titular Farmacia Comunitaria Solano, Huesca, España.

4 Enfermera Especialista en Enfermería Obstétrico-Ginecológica. Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa. Docente del Grado de Enfermería en la Universidad San Jorge. Zaragoza, España

5 Phd. Docente del Grado de Enfermería en la Universidad San Jorge, Zaragoza, España.

6a Técnico en Bioestadística en el Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud (IACS), Zaragoza.

6b Profesor asociado en la Universidad de Zaragoza (Unizar), Zaragoza, España.

Introduction:

The 2019 new coronavirus disease was diagnosed in December 2019 in Wuhan (China), declaring a global pandemic in March. Epidemics generate fear, anxiety and anguish amongst the general population, and amongst health personnel (especially in nursing), the COVID-19 pandemic has been no exception. The objective of the study was to analyze the psycho-emotional impact of COVID-19 among nurses in the province of Huesca.

Methods:

Descriptive cross-sectional study, approved by the Ethics Committee. With prior informed consent, anonymously and voluntarily, the participants filled out a questionnaire on psychological symptoms, using the DASS-21© scale, the ISI©, the MBI© and the FCV 19S© scales, also collecting sociodemographic, professional and COVID-19 associated variables.

Results:

The sample consisted of 196 nurses. 16,8% presented depression, 46,4% anxiety, 22,4% stress and 77,6% insomnia, with higher levels amongst the eldest, permanently employed, more experienced nurses, risk comorbidities, less leisure and more hours of work. Psychological Exhaustion (Burnout Syndrome) was detected in 50,5% and fear of coronavirus-19 in 46,9%, variables such as having a position in a COVID-19 unit, more experienced, being a Specialized Care Nurse and not living with family members, triggered greater symptomatology. Regression analyzes showed that the COVID-19 infection was a common risk factor.

Conclusions:

The SARS CoV-2 health crisis has generated a relevant psychological impact among nursing staff. Therefore, they should be offered psychological support to reduce it and thus ensure their mental health and the valuable care they provide.

Keywords: COVID-19; Nursing staff; Mental health; Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders; Burnout Psychological Exhaustion; Fear

INTRODUCTION

Background and current status of the issue

On December 31, 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health and Sanitation Commission (Hubei, China) reported an outbreak of 27 cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology1,2. On January 7, 2020, the Chinese authorities identified it as the causative agent of the outbreak of a new type of virus from the Coronaviridae family, which would later be officially named Coronavirus type 2 that causes Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease infected by this virus would be called Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)2,3.

The new coronavirus spread very quickly across all continents, generating the largest outbreak of atypical pneumonia in the world1. In Spain, the first case of COVID-19 was notified in Palma de Mallorca, on January 31, 2020 and the first positive case was confirmed in Aragon on March 5, 2020; spreading rapidly throughout the country1,3. Due to its rapid expansion, the World Health Organization (WHO) on January 30, 2020, declared the outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Interest (ESPII), to name it afterwards on March 11, 2020, a Pandemic1)(2)(4. The COVID-19 pandemic has put the health system of many countries to the test and, of course, the Spanish health system as well4. In order to face the matter, many of the governments have applied exceptional emergency measures, specifically, the Spanish government on March 14, they decreed a state of alarm to manage the situation, imposing severe measures of confinement, quarantine and social isolation2,4. With more than 209 million confirmed cases and more than 4 million deaths worldwide, SARS CoV-2 has become an unprecedented health crisis, which has demonstrated high person-to-person transmissibility, involving infections in health professionals and therefore a high risk of spread5,6.

It has been shown that health security crises often generate stress and/or anguish amongst the general population, as well as amongst health personnel, by feeling fear of acquiring the virus and dying as a result of the infection1,4, this in addition to the fact that according to data provided by the Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare, just 13 days after declaring the state of alarm in Spain, cases among health professionals constituted 14% of the total of those infected, which triggered relentlessly among these workers a great concern about the high risk of possible infection to which they are exposed7.

After declaring the WHO a COVID-19 pandemic, various investigations have come to light on its effects on the mental health of health personnel, as evidence of this, several authors point out that health workers frequently fear spreading the infection to their family members, friends and/or colleagues and, likewise, they experience symptoms of anxiety, stress, anguish, depression or clinical insomnia, that in turn has long-term psychological repercussions1)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7. Due to all of this beyond the medical risk, the psychological impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has generated is truly indispuTable8)(9)(10.

In Spain, the first study that explored the psycho-emotional impact of SARS-CoV-2 on health personnel was carried out by Dosil Santamaría M (and others), stating that the pandemic caused symptoms of anxiety, depression, stress and insomnia among them10. Another of the investigations carried out in our country was that of Erquicia (and others), after identifying an important outbreak of COVID-19 in Catalonia (specifically in the Conca de Ódena region), corroborating that a significant percentage of health professionals from the hospital of that region suffered serious psychological distress, especially the nursing staff11.

During the current pandemic, nursing professionals have experienced unprecedented patient death rates, even within a profession in which death is expected, at the same time they have had to face difficult working conditions, such as long working hours, healthcare overload, reduction of social contact, among others, all constituting a perfect storm of circumstances that put their physical health, mental health, well-being and also their ability to do their job at risk, accelerating the appearance of symptoms of anxiety, fear, depression and/or post-traumatic stress disorder4)(12)(13)(14. As a reflection of this, various articles have been published that have explored the psychological health and emotional well-being of nursing staff during COVID-19, reaffirming in all of them serious negative consequences of the pandemic on their mental health: anxiety, stress, etc.7)(9)(11)(12)(13)(14.

In response to this, several recent investigations agree in pointing out that it is very important to protect the mental health of health professionals, since it is essential in the adequate fight against the virus, and at the same time to maintain their health, safety and well-being: "take care of the one who takes care of others”3)(4)(7)(10)(12)(13.

Study justification

Although there are several systematic reviews that are published they have reflected an increase in the widespread presence of stress, anxiety, depression, insomnia, compassion fatigue or burnout syndrome (Psychological Exhaustion) among healthcare professionals during the SARS CoV-2 virus pandemic1)(3)(7, there are few studies focused on the psychological well-being of the personnel, since researchers have focused mainly on clinical or epidemiological aspects of the virus; paying less attention to the psychosocial effects and/or the impact of the current COVID-19 disease pandemic has on the mental health of different vulnerable population groups1)(3)(14)(15)(16)(17)(18. The lack of attention to the psycho-emotional impact of the pandemic on a sensitive population, such as the nursing personnel located on the front lines of the struggle, has been the main reason for conducting the present study14,16.

Reviewing articles published about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of health professionals, we detected that most were carried out in China (the well-known epicenter of the pandemic), studies on this topic are quite limited in our country16-19, in addition, specifically in the Healthcare Section of Huesca and Barbastro; there is no evidence of any work regarding this topic, all of this has encouraged us to direct our study towards exploring mental health before the pandemic of nurses in that region. To point out that there is now an urgent need to first investigate the repercussions that COVID-19 is having on the mental health of nurses, and following the final results, generate interventions that protect their mental health and emotional well-being, in order to avoid all the problems listed above having an impact on the quality of care that these professionals provide to their patients, with the maps of mental health problems (our study) being useful tools for the design of these plans7)(10)(13.

The general objective of this study was to analyze the psycho-emotional impact caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on the nurses who provide healthcare to patients during the SARS-CoV-2 virus outbreak in some of the health care centers in the province of Huesca by answering an online questionnaire. The specific objectives have been to determine their degree of depression, anxiety, stress, insomnia, burnout and fear of COVID-19, in addition to analyzing whether there were statistically significant differences between the dependent variables based on the different independent variables collected.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Type of study, setting and target population

It is a descriptive cross-sectional study. The study scope was made up of Primary Care Nursing, Specialized Nursing and Social Healthcare Centers. The target population was made up of Nurses from Primary, Continuous, Specialized healthcare from Social and Healthcare Centers. It was also made up of Specialists and Resident Internal Nurses, who work for healthcare or management work during the SARS CoV-2 pandemic in some of the healthcare centers of the province of Huesca.

Sample size and sample selection criteria

The sample size was calculated based on the census of registered nurses (1510), establishing the representative sample at 179 nurses.

Inclusion criteria: nursing professionals who were active during the COVID-19 pandemic, working in healthcare and/or management work in some of the health centers in the province of Huesca. They read on the institutional website of the Official College of Nursing in Huesca, the explanatory text of the study, its information sheet and voluntarily granted their consent to participate.

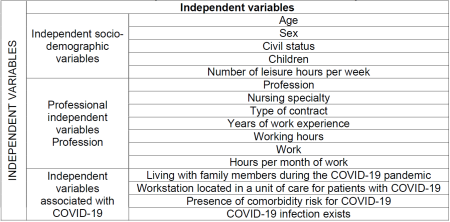

Study variables

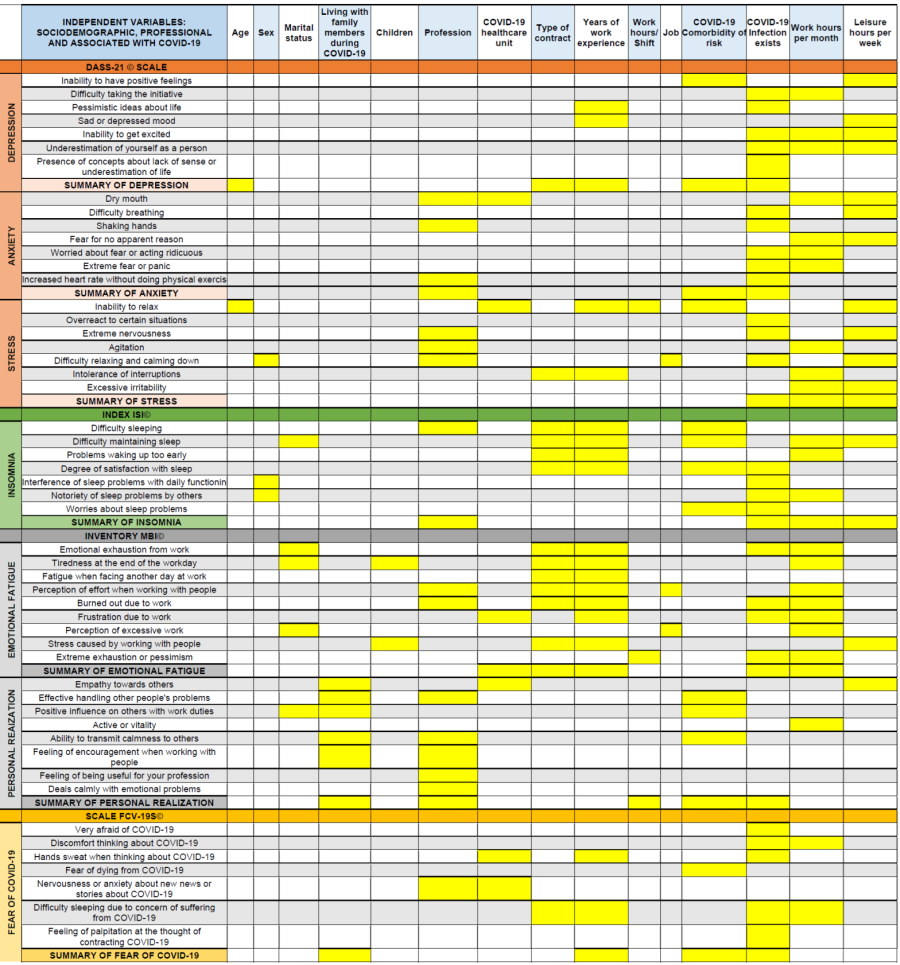

Independent variables: the independent variables of interest were obtained through an “ad hoc” questionnaire, a total of 16 were collected, distributed in 3 groups: 5 sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, children and number of hours of leisure time available a week), 7 professional variables (profession, nursing specialty, type of contract, years of work experience, working hours, job and working hours per month) and 4 variables associated to COVID-19 (living with family members during the pandemic due to COVID-19, work position located in a unit of care for patients with SARS CoV-2, presence of comorbidity risk for COVID-19 and current or past COVID-19 infection) ( Annex I ).

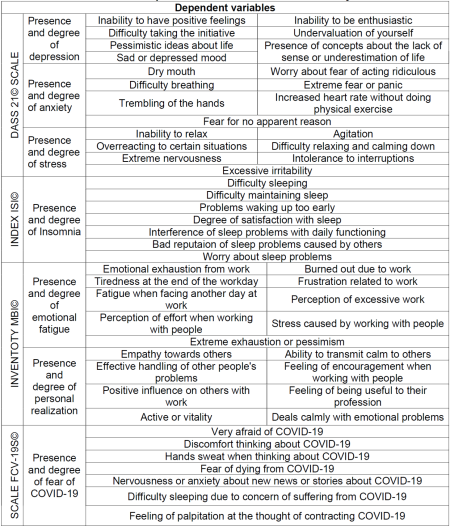

Dependent variables: a total of 52 variables were collected, obtained through 4 questionnaires: the DASS-21© scale composed of 21 variables to assess the presence and degree of depression, anxiety and stress10)(11)(14)(16, the ISI© index formed by 7 variables to evaluate the presence and degree of insomnia3)(16)(17)(18, the MBI© inventory structured in 17 variables to evaluate the presence and degree of Emotional Fatigue (EF) and Personal Realization (PR)16)(19)(20 and the FCV-19S© scale made up of 7 variables to assess the presence of fear of coronavirus-19 (1) ( Annex II ).

Data collection and instruments used

The methodological tool used to analyze the psycho-emotional impact was a self-administered online, anonymous and voluntary questionnaire, released on the institutional website of the Official College of Nursing in Huesca, designed through the Google Forms platform1,8. Participants were asked to submit their answers between April 14 and May 31, 2021. Afterwards, these answers were uploaded to an Excel database, and then sent to the JAMOVI® program.

The questionnaire designed specifically for this study contained 5 blocks, the first block asked about sociodemographic, professional and COVID-19-associated characteristics of the sample, and the other 4 blocks consisted of 52 questions from 4 validated scales with robust psychometric properties: the DASS© scale, FCV-19S©, the ISI© index and the MBI© inventory3)(16)(17:

- Scale of depression, anxiety and stress (Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, DASS-21©): this scale was validated in several studies, languages and countries3)(8)(10)(20. Chew NWS (and others), Tan BYQ (and others) and Wang C (and others), have already used it to investigate the psychological responses of health workers in the COVID-19 pandemic3)(16)(17. The DASS-21© consists of 21 items, which are distributed into 3 subscales, with 7 questions each. Each item is valued from 0 to 3 being: Never = 0; Sometimes = 1; Almost always = 2 and Always = 3. It offers a total score between 0 and 42 points, and the results must be interpreted by subscale. Depression subscale: 0-9 = Normal; 10-12 = Mild depression; 13-20 = Moderate depression; 21-27 = Severe depression and 28-42 points = Extremely severe depression. Anxiety subscale: 0-6 = Normal; 7-9 = Mild anxiety; 10-14 = Moderate anxiety; 15-19 = Severe anxiety and 20-42 points = Extremely severe anxiety. Stress subscale: 0-10 = Normal; 11-18 = mild stress; 19-26 = Moderate stress; 27-34 = Severe stress; 35-42 = Extremely severe stress8)(11)(16)(20.

- Insomnia Severity Index (ISI©): previous studies support that both the English and Spanish versions have good psychometric properties3,21. Kang L (and others), Lai J (and others) and Zhang W (and others), used it in their research on the mental health of healthcare personnel during SARS CoV-23)(6)(18)(21. It is a simple, short questionnaire, made up of 7 items. To rate them, a 5-point Likert scale is used, which are valued: Items 1, 2 and 3: Nothing = 0; Mild = 1; Moderate = 2; Serious = 3 and Very serious = 4. Item 4: Very satisfied = 0; Satisfied = 1; Neutral = 2; Not very satisfied = 3 and Very dissatisfied = 4. Items 5, 6 and 7: Not at all = 0; A little = 1; Something = 2; Much = 3; and Very Much = 4. The total score obtained is from 0 to 28 points: Absence of insomnia = 0-7; Mild insomnia = 8-14; Moderate insomnia = 15-21 and severe insomnia = 22-48 points16)(18)(21.

- Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach Burnout Inventory, MBI©): this has been the most widely used validated instrument by the research community to assess Burnout Syndrome (BS) in different healthcare contexts3)(17)(22. It consists of 22 items that are valued with a Likert scale that goes from Never = 0, to Everyday = 6, it has 3 subscales: EF, PF and Depersonalization. In the present study, its adaptation to Spanish by N. Seisdedos was used, using only 2 subscales: EF and PR22. EF subscale: offers a total score between 0-54 points, a score greater than 26 would indicate signs of SB, the degree of SB is interpreted as follows: low level = 0-18; medium = 19-26 and high = 27-54. PR subscale: the maximum score is 48, a score lower than 34 would already indicate possible SB, the degree of SB is interpreted as follows: low level = 0-33; medium = 34-39 and high = 40-48 points16)(19)(20.

- Scale of fear of COVID-19 (Fear of COVID-19 Scale, FCV-19S©): this scale was created a short time ago (March 2020) by Ahorsu DK (and others). Its authors reported that it is a very valid and reliable instrument to assess fear of COVID-191,3. For our study, the translation of Monterrosa Castro A (and others)1) was chosen. Each question is answered Likert type with 5 options that assign the points as follows: Totally disagree = 1; Disagree = 2; Neither agree nor disagree = 3; Agree = 4; Strongly agree = 5. According to published evidence, the study considered the first 3 options as negative responses (not fear of COVID-19) and the other 2 as positive (yes fear)1.

Statistical analysis of the data

The data was analyzed using the JAMOVI® statistical program. Qualitative variables were presented by absolute frequency distribution and in %. The only quantitative variable (age) was explored with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov conformity test, which was expressed using indicators of central tendency and dispersion: the average and Standard Deviation (SD), and since it did not follow a normal distribution, it was also presented by median and quartiles. The association between the result variables (the total sum) and the rest of the variables was investigated by means of hypothesis contrast tests as these variables did not follow a normal distribution, by comparing proportions when they were qualitative (chi-square, Fisher's exact test), with comparisons of distributions when they were quantitative and by a non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskall-Wallis test). The statistical analysis was completed by executing multivariate logistic regression models taking as dependent variables the total sum of the DASS-21©, ISI©, MBI© and FCV-19S©, and as independent variables those that were significantly simple or which, could turn out to be confusing variables. To carry out the analysis, all polycotomic variables were transformed into dichotomous variables. The effects were considered significant if p <0,05, and the p values were two-tailed5)(21)(23.

Ethical-legal considerations of the study

This study was carried out in compliance with the requirements of Law 14/2007, of July 3, on Biomedical Research and the applicable ethical principles. The ethical approval of the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Autonomous Community of Aragon (CEICA) reflected in its act nº 07/2021.

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis of the independent variables

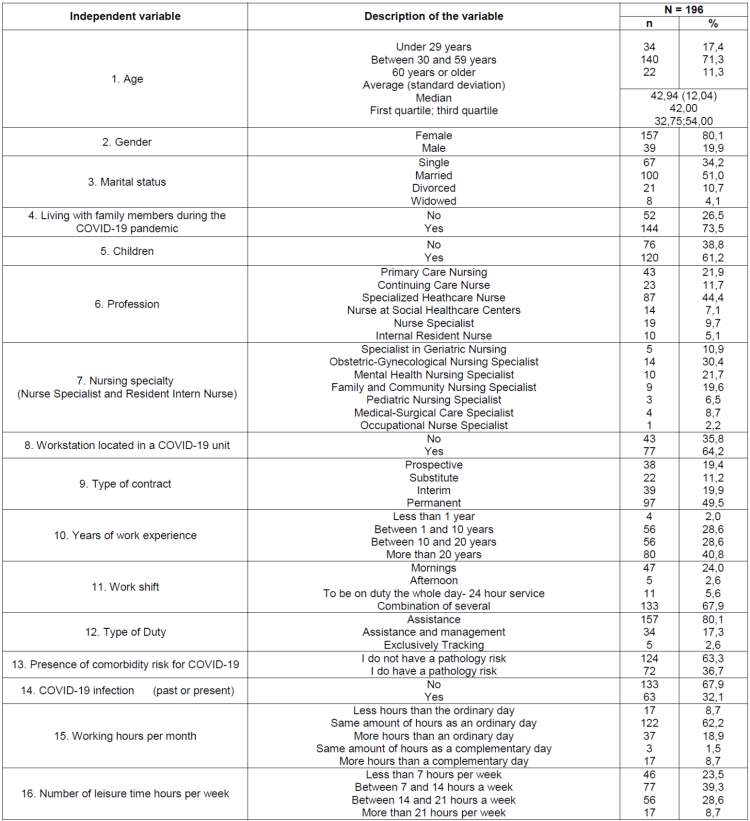

The sample was made up of 196 participants who filled out the online questionnaire. The data of the independent sociodemographic variables show that of the 196 participating nurses: 39 were men (19,9%) and 157 women (80,1%). The age of these nurses ranged between 22 and 65 (42,94 ± 12,04) years. More than half were married (n=100, 51,0%) and had children (n=120, 61,2%), on the other hand, 77 of them (39,3%) said they had between 7-14 leisure time weekly hours.

Regarding the results of the independent professional variables, most of the participating nurses belonged to the Specialized Care setting (n = 84, 44,4%), followed by the Primary Care setting (n = 43, 21,9%). According to the specialty developed by the respondents, the data obtained showed that most of the specialist nurses, specifically 30,4% were studying and/or developing the specialty of Obstetric-Gynecological Nursing, 21,7% the specialty of Mental Health and 19,6% were studying the Specialty of Family and Community Nursing. About 50% of the respondents had a permanent job (n=97, 49,5%). Most of the participating nurses had work experience of more than 10 years (n=136, 69,4%), with 40,8% of the sample (n=80) having more than 20 years of professional experience. On the other hand, the vast majority indicated having a working schedule consisting of a combination of several shifts (n=133, 67.9%) and performing healthcare work (n=157, 80,1%). Regarding the monthly hours of work, a large part of the nurses affirmed that they work the hours that are established as a normal work day (n=122, 62,2%).

The results obtained in the independent variables associated to COVID-19 showed that more than 50% of the nurses in the sample lived with relatives during the COVID-19 pandemic (n=144, 73,5%). Most of the Specialized healthcare Nurses (SHN) indicated that their work position was located in a unit of care for patients with COVID-19 (n=77, 64,2%). In contrast to this, only 36,7% (n=72) of the sample said they had a comorbidity risk for the SARS CoV-2 virus, along with the fact that only 32,1% (n=63) said they currently suffer or have suffered from the COVID-19 infection (Table 1).

Descriptive analysis of the dependent variables

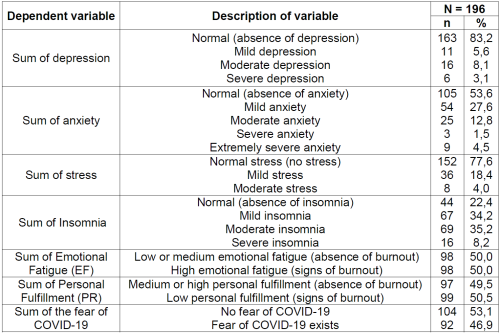

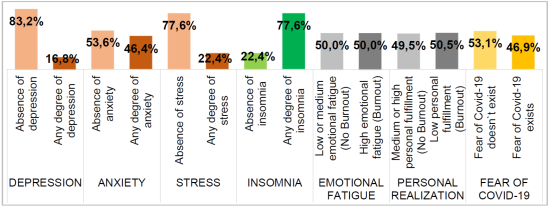

Using the predefined cut-off points in the DASS-21© scale scoring system for the purpose of evaluating the degree of depression, anxiety and stress among the nurses under study, we found depression in 33 (16,8 %), anxiety in 91 (46,4%) and stress in 44 (22,4%). The average score on the DASS-21© depression subscale was 6,46. Of the 33 nurses who tested positive for depression, 66,7% (n=22) were classified as moderate to severe depression. The general average score on the DASS-21© anxiety subscale was 6,50. Of the 91 respondents who tested positive for anxiety, 40,7% (n=37) showed moderate to extremely severe anxiety. In terms of the DASS-21© stress subscale, the average score was 8,52 points, with moderate stress in 8 of the 44 nurses (18,2%) who were positive. In order to study the degree of insomnia in the sample of nurses, based on the criteria of the ISI© index, we were able to detect insomnia in 152 (77,6%). Being the average general score in the ISI© of 12,82. Of the 152 who tested positive for insomnia, 55,9% (n = 85) had moderate to severe insomnia. Using the predefined cut-off points in the MBI© inventory scoring system in order to assess the presence of BS among the nurses object of our study, we observed a high EF in 98 (50,0%) and a low PR in 99 (50,5%) of them, both results reflecting signs of SB. The average score on the EF MBI© subscale was 28,84, and 32,30 on the PR MBI© subscale. Using the cut-off points established on the FCV-19S© scale with the aim of evaluating fear of COVID-19 among the sample, we detected fear in 92 (46,9%), with the mean score on the FCV-19S© scale of 21,54 points (Table 2, Graph 1).

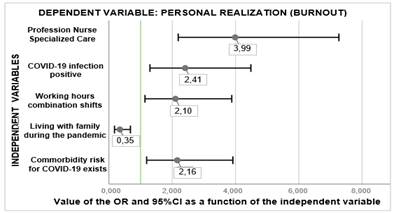

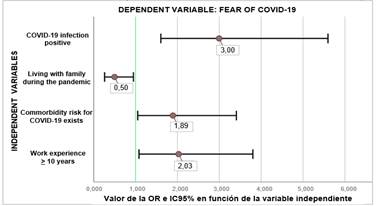

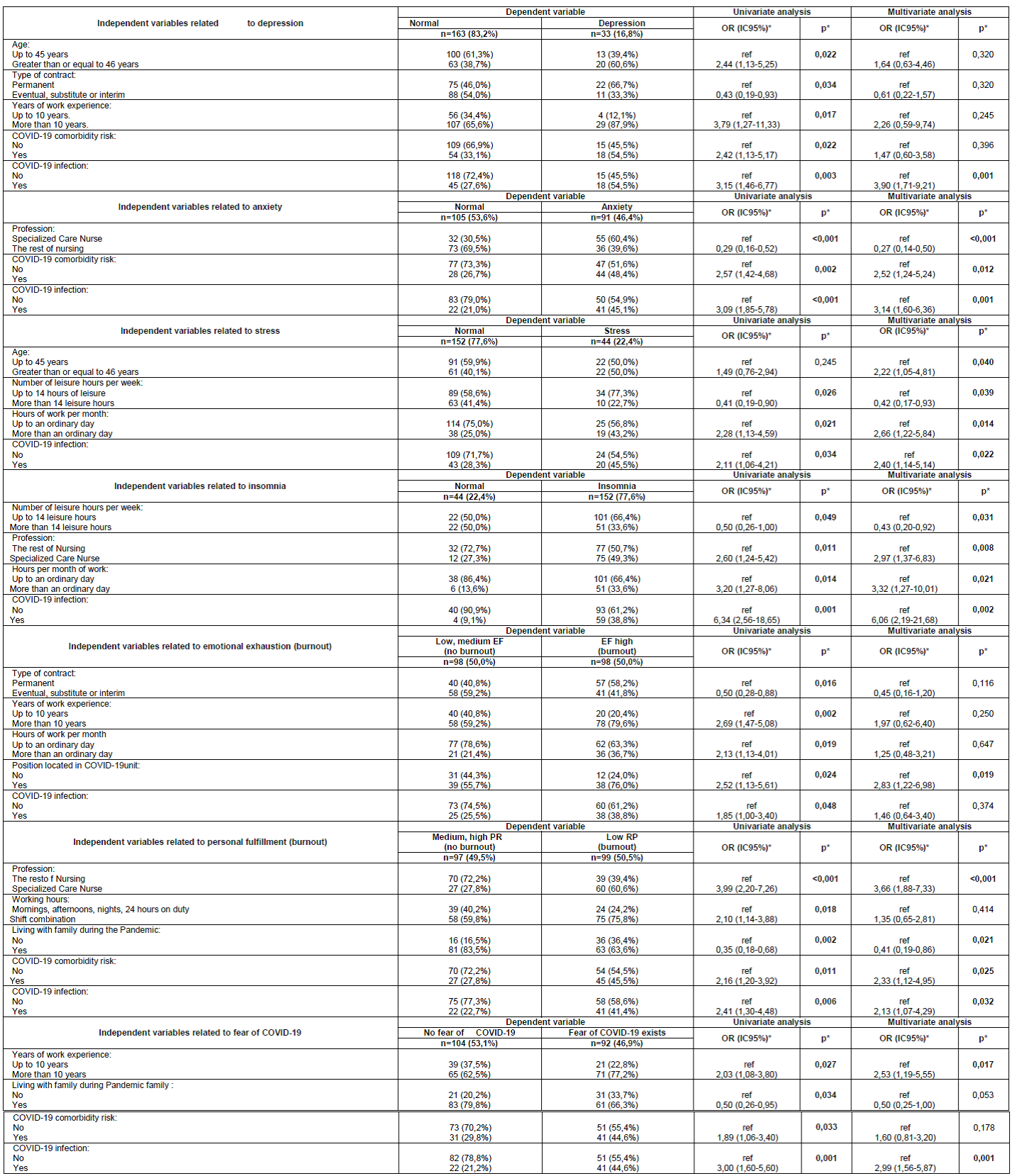

Univariate and multivariate regression analysis for variables related to depression, anxiety, stress, burnout (EF, PF) and fear of COVID-19

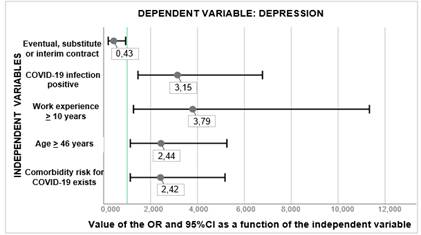

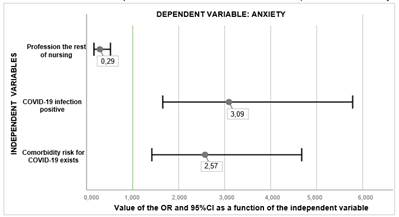

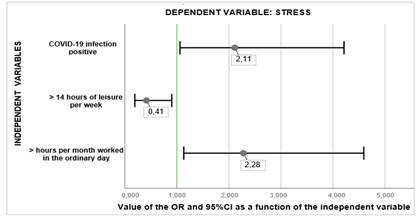

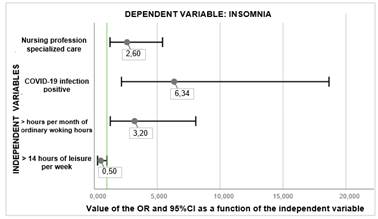

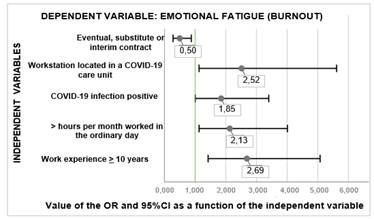

In order to analyze whether there were statistically significant differences between the dependent variables based on the independent variables, univariate and multivariate regression analysis were performed, taking as dependent variables the sum of (new variables created from the results obtained in each of the scales). A total of 29 variables showed statistical significance in the univariate model, 18 of them being confirmed in the multivariate analysis, detecting a new significant difference not previously seen ( Annex III ). The results of the univariate are shown in 7 graphs below:

Nurses who have suffered or are suffering from COVID-19 infection, with work experience of more than 10 years, with an age greater than or equal to 46 years and who have comorbidity risk for COVID-19, have a higher risk of presenting depression. However, those who have a temporary, substitute or interim contract have a lower risk of presenting depression, being a protective factor (Graph 2).

Nurses who suffer or have suffered from COVID-19 and who present risk comorbidity for the virus have a higher risk of presenting anxiety, compared to those who are not specialized care nurse who have a lower risk of anxiety (Graph 3).

Nurses who suffer or have suffered from the COVID-19 infection and who work more hours per month than the ordinary day, have a higher risk of having stress, both of which are risk factors. In contrast, those who have more leisure hours per week have a lower risk of suffering stress (Graph 4).

Nurses who suffer or have suffered from COVID-19, who work more hours per month than the ordinary day and who are specialized care nurse, have a greater risk of having insomnia, however those who have more leisure have a lower risk (Graph 5).

Nurses who have suffered or suffer from COVID-19, with work experience of more than 10 years, who work more hours per month than the ordinary day and whose job is in a COVID-19 unit, have a greater risk of presenting high EF (SB), however those that are not fixed have lower risk (Graph 6).

Nurses who have suffered or are suffering from COVID-19, whose schedule is made up of a combination of shifts, who have comorbidity risk for COVID-19 and who are Specialized Care Nurse, have a higher risk of presenting low PR, compared to those who live with their family during the pandemic who have less risk (Graph 7).

Those nurses with COVID-19 infection, those with comorbidity risk for the virus and those with more than 10 years of experience, have a higher risk of presenting fear of COVID-19. However, those who live with their families during the pandemic have a lower risk of feeling that fear (Graph 8).

Univariate regression analysis by independent variables

In order to analyze whether there were statistically significant differences between the variables, univariate analyses were also performed, taking as dependent variables all the response variables of the questionnaires in addition to the final sums. After analyzing 885 possible associations, a total of 173 statistically significant differences were detected. The independent variable COVID-19 infection was the one in which the greatest number of associations was observed 33, in contrast to the variables age and children, which were in which the least number of associations were detected (only 2 in each one). The results of the univariate regression model revealed that nurses who: have suffered or are suffering from COVID-19 infection, who work more hours per month, with more than 10 years of work experience, whose profession is specialized care, with fewer hours/week of leisure (<14 hours), who present comorbidity risk for the SARS CoV-2 virus, with a permanent contract, that their work position is located in a unit of care for patients with COVID-19, who do not live with their family members during the pandemic, who are married, who perform care work combined with management, who are women, whose working hours are made up of a combination of several shifts, who have children and over 46 years of age, have mental health deficient in the current context of pandemic, that is, COVID-19 has a greater psycho-emotional impact among them, generating symptoms of anxiety, depression, stress, insomnia, burnout and/or fear ( Annex IV ).

DISCUSSION

As a result of COVID-19, nursing personnel are the ones that have been most affected in relation to their mental health due to the particular characteristics of their profession17. Despite the fact that scientific evidence suggests that the psychological burden of the SARS CoV-2 virus is higher among younger health professionals with less work experience5)(8)(11)(17)(24, this association is not fulfilled in the present study, since higher rates of depression, fear and burnout could be observed among older nurses with more work experience, an aspect that could be explained by 2 reasons: on the one hand, the older they are, the more likely it is that the respondents have a family in their care (children and/or parents), which increases the pressure of responsibility and the fear of transferring the virus to their homes and, on the other hand, with more knowledge and experience, there is more awareness of the danger10.

The findings of our study revealed that suffering comorbidities risk for COVID-19 and that working as a Specialized Care Nurse were variables that increased the risk of suffering from depression, anxiety, insomnia, burnout and fear among the/as surveyed, these results coincide with those of Ozamiz (and others) and Zhu Z, (and others) reporting that health professionals with related diseases present higher levels of psychological symptoms in this crisis situation, since it has been shown that coronavirus-19 is more prone to manifest itself more severely among them3)(8)(25.

The greatest psycho-emotional impact detected among first-line professionals (specialized care nurse) coincides with that endorsed by Batalla Martín (and others) and Tan BYQ (and others), who stated that health workers who work on the front line against the virus have poorer levels of health (more psychological symptoms)3,26. To report that the scores obtained on the DASS-21© in this study were higher than those published in previous research on the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of health personnel26,27, this fact could be due to a lower psychological preparation of the health personnel in Spain, in comparison to the exhaustive measures implemented in other countries such as Singapore after their difficult past experience with SARS26. However, it should also be noted that the percentages of stress, depression and anxiety are lower than those reported in other studies conducted in Spain in the initial phase of the pandemic10,11, an aspect that seems to indicate that, although the outbreak of the SARS CoV-2 virus has had an immediate impact on the mental health of the nursing staff, with the passage of time there seems to be a certain phenomenon of psychological adaptation that causes them the harmful effects to be reduced, that is, they adapt to the “new normal situation”14.

In the present study, more than half of the respondents showed signs of burnout, values higher than those reported by Giusti EM (and others) and Barello S (and others)19,20, an aspect that could indicate the lack of conditions and the necessary mental preparation of the nursing staff to face the emergency. Therefore, it would highly be recommended to identify and promote protective factors at the same time (positive attitudes at work, recognition of effort, cohesive teams), to help nursing personnel to mentally face the pandemic20.

It was found that 46,9% of the sample presented fear of COVID-19, a fear higher than that endorsed by Monterrosa Castro (and others) and Ortega Malla AL (and others), so early strategies would be necessary to prevent and treat fear both in the short term. and long-term1,28. Curiously, the analysis revealed more fear amongst those who did not live with their family during the pandemic, an aspect that could be due to their fear of being infected and consequently not being able to respond to their professional duty.

It should be noted that our study offers certainly impressive results in relation to the COVID-19 infection variable, since it was a common risk factor for the 5 psychological symptoms analyzed. These results have relevant implications at the clinical level and at the health policy level, since they suggest that infected nurses are a vulnerable group, presenting a greater psychological discomfort than other professionals. These results are in line with previous research that in the same way supports that the confirming diagnosis of the infection is directly linked to a greater number of psychological disorders, which are considered a risk factor for mental health18.

Regarding the limitations of our study, we consider that the main one is the sample. Although the desired sample was achieved (179), the response rate was only 12,98%, so the results may seem biased, in addition, the fact that it was carried out on nurses practicing in Huesca limits the extrapolated in of our findings to other regions and also other categories of health. The online questionnaires compared to face-to-face interviews are accompanied by several limitations, however, it had to be online to minimize contact between professionals, the study was completed for only 48 days and therefore lacks follow-up longitudinal. On the other hand, inform that we do not start from previous data on the emotional impact of the pandemic in the evaluated sample, so no comparisons could be made.

Despite the previously mentioned limitations, the present study has noTable strengths. First, note that a large number of statistically significant differences were detected (173) and that validated scales were used to obtain the information, aspects that reflect the quality, weight and value of the results. Finally, the greatest strength of the work is that it can turn out to be an excellent starting point to expand the studies in this regard, since it is a novel topic, not many studies have been carried out and the topic is very interesting, based on the great repercussions that nursing mental health can have in the health system, specifically in the Aragonese Health Service where the sample works.

For future research, we suggest the practice of a prospective and randomized longitudinal multicenter study that addresses various health sectors and categories, thus obtaining much more complete information on their psycho-emotional situation in relation to COVID-19, thus being able to extrapolate the results.

Reviewing the trajectory of the health crisis and given the results of our work, we consider that studies should be carried out in the near future to evaluate the psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among those health workers who work in the first line of defense, to know their mental situation, and at the same time generate supportive approaches that are factual based focused on alleviating the identified psychological symptoms28)(29)(30.

Regarding the practical implication that our study has, it should be noted that it could improve the daily work of the nurses in Huesca who struggle every day caring for patients with COVID-19, since the great psycho-emotional impact evidence serves to demonstrate to the managers the urgent and real need to establish guidelines directed towards their emotional well-being.

CONCLUSIONS

According to the results obtained, it is concluded that "the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative influence on the mental health of the nurses working in the province of Huesca". Throughout the study, several statistically significant differences were detected between the variables, so it can be concluded that:

In relation to anxiety, depression and stress, the data obtained show that variables such as longer work time, less leisure time, higher work experience and the presence of comorbidities risk for COVID-19, among others, account for precipitating factors for an alteration in the mental health of nursing professionals in times of COVID-19, therefore they must be taken into account since they can interfere, reducing the quality of care that these professionals provide in the current challenging situation of the pandemic10.

This study shows the need to work and to improve the quality of sleep of nurses, requiring special attention to those who are exposed to more hours of work and who practice in the specialized field.

Regarding BS, half of the sample suffers from signs of BS, an aspect that reflects the complexity of their work (they face death and suffering), so it is concluded that they need to feel valued and recognized, consequently we recommend providing support systems for mental health specialists to alleviate the impact of the current pandemic on both their current and future psychological well-being3,6.

The data obtained suggest that about half of the sample showed fear of COVID-19, which is why it is concluded that despite the passage of time (COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in 2020) it has not mitigated the fear among the nurses28. As a final conclusion, it should be noted that “the psycho-emotional impact that the pandemic has caused on nurses is important and encompasses different spheres, so we consider it very necessary not only to detect it through standardized instruments but also to treat it, to avoid problems in the short term and the long term, since nursing has an irreplaceable and valuable role”7,30.

REFERENCES

1. Monterrosa Castro A, Dávila Ruiz R, Mejía Mantilla A, Contreras Saldarriaga J, Mercado Lara M, Flores Monterrosa C. Occupational Stress, Anxiety and Fear of COVID-19 in Colombian Physicians. MedUNAB. 2020;23(2):195-213. [ Links ]

2. Información Científica-técnica. Enfermedad por coronavirus, COVID-19. Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias Sanitarias; 2020 Abr 17. [ Links ]

3. Batalla Martín D, Campoverde Espinosa K, Broncano Bolzoni M. El impacto en la salud mental de los profesionales sanitarios durante la Covid-19. Rev Enferm Salud Ment. 2020;16:17-25. [ Links ]

4. Buitrago Ramírez F, Ciurana Misol R, Fernández Alonso MDC, Tizón JL. Pandemia de la COVID-19 y salud mental: reflexiones iniciales desde la atención primaria de salud española. Aten Primaria [Internet]. 2021 Ene [citado 10 Ene 2021];53(1):89-101. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2020.06.006 [ Links ]

5. Azoulay E, De Waele J, Ferrer R, Staudinger T, Borkowska M, Povoa P, et al; ESICM. Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):110. [ Links ]

6. Pan R, Zhang L, Pan J. The Anxiety Status of Chinese Medical Workers During the Epidemic of COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Investig [Internet]. 2020 May [citado 10 Ene 2021];17(5):475-480. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2020.0127 [ Links ]

7. Bueno Ferrán M, Barrientos Trigo S. Cuidar al que cuida: el impacto emocional de la epidemia de coronavirus en las enfermeras y otros profesionales de la salud. Enferm Clin [Internet]. 2020 May [citado 12 Ene 2021];31(1):35-39. Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.enfcli.2020.05.006 [ Links ]

8. Ozamiz Etxebarria N, et al. Niveles de estrés, ansiedad y depresión en la primera fase del brote del COVID-19 en una muestra recogida en el norte de España. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2020 [citado 12 Ene 2021];36(4): e00054020. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00054020 [ Links ]

9. García Fernández L, Romero Ferreiro V, López Roldán PD, Padilla S, Calero Sierra I, Monzó García M, et al. Mental health impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2020 May 27;1-3. [ Links ]

10. Dosil Santamaría M, Ozamiz Etxebarria N, Redondo Rodríguez I, Jaureguizar Alboniga-Mayor J, Picaza Gorrotxategi M. Impacto psicológico de la COVID-19 en una muestra de profesionales sanitarios españoles Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment [Internet]. 2021 Abr-Jun [citado 12 Ene 2021];14(2):106-112. Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.rpsm.2020.05.004 [ Links ]

11. Erquicia J, et al. Impacto emocional de la pandemia de COVID-19 en los trabajadores sanitarios de uno de los focos de contagio más importantes de Europa. Med Clin [Internet]. 2020 Nov 27 [citado 14 Ene 2021];155(10):434-440. Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.medcli.2020.07.006 [ Links ]

12. Arnetz JE, Goetz CM, et al. Nurse Reports of Stressful Situations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Analysis of Survey Responses. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Nov [citado 14 Ene 2021];17(21):8126. Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph17218126 [ Links ]

13. Lozano Vargas A. Impacto de la epidemia del Coronavirus (COVID-19) en la salud mental del personal de salud y en la población general de China. Rev Neuropsiquiatr [Internet]. 2020 [citado 17 Ene 2021];83(1):51-56. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.20453/rnp.v83i1.3687 [ Links ]

14. Sampaio F, Sequeira C, Teixeira L. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on nurses' mental health: A prospective cohort study. Environ Res [Internet]. 2021 Mar [citado 20 Ene 2021];194:110620. Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.envres.2020.110620 [ Links ]

15. Tran BX, Ha GH, Nguyen LH, Vu GT, Hoang MT, Le HT, et al. Studies of Novel Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Global Analysis of Literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jun;17(11):4095. [ Links ]

16. García Iglesias JJ, Gómez Salgado J, Martín Pereira J, Fagundo Rivera J, Ayuso Murillo D, Martínez Riera JR, et al. Impacto del SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) en la salud mental de los profesionales sanitarios: una revisión sistemática. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2020 Jul 23;94:e202007088. [ Links ]

17. Danet Danet A. Impacto psicológico de la COVID-19 en profesionales sanitarios de primera línea en el ámbito occidental. Una revisión sistemática. Med Clin (Barc). 2021 May 7;156(9):449-458. [ Links ]

18. Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and erceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Jul;87:11-17. [ Links ]

19. Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Aug;290:113129. [ Links ]

20. Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D'Aniello GE, Stramba Badiale C, Pietrabissa G, Manna C, et al. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684. [ Links ]

21. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar;3(3):e203976. [ Links ]

22. Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory. En: Seisdedos N, editor. Manual del Inventario Burnout de Maslach. Síndrome del »,» ®,® §,§ ­, ¹,¹ ²,² ³,³ ß,ß Þ,Þ þ,þ ×,× Ú,Ú ú,ú Û,Û û,û Ù,Ù ù,ù ¨,¨ Ü,Ü ü,ü Ý,Ý ý,ý ¥,¥ ÿ,ÿ ¶,¶ quemado »,» ®,® §,§ ­, ¹,¹ ²,² ³,³ ß,ß Þ,Þ þ,þ ×,× Ú,Ú ú,ú Û,Û û,û Ù,Ù ù,ù ¨,¨ Ü,Ü ü,ü Ý,Ý ý,ý ¥,¥ ÿ,ÿ ¶,¶ por estrés laboral asistencial. Madrid: TEA;1997:5-28. [ Links ]

23. Elbay RY, Kurtulmus A, Arpacioglu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Aug;290:113130. [ Links ]

24. Kim SC, Quiban C, Sloan C, Montejano A. Predictors of poor mental health among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Open. 2021 Mar;8(2):900-907. [ Links ]

25. Zhu Z, et al. COVID-19 in Wuhan: immediate psychological impact on 5062 health workers. MedRxiv [Internet]. 2020 Mar [citado 24 Ene 2021];24:100443. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.20.20025338 [ Links ]

26. Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Jing M, Goh Y, Yeo LLL, et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Apr 6;M20-1083. [ Links ]

27. Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJH, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Aug;88:559-565. [ Links ]

28. Ortega Malla AL, Mesa Cano IC, Peña Cordero SJ, Ramírez Coronel AA. Miedo al coronavirus, ansiedad y depresión. Rev Uni Cienc y Tecnol. 2021 Jun;25(109):98-106. [ Links ]

29. Cipolotti L, Chan E, Murphy P, van Harskamp N. Factors contributing to the distress, concerns, and needs of UK Neuroscience health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Psychother. 2020 Jul 16;e12298. [ Links ]

30. Cuzco C, Carmona Delgado I, et al. Hacia una pandemia de salud mental. Enferm Intensiva [Internet]. 2021 [citado 30 Ene 2021];32(3):176-177. Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.enfi.2021.03.005 [ Links ]

Annex III: Independent variables related to depression, anxiety, stress, CE, PR and fear of COVID-19

Received: September 15, 2021; Accepted: January 03, 2022

texto em

texto em