Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Enfermería Global

versão On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 no.66 Murcia Abr. 2022 Epub 02-Maio-2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.478911

Originals

Knowledge, attitude, and practice of pregnant women before and after a group intervention

1 Universidad de Integración Internacional de la Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira . Redenção - Ceará - Brasil. gezebely@gmail.com

2 Universidad Estadual de Ceará . Brasil.

Introduction:

Given the doubts relevant to the pregnancy-puerperal period and the importance of the nurse as a health educator, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of a group educational intervention about the pregnancy-puerperal cycle on the knowledge, attitude, and practice of pregnant women.

Method:

An evaluative study on the knowledge, attitude, and practice with a quantitative approach was carried out with 20 pregnant women in 2019. An instrument was used before and after the educational intervention. Nine meetings were held, and 10 themes were addressed about the pregnancy-puerperal period. The data were analyzed using the Jamovi software.

Results:

The mean age of women was 26.2 years. An amount of 65% of pregnancies was not planned. There was a significant difference regarding the knowledge about the rights of pregnant women (p=0.023) and the importance of not giving water or tea to the baby (p=0.041). There was a change in the willingness to give birth in a 'lying down' position. There was also a difference in condom use after the intervention (p=0.008).

Conclusion:

Health professionals can use groups to promote the empowerment of pregnant women and enable them to seek high quality health care.

Keywords: Nursing; Obstetric Nursing; Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Health; Health Education; Health Promotion

INTRODUCTION

Health care quality during the pregnancy-puerperal period is a global challenge, as there must be adequate monitoring during this period to obtain comprehensive care for women1. However, the considerable changes that the pregnant woman undergoes, both bodily and physical, in most cases, are not approached during prenatal care2.

Prenatal care is essential to ensure the development of pregnancy, allowing a healthy delivery without impact on maternal health, including addressing psychosocial aspects and educational and preventive activities3.

In this scenario, the group approach to pregnant women emerges as a strategy to know their body and health status and favor their autonomy during pregnancy4. The participation of women and their partners in courses for pregnant women promotes the bond with health professionals, enabling the exchange of experiences, the promotion of self-care, information sharing, collective construction of knowledge, and the harmony between scientific and popular knowledge5.

This shared learning process between people with similar conditions encourages the exchange of experiences and knowledge, develops the feeling of altruism, and enables the creation of bonds and union between the participants6. Furthermore, it can promote adequate knowledge, attitudes, and health practices.

Nurses stand out in performing prenatal care in primary health care (PHC) facilities, carrying out educational activities for women and their families, individually or collectively, through groups for pregnant women3. Furthermore, the nurse can prepare the nursing care plan in the prenatal consultation, establishing interventions, guidelines, and referrals to other services7.

This study is justified by the need to clarify doubts relevant to the pregnancy-puerperal period and by the fact that the nurse is a health educator in PHC, working as a group facilitator that serves users, forming bonds, and promoting the valuation of health. Thus, the study's objective was to evaluate the impact of a group educational intervention about the pregnancy-puerperal cycle on the knowledge, attitude, and practice of pregnant women.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

This is a knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) evaluative study with a quantitative approach. The KAP methodology allows measuring the knowledge, attitude, and practice of a given population, leading to the diagnosis of these individuals, showing what people know, feel, and behave about a predefined topic8.

The study was carried out from February to November 2019 at the Reference Center for Social Assistance (RCSA) in the municipality of Redenção, CE. The population corresponded to pregnant women who assisted in the municipality's Family Health Strategies (FHS). The population consisted of 20 pregnant women assisted by the FHS and the RCSA. A non-probabilistic convenience sampling was used and considered the entire population, the 20 pregnant women who attended the institutions above.

The inclusion criteria were participating in the groups on the days set by RCSA and having a landline or cell phone number enabling contact after delivery, if necessary. The exclusion criterion was having a hearing or visual impairment or other limitation that prevented participating in the educational intervention or answering the evaluation form. The criterion for discontinuing was not attending at least six meetings.

The educational intervention consisted of health education workshops held in the auditorium of the RCSA of Redenção, CE. Ten themes were addressed: women's rights during pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium; understanding pregnancy; self-esteem and sexuality; the importance of prenatal care; nutrition of pregnant women and physical activity; labor and delivery; obstetric violence; care for the newborn; breastfeeding; and puerperium.

Nursing students and professors carried out the workshops. Audiovisual resources, group dynamics, conversation circles, dolls to simulate breastfeeding and care for the newborn, application of educational games, exploration of a serial album, and an educational folder on the themes mentioned above were used. Nine weekly meetings were held and averaged 1 hour and 30 minutes. Each group consisted of 10 women.

In the first meeting, the women were enrolled in the workshops, signed the informed consent form, and answered the pre-test questionnaire. The women who responded to the pre-test questionnaire comprised the sample of the educational intervention. For data collection, an instrument built by the researchers was used. It was composed of three parts: sociodemographic data, data on reproductive health, and the KAP survey about the pregnancy-puerperal cycle. In the last meeting, the application of the post-test was carried out with all participants.

The collected data were organized in Microsoft Office Excel 2016 and analyzed using Jamovi® software version 1.6.15. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were used. The McNemar test with continuity correction was used to verify the association between categorical variables. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

The project was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the University for International Integration of the Afro-Brazilian Lusophony via Plataforma Brasil and approved under protocol number 3,541,106.

RESULTS

The women had a mean age of 26.2 (SD: ±7.7) years, with a minimum age of 14.2 and a maximum age of 42.6. The average family income was 471 (SD:397) Brazilian reais. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic data of the participant women.

The women had an average weight of 67.5 (SD: 15.5) kilograms. The median number of pregnancies was 2, with a minimum value of 1 and a maximum of 8, and 1 delivery, with a maximum of 7. The average number of abortions was 0.45 (SD: 1.15), with a median of 0 and a maximum value of 5. The average of gestational weeks was 23.8 (SD: 6.8) weeks, with a median of 4 prenatal consultations. A percentage of 65% (n=13; 95%CI=43.3 - 81.9) of pregnancies was not planned and 90% (n=18; 95%CI= 69.9 - 97.2) reported that the pregnancy was wanted.

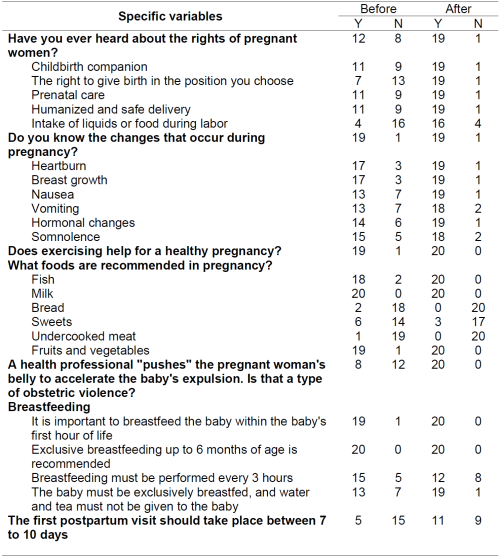

Table 2 shows the knowledge of pregnant women before and after participating in the educational intervention.

There was a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) concerning knowledge about the rights of pregnant women (p=0.023): the right to have a companion during birth (p=0.013); the right to choose the best position to give birth (p=0.001); the right to have prenatal care (p=0.013); the right to have a humanized and safe birth (p=0.013); and the right to eat or during labor (p=0.001). In addition, there was a difference in knowledge about the importance of not giving water or tea to the baby (p=0.041).

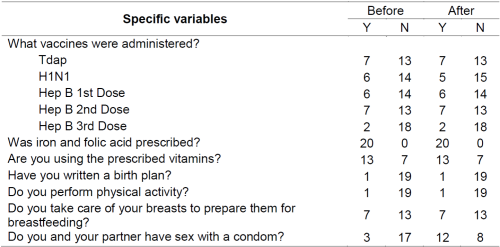

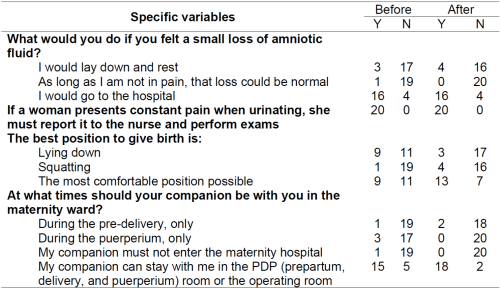

The attitudes of pregnant women before and after the educational intervention are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Attitudes of pregnant women before and after participating in the educational intervention.

There was no statistically significant difference regarding the participants' attitudes before and after the educational intervention.

Table 4 presents the women's practices before and after the intervention.

There was a statistically significant difference in the use of condoms in sexual practices after participating in the group of pregnant women (p=0.008).

DISCUSSION

Women had low family income, relating to social inequalities in Brazil from a macro-structural perspective. This dissimilarity is verified with the findings of a study carried out in Fortaleza, CE, where the family income of pregnant women ranged from no income to R$8,000.00, with a median of R$1,2009.

The economic aspect is emphasized since low average family income per capita has an inverse relationship with the fertility rate in adolescence10. In addition, the low maternal socioeconomic level increases the risk of maternal mortality in adolescents and preterm births11. In this context, implementing intersectoral mechanisms is encouraged to alleviate this adversity.

Concerning sexual and reproductive planning, more than half of pregnancies were not planned. A cross-sectional observational study found a percentage of 60.7% unplanned pregnancies9. It is understood that this fact results from the interaction of variables such as low income, low education, lack of employment, and low pay in the personal and family domains12.

It is highlighted that unintentional pregnancy represents a challenge for public health, as it contributes to maternal morbidity and mortality due to exposure to risks related to pregnancy, unsafe abortion, and childbirth13. The importance of health actions involving educational practices and family planning services is reinforced, especially in a vulnerable context14.

Concerning knowledge, the lack of information on pregnant women found in this study corroborates the harm of pregnant women caused by not knowing the benefits that their rights could provide and the opportunity to claim them15. This result may be related to health professionals' practices, such as the resistance to disseminate relevant information, pointing to the absence of mechanisms to disseminate pregnant women's rights16.

It is essential to value the relationships between pregnant women and other people to modify practices related to giving birth. Actions should emphasize providing information to the woman and her social support network members, enabling greater involvement15. For this purpose, the autonomy of the nurse is required, as this professional needs to know the information to offer to women17.

This study revealed that, before the educational intervention, most women were unaware that Kristeller's maneuver is a type of obstetric violence. In a qualitative study in which women described their pre-existing knowledge and experiences about Kristeller's maneuver, the interviewees felt uninformed and unable to refuse this maneuver because it was offered as a "little help" during birth18.

Pregnant women's knowledge about obstetric violence is crucial to the identification and prevention of such practices. Parturient women should also receive information on this issue during prenatal assistance. Therefore, social mobilization initiatives can contribute to expanding knowledge and dissemination about this problem and supporting the dissemination of good practices in delivery and birth19.

Concerning breastfeeding, women knew most items assessed. However, a portion of them expressed mistaken knowledge about giving water to the baby during exclusive breastfeeding. A study carried out in Porto Alegre (RS) revealed that, in the 30 days after delivery, 6.8% of children received water, 21.2% tea, and the introduction of breast milk substitutes was reported by 38.1% of the participants20.

Some factors interrupt exclusive breastfeeding, such as the belief of some nursing mothers in insufficient milk production, attachment difficulties, and various breast complications that can arise in the postpartum period associated with a lack of confidence and advice from family members and friends, as well as myths and beliefs related to baby cramps and causes of the baby crying20,21.

Concerning the participants' attitudes, when asked about possible signs and symptoms of the diagnosis for the onset of labor, most pregnant women reported that they would go immediately to the hospital when asked about the loss of amniotic fluid. This attitude reveals the mistake of some pregnant women when dealing with this situation, considering that the rupture of the amniotic membrane is not a defining factor for active labor and immediate referral to the hospital unit22.

The concern above is frequent among pregnant women, given the lack of information provided by professionals on existing criteria that define active labor22. In our study, there was no change in attitude towards this issue, reinforcing the need for the health professional to inform pregnant women about the alarm signs related to labor during prenatal consultations, preventing premature admission of these women in the hospital, and, consequently, unnecessary interventions.

Regarding the position to be adopted during labor, after completing this study, it was observed that the participants were willing to give birth in a position that ensured the greatest comfort for them. The change in this scenario reflects the positive influences that health education provides for pregnant women, especially concerning the demystification of some taboos and myths that remain present about the natural positions of women to give birth23.

As a consequence of the lack of educational actions, a study has reported the perception of postpartum women about the vertical position in childbirth. The study revealed that some women in primary care or even in maternity hospitals did not know the childbirth positions that could be adopted24. Thus, women must be informed during prenatal consultations and pregnant women's groups about the positions they can adopt during labor without any imposition by the health professionals.

Although most participants stated that the companion should be with them during prepartum, delivery, and immediate postpartum, a portion did not know about this right. This fact can interfere with the applicability of the companion law in the different contexts of pregnancy. A study pointed out that 57.5% of the interviewees did not know that there is a law that ensures their right to a companion, and 66.2% did not have the right to have a companion throughout the parturition process25. This highlights the need for greater investments in educational actions.

Most women did not carry out a birth plan with them. In this perspective, the literature points out that more studies are needed to identify the reasons for the low adherence to the birth plan and the creation of health policies that encourage the use of this instrument26. Challenges are pointed out for the use of the birth plan, such as the need for greater dissemination among professionals and pregnant women, adherence as a common practice in primary health care services, support for women in the development of this instrument, as well as the construction of plans that may change during the parturition process27.

It is essential to develop and implement actions in prenatal care that mobilize pregnant women to practice physical activity, as the data in this study showed that a few women performed physical activities although they knew that this is a factor related to a healthy pregnancy. The literature points out that the main barriers to non-adherence to physical activities during pregnancy are tiredness, not liking to exercise, busy schedule, taking care of children, fear, and lack of information about pregnancy28. Thus, it is necessary to promote programs that encourage pregnant women to practice physical activities and disseminate the benefits of physical activity for pregnant women and their fetuses29.

The use of condoms in sexual intercourse with a partner was encouraged during the educational interventional, later showing greater adherence by the participants. This behavior change is seen as information and clarification are provided, elucidating the harms of not using or inappropriately using this barrier contraceptive method. Resistance to condom use, especially in couples, becomes common as relationships become more sTable and trust increases30. However, the use of condoms at any stage of life for men and women, including during pregnancy, is highlighted, mainly due to the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections with the potential for vertical transmission.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings revealed that the educational intervention through a group strategy positively impacted pregnant women's knowledge, attitudes, and practices about the pregnancy-puerperal cycle. An improvement in knowledge about pregnant women's rights and the importance of not giving water and tea to the baby, and in the practice of using condoms during sexual intercourse were observed. This reinforces that educational interventions during pregnancy are essential and can contribute to the mother-child dyad's health and reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

As implications, this study raises the reflection on how educational activities in the prenatal care context are being carried out and the need to implement new strategies that favor the care of these clients. In this context, health professionals, especially nurses, can use groups to promote the empowerment of pregnant women and enable them to seek high quality health care through good obstetric practices recommended by the World Health Organization and the Ministry of Health.

The small sample size is one of the weaknesses of this study, as well as the non-random sampling method used and the use of a data collection instrument that has not been validated yet. Thus, future research employing randomization and control groups is required to evaluate the use of technologies at individual and collective levels to promote knowledge, attitudes, and appropriate practices in the pregnancy-puerperal period.

REFERENCIAS

1. Balsells MMD, Oliveira TMF, Bernardo EBR, Aquino PS, Damasceno AKC, Castro RCMB, et al. Avaliação do processo na assistência pré-natal de gestantes com risco habitual. Acta Paul Enferm [Internet]. 2018 [acesso em 16 mar 2021];31(3):247-54. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0103-21002018000300247&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

2. Teixeira GA, Costa FML, Mata MS, Carvalho JBL, Souza NL, Silva RAR. Fatores de risco para a mortalidade neonatal na primeira semana de vida. Rev Pesqui Univ Fed Estado Rio J Online [Internet]. 2016 [acesso em 11 mar 2021];4036-46. Disponível em: http://www.seer.unirio.br/index.php/cuidadofundamental/article/view/3943/pdf_1832 [ Links ]

3. Brasil. Atenção ao pré-natal de baixo risco [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2013 [acesso em 18 mar 2011]. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/atencao_pre_natal_baixo_risco.pdf [ Links ]

4. Dias EG, Anjos GB, Alves L, Pereira SN, Campos LM. Ações do enfermeiro no pré-natal e a importância atribuída pelas gestantes. Rev Sustinere [Internet]. 2018 [acesso em 31 mar 2021];6(1):52-62. Disponível em: https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/sustinere/article/view/31722 [ Links ]

5. Nunes GP, Negreira AS, Costa MG, Sena FG, Amorim CB, Kerber NPC. Grupo de gestantes como ferramenta de instrumentalização e potencialização do cuidado. Cid Em Ação Rev Ext E Cult [Internet]. 2017 [acesso em 16 mar 2021];1(1):77-90. Disponível em: https://www.revistas.udesc.br/index.php/cidadaniaemacao/article/view/10932 [ Links ]

6. Paiva MVS, Soares AMM, Lopes ARS, Santos KCB, Sardinha AHL, Rolim ILTP. Educação em saúde com gestantes e puérperas: um relato de experiência. Rev Recien - Rev Científica Enferm [Internet]. 2020 [acesso em 31 mar 2021];10(29):112-9. Disponível em: https://www.recien.com.br/index.php/Recien/article/view/dx.doi.org%2F10.24276%2Frrecien2358-3088.2020.10.29.112-119 [ Links ]

7. Gomes CBA, Dias RS, Silva WGB, Pacheco MAB, Sousa FGM, Loyola CMD. Prenatal nursing consultation: narratives of pregnant women and nurses. Texto Amp Contexto - Enferm [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 18 mar 2021];28. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0104-07072019000100320&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

8. Kaliyaperumal K. Guideline for conducting a knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) study. AECS Illum. 2004;4:7-9. [ Links ]

9. Gadelha IP, Diniz FF, Aquino PS, Silva DM, Balsells MMD, Pinheiro AKB. Determinantes sociais da saúde de gestantes acompanhadas no pré-natal de alto risco. Rev Rene Online [Internet]. 2020 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];42198-42198. Disponível em: http://periodicos.ufc.br/rene/article/view/42198 [ Links ]

10. Nascimento TLC, Teixeira CSS, Anjos MS, Menezes GMS, Costa MCN, Natividade MS. Fatores associados à variação espacial da gravidez na adolescência no Brasil, 2014: estudo ecológico de agregados espaciais. Epidemiol E Serviços Saúde [Internet]. 2021 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];30:e201953. Disponível em: https://www.scielosp.org/article/ress/2021.v30n1/e201953/ [ Links ]

11. Amjad S, MacDonald I, Chambers T, Osornio-Vargas A, Chandra S, Voaklander D, et al. Social determinants of health and adverse maternal and birth outcomes in adolescent pregnancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):88-99. [ Links ]

12. Ferreira HLOC, Barbosa DFF, Aragão VM, Oliveira TMF, Castro RCMB, Aquino PS, et al. Determinantes Sociais da Saúde e sua influência na escolha do método contraceptivo. Rev Bras Enferm [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 1 abr 2021];72(4):1044-51. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0034-71672019000401044&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

13. Yazdkhasti M, Pourreza A, Pirak A, Abdi F. Unintended Pregnancy and Its Adverse Social and Economic Consequences on Health System: A Narrative Review Article. Iran J Public Health [Internet]. 2015 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];44(1):12-21. Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4449999/ [ Links ]

14. Pedro CB, Casacio GDM, Zilly A, Ferreira H, Ferrari RAP, Silva RMM, et al. Fatores relacionados ao planejamento familiar em região de fronteira. Esc Anna Nery [Internet]. 2021 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];25(3). Disponível em: http://www.revenf.bvs.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1414-81452021000300209&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

15. Junqueira TL, Coelho ASF, Sousa MC, Louro N da S, Silva PS, Almeida NAM. Gestantes que recebem informações de profissionais de saúde conhecem seus direitos no período gravídico-puerperal. Enferm Foco Brasília [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 31 mar 2021];67-72. Disponível em: http://revista.cofen.gov.br/index.php/enfermagem/article/view/2213/607 [ Links ]

16. Gouveia GS, Lessa GM. Conhecimento da gestante e direitos assegurados pela rede cegonha: contribuição gestora. Rev Baiana Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];138-51. Disponível em: http://rbsp.sesab.ba.gov.br/index.php/rbsp/article/view/3221/2633 [ Links ]

17. Jardim MJA, Silva AA, Fonseca LMB. Contribuições do enfermeiro no pré-natal para a conquista do empoderamento da gestante. Rev Pesqui Cuid Fundam Online [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];432-40. Disponível em: http://www.seer.unirio.br/index.php/cuidadofundamental/article/view/6370/pdf_1 [ Links ]

18. Rubashkin N, Torres C, Escuriet R, Ruiz-Berdún MD. "Just a little help": A qualitative inquiry into the persistent use of uterine fundal pressure in the second stage of labor in Spain. Birth [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];46(3):517-22. Disponível em: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/birt.12424 [ Links ]

19. Lansky S, Souza KV, Peixoto ERM, Oliveira BJ, Diniz CSG, Vieira NF, et al. Violência obstétrica: influência da Exposição Sentidos do Nascer na vivência das gestantes. Ciênc Amp Saúde Coletiva [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];24(8):2811-24. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1413-81232019000802811&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

20. Gasparin VA, Strada JKR, Moraes BA, Betti T, Pitilin ÉB, Santo LCE. Factors associated with the maintenance of exclusive breastfeeding in the late postpartum. Rev Gaúcha Enferm [Internet]. 2020 [acesso em 15 mar 2021];41. Disponível em: http://www.revenf.bvs.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1983-14472020000100401&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=en [ Links ]

21. Moccelin JM, Schuster RV. Fatores que influenciam a interrupção precoce do aleitamento materno exclusivo: uma revisão integrativa. Rev Destaques Acadêmicos [Internet]. 2020 [acesso em 31 mar 2021];12(3). Disponível em: http://www.univates.br/revistas/index.php/destaques/article/view/2658 [ Links ]

22. Félix HCR, Corrêa CC, Matias TGC, Parreira BDM, Paschoini MC, Ruiz MT. The Signs of alert and Labor: knowledge among pregnant women. Rev Bras Saúde Materno Infant [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 18 mar 2021];19(2):335-41. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1519-38292019000200335&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en [ Links ]

23. Zirr OGM, Gregório OVRP, Lima OMM, Collaço OVS. Autonomia da mulher no trabalho de parto: contribuições de um grupo de gestantes. Rev Min Enferm [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 31 de março de 2021];23:1-7. Disponível em: https://www.reme.org.br/artigo/detalhes/1348 [ Links ]

24. Sousa JL, Silva IP, Gonçalves LRR, Nery IS, Gomes IS, Sousa LFC. Percepção de puérperas sobre a posição vertical no parto. Rev Baiana Enferm [Internet]. 2018 [acesso em 18 mar 2021];e27499-e27499. Disponível em: http://www.revenf.bvs.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2178-86502018000100353 [ Links ]

25. Santos ECP, Lima MR, Conceição LL, Tavares CS, Guimarães AM d'Ávila N. Conhecimento e aplicação do direiro do acompanhante na gestação e parto. Enferm Em Foco [Internet]. 2016 [acesso em 18 mar 2021];7(3/4):61-5. Disponível em: http://revista.cofen.gov.br/index.php/enfermagem/article/view/918 [ Links ]

26. Suárez-Cortés M, Armero-Barranco D, Canteras-Jordana M, Martínez-Roche ME. Uso e influência dos Planos de Parto e Nascimento no processo de parto humanizado. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2015 [acesso em 17 mar 2021];23(3):520-6. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0104-11692015000300520&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en [ Links ]

27. Medeiros RMK, Figueiredo G, Correa ÁCP, Barbieri M. Repercussions of using the birth plan in the parturition process. Rev Gaúcha Enferm [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 17 mar de 2021];40. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1983-14472019000100504&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

28. Alaglan AA, Almousa RF, Alomirini AA, Alabdularazaq ES, Alkheder RS, Alzaben KA, et al. Hábitos de atividade física das mulheres sauditas durante a gravidez. Womens Health [Internet]. 2020 [acesso em 16 mar 2021];16:1745506520952045. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506520952045 [ Links ]

29. Souza VA, Mussi RFF, Queiroz BM, Souza VA, Mussi RFF, Queiroz BM. Nível de atividade física de gestantes atendidas em unidades básicas de saúde de um município do nordeste brasileiro. Cad Saúde Coletiva [Internet]. 2019 [acesso em 1 abr 2021];27(2):131-7. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1414-462X2019000200131&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

30. Castro EL, Caldas TA, Morcillo AM, Pereira EMA, Velho PENF. O conhecimento e o ensino sobre doenças sexualmente transmissíveis entre universitários. Ciênc & Saúde Coletiva [Internet]. 2016 [acesso em 18 mar 2021];21(6):1975-84. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1413-81232016000601975&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Received: May 01, 2021; Accepted: December 18, 2021

texto em

texto em