My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Enfermería Global

On-line version ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.21 n.67 Murcia Jul. 2022 Epub Sep 19, 2022

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.507631

Originals

Beliefs and cultural practices of adolescent mothers in the care of their children under 5 years of age

1Faculty of Health Sciences, Corporación Universitaria Rafael Núñez. Cartagena, Colombia

2Universidad Metropolitana. Barranquilla, Colombia

Introduction:

When early childhood is given inadequate care, it can experience long-term damaging effects. In this sense, the cultural beliefs and practices of mothers are essential, especially when it comes to adolescents. The objective of this work was to know the beliefs and cultural practices of adolescent mothers in charge of taking care of their children under 5 years of age in a municipality of the Department of Bolívar (Colombia), during the second period of 2020.

Method:

Qualitative, phenomenological, and hermeneutical study, with 16 adolescent mothers of children under 5 years of age as key informants, to whom a semi-structured interview was applied until information saturation was reached, keeping the corresponding ethical and methodological rigor.

Results:

Beliefs about care were characterized because mothers think that it should be something integral, that it implies a lot of attention, and it helps to prevent disease. When taking care of their children, they experience feelings of affection, tenderness and gratitude to God. The teaching of the family is marked by myths, superstitions, and unfounded beliefs. The practices included breastfeeding and providing early complementary feeding. The relatives influenced the child's diet, especially mothers, grandmothers, and doctors.

Conclusion:

The cultural beliefs and practices of the adolescent mothers were shaped by favorable thoughts and feelings, with practices that favor the well-being of their children.

Keywords: (Source: DeCS) Beliefs; Culture; Knowledge; Attitudes and Practice in Health; Adolescent; child development; childcare; disease prevention

INTRODUCTION

Early childhood is perhaps the most critical period in the life of the human being, as important conFigurations take place as part of body and brain development1. This makes children highly sensitive to the social and physical world, and early life exposures (both harmful and beneficial) continue to perform the effects on health and well-being later in life2.

That is to say, the adaptability of children and the responsiveness of caregivers when it comes to meeting the needs of minors will be essential.

When children are deprived of adequate attention, such as stimulation, protection and nutritional care, the harmful effects can have long-term consequences for both families and communities. Is a matter of fact, children whose early development has been compromised, tend to have fewer personal and social skills and less ability to benefit from education, negatively impacting their future employability, earnings and well-being3. In Colombia, the parental and care practices that children receive in early childhood are “rooted in customs and integrated into the daily life of boys and girls”4, so it is necessary to provide evidence that takes into account the cultural component that sustains these actions.

In Cartagena, for example, the practices of protection against in-home risks tend to be between reasonable and good. It is worth mentioning that caregivers provide these children with age-appropriate toys and accompaniment when crossing the street. However, the situation is worrying in terms of practices such as putting a lid on latrines and toilets and moving them away during celebrations in which gunpowder is used5,6.

When the caregivers of children in early childhood are their mothers and they are going through adolescence, the situation becomes especially relevant. Indeed, “facing the birth of their children, adolescents are faced with assuming a maternal role for which they were generally not prepared, which implies changes in habits that are typical of the stage of the life cycle they are experiencing, as well as having to create or recreate parenting practices with which the development of the child should be guided”7.

The lack of maturity in adolescents and the persistence of fears and anguish in their maternal role - experienced as anguish in the face of the possibility of the child gets ill, and the frequent questioning of their own personal resources that ensure the physical and emotional care of their child8, are common situations among mothers in this stage, however, are perceived as serious scenarios when the Figures and trends of pregnancy at an early age are explored. Hence, this research sought to know: What are the beliefs and cultural practices of adolescent mothers in the care of their children under 5 years of age in a municipality in the Department of Bolívar during the second period of 2020?

METHOD

A qualitative9phenomenological10and hermeneutical study was carried out11. The population was constituted by adolescent mothers of children under 5 years of age who reside in a municipality in the Department of Bolívar. The sample was determined by information saturation12, considering the following inclusion criteria: adolescent mothers aged between 10 and 19 years, with children under 5 years of age, residents of the study center municipality and availability to participate voluntarily.

As a data collection technique, the semi-structured interview was used, which was designed by the research team taking into account the literature review. The script of the interview was submitted to evaluation by expert peers prior to the process of immersion in the field. The interview had 2 main dimensions, in correspondence with the objectives of the research:

Beliefs of adolescent mothers regarding the care of their children under 5 years of age.

Care practices of mothers with their children under 5 years of age. During the information collection process, the interviews were recorded and transcribed in a period of time not exceeding one month, and the analysis process was carried out based on a data ordering matrix in Microsoft Excel, to extract the subcategories that responded to the defined dimensions.

As an ethical measurement, the aspects issued in the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical principles established in Law 911 of 2004 were preserved, under which the autonomy of the participants was guaranteed through the use of consent and informed assent, the principle of beneficence, truthfulness and confidentiality.

On the other hand, this research was endorsed by the research committee of the Nursing Program, and was classified as risk-free research, as established by Resolution 8430 of 1993.

RESULTS

In this section of the document, the findings obtained after the process of collecting, capturing, processing and analyzing the information collected from the interviews with the participating adolescent mothers are disclosed.

The presentation of the results begins with the treatment of the sociodemographic aspects of the participants; this was done to identify its main characteristics, which served as a preamble to the following sections.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of adolescent mothers

Source: Data collection instrument, 2021

Of the 16 participants interviewed, it was found that 62.5% were between 15 and 17 years old, 56.3% had incomplete secondary school, 87.5% were of rural origin, 93.8% live in level 1, 50% are single mothers, 75% were housewives, 93.8% have income equal to 1 minimum wage, 100% have subsidized social security, 56.3% had at least 1 birth, 31.3% said they had had 1 abortion. Finally, 37.5% had their first pregnancy at 15 years old, 25% at 14 years old, 35% at 16 years old and 2.5% at 17 years old.

During the analysis process, the categories and subcategories emerged that allowed explaining each of the previously defined dimensions.

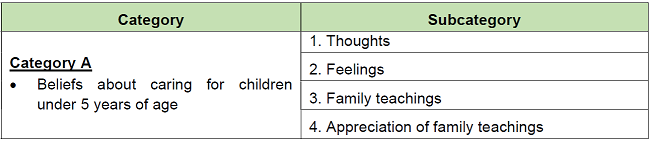

Category A: Beliefs about caring for children under 5 years of age

Subcategory 1: Thoughts

Adolescent mothers think that care is something comprehensive that implies a lot of attention, to the extent that it constitutes a broad set of procedures, tasks and activities that, when put into practice, have the purpose of ensuring the well-being and life of their children.

“Con los niños menores de cinco años se tiene que tener mucho cuidado porque ellos no dependen de ellos mismos, hay que estar pendiente de la atención de ellos, cómo alimentarlos, cómo llevar la cuchara a la boca, cómo peinarse, …” (voice CPC).

“El cuidado que deben tener los niños menores de 5 años es todo el cuidado del mundo. Primero porque son niños muy pequeños, no se saben cuidar ellos mismos; no miden el peligro…” (voice RCP).

Subcategory 2: Feelings

Most of the participants expressed that the most recurring feeling is love, in some cases completed with affection, as indicated by the following voices:

“Se experimenta mucho amor, cariño y, cuando uno experimenta eso con el niño, eso es lo que él va a reflejar” (voice MCC).

“Para mí… Yo siento amor y cariño por mi hija” (voice EGR).

“Siento amor, cariño…” (voice YOM).

“Un sentimiento muy grande. Amor, cariño” (voice KG).

While in other cases loveis presented in connection with tenderness, there was gratitude towards God, and mixed feelings.

Subcategory 3: Family teachings

Diversity of teachings was found. Some were threats from the environment, mainly due to the risk of getting sick. This was extracted from two opinions of the participants:

“No serenarlos. No sacarlos a la calle para que no se enfermen. Arroparlos bien, ponerles su gorro, sacarles los gases” (voice YOM).

“No serenarlos, mantener un buen cuidado con ellos. Hilo en la frente cuando tienen hipo, el gorrito para cuidarle la mollerita. No salir antes de los 40 días” (voice LHS).

Teenage mothers have also been taught in their family that children should receive care around accident prevention:

“Mi abuela y mi madre me han enseñado que a los niños menores de cinco años debemos cuidarlos. No podemos dejarlos solos. Por lo menos cuidarlos porque a esa edad, experimentan muchas cosas…” (voice ODV).

Subcategory 4: Appreciation of family teachings

All the participants confirmed that they agree with these recommendations from their family, since they have confirmed these teachings, as a result of putting them into practice during the act of caring. This can be seen in the following speeches:

“Sí, tienen mucha razón[la madre, la abuela, etc.] porque lo he comprobado” (voice KDLR).

“Bueno, yo creo que sí, mi madre y mi abuela tienen razón, porque lo que ellas me han dicho es verdad… Así como ellos me han dicho es cierto” (voice ODV).

Similarly, to what was described, other adolescent mothers agreed that the teachings of their relatives are true, to the extent that they come from the experience of their mothers and grandmothers.

“Bueno, sí[son ciertas] porque ellas fueron las que me criaron y, gracias a Dios, yo tengo salud, y yo he crecido llena de salud” (voice MCO).

“Claro que sí, porque si no cojo concejos como creo que como madre primeriza voy a atender al niño si no cojo concejos de una persona mayor (voice EGR).

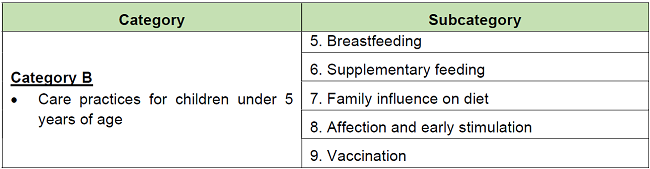

Category B: Care practices for children under 5 years of age

Subcategory 5: Breastfeeding

It was found that the infant had been breastfed. In contrast, only two mothers indicated that they had not breastfed their child.

“Solamente le di leche hasta los 2 meses, le di a esa edad porque no me agarraba el seno, entonces sentía que no se llenaba con el seno, yo le daba tetero” (voice DZP).

Regarding exclusive breastfeeding, it was noteworthy that a mother said that she neverprovided it to her son, arguing that she had a health condition that made it impossible for her to do so, however, she also presented misconceptions about this practice.

“Yo nunca di teta porque yo fui operada de mis senos… Y no pude dar seno. Además, la leche no es lo único que sostiene a un pelao. A un pelao uno le da leche de ganado, agüita de arroz tostado, le da su sopita licuadita” (voice YCH).

Meanwhile, other interviewees expressed remarkably short times, less than six months, during which they fed their children exclusively with breastfeeding. Others expressed their refusal to give exclusive breastfeeding, and even argued that the child was not satisfiedand they wanted the child to gain weight.

“Hasta los 4 meses le di solamente leche porque yo lo veía bajito de peso y quería que estuviera gordito” (voice EOO).

Subcategory 6: Supplementary feeding

The adolescent mother who gave her son complementary food earlier (from 1 month) argued medical reasonsfor doing so, as well:

“Al mes le di otros alimentos. Una vez suspendido el seno, por lo de la mastitis le empecé la alimentación complementaria. Ya le daba el agua, que si el puré de papa, las sopitas, que si arroz…” (voice ODV).

Other mothers indicated that at 2 and 4 months of age they gave him foods such as porridge and soups.

Subcategory 7: Family influence on diet

Grandmothers and mothers were recognized as a source of information, regardless of whether what was indicated was adequate or not:

“Sí, mi mamá, porque me decía que el niño estaba en una edad que tenía que comer la papilla, la sopita de verdura” (voice MCC).

“Sí, sí… mi mamá me decía” (voice LMS).

Subcategory 8: Affection and early stimulation

There were two ideas that could be extracted in relation to the affection and early stimulation that children under 5 years of age should receive. On the one hand, some mothers described these practices as important, arguing that they determine, in the future, the behaviors and mental health status of their children:

“…Es algo muy importante” (voice ODV).

“Bueno…… que es importante para su desarrollo emocional y social” (voice DZP).

“Es muy importante dedicarles afecto, para que sean amoroso y[así,] lo ayudamos en su crecimiento (voice EOO).

On the other hand, there were the mothers who valued emotional care practices as necessary.

“Hay que darles mucho amor para que se sientan muy bien, para prevenirles enfermedades y virus” (voice LMS).

“Desde que ellos nacen hay que darles cariño, amor, de todo” (voice KDLR).

Subcategory 9: Vaccination

Regarding the practice of vaccination, it was found that, in its entirety, the mothers agreed that vaccination is useful for the prevention of diseases.

“Sí[es importante], porque eso previene varias enfermedades” (voice LHS).

“Claro porque los cuida a nivel de salud, los mantiene sanos, protegidos” (voice DZP).

“Sí, porque lo ayudamos a prevenir enfermedades” (voice EOO).

Within the analysis other subcategories emerged such as: Clean environment, Hand washing, and Health care for disease prevention, which are part of the care practices that mothers carry out with their children under 5 years of age.

DISCUSSION

The present study consisted of an analysis of the beliefs and care practices carried out by adolescent mothers of children under 5 years of age. Starting from the premise expressed by Srivastava13, according to which in early childhood the human being experiences the most important stage of his physical and cognitive development, which is conditioned to the genetic endowment he possesses, but also to the environmental conditions. All this, when intertwined, determine the achievement of the maximum development potential. It is for these reasons that health care practices, nutrition, early stimulation, protection, among others, are fundamental requirements for optimal growth and development, both in the present and in the future.

To undertake this research, a sociodemographic characterization was first carried out, in which it was found that the participating adolescent mothers were between 12 and 17 years old, with complete and incomplete primary and secondary education, born in rural contexts, low socioeconomic levels, some of them were single, and others in free marital union. Additionally, it was found that all belonged to the subsidized health regime, most worked as housewives and lived in low-income households.

When comparisons were made with other studies, differences were detected in respect to Cherrez14, who reveals that their participants were mainly 19 years old (36.37%), but similarities in respect to living in free marital union (90.91%), and have completed secondary education (51.52%). There was greater similarity with the contribution of Franco et al.15who reveal the presence of adolescents with an average age of 16.8 years, in a free marital union (46.7%), and with a low level of schooling.

In regards to the educational aspect, it should be pointed out that when pregnancies occur at an early age, they generally affect school continuity. The investigation carried out by Samano et al.16reveal that school dropout is common among this population, and it is revealed that adolescents become more likely to work or -as this research found- to be a housewife or simply to rest at home. This contrasts with the perspective of authors such as Lawan et al.17who state that education passively affects women's confidence and is associated with greater awareness of their own health and that of their young children. However, this must be materialized by the fact that baby care practices are dictated by social norms and cultural values transmitted from generation to generation, and are not always based on reliable evidence.

The analysis of beliefs about the care of children under 5 years of age allowed us to understand that mothers present a series of favorable thoughts and feelings, which show that the bond forged between mother and child is very strong. Indeed, they value the care of their baby as something integral, which implies a lot of attention and dedication on the part of the mother, in this context, they experience a lot of love, affection, tenderness and gratitude with God. When comparing with the contribution of Hollowell et al.18it was found that about 90% of mothers with a child under 1 year old reported that they never left the child with another person when they went out during the day, that is, they considered care to be their entire responsibility.

In addition, similarities were found with the perspective of Ceka and Murati19, whose study showed that the mother has a very important role in the care of children under 5 years of age. Its most important functions are related to the defense of the child, and its integral development. The protection of the mother includes various types of actions, such as physical care, psychological protection, emotional security, health and hygiene conditions, and a safe home environment.

In general, beliefs in terms of thoughts and feelings can be understood according to the arguments expressed by Al-Bkerat20, in the sense that culture is the element from which they emerge, consolidate and socialize. All this knowledge, meanings and ways of understanding the world are transmitted from generation to generation, through group and individual effort. This coincided with what was revealed by the adolescents participating, who affirmed that their mothers and grandmothers are the ones who transmit this knowledge to them.

It was observed that family members teach adolescent mothers how to take care of their children in the face of environmental threats, accident prevention and nutrition, but all this is marked and mainstreamed by myths, superstitions and unfounded beliefs. This agrees with what was revealed by Lawan et al.17insofar as the knowledge that is transmitted from generation to generation preserves a cultural substratum supported by ways of understanding the world, not necessarily supported by scientific knowledge.

It was found that the mothers believed that the teachings that have been transmitted to them by their relatives are real because, in their opinions, the experience confirms them. This can be conceived under the approaches of Kankaanpää et al.21according to which the idea of adequate care, although it depends on the context, takes place in everyday life, in the same way, caregivers understand the Figure of authority exercised by older people, especially those female members of the family.

When exposing the care practices, it was known that the participants took into account different aspects of feeding, such as incomplete breastfeeding and complementary feeding. All this in connection with previously identified beliefs. Some mothers argued that they did not exclusively breastfeed because their health condition made it impossible. In most cases, this type of breastfeeding ended before 6 months, which was mainly due to the presence of misconceptions about this practice, such as that the child was not satisfied or that it was necessary for the child to gain weight. In this sense, the mixed feeding was presented before the generally recommended time (6 months).

Comparisons with other studies revealed the existence of similarities, as was the case with the work of Lawan et al. 17where all the mothers reported that they gave some form of mixed feeding to their babies before 6 months of age and the most common was to give water to the child in the desire for the child to gain weight. In regards of this subject, mothers usually think that the Figure of the child with a certain overweight is desirable. This was explained based on what was referred by Al-Bkerat20in relation to the fact that cultural beliefs can influence the perceptions of parents about the health status and behaviors of their children, therefore, according to Ocampo and Salazar22, parents may have different perceptions of what is considered a healthy child, thus perceiving that thinness is a reflection of poor health and malnutrition.

There were similarities with the findings and arguments of Kavle et al.23while the early introduction of food may originate in the mother's inability to breastfeed, due to fatigue or hunger as a result of the energy expended during the act of lactating -especially if you are a teenage mother-. Consequently, the times when the child shows signs of dissatisfaction with breast milk must be added, for example, crying, reaching for other foods, or refusing to breastfeed.

Female members of the families had an influence on the practices of the adolescent mother regarding the feeding of her baby. Basically, mothers and grandmothers, although there were only two cases in which the influence of doctors was recognized. This situation clearly has its origin in the immaturity and lack of experience of adolescent mothers to care for their child. This is recognized by Hollowell et al.18who detect that grandmothers play an increasingly important role in the care of babies. Kavle et al.23also express that mothers, fathers and grandmothers influence care practices, emphasizing the importance of breastfeeding. But they also often sow incorrect beliefs that become problematic practices, as pointed out by Cooper et al. 24who state that many mothers, fathers and grandmothers express the opinion that women do not have enough breast milk to satisfy the child's hunger.

Among the participants, coherence was evidenced concerning early stimulation, providing love and affection to the infant, it was necessary and important because it will determine their behaviors and mental health in the future. This clearly coincides with what was expressed by Hollowell et al.18about the fact that effective interaction, stimulation and responsive care during a child's first years play a key role in the development of the brain that favors cognition, motor skills and neurological development. At this time, suboptimal parental interactions and poor nutrition can have detrimental long-term effects on health, educational performance, and economic prosperity. Likewise, from the perspective of Ceka and Murati19when every child is properly cared for and educated by the mother, he is expected to achieve adequate physical, mental and social development.

Therefore, early stimulation is crucial since at birth, babies experience many forms of tactile interactions with their parents and secondary caregivers as members of the family, as reported by Whitters25. Thus, since their senses are primed to learn, lifelong emotional bonds with family members can be quickly established. Hollowell et al.18emphasize that parent-centered care practices that promote nurturing can improve child development outcomes and offset developmental delays due to risks such as poverty and malnutrition.

As for vaccination, the interviewed mothers underlined that it is a practice that they consider fundamental in the care of their children that helps with prevention of diseases. This differs from what was revealed the investigation by Bağli y Küçükoğluc26, where the proportion of mothers who reject vaccines is high, thinking that they are harmful and do not trust on it. This is consistent with what was stated by Bianco et al.27whose findings revealed that at least a quarter of the mothers reported to have refused or delayed at least one dose of vaccine for their child. In addition, they explained that this was worrying because it increases the propensity to contract vaccine-prevenTable diseases.

In accordance with the practices described, handwashing was also classified as important because children often touch dirty objects and put their hands in their mouths, added to the fact that it is a fundamental measure within the current context of the pandemic by coronavirus. These positive practices are opposed to what was described by Opara et al.28who assert that handwashing with soap and water is rare in low-income countries.

The practices that framework health care for disease prevention, expressed by adolescent mothers, were varied and suggested by family members in most cases. This differs from what it was explained by Park et al.29who affirm that neglect and lack of hygiene resources were the most commonly referred barriers to not carrying out care practices, which is interconnected at the same time with socioeconomic level and mothers' education.

This study had some limitations, one of them was the accessibility to the population of interest due to the fact that the field work was carried out in a rural and dispersed area, an aspect that altered the times and, therefore, the schedule. It is recommended that future studies establish recruitment and effective recruitment strategies in order to reduce participation bias.

On the other hand, it is important to highlight that the findings presented here were analyzed from an interpretive and subjective perspective, therefore, it is suggested that these results be contrasted or compared with studies of a quantitative nature in order to obtain a more comprehensive overview of the phenomenon of beliefs and care practices in this population group.

Muñoz and Pardo30, affirm that the care practices of adolescent mothers begin during pregnancy and continue during their upbringing, and that these in turn are rooted in their beliefs, myths and cultural values inherited from generation to generation, which shows patterns of cultural care. Taking the above into account, it is recommended that future research studies consider the emerging cross-cultural approach that significantly influences rural populations.

CONCLUSION

This study found out that the cultural beliefs that adolescent mothers have regarding the care of their children under 5 years of age were varied. As part of the identified subjectivities, a series of thoughts and feelings were distinguished that suggest that care is understood as something integral, that implies a lot of attention, that allows the prevention of diseases and that, by definition, is their responsibility. With reference to practices, it was concluded that breastfeeding was frequent, however, it was rare that it took place exclusively according to the minimum time recommended by international organizations, given that complementary feeding was introduced early, as well as the influence of family and doctors.

Thanks

To the group of nursing students from the Nursing Program, Camila Altamiranda Agámez, Eduar José Martínez Hernández, Yuranni Ortiz Arias and Yesenia Urquijo Alvarado, for their valuable contribution in collecting information.

REFERENCES

1. Heo J, Krishna A, Perkins J, Lee H, Lee J, Subramanian S, Juhwan J. Community Determinants of Physical Growth and Cognitive Development among Indian Children in Early Childhood: A Multivariate Multilevel AnalysisInt. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17(1): 1-12. [ Links ]

2. Boyce W, Hertzman C. Early Childhood Health and the Life Course: The State of the Science and Proposed Research Priorities. En: Neal Halfon ChristopherB. Forrest Richard M. Lerner Elaine M. Faustman. Handbook of Life Course Health Development. Springer: Cham, Switzerland; 2018. p. 61-93. [ Links ]

3. Richter L, Black M, Britto P, Daelmans B, Desmond C, Devercelli A, Dua T, Fink G, Heymann J, Lombardi J, Lu C, Naicker S, Vargas E. Early childhood development: an imperative for action and measurement at scale. BMJ Glob Health. 2019; 4: 154 - 160. [ Links ]

4. Varela S, Chinchilla T, Murad V. Prácticas de crianza en niños y niñas menores de seis años en Colombia. Revista del Instituto de Estudios en Educación Universidad del Norte. 2015; 22: 193-215. [ Links ]

5. Cárdenas K, Hurtado Y, Mendoza M, Payares S. Prácticas para la prevención de accidentes en el hogar en cuidadores de niños de 1 a 5 años, del barrio el Pozón. Cartagena 2017. Cartagena: CURN; 2018. [ Links ]

6. Barrios J, Cañón Y, Ortiz J, Ramírez D. Conocimientos y prácticas sobre lactancia materna en madres adolescentes en un barrio de la localidad 2 de Cartagena de Indias, 2018. Cartagena: CURN; 2018. [ Links ]

7. Henao N, Villa M. Promoción del desarrollo como práctica de crianza de las madres adolescentes. Revista Eleuthera. 2018; 18: 74-91. [ Links ]

8. Botero L, Giraldo M, Zuluaga C. Maternidad en adolescentes y su relación con las experiencias vinculares tempranas. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte. 2018; (54): 114-128. [ Links ]

9. Sampieri H, Collado C, Baptista P. Metodología de la investigación. 4 ed. México D.F.: McGraw-Hill; 2016. [ Links ]

10. Trejo F. Fenomenología como método de investigación: Una opción para el profesional de enfermería. Enfermería Neurológica. 2017; 11(2): 98-101. [ Links ]

11. Ángel D. La hermenéutica y los métodos de investigación en ciencias sociales. Estud. Filos. 2016; (44): 9-37. [ Links ]

12. Martínez C. El muestreo en investigación cualitativa. Principios básicos y algunas controversias. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2015; 17(3): 613-619. [ Links ]

13. Srivastava R. Early Childhood Care and Education. Indian Pediatrics. 2020; 57: 793-794. [ Links ]

14. Cherrez L. Factores que predisponen al embarazo precoz y grado de satisfacción sobre el control prenatal en las gestantes adolescentes atendidas en el Establecimiento de Salud I - 4 Consuelo De Velasco - Piura año 2016. Piura: Universidad Católica Los Ángeles Chimbote; 2017. [ Links ]

15. Franco J, Cabrera C, Zárate G, Franco S, Covarrubias M, Zavala M. Representaciones sociales de adolescentes mexicanas embarazadas sobre el puerperio, la lactancia y los cuidados del recién nacido. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2018; 75: 153-159. [ Links ]

16. Sámano R, Martínez H, Robichaux D, Rodríguez A, Sánchez B, Hoyuela M, Godínez E, Segovia S. Family context and individual situation of teens before, during and after pregnancy in Mexico City. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017; 17(382): 1-16. [ Links ]

17. Lawan UM, Adamu AL, Envuladu EA, Akparibo R, Abdullahi RS. Does maternal education impact infant and child care practices in African setting? The case of Northern Nigeria. Sahel Med J. 2017; 20: 109-116. [ Links ]

18. Hollowell J, Belem M, Swigart T, Murray J, Hillc Z. Age-related patterns of early childhood development practices amongst rural families in Burkina Faso: findings from a nationwide survey of mothers of children aged 0-3 years. Glob Health Action. 2020; 13(1): 1772560. [ Links ]

19. Ceka A, Murati R. The Role of Parents in the Education of Children. Journal of Education and Practice. 2016; 7(5): 61-64. [ Links ]

20. Al-Bkerat M. Nutritional beliefs and practices of arabic speaking middle Eastern mothers. Open Access Dissertations. Rhode Island: University of Rhode Island; 2019. [ Links ]

21. Kankaanpää S, Isosävi S, Diab S, Qouta S, Punamäki R. Trauma and Parenting Beliefs: Exploring the Ethnotheories and Socialization Goals of Palestinian Mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2020; 29: 2130-2145. [ Links ]

22. Ocampo Y, Salazar LT. Percepción de los padres o cuidadores de niños con riesgo de sobrepeso, sobrepeso y obesidad, y los antecedentes familiares y estilos de vida. [trabajo de grado]. Rionegro (Medellín): Universidad Católica de Oriente; 2020. [ Links ]

23. Kavle J, Pacqué M, Dalglish S, Mbombeshayi E, Anzolo J, Mirindi J, Tosha M, Safari O, Gibson L, Straubinger S, Bachunguye R. Strengthening nutrition services within integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illnesses in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Evidence to guide implementation. Matern Child Nutr. 2019; 15(Suppl 1): e12725. [ Links ]

24. Cooper C, Kavle J, Nyoni J, Drake M, Lemwayi R, Mabuga L, Pfitzer L. Perspectives on maternal, infant, and young child nutrition and family planning: Considerations for rollout of integrated services in Mara and Kagera, Tanzania. Matern Child Nutr. 2019; 15 (Suppl 1): e12735. [ Links ]

25. Whitters H. Let love liberate our children to learn. Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care. 2020; 19: 1-9. [ Links ]

26. Bagli E, Küçükoglu S. Determination of Knowledge, Thought and Attitudes of Mothers for Childhood Immunization. Rumi Pediatric Conference: Konya; 2019. [ Links ]

27. Bianco A, Mascaro V, Zucco R, Pavia M. Parent perspectives on childhood vaccination: How to deal with vaccine hesitancy and refusal? Vaccine. 2019; 37: 984-990. [ Links ]

28. Opara P, Alex-Hart B, Okari T. Hand-washing practices amongst mothers of under-5 children in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2017 Feb;37(1):52-55. [ Links ]

29. Park J, Mwananyanda L, Servidone M, Sichone J, Coffin S, Hamer D. Hygiene practices of mothers of hospitalized neonates at a tertiary care neonatal intensive care unit in Zambia. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development. 2019. 1-9. [ Links ]

30. Muñoz-Henríquez M, Pardo-Torres MP. Significado de las prácticas de cuidado cultural en gestantes adolescentes de Barranquilla. Aquichan. 2016;16(1): 43-55. [ Links ]

Received: January 15, 2022; Accepted: February 19, 2022

text in

text in