Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Enfermería Global

versión On-line ISSN 1695-6141

Enferm. glob. vol.23 no.73 Murcia ene. 2024 Epub 23-Feb-2024

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.574951

Reviews

Current status and trends in the training process of critical care nurses

1Nurse. Professor at the Faculty of Health Sciences. Marian University. Pasto, Nariño. Colombia

Introduction:

International Organizations recognize that, for the health professions, the development of their specialties is transcendental since it allows them to deepen knowledge and skills for a more qualified professional practice that allows improving the quality of care.

Objective:

To explore the state of the art, application of nursing models and theories in intensive care units and trends in the training of nursing specialists for critically ill patients.

Method:

Documentary research whose object of study were 17 research articles related to the subject, the articles were captured in international databases Scielo, Elsevier, ScienceDirect, published between 2011-2021. A matrix for the selection of investigations and the Investigation Analytical Sheet were used as information collection instruments. The analysis was oriented based on the evolution of the training process, theoretical-disciplinary approaches and training trends and challenges

Results:

Articles from documentary reviews were found and, to a lesser extent, from qualitative or quantitative research studies.

Conclusions:

The study allowed us to recognize the progress of the training process and the evolution of teaching-learning strategies typical of traditional educational models to others that stimulate reflective and critical thinking. The literature that accounts for the application of nursing models and theories in critical care units is scarce; novel perspectives related to nursing training for critical care were found.

Keywords: advanced practice nursing; nursing education; critical care; trends; thought. Dec's Bireme

INTRODUCTION

Intensive care has expanded and continues to grow every day, not only in terms of technology but also in terms of optimizing, training, and updating the skills of professionals who provide it.

Nursing specialties have been identified worldwide since the emergence of public health nursing specialties in the early 20th century. Since then, they have grown rapidly owing to health needs and demands, new knowledge, technological advances, and the advancement of the profession.

International organizations and health systems recognize that the development of specialties is critical for health professions because it allows them to deepen and broaden their knowledge and skills, leading to a more qualified professional practice that improves health care quality. This has been recognized in various countries, and some of them have chosen to ensure quality by creating specialties in emergency care, emergency medicine, and intensive care according to the characteristics of their environments (1). The number of specialties varies by country, ranging from a few (6-8 specialties) to more than 50, as is the case of the United Kingdom. Since 1983, all countries have recognized the urgent need for qualified nurses to be prepared beyond their basic training (1).

Nursing specialization in the care of critically ill patients is a relatively new and young discipline that aims to deepen this specific area of knowledge. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated both a need for training in this field and a scarcity of nurses specializing in this area, making accelerated training in this area necessary. Nursing professionals specializing in the care of critically ill patients are an essential health resource that provides coverage for the high frequency of cardiovascular processes, trauma, and the high demand for urgent care.This evolution has been marked by a significant technological advancement and a great improvement in effectiveness, with the achievement of significant challenges in the rapid care of critically ill patients(2).

According to data on the number of nursing specialization graduates in Colombia between 2001 and 2017, one of the most requested areas of knowledge is critical care (1,571 graduates), followed by emergency (626) and oncology care (218)(3).

Training processes in this specialization have changed and evolved as knowledge has advanced. Around 1860, Florence Nightingale, the first nurse, established the Nightingale Training and Home School for Nurses at St. Thomas's Hospital in London with 10 students (4). The school was founded on two principles: first, nurses should gain practical experience in hospitals that are specially designed for that purpose; second, nurses should live in a suiTable home in order to lead a disciplined life(5,6). Over time, this vision evolved to focus on issues that reinforced the profession and discipline. After World War II, traditional education focused on lectures gave way to problem-based education(7). Teaching is no longer centered on the teacher but on the student, who bears the learning responsibility. In this regard, McMaster University in Canada was a pioneer in student-centered learning. The emphasis of this model remained on the acquisition of scientific knowledge, with new principles incorporated to facilitate it(7).

The Bologna process initiated the educational transformation and the obligation to direct education toward the attainment of competencies(8), therefore, universities for both undergraduate and graduate studies focused on the fact that the healthcare professional must acquire competencies in knowledge, skills, and attitudes during his/her training. In this sense.

Even before the pandemic, the global society demanded changes in the higher education teaching-learning systems in response to the changing scenarios caused by the fourth industrial revolution and in response to a society with greater access to information through digital technologies. The pandemic demonstrated that there are numerous ways to learn, particularly when using digital technologies. However, it is clear that the use of these modern technologies entails new challenges that cannot be avoided in higher education. Technologies such as virtual reality (VR) can enrich educational environments by enabling the visualization of complex structures and providing timely assessment and feedback(9)providing many benefits to learning(10).

The present study was carried out in order to explore the state of the art in the training process of nursing professionals in the specialization for the care of critically ill patients and obtain relevant data about theoretical-disciplinary approaches and identify trends and/or or challenges in the training process

METHODOLOGY

This state-of-the-art of nursing education is framed within the research typology “documentary review,” and it aims to recover and transcend the accumulated knowledge within a specific area. The study was developed in the following phases(11)

- Topic identification and selection of the guiding question: How has the specialization training process evolved, what are the approaches, what are the trends and challenges in the training process?

- Establishing study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria:

- Complete articles between the years 2011-2021.

- Articles that present in the title or abstract of the publication one or more of the keywords: State of the art; trends; academic training; professional competence; Nursing; critical care specialization; advanced practice nursing; intensive nursing; intensive care critical care; advanced care.

Exclusion criteria:

After the selection of articles, a complete reading of the article was carried out and then a selective reading of the bibliographic material using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Analytical reading was carried out in the selected texts, and for this purpose, the sheet for each article was prepared in summary form. The file included: title of the article, name of the journal, year of publication, methodology used, results.

In this way, 21 articles were found, of which 18 were chosen, which met the inclusion criteria and served as a source of consultation. The data were selected and subsequently coded and interpreted

RESULTS

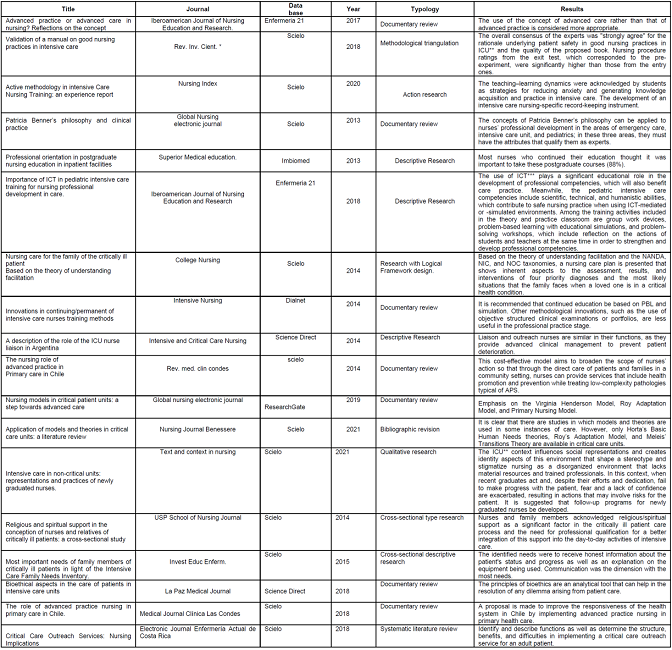

According to the analysis and methodology of the type of study, 53 % of the 18 articles were documentary reviews, whereas 47% were qualitative or quantitative studies. The characterization and approach to the subject matter of the 18 articles are shown inTable I, where the year of publication, typology, and general results have been differentiated. These results, in accordance with what has been established in this study, allow us to know which topic to classify the articles in. However, it was found that several studies were related to two or all three of the following topics: advances in the nursing professional training process in the specialization for the care of the critically ill patient, application of theoretical-disciplinary approaches, trends and/or challenges in the training process

Table I. Articles (n = 18) related to the training of nursing professionals as specialists in the care of critically ill patients, 2021.

*Scientific Information Magazine

**intensive care unit

***Technology of the information and communication

NANDA: North American Nursing Diagnosis Association

NIC: Classification of nursing interventions

NOC: Classification of Nursing results

PBL: Problem-Based Learning

APS: Atención Primaria en Salud

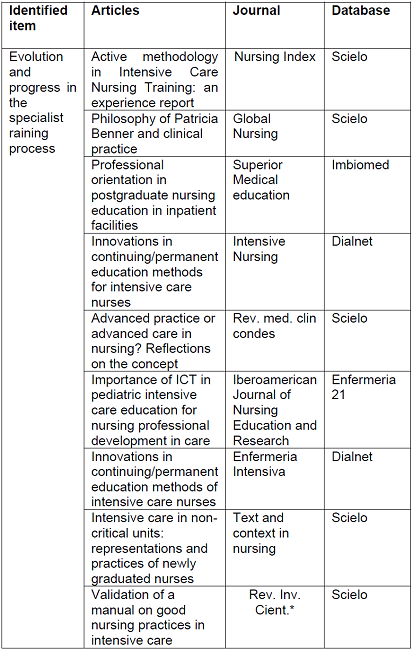

Articles about the evolution and progress of the training process are shown in Table II. The guiding question was: How has the specialization training process evolved? The results of these studies demonstrate an important change in the teaching-learning processes of nursing professionals caring for critically ill patients as well as the evolution of traditional education and its methods toward more active ones that involve student participation in order to improve their learning. In this regard, specialization has been at the forefront due to changes in educational training processes that have occurred globally.

Table II. Evolution and progress in the training process of nurses specialized in the care of critically ill patients.

ICT: Technology of the information and communication

Regarding theoretical and disciplinary approaches used in the training of critical care nurses, articles related to the applicability of theoretical and conceptual models of ICU nursing were found, although their use is still very limited. The guiding question was: What theoretical and conceptual approaches of the discipline are applicable to critical care? It was found that although the 14-needs model of Virginia is still used, nursing care models that involve the family of the critically ill patient are used along with models that use the term "advanced care" and others that highlight spiritual care and the importance of bioethics in the care of critically ill patients. Although Patricia Benner’s "from novice to expert" model emphasized competency-based training, it also served as a guide for the management of human resources in the ICU setting. Table III.

Table III. Theoretical and disciplinary approaches in the training process of specialists involved in the care of critically ill patients.

ICU: intensive care unit

Articles found on the challenges and innovations identified as trends in the training process are shown in Table IV. Faced with the guiding question: What trends and challenges are presented for the training process of the training specialist? Five influential globalizing trends were found for the training process of the critical care specialist nurse:The information age and the use of VR, Demographic diversity: aging, ethnic diversity, chronically ill patients, end-of-life care, and a shift in emphasis from curative care to health promotion and prevention; the latter being visible in studies reporting that the presence of a critical care nurse specialist in primary health care areas is essential, the culture of competent care, health system reforms in countries, the boom in pharmacology and genomic medicine cause ethical issues, and unexpected events derived from new treatments.

DISCUSSION

Progress in the training process

The analysis of articles grouped by similarity of contents reveals that in terms of advances in the training processes of critical care nursing specialists, traditional methods of training have been overcome, such as the master class based on the role of the teacher, passivity of participants, and memorization of contents, paving the way for active strategies and methodologies in critical care nursing education aimed at acquiring and practicing competencies. Problem-based learning and simulation have been highlighted in previous studies(12,13), promotion of experiences, care concept maps (12,14) that enable critical and reflective learning of nursing care in intensive care, and collaborative work, thus ensuring that routine nursing care gives way to nursing care tailored to the needs of each patient and his/her clinical situation.

It is also mentioned that the professional orientation prior to postgraduate studies favors the knowledge and orientation that the nursing professional can receive from the undergraduate level(12)from the option of elective and in-depth courses. OECD and European Union legislation proposed that competencies were a primary component of student learning processes, teacher training, and quality assessment of institutions. Teaching-learning at the university must be able to train people for lifelong learning. In the knowledge society, each person has to assimilate a knowledge base and effective strategies; You have to know what to think and how to act in realistic life situations(15).

The need to improve critical thinking continues to grow in order to gain competence in the ability to develop and apply theory in practice, thereby fostering professional identity, discipline visibility, and the achievement of global health agenda challenges from a humanistic perspective(15).

In Europe, it is widely accepted that because of the increasing complexity and holistic nature of care, the nursing role is essential for providing evidence-based care in the ICU, for which the nursing professional must master a specific set of skills, knowledge, and attitudes, competencies of knowing, doing, and being (15,16) that can be linked to the knowledge patterns described by Barbara Carper(16) and demonstrated through the rubrics used during training practices.

The approach, from beginner to expert, leads to competency-based training, which will be reflected in nursing work or personal and professional development. In this field, where professionals have direct contact with patients and apply values, abilities, and attitudes, there are skills that can only be linked to practical knowledge. Personal development is based on these three major factors, which demonstrate the extraordinary ability of the nurse to resolve any conflict or problem that may arise in the clinical setting as well as to face conflicting situations and ethical dilemmas involved in caring for the health, life, illness, and death (17).

On the contrary, among the teaching-learning methods and strategies needed for the acquisition of competencies and the achievement of learning objectives, VR is a teaching tool that provides an immersive, multisensory environment, set in whatever is desired to be shown.

Nowadays, the education of health professionals is shifting toward virtual education, requiring that educators and students adapt to new technological tools that enable them to meet practical training needs(18,19,20). VR involves immersive, three-dimensional VR based on artificial intelligence(21), mixed reality(22), and augmented reality.(23). Augmented reality can be thought of as a supplement to learning because it allows students to build their knowledge through the visualization of abstract phenomena obtained from the digital world, but it requires a whole pedagogical scaffolding for the knowledge to be reinforced(24).

Although VR is not a modern technology, it has only recently gained popularity because of the use of these tools by large corporations and institutions. With the emergence of modern technologies such as smartphones, televisions, and "smart" computers, VR began to be integrated into these devices, making it more accessible(25).

Application of models and theories in critical care

The application of nursing models in ICUs is still limited because of work overload, overvaluation of the biomedical model, and a lack of knowledge about its usefulness in practice(24). Nursing care models facilitate the development of skills required in the cognitive processes during the training process, thereby contributing to reflective and autonomous professional practice. The Primary Nursing model, also called “bedside nurse” model, is one of the models that can be used in the training practices. This model, developed by Marie Manthey, proposes patient-centered nursing care through an interpersonal and human relationship while promoting four fundamental principles: Responsibility for the comprehensive care of a group of patients according to their needs; Case method: by assigning a set number of patients for whom he or she organizes and coordinates all care activities; Communication, as interlocutor for the care of patients with the health team, with the patient and his or her family; Continuity of care(26)). The model of Virginia Henderson, which focuses on the nursing role, establishes 14 components to be evaluated in patient care, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of the person that takes into account the patient’s environment and recovery. It is a model to be used in the nursing process, and it describes a nurse-patient relationship as a "substitute" when the patient is dependent. It establishes a teaching role for nursing while considering dignified care during the dying process (26).

The adaptive model by Roy and the organizational theory by Weick are other applicability models in ICU patient care. Judy Davidson’s model aims to reduce the psychological effects on the family member, such as depression, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder, by including him/her as a member of the care team and contributing to the well-being of the loved one. On the contrary, the theory of understanding consolidates a comprehensive care model that promotes visibility, continuity, efficiency, quality, and excellence of care and reduces the hostility that the intensive care experience generates in patients’ families (27).

Among other influential thinkers in the development of theory and practice, Schön's reflection in action, also known as “Schön’s reflective practicum,” stands out because it questions the structure of knowledge in action and allows for its modification by restructuring new action strategies. Action becomes the object of reflection. The reflective learning intervention of Gross-Forneris and Peden-McAlpine and dual processing as a guide to clinical practice by Jefford et al. are also highlighted.(26)

Trends and challenges

The trend is to achieve an education that is more focused on the student’s self-regulation but supervised by a mediator (teacher or nurse on duty) in order to form more critical and reflective specialists who are more humane and supportive and connected to the realities and people they may care for(12). The use of research and cultural competence are basic requirements for professional practice so that critical care nurses are prepared to understand and provide quality nursing care to people from diverse backgrounds and lifestyles in a highly technological context(28).

However, because the ICU is a closed unit with limited quotas and highly specialized personnel, its functions are limited to the unit itself, leaving the most basic units without this coverage and allowing patients in the process of decompensation to deteriorate rapidly in less complex wards because of a lack of staff with training in that specific area of care. Therefore, critical care extension services, which are currently in use in Europe, Canada, Australia, and Argentina, are novel(29).

The implementation of outreach teams includes nursing care and support, with critical care nurses at the forefront of the group to provide "critical care without walls" through actions that impact patient mortality, prevent clinical deterioration, and provide advanced clinical management for patient deterioration. They are thus, the first link in the rapid response system. They constitute an autonomous body that actively monitors patient evolution in the emergency room and other services and have even developed a strategy that can have an impact on primary health care.

Other challenges to be considered during the training process were as follows:

- Inclusion of a clinical simulation program in the curricula so that future professionals can learn while acting and enter the real-world clinical environments with greater safety and practical knowledge (12).

-Incorporation and integration of a critical care nursing best practice program for reducing variation in care, transfer evidence from research to practice, transmit nursing knowledge base, assist with clinical decision making, identify gaps in nursing research, discontinue interventions that have negligible effect or cause harm, reduce care, and incorporate evidence-based nursing into daily practice.

- The implementation of advanced practice nursing in primary health care (PHC) as a model that aims to broaden the scope of action of the critical care nurse specialist so that through direct patient and family care in a community setting, the specialist nurse can provide services that incorporate health promotion and prevention while treating low complexity pathologies that are typical of PHC.

- The COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to reconsider the role of institutions that train health professionals in terms of not only ensuring the continuity of the teaching-learning processes but also becoming an active agent of intervention using alternative methods(6). It is highlighted if a model of guidelines implies Academic continuity with distance education presenting an intensive use of technology, digital resources, and simulation with virtual scenarios. Communication- emotional companionship and social Responsiveness and responsibility allowing the development of competencies in students.

- Nurse-led autonomous or extended clinical practice, including advanced direct care interventions, care plan monitoring, and care optimization. Subcategories included the following: providing advanced or complex therapeutic interventions; engaging in nurse-led case management; making differential diagnoses; engaging in comprehensive patient assessment; optimizing care by establishing boundaries between disciplines and services; and identifying risks and interventions to promote patient or individual safety.

CONCLUSION

The review allowed us to know how the training processes of the nursing specialist for critical care have been improving according to the needs and demands of the national and global educational regulations for care directly from the critical patient. Although Nursing models and theories provide the guiding approach to care that must be provided in ICUs, their application is not yet widespread. Currently, new challenges are generated to reconsider the role of the institutions that train health professionals, highlighting distance education with an intensive use of technology, digital resources and simulation with virtual scenarios with social responsibility and allowing the development of competencies in students.

REFERENCIAS

1. Sociedad española de enfermería de urgencias y emergencias. Reflections for a Critical Care Nursing Specialty Proposal. http://www.enfermeriadeurgencias.com [ Links ]

2. Escobar-Castellanos B, Cid-Henriquez, P. El Cuidado de enfermería y la ética derivados del avance tecnológico en salud, Acta Bioethica, 2018; 24(1): 39-46.http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S1726-569X2018000100039 [ Links ]

3. Asociación Colombiana de Facultades de Enfermería, ACOFAEN. Postgraduate Education in Nursing. 2020.https://acofaen.org.co/images/Comisiones_ACOFAEN/Formacio%C3%ACn_posgradual.pdf. [ Links ]

4. Monteiro LA. Florence Nightingale on public health nursing, American Journal of Public Health, 1985; 75 (2):181-186. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.2.181 [ Links ]

5. Stanley D, Sherratt A. Lamp light on leadership: clinical leadership and Florence Nightingale. J Nurs Manag 2010; 18: 115-21. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01051.x [ Links ]

6. Young P, Hortis De Smith V, Chambi MC. Finn, B.C. and Nightingale F. (1820-1910), Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), 101 years after her death. Rev Med Chil. 2011 Jun;139(6):807-13. PMID: 22051764. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872011000600017 [ Links ]

7. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet, 2010; 376 (9756): 1923-1958https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [ Links ]

8. Ruiz J, Moya S. Evaluation of skills and learning outcomes in skills and habilities in students of Pediatry Degree at the University of Barcelona. Educación Médica. 2020; 21(2):127-136.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2018.08.007 [ Links ]

9. López M, Arriaga JGC, Nigenda Álvarez JP, González RT, Elizondo-Leal JA, Valdez-García JE, et al. Virtual reality vs traditional education: is there any advantage in human neuroanatomy teaching. Computers & Electrical Engineering. 2021;93: 107-282.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107282 [ Links ]

10. López Cabrera MV, Hernández-Rangel E, Mejía GP, Cerano Fuentes JL. Factors that enable the adoption of educational technology in medical schools. Educación Médica. 2019; 20: 3-9.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1575181317301444. [ Links ]

11. Hoyos Botero C. Un Modelo para Investigación Documental: Guía Teórico-Práctica sobre Construcción de Estados del Arte con Importantes Reflexiones sobre la Investigación. 2008.https://es.scribd.com/doc/16281901/UN-MODELO-PARA-INVESTIGACION-DOCUMENTAL-29-04-08 [ Links ]

12. Dos Santos Emilia CG, De Almeida YS, Iannuzzi NA, Costa R De Oliveira A, De Avellar Ramos JB. Teaching nursing in an intensive care unit by active methodology: experience report. The Index Enferm Journal. 2019 (28):139-142.http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962019000200011&lng=es [ Links ]

13. Moreno CM, Barragán JA. The pedagogical practice of the nursing care teacher: from behaviorism to constructivism. Praxis & Saber. 2020; 11(26):10255. https://doi.org/10.19053/22160159.v11.n26.2020.10255 [ Links ]

14. Manso-López A, Garrido-Tapia E. Higher medical education: use of concept maps in the teaching-learning process. Correo Científico Médico. 2020; 24 (2).https://revcocmed.sld.cu/index.php/cocmed/article/view/3466 [ Links ]

15. Moyano GB, Sosa NI. Towards a state of the art in the perspectives of development of competencies in the training of Nursing in Intensive Care. Rev Arg de Ter Int. 2019: 36(1):http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6337-2424 [ Links ]

16. Díaz Mass DC, Soto Lesmes VI. Competencias de enfermeras para gestionar el cuidado directo en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos de adultos. Rev Cubana Enfermer [Internet]. 2020; 36(3): e3446. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-03192020000300019&lng=es. Epub 01-Sep-2020 [ Links ]

17. Carrillo Algarra AJ, García Serrano L, Cárdenas Orjuela CM, Díaz Sánchez IR, Yabrudy Wilches N. Review of Patricia Benner's philosophy in clinical practice. Enfermeria Global 2013;12(32): 346-361.http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412013000400021&lng=es. [ Links ]

18. Gómez JM, Montes WB. Implementing virtual reality in anatomy teaching, a need in the training of health professionals. 2021. Morfolia, Vol. 13(3):11-18.https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/morfolia/article/view/100003/82110 [ Links ]

19. Chytas D, Johnson EO, Piagkou M, Mazarakis A, Babis GC, Chronopoulos E, et al. The role of augmented reality in Anatomical education: an overview. Annals of Anatomy. 2020; 229: 151463.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2020.151463 [ Links ]

20. Lange AK, Koch J, Beck A, Neugebauer T, Watzema F, Wrona KJ, et al. Learning with virtual reality in nursing education: qualitative interview study among nursing students using the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. J.M.I.R. Nursing. 2020; 3(1): e20249.https://doi.org/10.2196/20249 [ Links ]

21. Sadeghi AH, Maat APWM, Taverne YJHJ, Cornelissen R, Dingemans AC, Bogers AJJC, et al. Virtual reality and artificial intelligence for 3-dimensional planning of lung segmentectomies. J.T.C.V.S. Techniques. 2021; (l. 7): 309-321.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjtc.2021.03.016 [ Links ]

22. Tang ZN, Hui Y, Hu LH, Yu Y, Zhang WB, Peng X. Application of mixed reality technique for the surgery of oral and maxillofacial tumors, Beijing da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020; 52 (6): 1124-1129.https://doi.org/10.19723/j.issn.1671-167X.2020.06.023 [ Links ]

23. Ille S, Ohlerth AK, Colle D, Colle H, Dragoy O, Goodden J, et al. Augmented reality for the virtual dissection of white matter pathways. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2021; 163 (4); 895-903.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-020-04545-w [ Links ]

24. Ruiz Cerrillo S. Teaching anatomy and physiology through augmented and virtual reality. Innovación educativa. 2019; 19(79), 57-76. Disponible enhttp://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-26732019000100057&lng=es&tlng=es [ Links ]

25. Magallanes Rodríguez JS, Rodríguez Aspiazu QJ, Carpio Magallón Ángel M, López García MR. Simulation and virtual reality applied to education. RECIAMUC 2021; 5(2), 101-110.https://doi.org/10.26820/reciamuc/5.(2).abril.2021.101-110 [ Links ]

26. Avilés Reinoso L, Soto Núñez C. Nursing models in critical care units: step toward advanced nursing care Enferm. glob. 2014; 13(34): 323-329.http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412014000200015&lng=es [ Links ]

27. Galarce Vargas FJ, Espinoza Arancibia MJ, Zamorano Zúñiga G, Ceballos Vásquez PA. Servicios de Extensión de Cuidados Críticos: Implicancias para Enfermería. Enfermería Actual de Costa Rica [Internet]. 2018 Dec ; (35): 173-184. Available from: http://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1409-45682018000200173&lng=en. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/revenf.v0i35.30759. [ Links ]

28. Valdez-García JE, Cabrera L, Jiménez Martínez MV, M. de LÁ, Díaz Elizondo JA, Dávila Rivas JAG et al. I prepare myself to help: response of medical and Health sciences schools to COVID-19 Investigación en Educación Médica. 2020. 35: 85-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/facmed.20075057e.2020.35.20230 [ Links ]

29. Vialart Vidal MN. Didactic strategies for the virtualization of the teachingearning process in the times of COVID-19. Educación Médica superior. 2020; 34: e2594. [ Links ]

Received: June 21, 2023; Accepted: October 13, 2023

texto en

texto en