My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal (Internet)

On-line version ISSN 1698-6946

Med. oral patol. oral cir.bucal (Internet) vol.11 n.1 Jan./Feb. 2006

ORAL SURGERY

Parotid sialolithiasis in Stensen´s duct

Daniel Torres Lagares 1, Sebastián Barranco Piedra 2, María Ángeles Serrera Figallo 3, (1) Profesor del Master de Cirugía Bucal. Equipo Docente de Cirugía Bucal ABSTRACT

Salivary duct lithiasis is a condition characterized by the obstruction of a

salivary gland or its excretory duct due to the formation of calcareous

concretions or sialoliths resulting in salivary ectasia and even provoking the

subsequent dilation of the salivary gland. Key words: Lithiasis, parotid diseases. salivary duct calculi. RESUMEN La litiasis salival es una afectación consistente en la obstrucción mecánica

de una glándula salival o de su conducto excretor, debido a la formación de

concreciones calcáreas o sialolitos, lo que determina una ectasía salival,

pudiendo provocar la dilatación posterior de la glándula. Palabras clave: Litiasis, enfermedades parotídeas, cálculos salivares

ductales.

Pilar Hita Iglesias 4, Angel Martínez-Sahuquillo Márquez 5, José Luis Gutiérrez Pérez 6

(2) Colaborador Clínico. Equipo Docente de Cirugía Bucal

(3) Becaria F.P.D.I. Equipo Docente de Medicina Bucal

(4) Becaria F.P.D.I. Equipo Docente de Cirugía Bucal

(5) Profesor Titular de Medicina Bucal

(6) Profesor Titular Vinculado de Cirugía Bucal. Director del Master de Cirugía Bucal.

Equipo Docente de Cirugía Bucal. Universidad de Sevilla

Sialolithiasis accounts for 30% of salivary diseases and most commonly involves

the submaxillary gland (83 to 94%) and less frequently the parotid (4 to 10%)

and sublingual glands (1 to 7%).

The present study reports the case of a 45-year-old male patient complaining of

bad breath and foul-tasting mouth at meal times and presenting with a salivary

calculus in left Stensen´s duct. Once the patient was diagnosed, the sialolith

was surgically removed using local anesthesia. In this paper we have also

updated a series of concepts related to the etiology, diagnosis and treatment of

sialolithiasis.

La sialolitiasis supone el 30 % de la patología salival y afecta principalmente

a las glándulas submaxilares (83 a 94 %), seguida por la glándula parótida (4

a 10 %) y las glándulas sublinguales (1 a 7 %).

En este trabajo presentamos el caso de un paciente varón de 45 años que

presentaba mal olor y sabor de boca en el momento de las comidas y afecto de un

cálculo salival a nivel del conducto de Stensen izquierdo. Tras el diagnóstico

de la sintomatología, el sialolito se eliminó quirúrgicamente bajo anestesia

local. De igual forma realizamos una actualización de conceptos en relación

con la etiología, diagnóstico y tratamiento de esta patología.

Introduction

Salivary duct lithiasis is a condition characterized by the obstruction of a salivary gland or its excretory duct due to the formation of calcareous concretions or sialoliths, resulting in salivary ectasia and even provoking the subsequent dilation of the salivary gland. A further effect may be the infection of the salivary gland which may result in chronic sialadenitis (1).

The clinical symptoms are clear and allow for an easy diagnosis, whenever we take into account that pain is only one of the symptoms and that it does not occur in 17% of the cases (2).

Sialolithiasis accounts for 30% of salivary diseases and it most commonly involves the submaxillary glands (83 to 94%) and less frequently the parotid (4 to 10%) and sublingual glands (1 to 7%). Sialolithiasis usually appears around the age of 40, though it can also have an early onset in teenagers and it can also affect old patients. It has a predilection for male patients, particularly in the case of parotid gland lithiasis (1).

Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the etiology of these calculi: mechanical, inflammatory, chemical, neurogenic, infectious, strange bodies, etc. Anyhow, it seems that the combination of a variety of these factors usually provokes the precipitation of the amorphous tricalcic phosphate, which, once crystallized and transformed into hydroxyapatite becomes the initial focus. From this moment on, it acts as a catalyst that attracts and supports the proliferation of new deposits of different substances (2)

Salivary calculi affecting the parotid gland are usually unilateral and are located in the duct. Their size is smaller than submaxillary sialoliths, most of them < 1 cm. (3, 4).

Different conditions should be considered when carrying out the differential diagnosis of salivary duct lithiasis. The unilateral enlargement of the parotid region is characterized by the presence of a discreet, palpable mass or either a diffuse swelling. Sialodenitis may be considered in the absence of this mass. A superficial mass in the salivary gland may suggest either a case of lymphadenitis, preauricular cyst, sebaceous cyst, benign lymphoid hyperplasia or extraparotid tumor.

A mass inside the salivary gland may suggest either a neoplasia (benign or malignant), an intraparotid adenopathy or a hamartoma (5). The clinical symptoms of malignant tumors include rapid growth, facial nerve palsy, petrous texture, pain and a higher incidence rate among elderly patients.

The differential diagnosis of the asymptomatic bilateral enlargement of the parotid region includes benign lymphoepithelial lesions (Mikulicz syndrome), Sjogrenis syndrome and sialadenitis secondary to alcoholism, long-term treatment with different drugs (iodine and heavy metals) and Whartin´s tumor. Painful bilateral enlargements may result from radiotherapy or may be secondary to viral sialadenitis (including mumps) whenever they co-occur with other systemic symptoms. Among the conditions presenting with diffuse facial swelling of the parotid region, but unrelated to the glands, we must mention masseter muscle hypertrophy, lesions in the temporomandibular articulation and osteomyelitis affecting the ascending maxillary branch. It is also important to differentiate sialoliths from other soft tissue calcifications. Whereas the former are characterized by pain and swelling of the salivary gland, other calcifications such as those of the lymphatic ganglia are symptom free.

In the case of small calculi it is advisable to try a non-surgical treatment (spasmolitics, diet, antibiotics, etc) (6).

Odontologists and stomatologists are in charge, together with other sanitary professionals, of the diagnosis of salivary glands diseases. They must be aware of them and must be able to apply modern imaging techniques for their diagnosis and, if necessary, manage and treat these diseases.

Case Study

We report the case of a 45-year-old male patient complaining from acute pain, suppuration and unilateral inflammation in the parotid region. He also refers bad breath and foul-tasting mouth, both salty and sour at the same time, most frequently at meal times. These symptoms disappear within a relatively short period, never more than 2 hrs. The patient had been suffering form these symptoms for 9 days and he had not noticed temperature or any further symptomatology.

Intra-oral examination revealed a swelling, which was fibrous to the touch and was not adhered to any deeper structure. Orthopantomography was negative for a suspected diagnosis of obstructive sialolithiasis. However, a simple radiography showed a sialolith located in the excretory duct (Figure 1, A). To perform the radiological diagnosis a radiographic film is placed at the level of the swelling and the beam perpendicular to the film; this way the whole calcification located in the cheek is reflected in the film.

Our first decision was to treat the symptoms. Pain was treated with analgesic-anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen, 600 mg every 8 hrs for a period of 7 days) and the bacterian infection was treated with antibiotics (amoxicillin 875mg and clavulanic acid 125 mg every 8 hrs for a period of one week). The patient should follow a diet rich in proteins and liquids, including acid food and drinks to stimulate the production of saliva. Once the symptoms were controlled, we planned the treatment of the disease. The location and size of the calculus discarded medical therapy aiming at the spontaneous discharge of the sialolith. Instead, we decided on the surgical removal of the calculus. The first step of our treatment, once the sialolith had been located, was to achieve its immobilization by means of suture to prevent it from moving along the duct during the surgical procedure (Figure 1, B).

Then, we performed an incision on the swollen region (Figure 1, C) and a small pressure exerted at this level of the cheek provoked the discharge of the sialolith through the incision (Figure 1, D). The size of the sialolith coincided with the radiographic image.

Once the sialolith was out, the duct should be repaired and cicatrize. Two possible solutions were considered in this sense, anastomosis of the duct by means of microsurgery or either diversion of salivary flow by creation of an oral fistula. The second possibility was the technique of choice because of its simplicity, efficacy and satisfactory results as regards the preservation of glandular function.

The margins of the lesion were separated using dissecting scissors (Figure 2). Thus the cicatrisation of the duct is hindered, preventing its obliteration and favouring the formation of a salivary fistula creating a new access to the oral cavity. In successive follow-up visits we observed the complete remission of the symptoms, the effectiveness of the salivary drainage and the normal functioning of the parotid gland.

Discussion

Salivary duct lithiasis, that is, the obstruction of a salivary gland or its excretory duct due to the presence of a sialolith is characterized by a series of symptoms. The first one is salivary duct swelling, either without any obvious reason or at meal times. This symptom lasts for a relatively short period, no more than 2 hrs and it disappears throughout the day. On some occasions, the swelling is accompanied by pain and then the patient presents with an episode of salivary colic, an acute, lacerating pain which does not last for long and disappears after 15 or 20 mins. In the case here reported, the pain referred by the patient was as characteristic as the bad breath and foul-tasting mouth (1).

The evolution of this condition is characterized by the repetition of any of these two clinical stages during successive episodes. However, the swelling of the gland tends to persist, it becomes indurated and does not recover its normal size. Our patient presented with areas of fibrous swelling in the duct (1).

The epidemiological features of our patient also coincide with those reported in the bibliography (predilection for male patients ≥ 40 yrs). Although the parotid gland is less frequently involved (4 to 10% of cases) it can not be considered strange or rare (2).

Sialoliths are usually more or less organized hard concretions, of a pale yellow colour and porous aspect. They usually have an oval or long shape, although we may also find some in the form of a cast (2).

Crystallographic studies reveal the differences between parotid and submaxillary calculi. In relation to the composition of parotid calculi we must mention the study conducted by Slomiany et al. who mention a total lipidic component of 8.5% and a mineral component of 20.2% (7).

The different chemical properties of the saliva secreted by both glands explain why parotid calculi have about 70% more organic component, 40% more proteins and 54% more lipids than submaxillary calculi (2).

The composition and size of salivary calculi has some diagnostic implications. Around 20% of submaxillary gland sialoliths and 40% of parotid ones are radiolucid due to the low mineral component of the secretion, especially in the case of parotid calculi (2).

The knowledge of the clinical symptoms is vital for the diagnosis of this condition and , as mentioned before, it is possible that the calculi be undetected despite being present. However, the ideal situation is to be able to identify them and several techniques are available for this purpose.

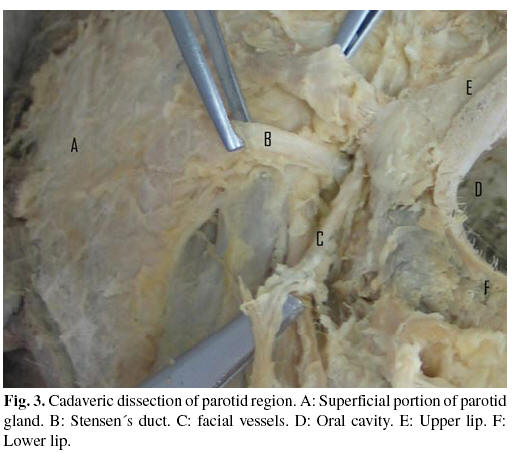

Conventional intra-oral radiography may be useful, although parotid gland sialoliths are more difficult to detect than submaxillary ones, because of the winding course of Stensen´s duct around the anterior portion of the masseter muscle and through the buccinator. In general, only the sialoliths located in the anterior part of the duct, in front of the masseter muscle, can be visualized by means of intra-oral radiography (8).

Conventional extra-oral radiography is of limited use, because most of the images of parotid gland sialoliths are superposed on the body and the maxillary branch. The sialoliths located in the distal part of Stensen´s duct or within the parotid gland are difficult to see by means of lateral intra-oral or extra-oral radiographies. Nevertheless, a posteroanterior image of the swollen cheek may make the sialolith become detached from the bony area, thus becoming visible. Even so, the sialoliths with low mineral content may become darkened by the shadows cast by dense soft tissues in posteroanterior images (8).

Sialography is the most adequate technique to detect salivary gland calculi, as it allows for the visualization of the whole duct system. Submaxillary and parotid glands are more easily studied by means of this technique than sublingual glands. However, sialography is not indicated in the case of acute infections or patients sensitive to substances containing iodine. It should not be used either if a radiopaque calculus is observed in the distal portion of the duct, as this technique could move the calculus to the most proximal portion of the duct, thereby complicating its removal (9). Sialography is also useful to locate obstructions that cannot be detected by means of bidimensional radiography, especially whenever sialoliths are radiolucid or whenever they are not present (as is the case with stenosis) (10).

Computerized tomography and nuclear magnetic resonance can also be used for the detection of sialoliths. Although these techniques are more complex and expensive than sialography, they are not invasive. According to some authors, CT scan is the technique of choice to detect calculi inside or near the salivary glands. Its sensitivity makes it possible to detect recently calcified calculi which go undetected through conventional radiography (9).

Though scyntigraphy is not clearly indicated for the diagnosis of sialolithiasis, on some occasions, it may be useful as a complementary exploratory technique. A functional study of salivary glands is accomplished by means of scyntigraphy. When the Tc 99m-pertechnetate is intravenously administered, it concentrates and is excreted through such glandular structures as the salivary gland, thyroid and mammary glands. After a few minutes, it is possible to observe the radioisotope in the salivary gland ducts and it achieves its higher concentration level 30-45 minutes after infusion (8).

Scyntigraphy allows for the analysis of all salivary glands at the same time. In the event of a suspected sialolithiasis, this technique is mainly applied when sialography is not indicated and in patients with non permeable glandular ducts. Functional salivary pathology (either lithiasic or not) can be detected by the increase, reduction or absence of radioisotope uptake areas (8).

Recent studies show that ultrasonography may also be useful for the diagnosis of renal sialoliths (11).

In short, there is not a single technique for the diagnosis of salivary gland sialolithiasis and we must select the most adequate technique according to the circumstances and pathology to be treated. We must obtain an accurate diagnosis and at the same time we should minimize the risk and inconvenience for the patient.

As regards the case here reported, painful episodes were usually satisfactorily treated with spasmolitics, whereas infectious complications had to be treated with antibiotics such as spiramicine and anti-inflammatory drugs which are mostly eliminated through the saliva.

A diet rich in proteins and liquids including acid food and drinks is also advisable in order to avoid the formation of further calculi in the salivary gland (1).

In the case of small calculi the treatment of choice should be medical instead of surgical. The patient can be administered natural sialogogues such as small slices of lemon or sialogogue medication. Drugs stimulating ductal contraction such as pilocarpine can be prescribed as well as the application of short-wave infrared heating . However, if the calculus is of a medium or large size, a salivary colic may occur and the calculus may not be discharged.

Surgical removal of the calculus (or even of the whole gland) has traditionally been used as an alternative to medical therapy, whenever the latter was not possible or proved ineffective. The case here reported exemplifies this therapeutic management.

Surgical removal of the calculus has the disadvantage of compromising the facial nerve, depending on the location of the sialolith. Extra-oral surgical techniques are not indicated because of the risk of leaving antiaesthetic scars and also because intra-oral surgery has proved more effective (6).

A recently published technique prevents these complications. It consists in the use of ultrasound expansive waves to provoke the fragmentation of the calculus. Moreover, it does not require anesthesia, sedation or analgesia. The procedure lasts for about 30 minutes and is administered in a series of successive weekly sessions until all the fragments of the calculus are eliminated, using sialogogues as coadjuvant therapy (12).

Some authors treat sialolithiasis by means of intraductal instillation of penicillin or saline. The low recurrence rate proves, according to these authors, the efficacy of this method in comparison with the systemic administration of drugs. Moreover, this therapy offers the advantage of acting at different levels: it dilates ducts, dislodges sialoliths adherent to the walls of ducts and flushes out the obstructing coagulated albumin (13).

As regards the surgical removal of calculi located in Stensen´s duct, there are several possible solutions. The most conservative technique is the anastomosis of stensen´s duct by means of microsurgery. Another feasible option is the creation of a salivary fistula, which is an easier technique yielding equally positive results as far as glandular function is concerned. In the case of this latter technique, once the sialolith has been removed, the margins of the lesion are separated thus avoiding duct collapse in the cicatrisation process. This way we favour the formation of a salivary fistula acting as a new access to the oral cavity (14).

Inhibition of salivary gland function is hardly employed, with the exception of cases of sialorrhea, due to the possible complications associated to this technique and the reduction of salivary flow it provokes. The technique consists in the closure of the duct with suture once the calculus has been removed. This provokes the collapse and inflammation of the gland. Atrophy is achieved by means of pressure and the administration of successive drugs to attain this goal (14).

All the therapies here described require the previous treatment of symptoms and all of them confirm that there is not a single therapeutic approach to the treatment of obstructive sialolithiasis, as it can be successfully treated using different techniques and even a combination of some of them. The use of one or another technique depends to a large extent on the sialolith size, location and composition.

![]() Correspondence

Correspondence

Dr. Daniel Torres Lagares

C/ Sta Mª Valverde 2 3ºC; 41008 Sevilla

Tlfno 661 336 740 Fax 954 481 129

E-mail: danieltl@us.es

Received: 27-04-2005

Accepted: 30-10-2005

References

1. Lustran J, Regev E, Melamed Y. Sioalolithiasis: a survey on 245 patients and review of the literatura. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990;19:135-8. [ Links ]

2. Bodner L. Parotid sialolithiasis. J Laryngol Otol 1999;113:266-7. [ Links ]

3. Seifert G, Miehlke A, Hanbrich J, Chilla R, eds. Diseases of the salivary glands: pathology, diagnosis, treatment, facial nerve surgery. Stuttgart:George Thime Verlag; 1986. p. 85-90. [ Links ]

4. Ottaviani F, Galli A, Lucia MB, Ventura G. Bilateral parotid sialolithiasis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and immunoglobulin G multiple myeloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997;83:552-4. [ Links ]

5. Marchal F, Becker M, Vavrina J, Dulgerov P, Lehmann W. Diagnostic et traitement des sialolithiases. Bull Med Suisses 1998;79:1023-8. [ Links ]

6. Dulguerov P, Marchal F, Lehmann W. Postparotidectomy facial nerve paralysis: possible etiologic factors and results with routine facial nerve monitoring.Laryngoscope 1999;109:754-62. [ Links ]

7. Slomiany BL, Murty VL, Aono M, Slomiany A, Mandel ID. Lipid composition of human parotid salivary gland stones. J Dent Res 1983;62:866-9. [ Links ]

8. Goaz PW, White SC, eds. Radiología oral principios e interpretación. Barcelona: Mosby; 1995. p. 127-229. [ Links ]

9. Hong KH, Yang YS. Sialolithiasis in the sublingual gland. J Laryngol Otol 2003;117:905-7. [ Links ]

10. Becker M, Marchal F, Becker CD, Dulguerov P, Georgakopoulos G, Lehmann W et al. Sialolithiasis and salivary ductal stenosis: diagnostic accuracy of MR sialography with a three-dimensional extended-phase conjugate-symmetry rapid spin-echo sequence. Radiology 2000;217:347-58. [ Links ]

11. Nguyen BD. Demonstration of renal lithiasis on technetium-99m MDP bone scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med 2000;25:380-2 [ Links ]

12. Schlegel N, Brette MD, Cussenot I, Monteil JP. Extracorporeal lithotripsy in the treatment of salivary lithiasis. A prospective study apropos of 27 cases. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 2001;118:373-7. [ Links ]

13. Antoniades D, Harrison JD, Epivatianos A, Papanayotou P. Treatment of chronic sialadenitis by intraductal penicillin or saline. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;62:431-4. [ Links ]

14. Steinberg MJ, Herrera AF. Management of parotid duct injuries Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005;99:136-41. [ Links ]

text in

text in