My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Pharmacy Practice (Granada)

On-line version ISSN 1886-3655Print version ISSN 1885-642X

Pharmacy Pract (Granada) vol.9 n.4 Redondela Oct./Dec. 2011

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Alcohol attitudes and behaviors among faculty at U.S. schools and colleges of pharmacy

Actitudes y comportamientos sobre el alcohol entre académicos de las escuelas y facultades de farmacia en Estados Unidos

Schlesselman L.S.1, Nobre C.2, English C.D.3

1PharmD. Assistant Clinical Professor & Director, Office of Assessmente & Acreditation, School of Pharmacy, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT (United States)

2PharmD. School of Pharmacy, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT (United States).

3PharmD. Assistant Professor. Albany College of Pharmacy & Health Sciences. Colchester, VT (United States)

ABSTRACT

Despite attempts to control college-aged drinking, binge and underage drinking continues at colleges and universities. Although often underutilized, faculty have the potential to influence students' behaviors and attitudes towards drinking. Little information is available pertaining to college faculty drinking patterns, views on drinking, or their influence on college drinking. What little information is available predates the economic crisis, mandates for increased alcohol education, and the American Pharmacists Association's call for increased alcohol awareness in pharmacists.

Objectives: This study was designed to determine alcohol use patterns and viewpoints among faculty at U.S. colleges of pharmacy, in particular, to identify alcohol practices among faculty, use of alcohol with their students, mentioning alcohol in classroom as a social norm, and perceived drinking norms within their colleagues.

Methods: Following Institution Review Board approval, 2809 invitations were emailed to U.S. pharmacy faculty for this survey-based study. The survey consisted of demographic questions, the World Health Organization Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), and questions pertaining to personal and institution attitudes on drinking and on drinking with students.

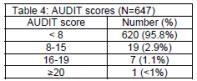

Results: More than 96% of 753 respondents had a total AUDIT score <8. Males and preceptors were more likely to have higher AUDIT scores. More than 75% of faculty reported never drinking with students.

Conclusion: In order to help pharmacy students address the extent of their alcohol use and misuse, pharmacy faculty must address their own use, along with their own and their institutions attitudes and behaviors towards alcohol use.

Key words: Alcohol Drinking. Schools, Pharmacy. United States.

RESUMEN

A pesar de los intentos de control de la ingesta de alcohol en las facultades, la juerga y la bebida entre menores continúa en facultades y universidades. Aunque a menudo infrautilizados, los académicos tienen la posibilidad de influenciar las actitudes y comportamientos de los estudiantes sobre la bebida. Hay poca información disponible sobre los hábitos de bebida de los académicos, visión de la bebida, o su influencia sobre la bebida en las facultades. La poca información disponible anterior a la crisis económica recomienda aumentar la educación sobre el alcohol y la Asociación de Americana de Farmacéuticos pide un aumento de la concienciación sobre el alcohol entre los farmacéuticos.

Objetivos: Este estudio fue diseñado para determinar los patrones de uso de alcohol y los puntos de vista de los académicos en las facultades de farmacia de Estados Unidos, en particular, identificar las prácticas con el alcohol entre académicos, el uso de alcohol con sus estudiantes, menciones al alcohol en clases como hábito social, y hábitos percibidos sobre el alcohol con sus colegas.

Métodos: Después de la aprobación del Comité de Investigación de la Institución, se enviaron por correo 2809 invitaciones a académicos de farmacia de Estados Unidos para esta encuesta. El cuestionario comprendía preguntas demográficas, el World Health Organization Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) y preguntas relativas a actitudes personales y de la institución sobre el beber y el beber con estudiantes.

Resultados: Más del 96% de los 753 respondentes tenían una puntuación total en el AUDIT de <8. Los hombres y los preceptores tenían puntuaciones AUDIT mayores. Más del 75% de los académicos reportaron no beber nunca con estudiantes.

Conclusión: Para ayudar a los estudiantes de farmacia a afrontar el extendido uso y abuso del alcohol, los académicos de farmacia deben afrontar su propio uso, así como sus actitudes y comportamientos y las de sus instituciones sobre el consumo de alcohol.

Palabras clave: Consumo de Bebidas Alcohólicas. Escuelas de Farmacia. Estados Unidos.

Introduction

Binge drinking and underage drinking in college students are two problems that parents, educators, government officials, and researchers have struggled with for years. While many programs exist to educate America's youth about the risks and consequences of alcohol use and misuse, an overwhelming number of youth still continue to use and abuse alcohol. In a self-reported questionnaire about their own drinking, 31% of college students met the criteria for a diagnosis of alcohol abuse and 6% met criteria for a diagnosis of alcohol dependence.1 In our companion study of alcohol use in pharmacy students2, we found consumption of hazardous amounts of alcohol, as defined by an AUDIT score greater than 8, in more than 25% of pharmacy students, including nearly 2% with a score greater than or equal to 20.

Where are we failing? Researchers have struggled with this topic for years, and despite the multitude of approaches taken there are an infinite number of variables that must be considered. Studies have given way to a range of predictors that can be used to help target and educate those most at risk for alcohol misuse. As a result, colleges and universities have developed countless prevention programs, ranging from alcohol education, counseling services, alternative alcohol-free activities and restrictive policies.3,4 Nonetheless alcohol misuse on college campuses persist.

For schools of pharmacy, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) continues to provide guidance on how to address the issue of student and faculty substance abuse. In 1988, AACP adopted guidelines for developing chemical impairment programs at pharmacy schools. These guidelines were updated again in 1999 in attempts to further advocate assistance for students and faculty who are chemically impaired. In 2010, AACP established a special committee on substance abuse and pharmacy education. The committee's final report updated the association's previous curricular guidelines on substance abuse, recommends expanded continuing education for pharmacists on substance abuse, and recommends faculty and staff development to ensure a strong knowledge base pertaining to substance abuse.5

College faculty have extensive contact with the very students about whom we are concerned. Although often underutilized, faculty have the potential to influence these students' behaviors and attitudes towards drinking. Yet, very little information can be found concerning college faculty, in particular their own views on drinking, their drinking patterns, and their influence on college drinking. Baldwin and colleagues6 reported that the majority of full-time faculty in the colleges of pharmacy throughout the United States had consumed an alcoholic beverage in the past year, with 10.4% reporting that they experienced an increase in alcoholic use after becoming faculty at their institute. More than 40% of respondents believed health care professionals to be at greater risk of alcohol misuse.7 Perkins found that faculty view student alcohol misuse as a significant problem, and reported a concern, but few actively involved themselves in prevention efforts.8 Faculty have passively incorporated alcohol education into their routine lectures via curriculum infusion. Some faculty have even claimed to have utilized academic performance in students to reveal emerging drinking problems among students.8 However, current studies do not address the faculty's personal alcohol use and if their perceived norms are indirectly influencing the very college students they are striving to protect from the misuse of alcohol.

This study was designed to determine alcohol use patterns among faculty at schools and colleges of pharmacy throughout the United States and their perceived drinking norms within their colleagues. We also hope to identify the percentage of faculty who drink alcohol with their students or mention alcohol as a social norm, and perceived drinking norms within their colleagues.

Methods

Following determination of exemption by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Connecticut, invitations to participate in a 31-question survey-based study were emailed to 2809 faculty members at schools and colleges of pharmacy in the United States. In lieu of informed consent, information sheets were included as part of the email invitation and as part of the online survey. The survey, administered through SurveyMonkey, consisted of three sections: 12 demographic questions, the 8-question World Health Organizations Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) to determine alcohol dependency and categorize potential alcohol abuse in participants, and 9 additional questions pertaining to personal and institution attitudes on drinking and drinking with students.

The AUDIT questionnaire provides scores reflecting low, medium, and high degrees of alcohol dependence.9 The AUDIT score range of 8-15 represents a medium level of alcohol problems. For scores in the range of 8-15, the recommended intervention is advice focused on reduction of hazardous drinking. Scores of 16 and above represent a high level of alcohol problems. As such, the recommended intervention for scores of 16-19 is brief counseling and continued monitoring, while scores of 20 or higher warrant further diagnostic evaluation for alcohol dependence. The AUDIT questionnaire is divided into 3 domains: hazardous alcohol use, dependence symptoms, and harmful alcohol use.

The study population consisted of faculty at U.S. schools and colleges of pharmacy. Full-time and part-time faculty and administrators with titles of assistant, associate, or full professor, instructor, and lecturer were included. Emeritus professors and individuals with titles suspected to be staff positions, rather than faculty, were excluded. Faculty email addresses were obtained from the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy 2008-2009 roster.

Upon completion of the study, descriptive statistics were performed for the demographic data and the personal and institution attitudes on drinking, followed by Chi-squared analysis. AUDIT scores were calculated for all respondents. As recommended by the World Health Organization, scores of 8-15 will be considered consistent with a medium level alcohol problem and scores greater than or equal to 16 will be considered a high level alcohol problem.9

Results

Demographics

Email invitations were sent to 2809 faculty. Of these, 275 email invitations either bounced back as undeliverable or as having previously opted out of any SurveyMonkey-administered surveys, leaving 2534 delivered email invitations. From these, 753 faculty completed the survey for a response rate of 29.7%.

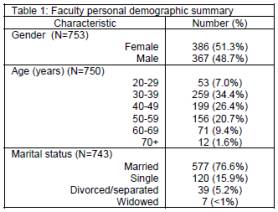

Personal and professional characteristics of respondents are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. No statistical difference in the gender of respondents was noted. Faculty in their thirties (34.4%) accounted for the largest number of respondents. More than three-fourth of respondents reported being married. The majority of respondents reported holding a Doctor of Pharmacy degree (64.4%) and/or identified their primary discipline as pharmacy practice (60.4%). Nearly one-third (30.5%) of respondents reported having more than one degree. No difference was noted in response rate by non-tenure track and tenured/tenure-track faculty.

Drinking practices of faculty

Of the 753 respondents, 106 (14.1%) reported never drinking alcohol. (Table 3) Male faculty were statistically more likely to report never drinking alcohol than female faculty (p=0.034). No statistical differences in reports of never drinking were found between faculty over versus under 40 years of age, married versus unmarried faculty, or those in pharmacy practice versus other disciplines.

For the remaining 647 respondents, the total AUDIT scores were calculated. Including the faculty who reported never drinking alcohol, 96.4% of respondents had a total AUDIT score less than 8. (Table 4) Of those faculty with an AUDIT score >8, only three were under the age of 30. These 3 faculty were all in pharmacy practice with PharmD degrees. Male faculty and those faculty who serve as preceptors were statistically more likely than female faculty and those who are not preceptors to have an AUDIT score greater than or equal to 8 (p=0.019 and p<0.005, respectively). No statistical difference was noted between faculty under the age of 40 years compared to those =40 years old (p=0.139), married or unmarried faculty (p=0.817), pharmacy practice or other disciplines (p=1.00), non-tenure or tenured/tenure-track (p=0.444), or between academic ranks (p=0.203).

In an analysis of the dependence subset of questions, 6.3% of faculty who drink have a subset score greater than or equal to 1. With a score of 1 or more, this may represent signs of dependence.

Nearly 36% of faculty who drink reported their first intoxication was before the age of 18 years, including 18 faculty who reported their first intoxication was before the age of 14 years. Another 40% reported their first intoxication was between the ages of 18-20 years but of those, 38% were of legal drinking age at the age of 18. The faculty with AUDIT scores =8 were statistically more likely to report their first intoxication was before the age of 18 years than all faculty who drink (p=0.013).

Nearly 36% of faculty who drink reported their first intoxication was before the age of 18 years, including 18 faculty who reported their first intoxication was before the age of 14 years. Another 40% reported their first intoxication was between the ages of 18-20 years but of those, 38% were of legal drinking age at the age of 18. The faculty with AUDIT scores =8 were statistically more likely to report their first intoxication was before the age of 18 years than all faculty who drink (p=0.013).

When asked what percentage of pharmacy faculty drink, the majority of faculty felt that their pharmacy faculty colleagues drink alcohol with nearly 90% of respondents felt that at least 80% of faculty drink alcohol. When asked if they think other faculty drink more than they do, 639 (84.9%) were of the opinion that others did or might drink more than they do, while only 15.1% felt that others did not drink more. Of those faculty members with AUDIT scores =8, 18 (66.7%) of them felt that other faculty do or might drink more than they do. When asked which is worse, 87.1% of respondents were of the opinion that smoking cigarettes was worse than drinking alcohol. All but one of the faculty with an AUDIT score =8 felt that smoking cigarettes was worse than drinking alcohol.

Personal and institutional attitudes and behavior towards drinking with students

When the topic of the lecture is not alcohol-related, nearly two-thirds (64.5%) of faculty never mention recreational drinking of alcohol in class, while approximately 7% mention alcohol 2 or more times per semester. (Table 5) Faculty with AUDIT scores <8 were not statistically less likely to mention alcohol than those who with higher AUDIT scores (p=0.213).

More than 75% of respondents report never drinking alcohol with their students, yet, only 23.6% of respondents felt it was inappropriate to do so. Less than 2% of respondents felt it was always appropriate to drink with their students, while nearly 75% reported that drinking with students was appropriate in certain situations. Frequency of drinking with students and views on appropriateness of drinking with students did not differ between younger faculty (under 30 years old) and their older colleagues (p=0.101 and p=0.490, respectively). Faculty with AUDIT scores <8 were statistically more likely to drink with students than those with higher AUDIT scores (p<0.0005) but did not have statistically different views on whether it was appropriate (p=0.815). None of the younger faculty with elevated AUDIT scores drink with students.

When asked if their school sponsored events at which alcohol is served to faculty and students together, 343 (45.6%) reported that they did have events involving alcohol.

Discussion

The use of the AUDIT tool provided us with a standardized approach to determining level of alcohol use and misuse. With this tool we found 4% of pharmacy faculty had AUDIT scores requiring either education or intervention. Those faculty who have the most contact with students through their precepting appear to be at increased risk of alcohol abuse. This does not differ much from Baldwin and colleagues study which found 2% of pharmacy faculty self-reported diagnosed or undiagnosed alcoholism with an additional 3% reporting "drinking problems".6 Faculty with higher AUDIT scores reported younger first intoxication. This corresponds with a previous study which found that individuals with first intoxication before 19 years of age were at greater risk of alcohol dependence and heavy drinking.10

Also similar to the results of the Baldwin study6 which found that 89% of faculty drink alcohol, this study found 86% of faculty respondents drink alcohol. Although we do not know what percentage of younger faculty drank alcohol during their college years, it is reassuring to note that their alcohol use is already significant less than that of pharmacy students2, especially given that Baldwin et al reported more than 10% of faculty report increased alcohol consumption after becoming faculty at their institute.6

It is heartening that faculty are aware of the hazards of cigarette smoking but faculty also need an increased awareness of the risks associated with alcohol. Even though only one-fourth of faculty drink alcohol with their students, most did not consider it wrong to do so. Interestingly, faculty with lower AUDIT scores were more likely to drink with students than those with scores >8. Faculty with lower scores may simply view alcohol consumption as part of a social gathering and feel they have nothing to hide about their own alcohol use, while those with elevated AUDIT scores may feel they must hide their drinking. As with casually mentioning alcohol in the classroom, social drinking with students portrays alcohol consumption as a social norm that is supported by the faculty and, in many cases, by the institution. Nearly half of respondents reported that their school sponsored events attended by both faculty and students at which alcohol was served.

A limitation of the survey tool was an inability to determine, among participants who did not drink, why they did not drink. We had not identified this as an issue when we previously administered the survey to pharmacy students simply because such a small number of students reported not drinking. Having received emails from faculty in support of our project and mentioning that they do not drink, we learned that some of these faculty do not drink for personal reasons while others are already in recovery.

Another interesting question that could have been asked was whether the faculty members felt they had a drinking problem. The use of the AUDIT tool eliminated those faculty who felt they had a drinking problem but whose actual AUDIT score did not support this. During the study we received comments from numerous faculty stating that they "knew" they would have a high AUDIT score. The number of comments received exceeded the actual number of faculty with high AUDIT scores, therefore more faculty think they have a drinking problem than the AUDIT tool found. Additional questions, particularly for those faculty in pharmacy practice who serve as preceptors, may also have allowed for further comparison with the Kenna and Wood's study which found that 12% of pharmacists report heavy episodic alcohol consumption, defined as 5 or more drinks at once.11

When considering the response rate, the potential reasons of non-responders might be considered. It would be interesting to know if the lack of response was due to disinterest or possibly to shame or fear to confront the reality of alcohol consumption.

Further investigation could be aimed at determining the exact number of schools of pharmacy that host events during which faculty and students drink. Because this was an anonymous survey, we are unable to ascertain exactly how many schools this represents or if all schools are represented in this sample. Despite this limitation, a large percentage of U.S. pharmacy schools continue to promote alcohol consumption among their faculty and students.

Conclusions

Pharmacy faculty, even those under the age of 30 years of age, have a lower incidence of hazardous drinking compared to pharmacy students, as identified by AUDIT scores greater than 8, than do pharmacy students. Yet, pharmacy faculty continue to perceive drinking with pharmacy students as socially acceptable. Faculty also continue to mention alcohol as a social norm in the classroom. Pharmacy schools also continue to host events at which faculty and students both drink. In order to help pharmacy students address the extent of their alcohol use and misuse, pharmacy faculty must address their own use. Faculty must also work to address their own and their institutions attitudes and behaviors towards alcohol use, whether by discontinuing events at which faculty and students drink alcohol together or to consider their own responsibility in reducing student drinking.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or financial interests in any products or services mentioned in this article, including grants, employment, gifts, stock holdings, or honoraria.

Funding: No financial support provided for this project.

The AUDIT Questionnaire™ is a trademark of the World Health Organization

SurveyMonkey is a trademark of SurveyMonkey.com, LLC.

References

1. Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(3):263-270. [ Links ]

2. English C, Rey J, Schlesselman LS. Prevalence of hazardous alcohol use among pharmacy students at nine US schools of pharmacy. Pharm Pract (Internet) 2011;9(3):162-168. [ Links ]

3. Anderson DS, Milgram GG. Promising Practices: Campus Alcohol Strategies, Fairfax, Va: George Mason University, 2001. [ Links ]

4. Wechsler H, Kelley K, Weitzman ER, SanGiovanni JP, Seibring M. What Colleges Are Doing About Student Binge Drinking: A Survey Of College Administrators. J Amer Coll Health. 2000;48(5):219-226. [ Links ]

5. Jungnickel PW, Desimone EM, Kissack JC, Lawson LA, Murawski MM, Patterson BJ, Rospond RM, Scott DM, Athay J; AACP Special Committee on Substance Abuse and Pharmacy Education. Report of the AACP special committee on substance abuse and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):S11. [ Links ]

6. Baldwin JN, Scott DM, Jungnickel PW, Narducci WA, Prokop PA, Magelli MA. Evaluation of Alcohol and Drug Use Attitudes and Behaviors in Pharmacy College Faculty: Part I. Behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 1990;54:233-238. [ Links ]

7. Baldwin JN, Scott DM, Jungnickel PW, Narducci WA, Prokop PA, Magelli MA. Evaluation of Alcohol and Drug Use Attitudes and Behaviors in Pharmacy College Faculty: Part II. Attitudes. Am J Pharm Educ. 1990;54:239-242. [ Links ]

8. Perkins HW, Haines MP, Rice R. Misperceiving the College Drinking Norm and Related Problems: A Nationwide Study of Exposure to Prevention Information, Perceived Norms and Student Alcohol Misuse. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(4):470-478. [ Links ]

9. Babor TF, DeLaFuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary health care. WHO publication no. 89.4. Geneva, World Helth Organization. Accessed at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/who_msd_msb_01.6a.pdf (January 21, 2011). [ Links ]

10. Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R, Winter M, Wechsler H. Age of first intoxication, heavy drinking, driving after drinking and risk of unintentional injury among U.S. college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(1):23-31. [ Links ]

11. Kenna GA, Wood D. Alcohol use by health professionals. Drug Alcohol Dep. 2004;75(1):107-116. [ Links ]

Received: 6-Jun-2011

Accepted: 30-Nov-2011