INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in the prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), uncontrolled vomiting and inadequately controlled nausea remains among the most distressing for patients and continues to adversely affect patients' adherence to medication and quality of life.1,2 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has developed a guideline on the use of antiemetic drugs for CINV.3 This guideline recommends all patients who receive highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens should be offered a three-drug combination of an NK1 receptor antagonist, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, and dexamethasone. However, patients on triplet therapy still continue to experience CINV.4 Previous studies have reported that triplet therapy prevent emesis in approximately 65% to 80% of patients, with the rate of patients with no nausea at approximately 50 %-60%.5,6 This shows that there is still a need for searching of additional antiemetic agents since the ideal ultimate goal is 100% complete response.

Advance in the understanding of the pathophysiology of CINV, identification of patient risk factors, and development of new antiemetic have revolutionized the prevention and treatment of CINV.7 Olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic agent, antagonizes multiple neuronal receptors including dopamine (D1, D2, D4), serotonin (5HT2A, 5HT2C, 5HT3), alpha-1 adrenergic, histamine (H1) and multiple muscarinic receptors.8 It has been suggested that neurotransmitters dopamine and 5-HT appear to play important roles in CINV.9 Following a case report documented on the effective use of olanzapine in relieving chronic nausea in a patient with leukemia in 20006, a number of phase I and phase II studies has been conducted.10,11,12,13 A systematic review of these studies on efficacy and safety of olanzapine for the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting found that Olanzapine is efficacious and safe for prophylaxis of CINV.14 Other several observational studies have shown that olanzapine was well tolerated and effective to prevent acute, delayed, and refractory CINV and for treatment of CINV when combined with other antiemetic in patients receiving moderately and highly emetogenic chemotherapy.15,16,17,18,19

Many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been then conducted to confirm the effect of addition of olanzapine to the standard antiemetic regimen.20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 A previous meta-analysis conducted by Wang et al.33 revealed that the rate of patients achieving total control of nausea and vomiting was significantly higher in the olanzapine group. However, in this study, there were few trials included and additional clinical trials have been conducted since the publication of it. Including 4 more RCTs, a recent meta-analysis by Chiu and coworkers also reported similar findings.34 On another hand, a recent pilot study done in India showed that there was no significant difference between olanzapine and aprepitant in preventing nausea and emesis with highly emetogenic chemotherapy.31 After the publication of meta-analysis by Chiu et al.34, the largest RCT so far done in this area included 380 patients.32 In addition, other small RCTs were also published elsewhere.20,31 Therefore, taking in to account the variation in the results of the currently available data and the addition of recent trials with large sample size, we believed that a comprehensive updated meta-analysis of more recent RCTs is mandated. The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the efficacy of olanzapine in the primary prevention of CINV in patients receiving emetogenic chemotherapy in relation to other standard antiemetic.

METHODS

The meta-analysis reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.35

Population

The population consist patients having any type of cancer disease who were receiving treatment with moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy.

Study selection

RCTs were included if they met all of the following criteria:

Compare olanzapine containing regimen with other standard antiemetic regimens in prophylaxis

Articles which were published in the English language on trials involving human participants

Studies reporting at least one of two endpoints/ outcomes: no emesis/vomiting or no nausea

Studies containing only one arm (studies that evaluates safety and efficacy of olanzapine without comparators) and unpublished data were excluded.

Search strategy

The PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and EBSCO databases from inception to September 2016 using the terms "olanzapine" AND "chemotherapy-induced nausea and Vomiting" OR "nausea" OR "vomiting" OR "Emesis" OR "CINV". A manual search for additional relevant studies using references from retrieved articles was also performed. Conference abstracts were also included if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes were complete response of the acute, delayed, and overall phases after chemotherapy and no nausea in acute, delayed and overall phases. Complete response is defined as no emetic episodes and no rescue medication. Notes: If the overall phase of the efficacy endpoint was not reported, we assumed the lowest percentage in the acute and delayed phase. Subgroup analyses were also performed based on whether:

Data extraction and quality assessment

All authors independent extracted data from eligible studies onto a standardized data abstraction sheet. We extracted information on name of first author and year of publication, study design, total number of patients and number of patients in each arm, type of tumor under treatment and chemotherapy used with the degree of emetogenicity, interventions given, gender and average age of patients, and ethnicity of the study population. Disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

We followed the Cochrane hand book of data analysis and reported outcome measures to assess the summary effects of treatment by calculated odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI. A random-effects model was used in this meta-analysis because of anticipated heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity among trials was expressed as the P value (Cochran's Q statistic), where a p<0.05 and I-squared statistic >50% indicated significant heterogeneity. Absolute risk differences (RD) were compared to the multinational association of supportive care in cancer/European society of medical oncology (MASCC/ESMO) guidelines.36 According to this guidelines RD>10% is suffice to change the guideline. The analyses were carried out using Rev Man 5.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Center, Denmark) to create a forest plot and a summary finding tables.

RESULTS

Literature searches and selection

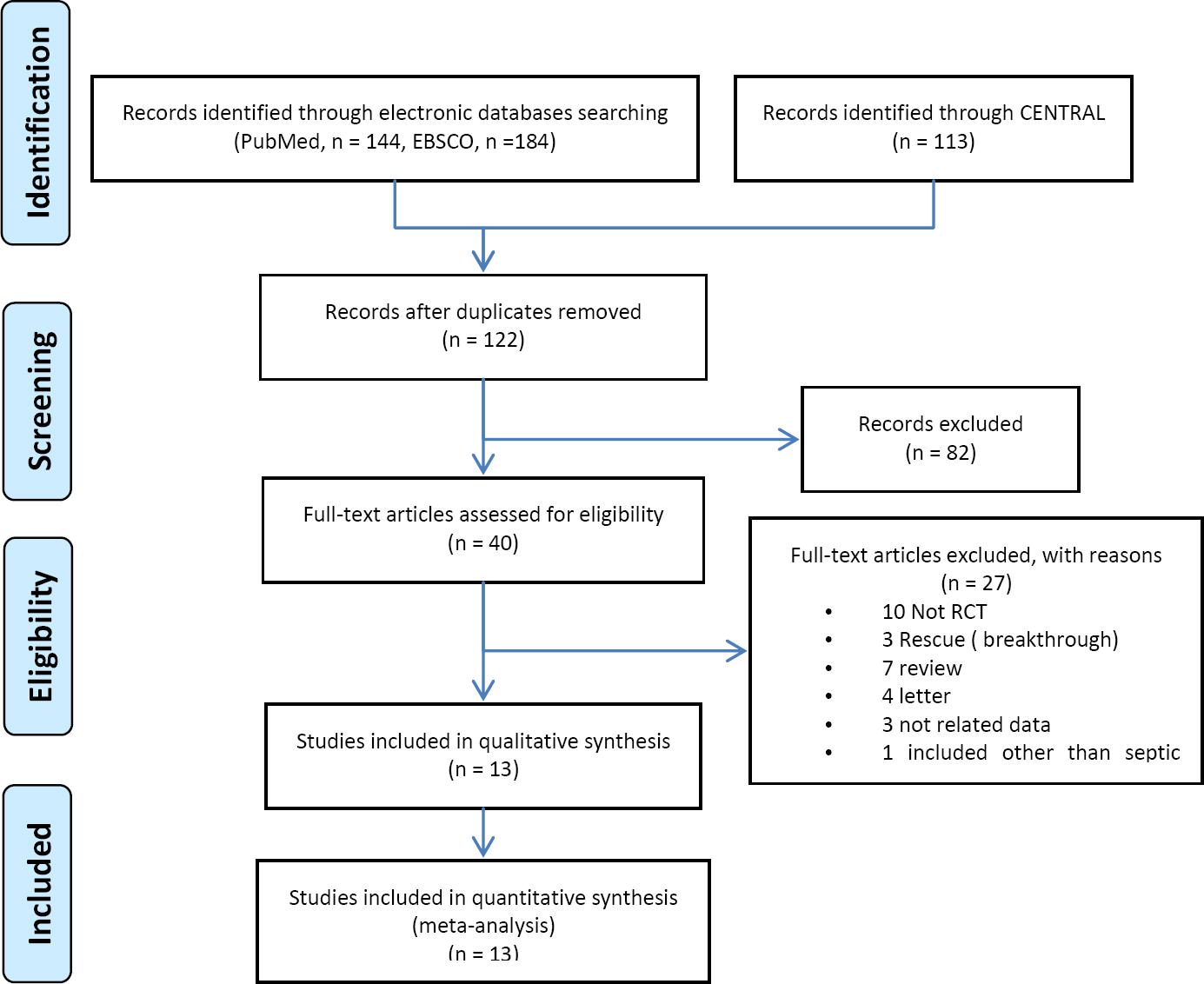

The details of our search strategy were depicted in Figure 1. Our initial research of electronic databases such as PubMed (n=144), EBSCO (n=184) and CENTRAL (n=113) yielded 441 articles, from which 122 records remained after removing 319 duplications. 82 articles were excluded on abstract assessment; after full texts were assessed for eligibility, 27 articles further removed for the following reasons; 10 were not RCTs, 7 were review articles, 4, were letters to editors, 2 were not related data and 3 RCTs were for rescue. Finally, 13 articles which fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in quantitative analysis.

Study characteristics

Finally, 13 RCTs published between 2009 and 2016 fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in the final quantitative analyses.20-32 The sample size of the included trials ranged from1723 to 38032 with a total number of 1686 patients, of which 852 were assigned to the olanzapine regimen and 834 to standard regimen without olanzapine (non-olanzapine). Baseline characteristics of participants included in RCTs are described in online appendix table 1. The age range of the participants included in RCTS was 18-8920-24,26,29,31,32 and not reported in three of the trials.25,27,28 One of the trials reported age in median (SD).30 Seven of the trails reported that either 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and/or dexamethasone with olanzapine compared with the same regimen without olanzapine24-30 and 6 of trials reported that olanzapine with NK-1 receptor antagonists (either aprepitant or fosaprepitant) containing regimen.20-23,31,32 Eleven trials reported olanzapine administered at a dose in 10 mg/day orally20-26,28,30-32, whereas two trials reported olanzapine administered in a 5 mg/day orally.27,29 Nine of the trials reported participants receiving HEC20-23,25,26,30,31,32 and four studies included patients receiving combination of MEC/HEC.24,27-29 No study reported patients receiving only MEC. Two of the studies were double-blinded RCTs20,32, three were single blinded and the rest were unblinded. Finally, 8 studies reported participants of Asian background; two from India30,31, one from Japan29 and five from China.24-28 Five of the studies reported that the patients included where from USA.20-23,32

Table 1 Summary efficacy endpoints of olanzapine compared to non-olanzapine regimen in preventing chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting OR[95%CI]

| Outcomes | Overall | Subgroup: Olanzapine as alternative or in combination with NK-1 antagonist | Subgroup: Olanzapine as alternative or in combination with dexamethasone |

|---|---|---|---|

| No vomiting in acute phase | 2.16[1.60, 2.91] p< 0.00001 |

Alternative to NK-1antagonist: 1.69 [0.93, 3.06] p=0.08 In combination with NK-1 antagonist: 2.70 [1.70, 4.28] p<0.0001 |

Alternative to dexa: 3.19 [0.63, 16.12] p=0.16 In combination with dexa: 2.03 [1.34, 3.08] p=0.0009 |

| No vomiting in delayed phase | 2.28[ 1.46, 3.54] p=0.0003 |

Alternative to NK-1antagonist: 1.19 [0.811.74] p=0.38 In combination with NK-1 antagonist: 3.32 [0.33, 32.90] p=0.31 |

Alternative to dexa: 3.83 [1.81, 8.12] p=0.0005 In combination with dexa: 1.67 [0.96, 2.90] p=0.07 |

| No vomiting in overall phase | 2.480[ 1.59, 3.86] p<0.0001 |

Alternative to NK-1antagoinst: 1.14 [0.78, 1.65] p=0.50 In combination with NK-1 antagonist: 4.21 [0.475, 37.86] p=0.20 |

Alternative to dexa: 5.11 [2.20, 11.44] p<0.0001 In combination with dexa: 1.74 [0.97, 3.11] p=0.06 |

| No nausea in acute phase | 1.68[ 1.11, 2.55] p=0.01 |

Alternative NK-1 antagonist: 1.27 [ 0.80, 2.03] p=0.31 In combination with NK-1 antagonist: NA |

Alternative to dexa: NA In combination with dexa: 1.59 [0.94, 2.69] p=0.08 |

| No nausea in delayed phase | 2.827[ 2.13, 3.74] p<0.00001 |

Alternative NK-1antagonist: 3.34 [ 2.29, 4.88] p<0.00001 In combination with NK-1 antagonist: NA |

Alternative to dexa: NA In combination with dexa: 2.83 [2.07, 3.86] p<0.00001 |

| No nausea in overall phase | 2.57[ 1.82, 3.65] p<0.00001 |

Alternative NK-1antagonist: 3.47 [2.36,5.10] p<0.00001 In combination with NK-1 antagonist: NA |

Alternative to dexa: NA In combination with dexa: 2.54 [1.73, 3.73] p<0.00001 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; NA: not enough randomized clinical to pool the results (< 2);; NK-I: neurokinin-1; dexa: dexamethasone

Efficacy endpoints

No vomiting

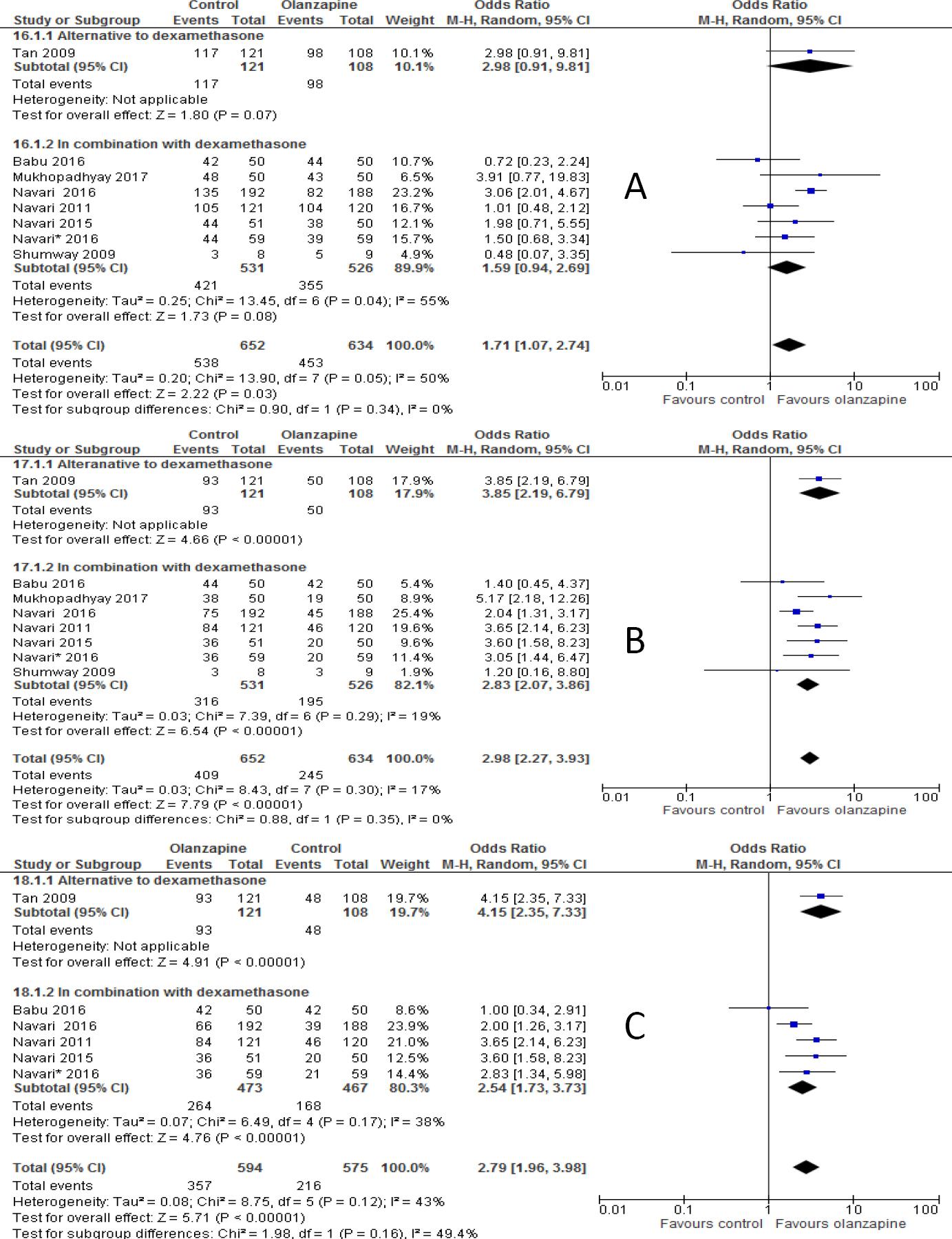

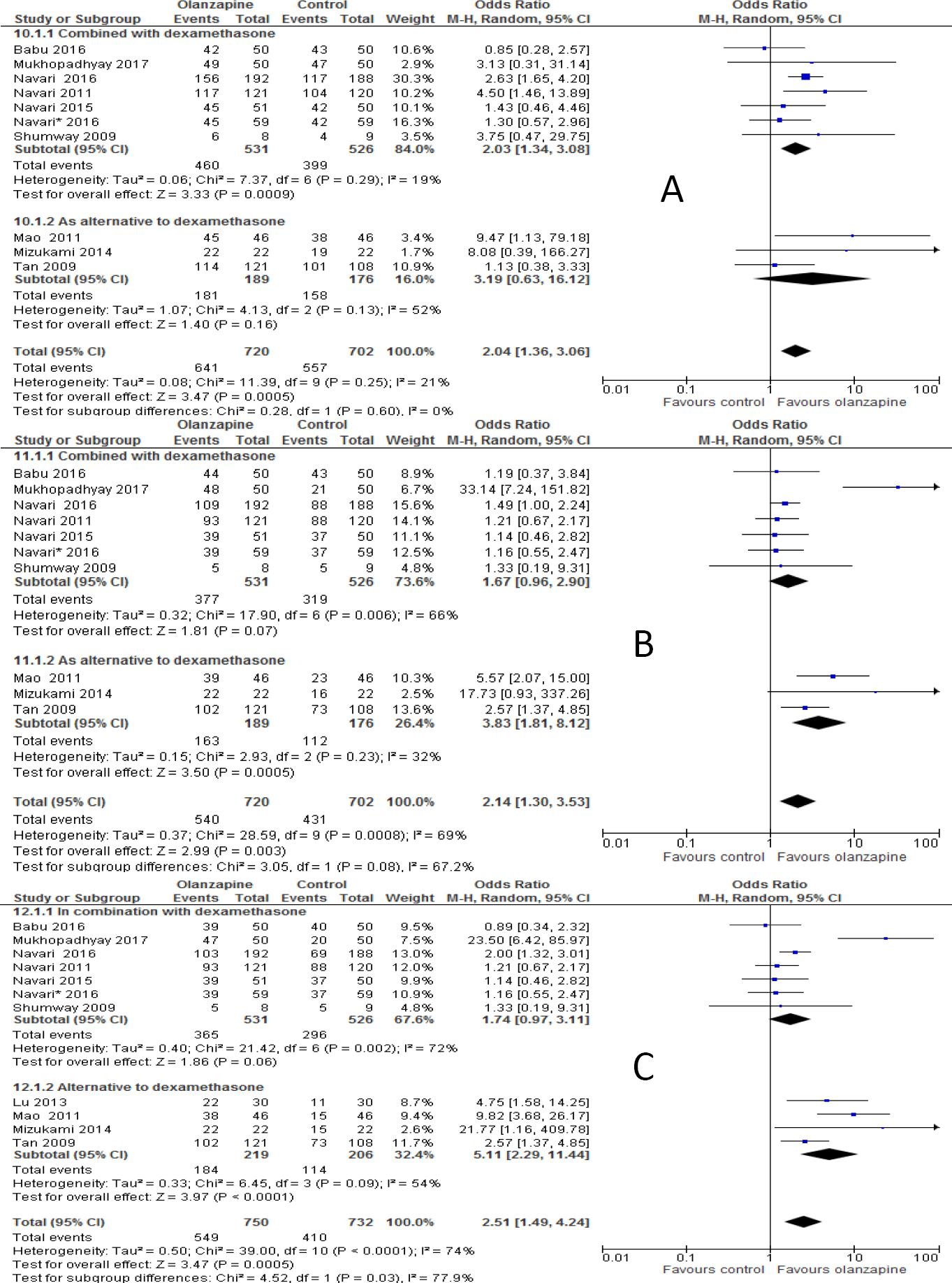

The percentages of no vomiting achieved were 87.5%, 76.2%, 73.6% in olanzapine versus 76.7%, 61.8%, and 56.4% in non-olanzapine regimen in acute, delayed and overall phases, respectively. In the 12 individual studies with subgroup staging data, the incidence of complete response was significantly higher in the patients placed on the olanzapine-containing regimen on the first day of chemotherapy (OR 2.16; 95%CI 1.60 to 2.91, p<0.00001; I-square=5%, p=0.40, Figure 2A) and delayed vomiting (OR 2.28; 95%CI 1.46 to 3.54, p=0.0003, Figure 2B). When 13 studies, combined together, the overall complete response was higher in olanzapine group compared with non-olanzapine group (OR 2.48; 95%CI 1.59 to 3.86, p<0.0001, Figure 2C).

Figure 2 Forest plot of efficacy of olanzapine containing regimen compared to standard regimen in preventing CTINV- A) No vomiting in acute phase B) No vomiting in delayed phase C) No vomiting in overall phase. M-H: Mantel-Haenszel; CI: confidence interval

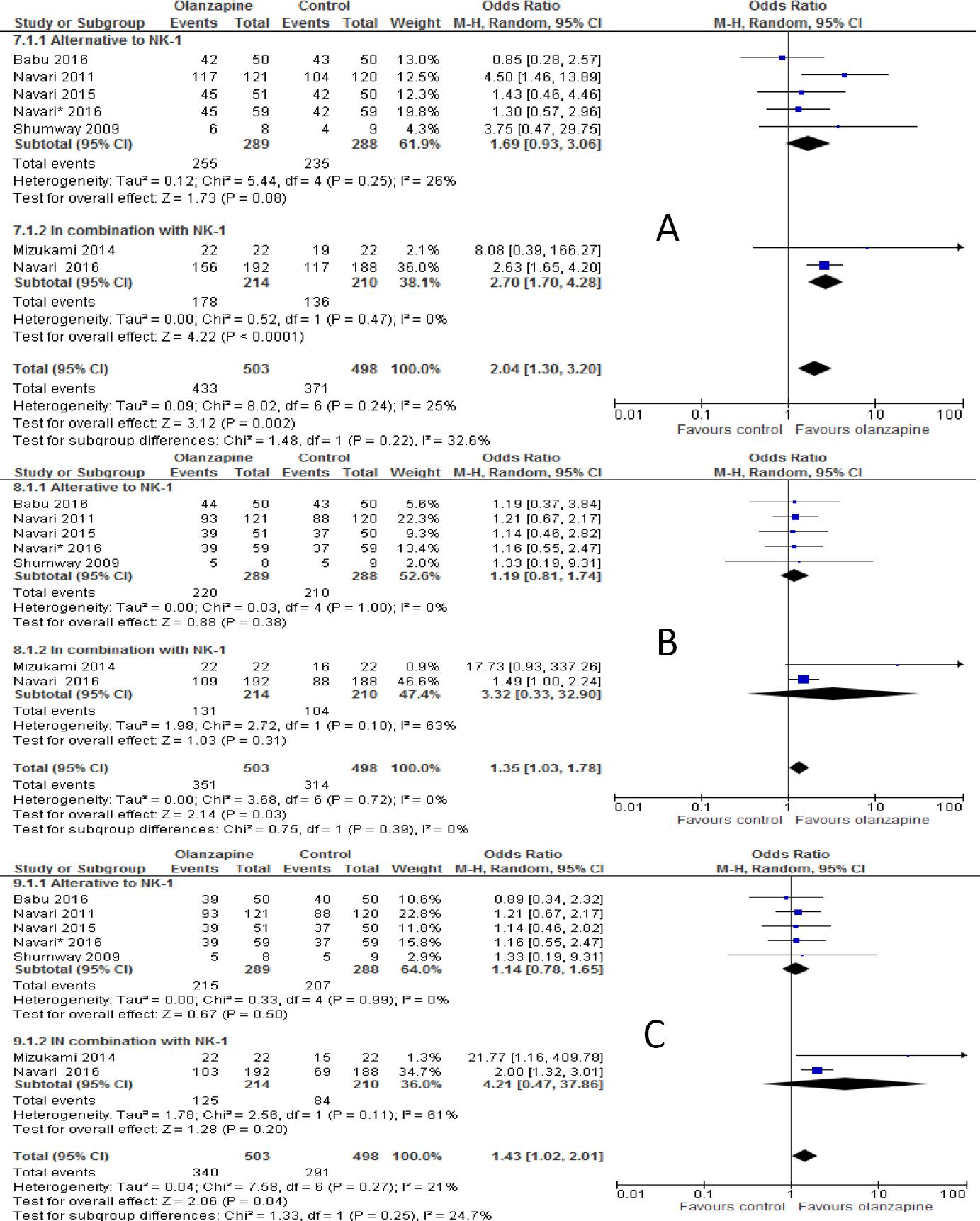

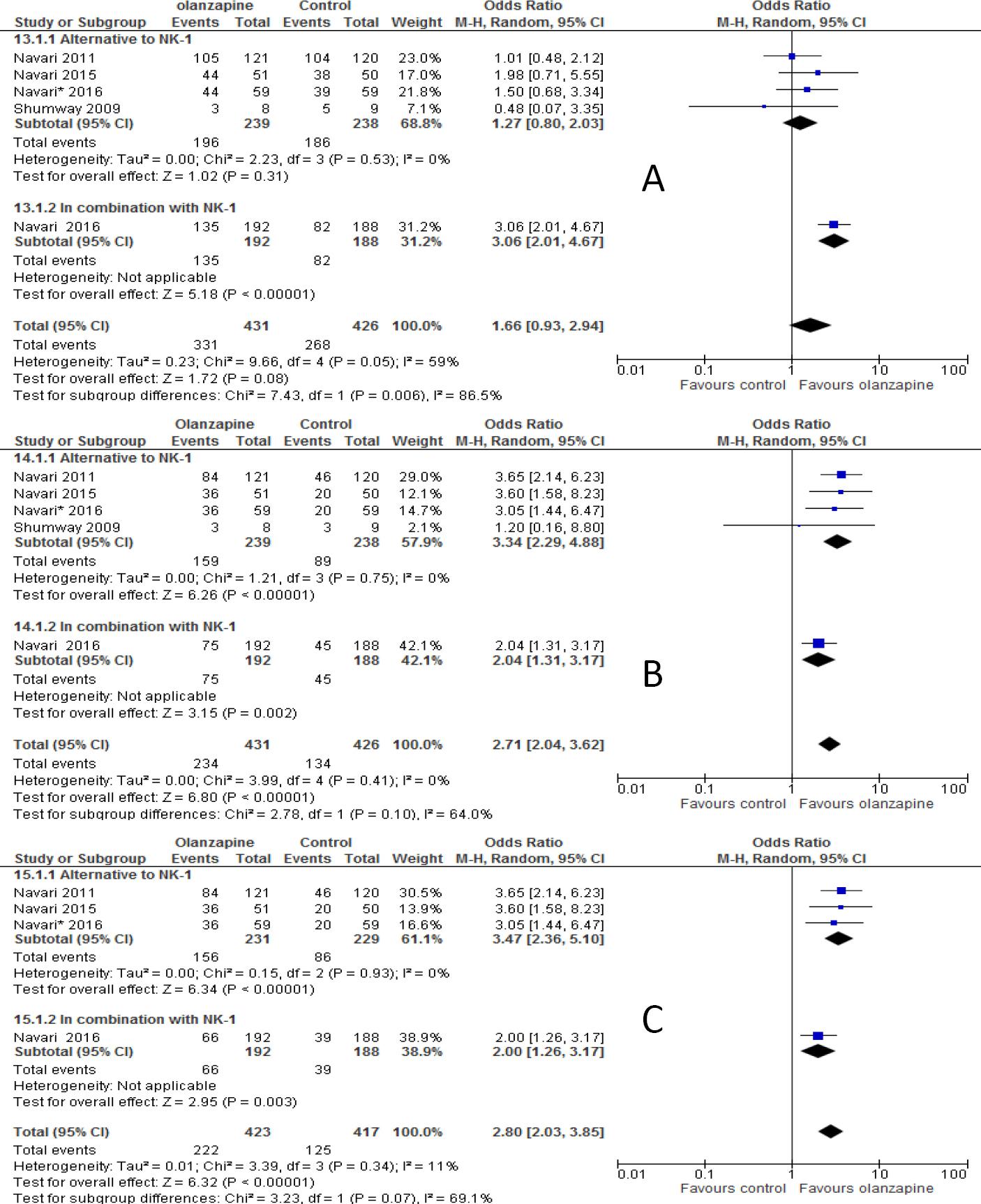

When studies included were sub-grouped into olanzapine combined with or as alternative to NK-1 receptor antagonist (either aprepitant or fosaprepitant) in the analysis, the incidence of complete response in olanzapine containing regimen was not improved compared to non-olanzapine in acute phase when olanzapine used as an alternative to NK-1 receptor antagonist (OR 1.69; 95%CI 0.93 to 3.06, p=0.08, Figure 3A), but reached statistical significance when olanzapine used combined with NK-1 receptor antagonist (OR 2.70; 95%CI 1.70 to 4.28, p<0.0001). However, complete response was not significantly different between olanzapine and NK-1 antagonist in the delayed phase either when olanzapine used as alternative (OR 1.19; 95%CI 0.81 to 1.74, p=0.38) or in combination with NK-1 antagonist (OR 3.32; 95%CI 0.33 to 32.90, p=0.31, Figure 3B). Similarly, complete response was not significantly differ between olanzapine containing regimen and non-olanzapine regimen when olanzapine used as alternative (OR 1.14; 95%CI 0.78 to 1.65, p=0.5) or combination with NK-1 antagonist (OR 4.21; 95%CI 0.47 to 37.9, p=0.20, Figure 3C) in overall phases. Another subgroup analysis showed that olanzapine containing regimen better control acute emesis when combined with dexamethasone (OR 2.03; 95%CI 1.34 to 3.08, p=0.0009) than when it is used as alternative (OR 3.19; 95%CI 0.63 to 16.12, p=0.16, Figure 4A). However, Olanzapine containing regimen showed significant difference when used as alternative to dexamethasone in preventing emesis in delayed (OR, 3.83; 95%CI, 1.81 to 8.12, p=0.0005, Figure 4B) and overall (OR 5.11; 95%CI 2.29 to 11.44, p=0.0001, Figure 4C) phases compared to when used in combination with dexamethasone. The RD computed no vomiting endpoint was 9% (range 4% to 14%) and not fulfilled the MASCC/ESMO criteria of >10% in acute phase. Certainly it fulfilled the MASCC/ESMO threshold >10% in delayed phase 17% (range 8% to 26%) and 20% (range 10% to 29%) in overall phase. This and other related risk differences were described in Table 3A.

Figure 3 Forest plot of efficacy of olanzapine containing regimen compared to standard regimen in preventing CTINV based on degree of Emetogenicity - A) No vomiting in acute phase B) No vomiting in delayed phase C) No vomiting in overall phase. HEC: highly emetogenic chemotherapy; MEC: moderately emetogenic chemotherapy; M-H: Mantel-Haenszel; CI: confidence interval

Figure 4 Forest plot of efficacy of olanzapine containing regimen compared to standard regimen in preventing CTINV based on presence or absence of NK-1 receptor antagonists- A) No vomiting in acute phase B) No vomiting in delayed phase C) No vomiting in overall phases. M-H: Mantel-Haenszel; CI: confidence interval; NK-1: neurokinin-1.

Table 2 Absolute risk difference between olanzapine and non-olanzapine regimen in preventing chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting

| Outcomes | RD (%) [95% CI] | P- for overall effect | Test for heterogeneity | MASCC/ESMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vomiting | ||||

| No vomiting in acute phase (overall) | 9[4-14] | p=0.0003 | p=0.02, 53% | No |

| No vomiting in delayed phase (overall) | 17[8-26] | p=0.0002 | p<0.00001, 77% | Yes |

| No vomiting in overall phase (overall) | 20[10-29] | p<0.0001 | p<0.00001, 80% | Yes |

| No vomiting in acute phase | Alternative to Nk-1 antagonist: 7 [2-12] | p=0.007 | p=0.45, 0% | No |

| In combination with NK-1 antagonist: 18 [10-25] | p<0.00001 | p=0.54, 0% | Yes | |

| No vomiting in delayed phase | Alternative to NK-1 antagonist: 3[0-10] | p=0.39 | p=1.0, 0% | No |

| In combination with NK-1antagonist: 17 [0-34] | p=0.6 | P=0.11, 61% | Yes | |

| No vomiting in overall phase | As alternative to NK-1antagonistt: 2 [5-9] | p=0.53 | p=0.98, 0% | No |

| In combination with NK-1antagonist: 22 [8-36] | p=0.002 | p=18, 44% | Yes | |

| No vomiting in acute phase | Alternative to dexa:: 9 [2-19] | p=0.13 | 0.52, 67% | No |

| In combination with dexa: 8 [2-14] | p=0.09 | 0.07, 49% | No | |

| No vomiting in delayed phase | Alternative to dexa: 24 [13-35] | p<0.0001 | p=0.21, 36% | Yes |

| In combination with dexa: 12 [2-26] | p=0.09 | p<0.00001, 81% | Yes | |

| No vomiting in overall phase | Alternative to dexa: 33 [161-49] | p<0.0001 | p=0.01, 72% | Yes |

| In combination with dexa: 13 [2-27] | p=0.09 | p<0.00001, 84% | Yes | |

| Nausea | ||||

| No nausea in acute phase (overall) | 8[1-15] | p=0.03 | p=0.002, 67% | No |

| No nausea in delayed phase (overall) | 22[13- 30] | p<0.00001 | p=0.004, 64% | Yes |

| No nausea in overall phase (overall) | 20[10-30] | p<0.0001 | p=0.002, 72% | Yes |

| No nausea in acute phase | Alternative to NK-1antagonist: 3 [4-10] | p=0.31 | p=0.53, 0% | No |

| In combination with NK-1: NA | NA | NA | Na | |

| No nausea in delayed phase | Alternative to NK-1antagonist: 29 [121-38] | p<0.00001 | p=0.75, 0% | Yes |

| In combination with NK-1antagonist: NA | NA | NA | Na | |

| No nausea in overall phase | Alternative to NK-1 antagonist: 30 [21-39] | p<0.00001 | p=0.93, 0% | Yes |

| In combination with NK-1 antagonist | NA | NA | Na | |

| No nausea in acute phase | Alternative to NA | NA | NA | Na |

| In combination with dexa: 8 [2-18] | p=0.13 | p=0.0006, 74% | No | |

| No nausea in delayed phase | Alternative to dexa: NA | NA | NA | Na |

| In combination With dexa: 23 [13-32] | p<0.00001 | p=0.01, 63% | Yes | |

| No nausea in overall phase | Alternative to NA | NA | NA | Na |

| In combination with dexa: 20 [8-31] | p=0.0008 | p=0.006, 72% | ||

RD: Risk difference; CI: confidence interval; NA: not enough randomized clinical to pool the results (< 2); NK-I: neurokinin-1; dexa: dexamethasone

Table 3 comparison of this study with other previously meta-analysis

| Features | Current study | Wang33 | Chiu34 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies included | 13 RCTs | 6 RCTs | 10 RCTs |

| Sample size | 1686 | 726 | 1082 |

| Findings | Olanzapine is effective in most of the endpoints analyzed compared to other standard antiemetic | Olanzapine was effective compared to other antiemetic therapy | Olanzapine was more effective than other standard antiemetic |

| In combination or as alternative to NK-1 antagonist | Not clear yet: it is uncertain whether these results will change the current standards of antiemetic practice | Not analyzed | Not analyzed |

| In combination or as alternative to dexa | The weight is towards use of combination until convincing evidence will be available | Not analyzed | Not analyzed |

Abbreviation: RCTs, randomized controlled trials; NK-1, neurokinin-1; dexa: dexamethasone

No nausea

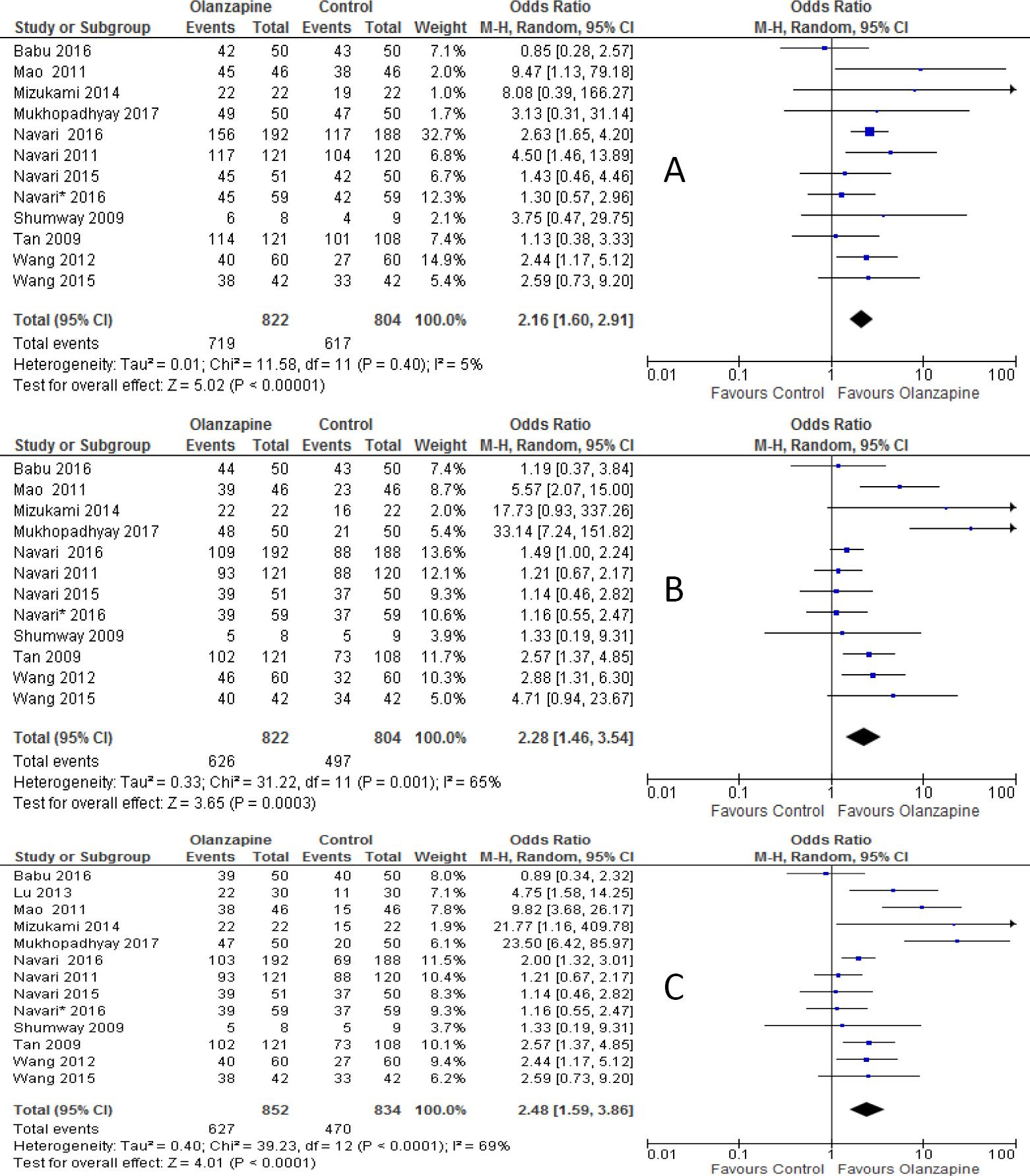

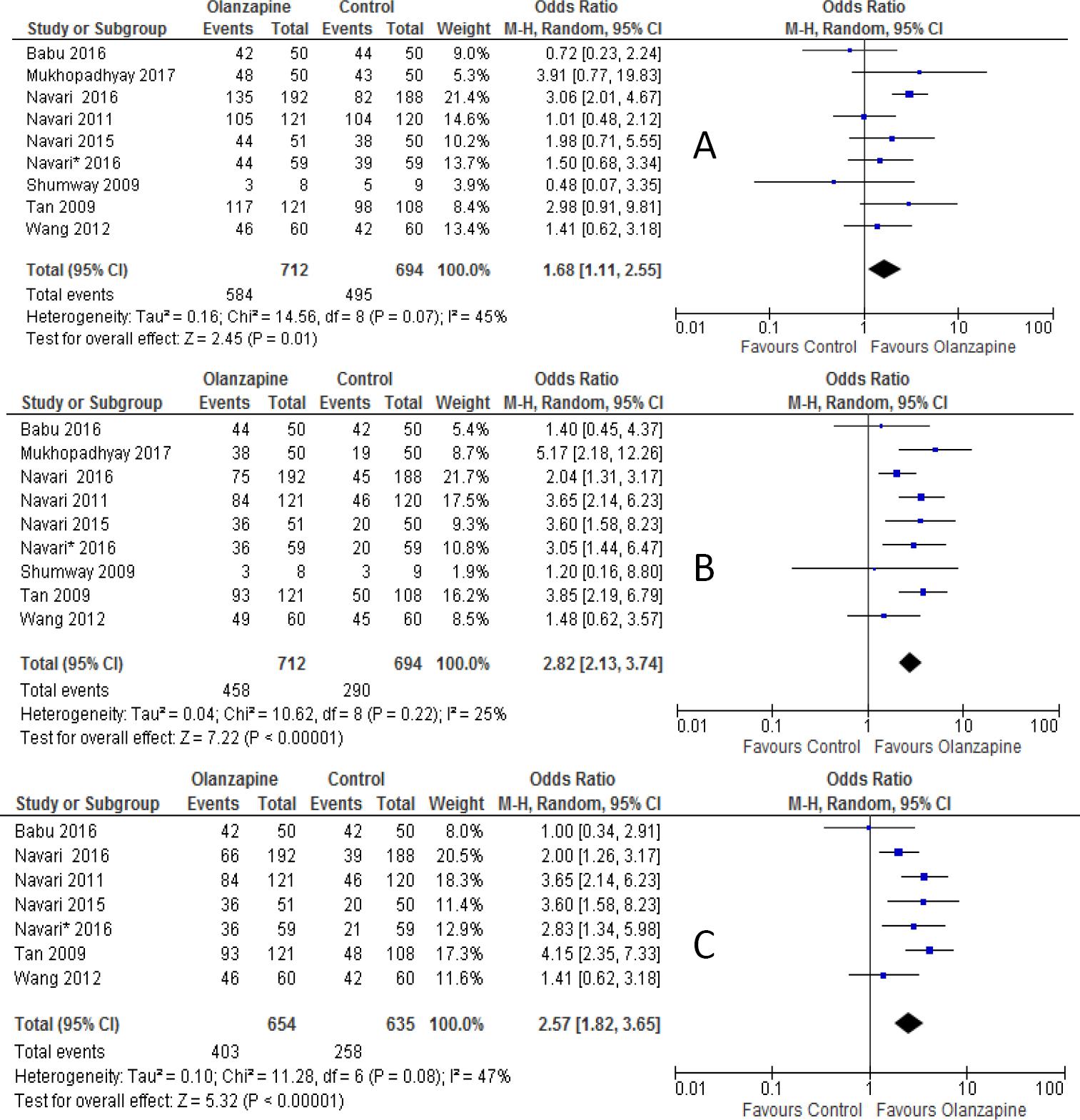

The percentages of no nausea were 82.7%, 64.3%, 61.6% in olanzapine group versus 71.3%, 41.8%, and 40.6% in non-olanzapine group in acute, delayed and overall phases, respectively. Olanzapine containing regimen showed statistically significant difference in preventing nausea compared to non-olanzapine containing regimen in the first day of chemotherapy (OR 1.68; 95%CI 1.11 to 2.55, p=0.01; I-square = 45%, p=0.09, Figure 5A). Similarly, olanzapine containing regimen showed better anti-nausea effect compared with non-olanzapine regimen in the delayed (OR, 2.77; 95%CI 2.13 to 3.74, p<0.00001, Figure 5B) and overall phase (OR 2.57; 95%CI 1.82 to 3.65, P <0.00001, Figure 5C) of antiemetic treatment.

Figure 5 Forest plot of efficacy of olanzapine containing regimen compared to standard regimen in preventing CTINV- A) No nausea in acute phase B) No nausea in delayed phase C) No nausea in overall phase. M-H: Mantel-Haenszel; CI: confidence interval

The subgroup analysis showed that there was no statistical significant difference between olanzapine containing regimen compared to non-olanzapine regimen in preventing acute nausea when it was used as an alternative to NK-1 receptor antagonist (OR 1.27; 95%CI 0.80 to 2.03, p=0.30, Figure 6A). On another hand, olanzapine treatment showed statistical superiority in preventing nausea in delayed phase (OR 3.34; 95%CI 2.29 to 4.88, p<0.00001, Figure 6B) and overall phase (OR, 3.47; 95%CI, 2.36 to 5.10, p<0.00001, Figure 6C) of chemotherapy when used as alternative agent to NK-1 antagonist. Olanzapine combined with dexamethasone didn't show superiority in preventing nausea in acute phase (OR 1.59; 95%CI 0.9 to 2.69, p=0.8, Figure 7A). On the other hand, the combination of olanzapine with dexamethasone is superior in preventing nausea in delayed phase (OR 2.83; 95%CI 2.07 to 3.86, p<0.00001, Figure 7B) and overall phase (OR 2.54; 95%CI 1.73 to 3.37, Figure 7C) of chemotherapy. The computed RD in the acute phase 8 %(range 4 to 15%) didn't meet the criteria set by MASCC/ESMO >10%, where as it met the criteria in delayed 22% (range 13% to 30%) and overall phase 20% (range 10% to 30%). Other risk differences calculated were shown in Table 3B.

Figure 6 Forest plot of efficacy of olanzapine containing regimen compared to standard regimen in preventing CTINV in combination or as alternative to neurokinin-1 antagonist (NK-1)- A) No nausea in acute phase B) No nausea in delayed phase C) No nausea in overall phase. M-H: Mantel-Haenszel; CI: confidence interval

DISCUSSION

Advances in antiemetic treatment using triple therapy brought about a significant improvement in controlling of CINV and quality of cancer patients.37 Further categorization of chemotherapeutic agents based on the degree of their emetogenicity and treatment accordingly based on established guidelines for prevention of nausea and vomiting improved the outcomes.36 Currently, combination of 5-HT3, NK-1 and dexamethasone was reported to achieve a complete response of > 80% in acute phase and 70% in delay phase of CINV, especially if aprepitant present compared with non-aprepitant regimen in patients receiving HEC.38,39,40 Palonosetron without aprepitant achieved complete responses of 75% in acute and 57% in delayed phases.41 This indicates that there still gaps to reach the ideal goal of 100% complete response. In a large RCT that involved patients with breast cancer receiving anthracycline chemotherapy showed that the combination of newer NK-1 antagonist, netupitant, palonosetron, and dexamethasone was superior to palonosetron with dexamethasone to achieve complete response in overall time period (74% vs. 67%, p=0.01) and rates of no nausea was 75% vs. 69%, p=0.2).42 These data reflects that controlling of delayed phase emesis and nausea remains a significant challenge even with triple therapy. Currently available major RCTs exploring prevention of CINV in patients receiving HEC reported that rates of nausea were over 50%.38-40 So far, many studies documented the proven beneficial effect of olanzapine for preventing CINV.20-22,24-26,33,34

In this meta-analysis, we have presented the pooled analysis of 13 RCTs (n=1686) data evaluating the effect of olanzapine in prevention of CINV and hence, the largest meta-analysis so far available in literature. The pooled analysis of this meta-analysis found that olanzapine containing regimen is statistically superior to non-olanzapine regimen in preventing CINV in 13 of the 24 analyzed efficacy parameters (Table 1). The incidences of no vomiting in olanzapine versus non-olanzapine group were 87.5% vs. 76.2%, 73.6% vs. 61.8%, and 73.6% vs. 56.4% in acute, delayed and overall phases, respectively. Similarly the incidences of no nausea were 82.7% vs.71.3%, 64.3% vs. 41.8%, and 61.6% vs. 40.6% in acute, delayed and overall phases, respectively. The bottom line is that olanzapine containing regimen is statistically superior to non-olanzapine regimen in preventing CINV in all endpoints and phases, the result consistent with the findings of Wang and Chiu.33,34 Our meta-analysis also showed that olanzapine containing regimen is clinically superior to non-olanzapine regimen in preventing CINV in 14 out of 24 parameters (Table 2), a criteria set by MASCC/ESMO of >10% threshold.36 This is a result also consistent with the result from Chiu et al.34

The subgroup analysis based on whether olanzapine used as alternative to NK-1 antagonists or in combination was conducted. The results of the analysis showed that olanzapine in combination with NK-1 antagonist was statistically superior to the use of it as an alternative in preventing acute vomiting, but not in preventing vomiting in delayed and overall phases. Olanzapine as alternative to NK-1 antagonist showed statistically superior in preventing nausea in delayed and overall phases, but not in acute phase. On one hand, olanzapine in combination with NK-1 antagonist showed clinical superiority in all phases of emesis, the criteria set by MASCC and ESMO which stated that the absolute risk benefit should be greater than 10% if clinical superiority should be anticipated. On the other hand, olanzapine showed clinical superiority when used as alternative to NK-1 antagonist in preventing nausea in delayed and overall phases, but not in acute phase. It should be noticed here that there was only one study that compared the combination of olanzapine in preventing nausea as end point and therefore subgroup analysis was not possible. The bottom line is that there still remaining gap whether olanzapine used as alternative or in combination. Therefore, there is a need of clarification whether olanzapine be effective in combination with NK-1 antagonist or as alternative.

Another subgroup analysis revealed that olanzapine in combination or as alternative to dexamethasone showed mixed results. The use of combination of olanzapine with dexamethasone is statistically superior to use of olanzapine as alternative to dexamethasone in preventing acute vomiting, delayed nausea and overall phase of nausea. On the other hand, olanzapine used as alternative to dexamethasone showed statistical superiority in preventing vomiting in delayed and overall phases. However, close observation of the clinical outcomes showed that either in combination with dexamethasone or used as alternative, olanzapine showed clinical superiority in preventing vomiting in delayed, and overall phases, but not in acute phase of vomiting (Table 2). Furthermore, olanzapine in combination with dexamethasone is clinically superior in preventing nausea in delayed and overall phases. These in turns endorse the fact that statistical significance doesn't mean clinical significance. The clinical significance shown by combination of olanzapine with dexamethasone seems to suggest that some of the effects of olanzapine may have been attributed to the presence of dexamethasone. However, these results were based on comparison of cohort of studies consisting of 7 studies (n=1,057) when olanzapine with dexamethasone compared only with three cohort studies (n=365) when olanzapine used as alternative to dexamethasone. Therefore, this indicated that there need to explore the use of olanzapine without dexamethasone in well-designed large study to see whether olanzapine can be used as single agent in the prophylaxis setting.

The most common side effects of olanzapine so far reported include Somnolence, dizziness and hyperglycemia.20,24,43 Based on personal experience and small sample analysis (n=104), Chiu et al.34 suggested to use 5 mg olanzapine for the prevention of CINV because there can be a possible potential for increasing in side effects of olanzapine with increasing dose. As the suggestion was based on small sample size, we have to wait for the conclusion till a double-blind randomized Phase II study of olanzapine 10 mg versus 5 mg by Nagashima et al.44 for emesis induced by highly emetogenic chemotherapy completed.

The strength of our study includes a rigorous search of several databases and other sources to identify eligible RCTs. To our knowledge this is the largest meta-analysis in current literature (n=1,686 participants) and therefore, more informative than the previous studies. Other specific issues addressed in this work that the previous meta-analyses failed to address were the analysis of whether olanzapine should be used with or as alternative to either NK-1 antagonist or dexamethasone. The comparison of current study and previous two meta-analyses was shown in Table 3. Although, this meta-analysis is the largest study published in the literature currently, the results should be interpreted in caution. First, 2 of the 11 studies were available as conference abstract and therefore, lacked full methodology.22,23 Consequently, we could not do quality assessment for trail bias. This might be contributed for the heterogeneity of some of the endpoint parameters. Second, due to lack of data, we couldn't do subgroup analysis in no nausea endpoints as many as in no vomiting endpoints. Therefore, the effect of olanzapine in preventing nausea could be underestimated. Third, due to lack of additional trail since the work of Chiu and colleagues34, we are an able to do meta-analysis on effect of olanzapine on breakthrough CINV. Finally, it was not possible to do meta-analysis on safety endpoints as some of the trials reported MD Anderson symptom Inventory (MDASI) score and the others reported as either not important or not reported it all. Hence, it is mandatory to do well design trial to assess the safety profile of olanzapine in preventing and treatment of CINV.

CONCLUSIONS

Olanzapine containing regimen was both statistically and clinically superior to non-olanzapine regimen in preventing CINV in patients receiving highly emetogenic or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. It remained vague whether olanzapine should be used with NK-1 antagonist or as alternative. Therefore, it is uncertain whether these results will change the current standards of antiemetic practice. The weight is towards use of combination of olanzapine with dexamethasone until convincing evidence will be available. In general, it seems that there is paucity of strong evidence to change the current practice of antiemetic therapy in preventing VINV. Hence, we recommend large RCT or cohort study that identifies the use of olanzapine in steady or in combination of NK-1 antagonists with economical evaluation.