INTRODUCTION

Community pharmacists have a broad ranging remit and face various challenges in their everyday role. They contribute to patients’ care by dispensing medicines safely and in a timely manner, in order to optimise medicines use and improve health outcomes.1 Pharmacists offer in their daily practice a comprehensive package of services and support to patients. This is mostly achieved through ad hoc conversations or more formal consultations. Counselling remains a challenge as within a short period of time, the pharmacist should take an appropriate history and provide relevant advice. Both nationally and internationally, the role and responsibilities of community pharmacists have been changing to use specialised knowledge and clinical tasks2 for the purpose of optimising patients’ use of medicines. The recent change of paradigm from a paternalistic way of giving advice to a passive and silent patient, toward empowering and involving them into the treatment, requires new skills. The implementation of so-called pharmaceutical cognitive services3 is independent of pharmacy systems and health care structures across countries.

A prerequisite to pharmaceutical cognitive services is an effective dialogue during patient-pharmacist interaction. A lot has been published to instil Good Communication Practice into healthcare professionals4-6 that mostly ends up with precepts such as a patient-centred approach4, individualised medicine advice7, tailored to the person’s context and experiences7, and delivered in a personalised way.8 However, how to transform the skill into a verbal interaction with the patient represents the core competency. The importance of how a question is asked has been recognised since years.9

A framework has been developed10 to guide pharmacists during medication-related consultation. It can be used as semi-structured interview guide to obtain and give information in a two-way communication.11 However, during daily routine, prompt cards and reminders are often preferred9 because they indicate how questions should be asked or they represent basic information that should be captured in any case. Further, they might represent an essential approach when performing counselling, independently of the degree of experience of the pharmacists. To our knowledge, content of pharmacist-led counselling is poorly investigated12 and communication tools used by the pharmacists are unknown. We developed a prompt card and asked participants to use it 10% of their consultations with patients on anticoagulants because these are high risk medicines, and new products have come onto the market (non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants, NOACs) for which a high adherence is needed to reduce patient risk.13

The aim of this study is to evaluate in practice a pharmacist’s prompt card developed to support effective patient consultation, with an emphasis on anticoagulated patients. The participants were purposively selected and commissioned for the market research from a group of pharmacists by MH Associates who undertook the study. Pharmacists consented to give their personal views and considerations regarding routine counselling of patients. No patient-specific data was collected hence ethics approval was not required.

METHODS

Development of the instruments used

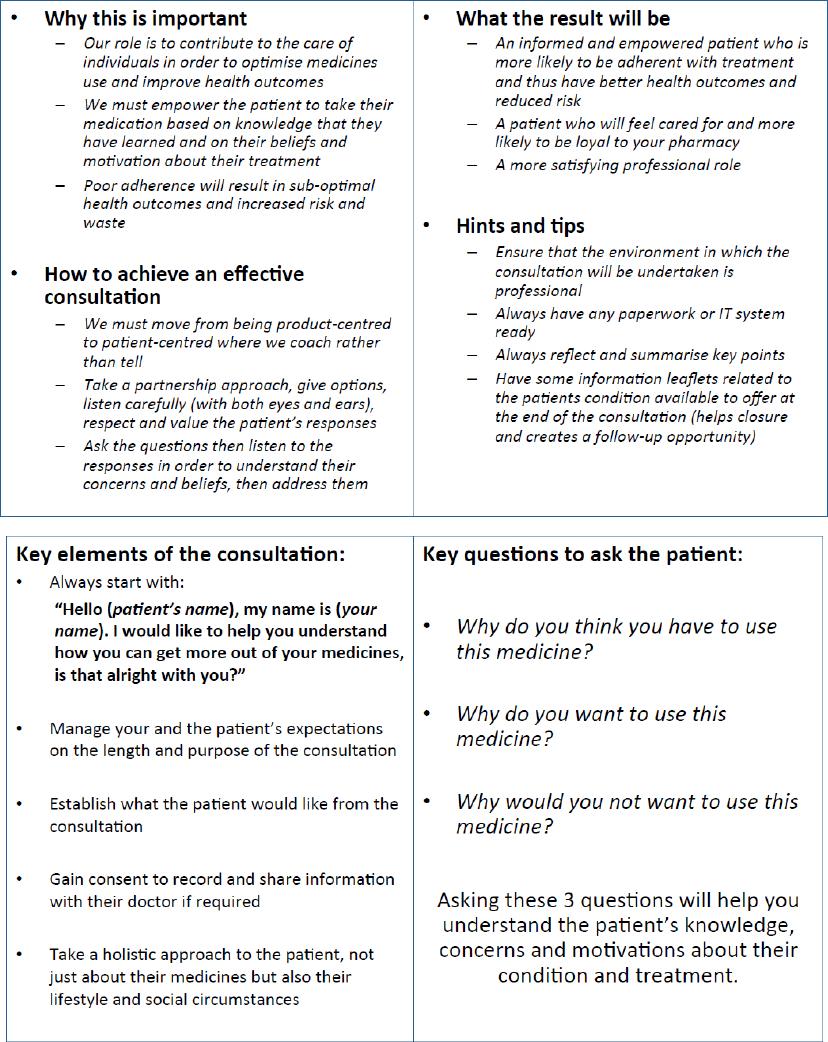

The prompt card (see Figure 1) was developed as a double-sided, post-card format tool. One side aims at giving a sense of responsibility to the pharmacist through background statements that remind them of the advantages of empowering patients to take their medicine. Slogans and 4 general statements were adapted from published recommendations.11,14,15

On the other side, 5 key elements (left half of the card) remind to start a consultation by introducing oneself; to indicate the length and purpose of the consultation; to establish what the patient would like from the consultation; to gain consent to record and share information with their doctor; to take a holistic approach to the patient’s lifestyle and social circumstances. These elements were adapted from postgraduate education program on consultation skills.16

Three formulated key questions (right half of the card) were developed to lead the pharmacist to understand the patient’s knowledge (“Why do you think you have to use this medicine?”), motivation (“Why do you want to use this medicine?”), and concerns (“Why would you not want to use this medicine?”) about their condition and treatment. These elements were developed based on the concept of “Start with why” to change human behaviour17 and have never been used in the past. The key questions address the critical phases of initiation and persistence of therapy18 and not the implementation (such as intake with food; twice daily 12h apart; on an empty stomach etc.).

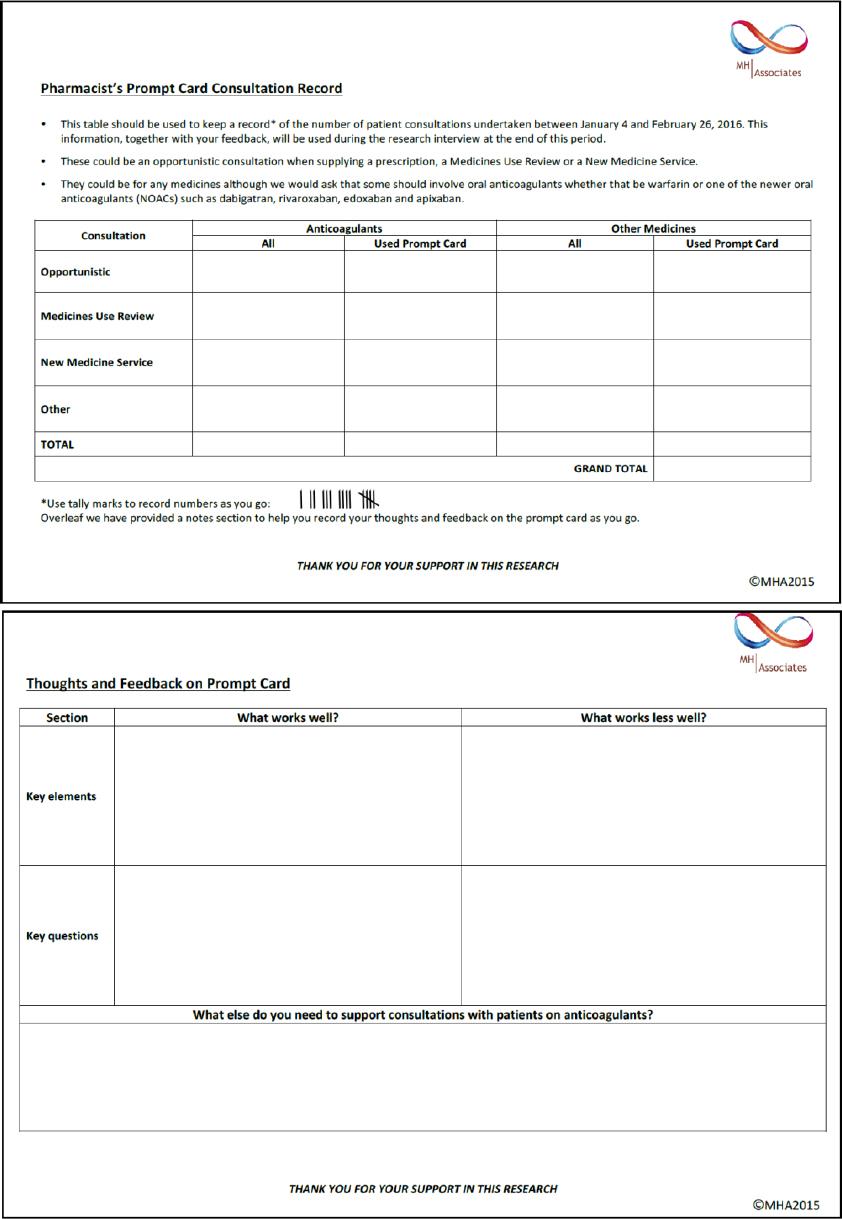

A consultation record card was developed and given to the participating pharmacists (see Figure 2). Thoughts and feedbacks concerning the key elements and the key questions could be noted on the back of the card.

Study design and setting

This was an exploratory study performed in community pharmacies in North of England. Independent community pharmacists who were already engaged in delivering Medicine Use Review (MUR) and New Medicine Service (NMS) were invited by a personal letter to participate in the research aimed to test and validate the prompt card. They were provided with prompt cards and consultation record cards, and were asked to use the prompt card in consultations during the period 4th January 2016 to 26th February 2016. Patients’ inclusion criteria were left at the pharmacists’ discretion but should justify an opportunistic consultation (i.e., when supplying a prescription), a NMS or a MUR, for any medication. One in tenth consultations should involve any oral anticoagulant (warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban and apixaban). Pharmacists were asked to record the total number of consultations and to note the number of times the prompt card was used.

Telephone interviews were conducted with the pharmacists during the period 4th March to 16th March 2016 using a professional market researcher. A qualitative in-depth methodology was used. In brief, loosely structured interviews of 30 minutes duration in the form of a guided conversation with a pre-determined set of questions were carried out to explore subjective viewpoints, personal experiences and any learning with elements of the prompt card. Follow-up questions were allowed to further clarify a participant’s answer, if needed. Participants were asked to rate usefulness of the prompt card on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 being not at all useful and 7 being extremely useful.

Data analysis

We used a mixed-methods approach with sequential strategy where the quantitative phase (i.e., use of the prompt card during counselling) informed the following qualitative phase (i.e., telephone interviews). For descriptive statistics, we reported percentage and mean values with standard deviation and range, where appropriate. Qualitative data from the telephone interviews and written statements from the consultation record cards were coded and summarised in thematic categories and subcategories using deductive content analysis.19

RESULTS

Of the 30 pharmacists invited to participate, 20 accepted and 19 completed the study (66% response). They were on average 36.6 (SD=9.0) years old, mainly men (63.2%) and pharmacy managers (68.4%). They were qualified pharmacists of 12.9 (SD=9.8) years of experience on average (range: 2-34 years) and performed MURs since an average of 7.3 (SD=3.1) years (range 2-10 years), with a post-graduate qualification for eight of them (clinical diploma (7), one independent prescriber). All worked >20 hours in independent pharmacies (13 medium sized, 4 large and 2 small sized) and located in suburban areas (7), health centres (6) or high street (6).

Over the 8-weeks study period, a total of 1,034 consultations were performed, mostly MURs (62.2%), of which 12.8% were anticoagulant consultations. Any reminder was used 497 times, the prompt card was used 104 times during anticoagulation counselling (10%; see Table 1). Three pharmacists did not use the study prompt card and one pharmacist exclusively performed brief ad hoc consultations. All pharmacists were interviewed.

Table 1. Number and type of consultations performed by the 19 community pharmacists enrolled in the study, with number of prompt cards used during anticoagulant consultation.

| Consultation type | MUR | NMS | opportunistic | other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 643 | 308 | 60 | 23 | 1,034 |

| anticoagulant | 57 (8.9%) | 50 (16.2%) | 23 (38.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | 132 (12.8%) |

| other medication | 586 (91.1) | 258 (83.8%) | 37 (61.7%) | 21 (91.3%) | 902 (87.2%) |

| Use of a reminder | 318 | 140 | 35 | 4 | 497 (48%) |

| prompt card during anticoagulant consultation | 49 (15.4%) | 37 (26.4%) | 16 (45.7%) | 2 (50%) | 104 (10%) |

| other reminder | 269 (84.6%) | 103 (73.6%) | 19 (54.3%) | 2 (50%) | 393 (38%) |

MUR: medicines use review; NMS: new medicine service; opportunistic: when supplying a prescription; other: shorter consultation within a different contract.

Overall views on the prompt card

There was agreement that the card acts as a useful reminder to cover all points that should be addressed in a consultation (“It makes sure that patients say what they need to, and that you provide all the information that is necessary”). The main key advantages were the concise form, the completeness (“Makes sure cover all bits you should”) and the value of the questions (“Not something that we always ask”). Even when pharmacists have significant experience with consultations and may have developed their own style, the card helped to keep consultations focused and on track (“old dog new tricks”, “Helps to keep / bring back to key focus of conversation”). There was a feeling that the card would be more valuable for less experienced pharmacists and those with less confidence engaging in conversations with patients (“For those that don’t want to / find it hard to talk to patients”; “It will be particularly useful to newly qualified pharmacists who are looking for something to get themselves into the way of doing stuff”). However, there was some resistance to having to read off a prompt card in a face to face consultation (“You could look like you don’t have the knowledge if you keep looking down at the prompt card”; “The idea of a card is reasonably useful if I’ve got a telephone conversation taking place”).

Background statements

The information included in this section was commented on positively (“Empowering the patient, patient centred care, these are buzzwords that the NHS is using at the moment. It’s very helpful”; “I would be surprised if people don’t know this, but they might not practice it”). However, there was mention that some additional education or information is needed about how best utilise and to implement the card approach (“It says manage your and the patients expectations about the consultation - how?”). However, there was some acknowledgement that with experience of using the card, pharmacists would become familiar with the approach and be able to adapt the concept to individual patient and consultation scenarios (“Once you have used it long enough you would probably be able to do it out of memory”).

Five key elements

1. Start: The personal introduction was recognised as extremely important to start the consultation to let the patient know who the pharmacist is, and that the pharmacist is aware of the patient’s name. It puts the patient at ease and begins to build rapport (“This is empowering the patient and asking patient’s permission, involving them rather than just giving all the advice whether they like it or not”; “To be honest, ‘is this alright with you?’ is a fantastic way of gaining agreement that this consultation is worthwhile and can be carried out”). Participants did not use the phrase “I would like you to get more out of your medicines” but adapted the introduction to fit the purpose of the consultation. For example, if they were undertaking an MUR, they would explain briefly what that covered (“Hello I’m... we are just going to run through your medicines to see how you are taking them and to see if you have any problems”). There was consensus that the introduction should explain the purpose of the consultation, certainly for consultations where patients are being taken into the consultation room. Patients can become concerned when the pharmacist proactively asks to speak to them, so there is need to provide reassurance that there is nothing to worry about.

2. Length and purpose: Participants indicated that it was relevant to provide the patient with some idea about how long the consultation was likely to last, especially because patients do not want to spend a long time in a consultation. For several participants, it was a revelation (“The 2nd point is brilliant, it gives them an idea of how long a consultation is going to take so they don’t go over time as well, the staff don’t interrupt me, they now know it will be 5 to 10 minutes, and they can tell patients that are waiting how long I will be”). Informing patients increases their willingness to participate in any pharmacist initiated consultations (“I guess it encourages them to think it’s worthwhile without taking too much time”).

3. Establish what patients want: This question was more relevant if a patient initiated a consultation, since most patients do not specifically want something out of the consultation. There was a general feeling that the question provided more an opportunity for patients to contribute their views about their medicines, ask questions about their conditions, and discuss any other health related issues (“It can be a bit rude saying what do you want today, it’s more about how can I help and listening to them”). There was feeling that this element needs additional explanation and practical examples of how to incorporate it into a consultation (“I find it better to run through things and then to ask them if there is anything else they would like to ask or talk about”).

4. Doctor consent: There was overall agreement that this is part of the process when undertaking an MUR or NMS consultation. Pharmacists would require this in ad hoc consultations should it become appropriate (“Today I was speaking to a gentleman and I asked ‘would you like me to write to your GP to do that’, and he said ‘yes please’. I told him that I needed his permission to speak to the GP on his behalf”). The only debate was that some pharmacists gain consent at the beginning of a consultation whereas others do it at the end. There was consensus on explaining why the pharmacists would need this.

5. Holistic approach: Although relevant holistic topics (diet, lifestyle, weight, smoking cessation) are addressed in MUR/NMS consultations, participants agreed that it is massively important to broaden out the conversation in order to optimise the value of the consultations (“The patient is getting a better experience because they are being treated as a whole person rather than just a list of medications”). There was agreement that taking a holistic approach has many benefits including patient centeredness, adding to good reputation, and getting better connection with the patient. The only downside mentioned in terms of taking a holistic approach, was lack of time (“It would be lovely to be able to do all the healthcare advice but it’s not always top of the agenda”).

Three key questions

The participants agreed that the open questions were useful and would work well. They felt they would be able to adapt the questioning in terms of how the conversation was going during the consultation, and add additional questions. In this regard, many felt there was a need to include a specific question about “how patients are taking their medicines” on the prompt card. This would enable the pharmacists to understand if medicines were being taken correctly and if not, to provide information and rationale for adhering consistently to the recommended regimen (“You want to build up a picture about how they feel about their medicines and how they are taking them to ensure they are getting the best use”).

1. Why use medicine: The participants effectively used this question in their consultations, and found it relevant and valuable (“Good opener”). Overall, the phrasing worked well (“You get a genuine answer about what they think they are taking their medicines for”). The general sense was that the question provides a logical and user friendly way for pharmacists to gain an understanding about patient’s knowledge of their medicine. (“That’s important in terms of the modern approach to patients, it’s patient led. Rather than just being told to take this tablet, it’s more about the patient understanding why”). The response from the patient then enables the pharmacist to correct any misunderstandings, and also to provide additional information about the medicine (“We can clarify more why they should be taking it”). One participant felt the question may work less well in an MUR situation as it would be repetitive when asking for every medicine the patient is taking.

2. Why want to use medicine: The participants commented on this question negatively, and most abandoned using it during the trial period. Fundamentally, it added no value to consultations (“Most people just said it’s because the doctor has told me to use it”). When asked for suggestions of what would be more relevant to include in a consultation, most pharmacists focused on a question to determine what benefits a patient expected to gain from taking their medicine (“What do you think are the personal benefits of taking that medicine?”).

3. Why not want to use medicine: Although participants understood what was attempting to elicit from patients in terms of any concerns about their medicines, many were not comfortable using the wording of the question. This question generated negative responses, and could lead to patients questioning the value or safety of their medicine (“This leads into problems with medication, side effects, tablets not working, stigma, image”). However, there was a view that getting information around any problems or concerns is important during a consultation. It allows pharmacists to provide reassurance or offer solutions, with the ultimate goal being to stress how important it is to take medicines as prescribed (“You can then question them further and find out what is worrying them and then see if you can actually improve their outcomes and try to sort it out for them”).

Rating usefulness and potential use of the prompt card

The prompt card was estimated as quite useful with most pharmacists rating either 4 or 5 (median 4.5; range 2-7). The most valuable reasons cited were “a good aide memoire”, “reinforces what should be doing”, and “sets out best way to undertake consultation”. The less useful reasons cited were “don’t want to hold / read off the card”.

Use of the prompt card with anticoagulated patients

As an MUR and NMS target group, anticoagulated patients are clearly important. The pharmacists did not mention any specific difficulties when using the prompt cards with patients taking anticoagulants. One participant emphasised the absence of concordance on the card, and if this was deliberate, as this was part of his consultation with anticoagulant patients. The participants commented that communication skills specific to anticoagulant patients would be useful, mainly for the most experienced pharmacists as refresher (“How about a consultation technique specific to anticoagulant patients? A checklist of what you need to consider and what you need to look out for”). Importantly, there was significant discussion about the need for patient focused information and leaflets, with some feeling that these would be useful tools for pharmacists to have access to, and would potentially reinforce key points about anticoagulants for patients (“The newer anticoagulants haven’t been out that long, so I’m kind of OK with those, but obviously if anything changes we need to be kept up to date”).

DISCUSSION

Adoption of the new skills required for the dispensing of cognitive pharmaceutical services (e.g., “Take a partnership approach”) has been slow20, and barriers concern predominantly the communication.21 In this context, to raise the pharmacists’ awareness by means of describing the new skills seems necessary and was approved by our participants. Even though the recruited pharmacists were accredited and used to perform consultations, the background statements on one side of our prompt card were clearly judged relevant.

The prompt card acted as a checklist and reassured that they did not miss any key point during the consultation. Moreover, the explicit questions were highly appreciated since one barrier to counselling is often the lack of knowledge of which questions to ask patients9 or using self-developed questions that had been judged adequate over time, however doubts raised about whether a different phrasing might be better. Thus, our study highlighted the accuracy of 5 key elements. The specific phrasing for starting the consultation “Hello, my name is... I would like to [define the purpose of the consultation] and help you understand your medicines, is that alright with you?” was highly appreciated. Even if the introduction to consultation has been promulgated for years as a way to start consultations with patients, for example with the framework Situation - Background - Assessment - Recommendation (SBAR), using pre-formulated wordings may sometimes be challenging. Thus, our starting question seems to create rapport and obtain first active approval from the patient.

Although developed as open questions, only the 1st key question (“Why do you think you have to use this medicine?”) worked very well to open the discussion, and to gain an understanding about patient’s knowledge of their medicine in a friendly manner. The aim of the 2nd question, i.e., to assess a patient’s perceived necessity to use the medicine (“Why do you want to use this medicine?”) was not recognised by the pharmacists or the patients, probably because the underlying concept is not obviously phrased. The aim of the 3rd question, i.e., to assess a patient’s perceived concerns to use the medicine (“Why would you not want to use this medicine?”) was recognised by the pharmacists, but the phrasing was misunderstood by patients as appealing to potential issues with the medicine, instead of personal behavioural statements. Both questions need rephrasing, probably with the explicit use of the terms ‘necessity’ and ‘concerns’ to target personal statements.

One of the barriers to use the prompt card was that reading sentences from a card made the pharmacists feel uncomfortable. However, studies about pharmacists looking into a computer placed at the point of sale (e.g., while seeking for information or entering data in a system) demonstrated that this action did not negatively affected the relationship between patient and the health care professional.22 When paperwork for personal notes or information leaflets are present in the counselling room, the presence of the prompt card can be discrete and unnoticed by the patient.

We acknowledge some limitations. First, we did not assess how the pharmacists perceived that the communication based on the prompt card adds to (or differ from) the way they usually communicate. However, the specific elements of the prompt card have been assessed and a revised version can now be designed, whose effect on the pharmacist’s communication can be tested. Second, the quality of the present study depends on the motivation (quantitative phase) and the answers (qualitative phase) of the participants. The data show consistency and saturation, but different results might have been obtained with different participants. Nevertheless, the purposive sampling of accredited and highly motivated pharmacists should have restricted this limitation.

CONCLUSIONS

Our prompt card offers a logical framework to guide the overall approach when undertaking a consultation. It proposes explicit phrasing (e.g., “is that alright with you?”) and is indicated during the phases of introduction and data collection / problem identification. However, of the 8 proposed elements and questions, two need rephrasing and an additional question is needed to determine how patients are using their medicines. We will develop and test a revised version of the prompt card.