CHILEAN HEALTHCARE SYSTEM AND PRIMARY CARE

Chile is a country of 17.5 million people, composed of 16 regional governments, and 349 local governments called municipalities.1 Chile’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for 2019 was USD 14,896.2 Chile is a member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and is classified as a high-income country but has a very high inequality index (Gini coefficient of 0.46).3 Twenty percent of the country’s population earns 51.3% of the GDP.2 In 2019 Chile spent USD 2,159 per capita or 9.1% of its GDP in healthcare, which is about half the OECD average of USD 4,224 per capita. Of this spending, 34% were out-of-pocket payments made by patients, the third largest of the OECD.3

The Chilean healthcare system is a two-tier system with a public and private sector. Chileans are mandated to pay 7% of their salaries for health insurance (except for retired older adults who continue working) with an option to choose either public or private health cover.4 Private health companies [Instituciones de Salud Previsional] (ISAPRESs) cover 19.6% of the population but receive about 54% of health funding.5 These private companies tend to cover younger men with higher income driven by unregulated premiums that discriminate by sex and age.5 Eighty percent of the citizens are covered by the public national health fund [Fondo Nacional de Salud] (FONASA) including high-risk groups that use more resources posing an increased burden.5-6 In 2006, the government implemented the Explicit Health Guarantees System [Garantías Explícitas en Salud] (GES). GES is a group of enforceable benefits for FONASA and ISAPREs beneficiaries. Their main objective is to ensure timely access to healthcare while protecting the extent of the population out of pocket expenditure. Currently, GES covers 85 conditions.6-7 Nonetheless, conditions that are not covered by GES have long waiting times, and usually will require high out-of-pocket payments. An additional program was introduced in 2015 to avoid catastrophic health expenses by covering high-cost rare diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Huntington’s disease.8

Most patients insured by ISAPREs use private providers for primary, secondary and hospital care. Their focus is on treatment of diseases, with little incentive to perform health prevention activities.5 In contrast, the public system has its own infrastructure and is mandated by the Ministry of Health. The public health sector is coordinated by the sub secretariat of Assistance Networks of the Ministry of Health, regulating and supervising healthcare services.9 This sub secretariat coordinates the National System of Health Services, or 29 autonomous administrators that oversee their local network of primary and secondary care, as well as emergency and hospital treatment.9 From 2004, the main objective of the Ministry of Health has been to build a healthcare model based on primary care, emphasizing population health, and focusing on health promotion and prevention, following the guidelines for Sustainable Development Goals of the World Health Organization (WHO).10,11

In Chile, public primary care is mostly overseen by each Municipality (346 local governments) with 10% being managed directly by the local health care service administrator. These primary care centers are divided by size as small (rural health posts, 4,000 average population), medium (community health centers, 8,000 average population) and large (family health centers, 20,000 average population).12 These centers are organized using the family medicine model, proposed by WHO, with a multi-professional practice that encompasses not only the patient, but the family and the community.13 Centers are composed of one or several multidisciplinary teams (depending on size of the center) that provide healthcare for a geographically defined population. Family health centers [Centro de Salud Familiar] (CESFAM) are the larger providers of local primary care and also coordinate the smaller centers in their territories. Healthcare teams are composed by health professionals, including physicians, registered nurses, dietitians, psychologists, dentists, physiotherapists, and midwives. Other professionals such as social workers, speech therapists and pharmacists are not part of the core teams but are present in some centers.14

Interventions performed by these healthcare teams must encompass promotion, prevention, recovery, and rehabilitation actions over the lifespan of the individual. To carry out these actions, primary care has dual funding system, with a per capita system as well as a pay-for-performance scheme.14 The per capita system is the main source of funding, and covers most health services, medications and personnel for each center based on the assigned geographic population. In the pay-for-performance scheme or primary care reinforcement program, specific interventions such as respiratory health care, dental care and dispensing of chronic medications receive additional funding depending on some health outcomes and the number of patients’ visits and health checks. Additional remuneration is provided when predefined goals are achieved.14 Both schemes are determined by the Ministry of Health, while the latter scheme is used as a leverage to encourage primary care providers to engage with public health objectives, including effective collaboration with other levels of care.15

MEDICATION ACCESS IN PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

In 2019 Chile had the highest price for original branded medicines in the Latin American region, with USD 14.1 per unit. In contrast, generics prices were one of the lowest with USD 1.30 per unit. Generics represented only 48% of total sold units for prescription medicines.16 As a consequence, medications are more than 50% of out-of-pocket payments in Chile, influencing the use of chronic medicines.3

Patients from ISAPREs must purchase their medicines from privately owned community pharmacies. For some chronic conditions, following the GES policy, ISAPREs cover part or all the out-of-pocket payments of some medications (15 to 35% for original medications and >80% for generics). This occurs only if the patients attends an approved healthcare provider and has the prescriptions dispensed in certain specifically contracted community pharmacies (mostly chain companies).7 Patients can pay for additional medication coverage (up to 80%) on their ISAPREs or from another insurance company, but this does not include all medicines, and patients are still required to attend certain contracted pharmacies. There is also an annual cap.5

Patients that belong to FONASA receive their medications free of charge in state owned pharmacies embedded in each public health center. These pharmacies have limited availability of chronic and acute medications depending on the level of healthcare provided in the establishment. Physicians are encouraged to prescribe these specific medications.6

To reduce out-of-pocket payments and improve medication accessibility, publicly owned pharmacies have programs that guarantee most chronic medications for FONASA users: The Ministry program and the Pharmacy Funds program [Fondo de Farmacia] (FOFAR) and both provide additional funding to avoid supply issues.6 In the Ministry program, the primary care division of the ministry of health buys and distribute to each health service coordinator or municipality all medications covered by FONASA for epilepsy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, osteoarthritis, depression, Parkinson’s disease, hypothyroidism, insulin for type-2 diabetes mellitus, and contraception. FOFAR includes additional funding for the treatment of hypertension, type-2 diabetes and dyslipidemias.19 However, it is not uncommon that patients must buy a proportion of their medicines in community pharmacies, as public pharmacies usually have shortages on medicines not included by these programs and/or have outdated medications.20 In 2019 FONASA implemented a coverage program for these patients (12% to 30% of discounts) in a small number of selected community pharmacies, but it has low implementation and only in a reduced list of medicines.21

To reduce out-of-pocket payments in medications, a non-profit model of pharmacies, called municipal or solidary pharmacies, were created by some municipalities in 2015, providing medications at almost cost-prices to their population. In 2020 there are more than 160 municipal pharmacies, with their prices being at least 50% lower than privately owned community pharmacies.21

COMMUNITY PHARMACIES AND PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES

In 2019 there were 3,818 community pharmacies, including municipal pharmacies, in Chile, with almost half of them belonging to three chain pharmacy companies. These chain pharmacies represent more than 90% of the national market and are mostly located in urban areas, as there are no geographic restrictions for opening pharmacies in Chile. The rest of community pharmacies are mostly small or medium businesses that are evenly distributed over the country. Interestingly there are 54 small municipalities in Chile that do not have a community pharmacy on their territories, and municipal pharmacies have been proposed as a solution to this lack of medication access.21

There is no obligation for pharmacy owners to be pharmacists, however, since 1984 the employment of pharmacists during operating hours is mandatory, and they must be available for patient counselling, prescription supervising and dispensing of certain medications. Since 2015, the legislation identified community pharmacies as healthcare centers, guaranteeing the rational use of medicines and providing pharmacovigilance services.22 However, the role of these community pharmacists is mostly in management, with little to no direct contact with patients and with pharmacy technicians performing most of medication dispensing. Community pharmacists are often described as ‘behind-the-counter professionals’ with a minor health role, especially in chain pharmacies. On the other hand, smaller pharmacies usually provide some patient counselling, but their market share is low and as these services are not funded, so it is not prioritized.23

Community pharmacies, especially those owned by the chain companies, have a negative public perception.24 In 1995 and 2008 the three main chain pharmacies were found guilty of collusion due to price-fixing of several products.25-26 The companies were penalized with a fine of USD 60 million as compensation.25-26 As prices of medications continue to increase, Chilean consumers are reported to have one of the worst opinion of pharmacies and the pharmaceutical industry in the Latin American region.24

Interestingly, one of the chain pharmacies between 2003 and 2005 developed a pharmaceutical care program, with pharmacists providing medication reviews to chronic patients. The service was free of charge, and patients signed up voluntarily at their local chain pharmacy. A randomized-controlled trial of 6 months duration was conducted in 2003 to evaluate the program, finding a statistically significant reduction on lipid levels.16 Nevertheless, the program was discontinued in 2005.

There is a perception that most small privately owned and publicly owned municipal pharmacies provide patient counselling and other services, however, there has been no evaluation and these services are also not standardized.

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE SYSTEM AND PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES

The presence of pharmacists in the primary care network has been historically low. Prior to 2014 (and FOFAR), a small team of pharmacists from each of the 29 autonomous health services coordinators remotely supervised the public primary care pharmacies in their territories. As there was no legal obligation to employ pharmacists, less than 10% of the primary care centers had a full-time pharmacist. Since 2014, FOFAR has included funds to employ pharmacist in the larger primary care centers, reaching more than 100 by 2016.14 These pharmacists were used mostly for management functions, but some of them have started to provide clinical services at their own initiative or by requests from local clinical teams.

Because of the increasing number of pharmacists and growing interest from health centers and the Ministry of Health, a 6-months randomized controlled trial was conducted in 2016 in the largest primary care center in Chile to explore the impact of medication reviews with follow-up on 212 cardiovascular older patients. The study provided initial evidence that pharmacists could significantly improve the control of hypertension, type-2 diabetes and dyslipidemias in the Chilean primary care setting.27 The Ministry of Health, responding to these results, added pharmacists to the 2017 national cardiovascular care program guidelines, stating that where available, pharmacists should participate in clinical teams providing services for cardiovascular patients. These guidelines were the first in Chile to include pharmacists in primary health care teams.28

Following this study, a cluster randomized controlled study, the Polaris trial, was conducted between 2018 and 2019 to provide further evidence on clinical and economic outcomes of the inclusion of pharmacists in primary care teams. The results provided evidence that the intervention, a comprehensive medication review with follow up, was a cost-effective addition to control cardiovascular risk factors. After the Polaris trial, and as more clinical guidelines included pharmacists in 2018 and 2019, the Ministry has been increasing the number of full-time pharmacists in primary care centers, reaching more than 450 or >80% of the largest centers in 2020.14

Prior to 2018, there were only two pharmaceutical services defined in the official national registry determined by the Ministry: pharmacovigilance services and pharmaceutical care. As the provision of pharmaceutical services grew, this registry was not sufficient to describe all of pharmacists’ actions taking into account that primary care pharmacists have access to all clinical information of their patients. In 2019, major modifications were made. An official list of pharmaceutical services, with some of them using the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) classification for medication reviews, was published (see Table 1).29

Table 1. Official pharmaceutical services for the public primary health care network

| Pharmaceutical service | Description | Patient-per-hour rates |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical services | ||

| Medication review without visit (type 2b or intermediate by PCNE) | Pharmacists conduct medication reviews using all information available in official medical records and pharmacological prescriptions. Pharmacists would add their findings and suggestions to the medical records to be considered by physicians. | 4 - 6 PPH |

| Medication review with visit (type 3 or advanced by PCNE) | A one-or-twice yearly visit added to the previous service to detect nonadherence motives and include additional patient’s information. | 3 - 4 PPH |

| Medication review with follow-up (type 3 or advanced by PCNE) | A systematic, structured service using the Polaris method as guideline. The service consists in at least three visits with the patient (initial, intervention and follow-up). The pharmacist meets with the physician after the initial visit to discuss the findings and suggest pharmacotherapy modifications if needed. Any agreed intervention would be directly implemented and registered by the pharmacist in the next visit, depending on the patient’s acceptance. The pharmacist would monitor the results of the interventions in follow-ups and perform the service until every health problem is resolved, if the patient does not want to continue or if the pharmacist discharges the patient. | 2 PPH for initial visit 3 PPH for follow-ups |

| Individual education | Pharmacists implement educational programs to increase patient’s knowledge and health literacy. This program would be comprehensive, adapting to the patient’s needs and in agreed topics. | 3 - 4 PPH |

| Pharmacovigilance | Detection, report and solving of adverse drug reactions. | 4 - 6 PPH |

| Medication reconciliation | A simplified review of the medications conducted when a patient changes their level or site of care (e.g. hospital to primary care or private to public system) to prevent therapeutic duplicities and omissions. | 6 - 12 PPH |

| Group education | A group session where the pharmacist carries out a Flexible activity according to the group of patients’ needs and the educational objective. Pharmacists can implement group education in subjects such as the use of medicines, medication adherence, medicinal herbs, and others. The pharmacist can also contribute to group educations organized by other professionals. | 2 PPH |

| Home visit | Pharmacists provide pharmaceutical services at the patient’s home. This service is reserved for dependent patients and their caregivers. | 1 PPH |

| Non-clinical services | ||

| Medication quality control | Pharmacists must report to the health authorities when medication quality issues are detected in the health center, sending samples to be analyzed. | -- |

| Adverse drug events | Pharmacists must report and resolve adverse drug events that occur in the health center. | -- |

PCNE: Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe; PPH: patient-per-hour.

Despite the inclusion of these services on the list of official clinical activities for the primary care network, most pharmacists are unable to provide them, as they are predominantly focused on management tasks. This was observed and reported in the Polaris trial and has been reported by the international literature as one of the main barriers for the implementation of pharmaceutical services.30

In 2020 the Ministry of Health implemented a multimorbidity care model in some primary care centers. This is a health stratification model. It uses the number of chronic conditions (from an official list of more than 50 diseases) and socioeconomic and psychosocial factors, which are then used as risk scores. Some health conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, severe kidney disease and dementia are defined as ‘critical’ and provide double scoring. Patients are then classified as healthy or having a null risk (score 0), low risk (score 1), intermediate risk (score 2 to 4) and high risk (score ≥5), and health services are provided depending on each patient classification. The Ministry is employing more professionals, including part-time pharmacists, to support the implementation of multimorbidity care, and it is planned that all the primary care networks will use this model by 2030. Pharmacists are expected to provide pharmaceutical services to the higher-risk patients, but the nature and details of these services have not been defined.31

In contrast, the private primary care network does not provide pharmaceutical services, as they are not funded by ISAPREs. FONASA is commonly used as reference by private companies for service coverage, but pharmaceutical services have not received a specific codification or pricing.7

PHARMACIST TRAINING AND PROFESSIONAL REPRESENTATION

In Chile, to be a pharmacist one must complete a 10-to-11 semester academic program. There are currently 17 pharmacy schools. The academic level of a pharmacy degree is at a level between a bachelor and a master’s degree if compared to international standards (‘professional’ level in Chile). More than 50% of these programs consist of basic science training such as chemistry and biology. Health-related subjects are scarce and represent less than 10% of the programs. Furthermore, most pharmacy schools do not provide training on interviewing skills, and pharmacists usually lack the abilities and experience needed to provide patient counselling.23

As a response to a need for pharmacists with clinical skills in the hospital healthcare system, the Ministry of Health approved a specialist clinical pharmacist program in 2018, recognizing that additional training was required for this level of care.32 It is a two-year program and is being provided only by two pharmacy schools in 2020, with a quota of less than 10 graduates every year. From 2021, the ministry will require a 3-year program. In 2020, there are still less than 100 clinical pharmacy specialists in Chile. Nevertheless, the employment of these specialists is funded only for hospital care. Some universities have developed additional postgraduate courses for ambulatory pharmacists, and these are increasingly being funded by public entities to incentivize the provision of pharmaceutical services in primary care centers.

After graduating, pharmacist can pay a monthly fee to join the Chilean Pharmacists Association [Colegio de Químicos Farmacéuticos y Bioquímicos de Chile]. The role of this organisation is primarily political advocacy and does not receive funding from the government. About 10% of pharmacists in Chile belong to the Association. The Pharmacists Association represents pharmacists on government committees and is usually invited to participate as a stakeholder. However, as most pharmacists are not part of the Pharmacists Association, it has a limited influence. There are a number of smaller independent organizations focused on segments such as the pharmaceutical industry, community pharmacies and some scientific associations for primary or hospital care pharmacists. They often play a similar role to the Association.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES IN CHILE

Chilean pharmacy program and the Pharmacists Association

The pharmacy programs should be modified to reinforce clinical skills from the initial undergraduate years, as these competencies must be developed over time. We understand that pharmacists can work in very different areas and they require a wide scope of skills, but Chilean healthcare system is requiring more clinical involvement. The international literature supports the provision of pharmaceutical care.33 Training should provide direct contact with patients at different levels (hospital and ambulatory care), and pharmacists should be able to provide clinical services such as basic or intermediate medication reviews, pharmacovigilance services and patient counselling without additional postgraduate courses.

As for the Pharmacists Association, its role should be expanded to provide more than political advocacy and representation of the pharmaceutical profession. The Pharmacists Association should influence pharmacy undergraduate and postgraduate programs, establishing and certifying professional standards for all pharmacy segments, as well as participating in developing policies related to medicines. The Pharmacists Association should also negotiate medication coverage, provision of pharmaceutical services and pharmacists’ involvement in the health care system. It could provide guidance to the government and generate evidence related to the efficiency and effectiveness of pharmaceutical services, as is the case in other countries such as Australia, Canada, and Spain. To accompany and support this expanded role, Association membership should be mandatory for all pharmacists.

Opportunities to further develop pharmaceutical services in primary health care

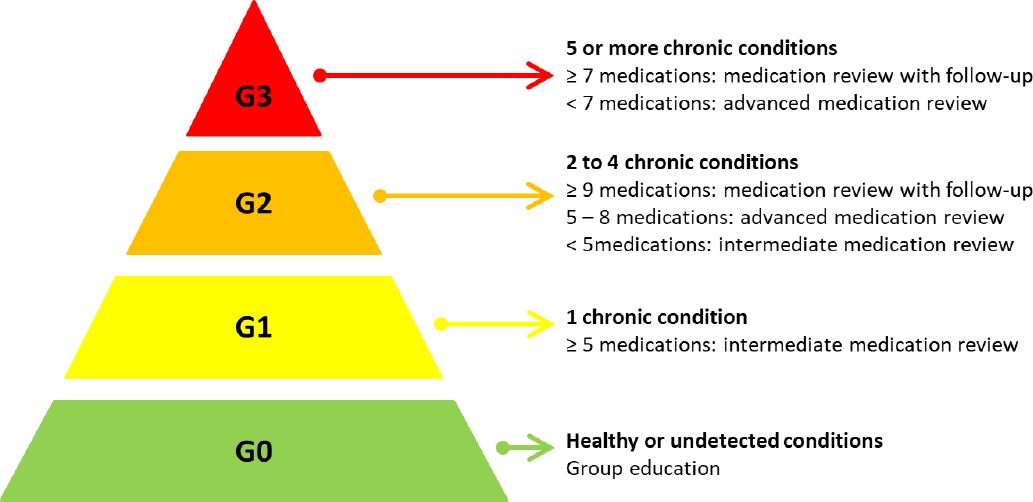

Most recent primary health care policies in Chile recognize the role of primary care pharmacists, employing pharmacists and in most instances including them in in care teams. Therefore, it is necessary that all large primary care centers have a full-time pharmacist (or more than one if the center is large enough). With the implementation of the multimorbidity care model, pharmacist would be able to provide specific services depending on patients’ needs. Within this model we propose a risk-based approach using the official classification and the number of medications, where higher-risk patients receive more complex and time-consuming pharmaceutical services. The proposed structure is described on Figure 1.31 Pharmaceutical services such as medication reconciliation, pharmacovigilance, individual education, home visits, and non-clinical services are not included in the proposal as we believe that they do not depend on this classification and should be provided when necessary.

Figure 1. Proposed structure for pharmaceutical services on the multimorbidity tare model. G0: null or unknown risk; G1: low risk; G2: intermediate risk; G3: high risk.

Medication review with follow-up has been shown to improve the control of some chronic conditions, as demonstrated in the Polaris trial, but its implementation may be constrained as it requires physicians’ time. Allowing pharmacists to initiate or modify existing pharmacological treatments for chronic conditions could improve the efficiency of the health system. This has been successfully tested in similar settings such as the UK’s General Practice Pharmacists program.34 Primary care pharmacists could receive additional 3 to 6 months certified training by academic institutions on prescribing of medicines and other clinical skills. Furthermore, the role of specialist pharmacists, currently restricted to hospitals, could be expanded to primary care, where they could enhance quality of care and provide more complex services.

The implementation of pharmaceutical services in private primary care will not be possible until coverage and remuneration is provided by ISAPREs. It is imperative that FONASA specifies reference pricing for pharmaceutical services to encourage the private sector. They could use the costs of services provided by other health professionals such as general practitioners or physiotherapists, the list of services and patient-per-hour rates specified for the public system.

CONCLUSION

As the provision of pharmaceutical services in community pharmacies in Chile is almost non-existent, there are many potential opportunities. Municipal pharmacies, being non-profit establishments, have a great opportunity to provide services, but there is a need for an extensive implementation program. Municipal pharmacies have several differences with primary care pharmacies as most of them lack private attention zones and access to the patient’s medical records, and there is no structured communication method with primary care physicians or pharmacists.

For other community pharmacies, if pharmaceutical services are not covered by insurance, it is unlikely that they will be implemented. The literature has described some models of funding, where patients or the government pay for these services based on their impact on health outcomes.35 However, apart from small pharmacies, we believe that these programs would not be successful until patients’ perception of pharmacies is improved, and pharmacists can provide pharmaceutical services as part of their main tasks. Furthermore, these services should not duplicate those provided at primary care centers to avoid repeating tasks and professional conflicts. Community pharmacies could integrate new services such as tobacco cessation programs, pharmaceutical immunization, and minor ailments prescription, all described by the literature as effective.36 37-38