INTRODUCTION

Colombia is a decentralized republic constituted by 32 departments (territorial units) and 1,204 municipalities which develop and implement the national government's policies for public health, and the provision and management of health services. It is a middle-income country with 50 million inhabitants.1

Colombia's health system

Since 1993, Law 100: General System of Social Security in Health (SGSSS by its Spanish acronym) established the current health system in Colombia. This Law guarantees equity in health services and mandates the compulsory enrolment of the population. Health equity focuses on providing equal access and quality health services to all the Colombia inhabitants, regardless of their ability to pay.2 SGSSS is composed of two subsystems: the "contributory", paid by workers, retired workers, self-employed workers with incomes equal to or greater than the legal minimum wage (300 USD per month in 2020) and their beneficiaries, and the "subsidized", where lower socio-economic groups are financed by the State. Both subsystems provide universal coverage, equal access to medicines, surgical procedures, medical and dental services through a basic and mandatory benefit package (identified as POS, by its Spanish acronym).2,3

In 2019, Colombia was reported to have highest universal health coverage in Latin America, with coverage for 95% of the population. However, 70% of people stated that they were dissatisfied with the quality of service indicating limitations to timely, equitable, and effective access to health care services despite this extensive health coverage.4 It is estimated that only 31% of people had access on the same day or the day after they sought ambulatory or first-level health care services. This is lower than the average of 51% for Latin America and the Caribbean region.4

Enrollment in the SGSSS is administered through public or private health insurance entities (EPS by its Spanish acronym), which collect and distribute the premium payments to the SGSSS Resource Managers. The Resource Manager provides reimbursement on a monthly basis to each of the EPS. The reimbursement, known as of Capitation Payment Units (UPC by its Spanish acronym), is a predetermined capitation fee for each unit of service and patient characteristics per enrolled persons (workers and their beneficiaries covered by the scheme). The UPC is fixed annually by the Ministry of Health, and it depends mainly on the characteristics of the population (age, sex, and place of residence) and probability of use of services. Each EPS has the responsibility to finance and deliver health care to their respective population in any location in Colombia. EPS contracts are agreed with one or more public or private institutions providing health services (IPS, by its Spanish acronym). Each EPS contracts a structured network at three level of care that provides and guarantees access to health services and medications included in a determined the health plan [Plan Obligatorio Salud] (POS by Spanish acronym). For medications and medical devices, networks of pharmacies are contracted by the EPS and patients must use those pharmacies to have their prescriptions dispensed.3 The private sector is used to complement the public system by people who can afford and purchase private health insurance and who may be able to pay for any out-of-pocket health expenditures. Approximately 5-10% of population have private health insurance.2,3,5

In 2018, 75% of health expenditure was attributed to public sources and the remaining 25% to private.6 In 2019, the out-of-pocket patient payments in Colombia were 20.6% of the health spending, compared to 42.7% in the Latin America region.7 Overall, per capita health care spending is considered to be low, USD 960 per person in 2017 (7.2% of 311,80 billion USD of Colombia's gross domestic product-GDP).8 Interestingly, the health care budget increased by 8.12% in 2020.9

Primary health care in Colombia

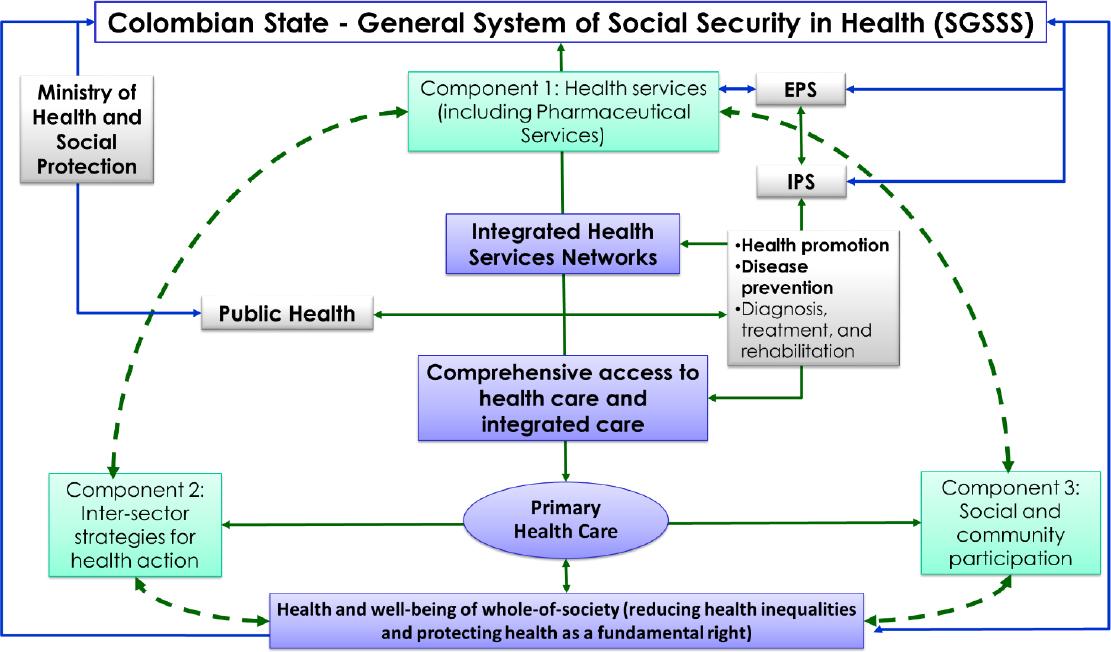

In 2007, Law 1122 established a the model for Primary Health Care (PHC) as the "Health Care Model".10 In 2011, Law 1438 improved and reinforced PHC as the strategy for achieving equity, comprehensiveness of access, and integrated care.11 In Colombia PHC is seen as a practical approach that guarantees the health and well-being of whole-of-society, contributing to reducing health inequalities and protecting health as a fundamental right. It is integrated through three interdependent components: health services, inter-sector strategies for health, and social and community participation. From the pharmacy's perspective, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection's guidelines on PHC include pharmaceutical services (PS). However, they do not specify the functions or responsibilities of pharmacists or community pharmacy. Pharmacists are included only in specialized healthcare or support services networks in the PHC model.

Comprehensive access to health care and integrated care are delivered by the provision of the public health programs (mainly by Ministry of Health and Social Protection) and health promotion, disease prevention, and diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation (mainly by EPS and IPS) through integrated health services networks (Figure 1).11

Figure 1. Primary Health Care as the strategy for achieving health equity, well-being of whole-of-society, and comprehensiveness in access to health care, and integrated careSGSSS: General System of Social Security in Health, identified as SGSSS by its Spanish acronym; EPS: health insurance entities, identified as EPS, by their Spanish acronym; IPS: Institutions Providing Health Services, identified as IPS, by their Spanish acronym.

The Ten-year Public Health Plan: 2012-2021

The Ten-year Health Plan Public (PHP), to coordinate with the Colombian socio-economic development, was developed through a process of participation of all country sectors, including Colombians of all ages, family organizations, health care experts, and the government.12 As in the PHC model, the ten-year PHP does not specify functions, services or responsibilities for pharmacists or community pharmacies. However, the ten-year PHP does include strategies, goals and indicators regarding rational use, adequate supply, quality, monitoring, and access to medicines and medical devices. The ten-year PHP does emphasize the role of pharmacovigilance, including the generation and dissemination of alert systems, active surveillance systems, off-label use, medication errors, risk management plans, and research in this field.12

The national pharmaceutical policy

In Colombia, the first National Pharmaceutical Policy (NPP) 1995-1998 was part of the health policies of the Andean Community.13 The Andean Community [Comunidad Andina] (CAN in Spanish) is a South American organization composed of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It was founded to encourage industrial, agricultural, social, and trade cooperation. The policy focused on ensuring equitable access to high quality essential drugs and promoting their rational use. Subsequently, in 2003, with the support of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), the NPP was developed which guaranteed accessibility, availability, and rational use of medicines and improved health equity.14 In 2012, the Council of Ministers (CONPES Social No. 155) approved the NPP, which incorporated: (a) price regulation, (b) parallel imports, (c) quality assurance, (d) guarantee of competition, (e) strengthening regulatory functions, including monitoring, and (f) regulation of the biotechnology products.11,15 Its overall goal was "to develop strategies that enable the Colombian population equitable access to effective medicines, through quality pharmaceutical services, under the principle of co-responsibility of the sectors and agents affecting their compliance".15

Pharmaceutical service (PS) is a broad term used in Colombia that include administrative, technical, supply, clinical and scientific activities related to medicines and medical devices, and their use in the promotion of health and the prevention, diagnosis, treatment of disease, and rehabilitation which contribute to the quality of life for individuals and community. The goals of the PS are: 1) promoting healthy lifestyles behaviors regarding medicines, 2) preventing risk factors arising from medication or medical devices errors, 3) promoting the rational use of medicines and medical devices, and 4) performing pharmacotherapy follow-up to patients in collaboration with other health care professionals.16 Thus, overall the concept of pharmaceutical services may be seen to transcend that of the community pharmacy and pharmaceutical care (PC).17 In addition to national decrees, local resolutions provide functions or activities related PS. For example: (a) procedure for registering and assessing the minimum conditions for standards of good practices for certifying PS and other health service providers thus ensuring that the services delivered to each patient are of suitable quality; and (b) guide for auditing and certifying good practices for pharmaceutical preparations.18-21

Intermediary private companies - pharmaceutical services

In Colombia it is mandatory to have registers of health care service providers in a public registry system.22 Among the 4,351 PS providers there are 3,699 (85%) certified to provide services for ambulatory care (out-patients) and 652 (15%) for hospital care (inpatient). Within the 3,699 PS certified for ambulatory care, there are 683 (18.5%) that are certified for both ambulatory and hospital care and 3,016 only for ambulatory care (72% private and 28% public).23

Pharmaceutical services in ambulatory settings are mainly provided by Intermediary Private Companies (logistics operators, Pharmaceutical Benefit Managers, or specialized drug distributors), which are contracted and paid directly by the EPS to provide medications directly to patients and to develop activities and processes aimed at achieving effective management and the rational use both of medicines and medical devices. It is estimated that there are approximately 20-25 recognized intermediary Private Companies distributed throughout the country, among which Audifarma, Cruz Verde, Evedisa, Éticos, Neuromédica, Dempos, Health Pharma, Medicarte, Cafam, Colsubsidio, and Comfandi are the most well-known.23 It is estimated that in 2018 some 31 million users were served.

In some cases, as an additional benefit or as a part of their agreement, these companies develop activities and processes focused on achieving the patient health outcomes (for instance, Pharmaceutical Care). These companies develop technical and administrative activities, such as the effective drug supply system, dispensing medications, and monitoring of clinical parameters, pharmacotherapeutic follow-up, and pharmacovigilance. They also participate in research in the pharmacy field. Some examples are studies on a care team approach to improve adherence, and identifying and reporting medication errors in a pharmacovigilance system.24,25

These intermediary private companies of PS management have emerged as new businesses in the health sector and they are similar to Pharmaceutical Benefits Management in the U.S. health system and are intermediaries between health insurers (EPS), pharmaceutical laboratories, and patients.23

Community pharmacy and drugstores

In Colombia, medications are also supplied by retail pharmacy establishments i.e. drugstores and pharmacies. Both pharmacy and drugstore are pharmaceutical establishments dedicated to sell allopathic, herbal and homeopathic products, cosmetics, personal hygiene products, medical devices and dietary supplements. Pharmacies may manufacture extemporaneous products while drugstore may not.17 In 2003, there were 14,208 drugstores and around 1,000 pharmacies; however by 2014, this number had increased to more than 20,000, mainly due to an increasing of number of drugstores.26,27 In these private establishments, many prescription medicines are sold without a medical prescription, for example 80% of antibiotics sold in drugstores and pharmacies were dispensed without a prescription; and 82% medicines with active pharmaceutical ingredients that are controlled (under national control laws) were sold without a prescription.28,29 Overall, these retail establishments do not meet minimum international standard for ambulatory care pharmacy practice and thus contribute minimally both to the rational use of medicines and health care and outcomes of patients.30,31

Other institutions in the pharmacy services offering

Since the 1980s, some hospitals (mainly public) have formed cooperatives to purchase medicines and medical devices directly from pharmaceutical companies. Their objectives have been to provide high quality inexpensive medications to patients. These cooperatives do provide some services oriented to the rational use of medicines, mainly education and training on technical and administrative activities oriented to an effective drug supply system and, pharmacotherapy follow-up and pharmacovigilance. For example, the Antioquia Cooperative (COHAN in Spanish) developed a study to assess the economic impact of the subsidized system dispensing of an analogue insulin dosage in diabetic patients and showed that pharmaceutical care program saving USD 2.82 per patient per month.32

There are also some not for profit institutions, funded through employees' contributions of 4%, which provide health services and have formed pharmacy networks in the locations to provide medications to workers and their families.24

There are a limited number of studies related to the characterization of ambulatories pharmaceutical services. A survey in Uraba (region of the department of Antioquia), found that in the 147 establishments that supplied medications: 35 (24%) were retail business of superstores or chain stores, 92 (63%) were pharmacies/drugstores, and 20 (14%) were linked to hospitals. Additional to medicines, 75 (51%) sold medical devices and 42 (29%) foods.33 A study conducted in Medellin and its Metropolitan Area reported that 340 (48.5%) of the 700 drugstores and pharmacies had a titular pharmacist (director) with a university degree in pharmacy or pharmacy technician.29 On a national basis it has been be estimated that in only 50% pharmacies and drugstores there is a titular pharmacist.29 In public and private hospitals pharmacies the presence of a person with pharmaceutical chemist degree (low, medium, and high level of complexity) or pharmacy technician (low level) is mandatory.16,17

In summary in Colombia there are an extensive number of ways that ambulatory patients access medications; 1) Intermediary private companies b) Public and private hospitals pharmacies (PS), and c) Retail establishments (drugstores and pharmacies). Intermediary companies and public and private hospital pharmacies (PS) dispensing medications to patients are charged to the health system (EPS), by contrast in retail establishments (pharmacies and drugstores) persons have to meet the cost of the medications albeit with some exceptions.

Pharmacy education and workforce

In Colombia, pharmaceutical chemist (equivalent to the pharmacist, licensed pharmacist, or pharmaceutical biochemist) is the five years university professional degree. Generally, in the four long established public universities education and curricula was been predominantly orientated, for a long time (1940-1990), to industrial production of drugs (production, quality control, and regulatory topics).24,25 Since 2008 other universities have begun to offer the pharmaceutical chemist degree and currently there are an additional 7 new universities that offer this degree.

The need for preparing staff to work in retail establishments, led by the University of Antioquia in 1967, to offer a 3 years pharmacy technician degree (pharmacy technician).24,25 Currently there are approximately 15 higher-educational institutions that offer the pharmacy technician degree.

Stimulated by the evolving role of the pharmacist legislative changes have ensued. Law 212 of 1995 and Decree 1945 of 1996 established and recognized Pharmaceutical Chemists as health care professionals. These laws and decree were influenced by the National College of Pharmaceutical Chemists.24,25,34,36 It is estimated that of the current 8,000 pharmaceutical chemists, about 25-30% work in patient care services, manly in hospital and ambulatory care. Some 25 years ago only 5 to 6% worked in patient care with the growth occurring predominantly in recent years.25 Pharmacists are being employed in private and public health management companies and in EPS managing audit and rational use of medicines programs.

Regulations allow that persons in charge of a pharmacy or drugstore could be a pharmacist, pharmacy technician, technical/auxiliary, or an "empirical with a certificate", i.e. persons without pharmacy education, but certified and approved as director ("vendor of drugs").16,17,36,37 This certificate is issued by Departmental Health Secretaries to persons who certify minimum work experience of 10 years in these establishment.16,24 Also, it is possible to find persons without pharmacy education or the certificate acting as directors of drugstores. Due to the combination of worker profiles in retail pharmacy establishments, the term "pharmacy staff" (person working in drugstores and pharmacies, and whose educational level may be a professional, technician, technical/auxiliary or with and without a certificate) is broad.38

In Colombia, over 50% of retail pharmacy establishments (drugstores and pharmacies) may have owners or employees without university education and training necessary to work as a pharmacist.24,25,29 One of the current NPP's strategic lines establishes the need to train and educate persons in drugstores and pharmacies to contribute to the rational use of medicines.15

OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE INTEGRATION OF COMMUNITY PHARMACY

Perspectives from public pharmacy policies and pharmaceutical services management companies

In Colombia since the 90's decade, there are more favorable conditions for pharmacist's participation and contribution to health system and patient's health outcome.39 These environmental facilitators include: (a) laws and regulations regarding pharmaceutical services (2005-2007), (b) establishment of a NPP (2012), and (c) opportunities associated with the consolidation of private health management companies providing health services with an interest in pharmaceutical services (since 1995).15-17,23,39 Intermediary Pharmaceutical Services management companies have been the organizations through which services have been implemented, and the results of interventions evaluated. Also, some studies have demonstrated positive effects of pharmacist intervention and programs and these results have been used to improve governmental regulations.16,17,40-44

In recent years there has been positive developments in the organisations and management of supply of medications and medical devices ensuring that the population is served in a timely manner, increasing accessibility and quality of medications.39 There have also been some pharmacovigilance programs, drug utilization studies, and information systems implemented.23 There is some progress in the implementation of PC services, such as dispensing, adherence, pharmacotherapy follow-up and pharmacovigilance, both in EPS and IPS.45-49 Nevertheless, there are challenges including the training and educating of persons working in drugstores and pharmacies with objective in improving the rational use of medicines in these establishments.38

Perspectives from universities and professional - academic associations

Since 2011, the Colombian Pharmaceutical Care Congress has been organized biennially, establishing itself as a forum for academics, health professionals, managers from EPS and IPS, and other health sector workers.45-49 Topics around PC, PS, and professional pharmacy services are shared and debated. The congress is a national joint effort of the academy and the pharmacy organizations. The themes for the 2019 congress were: tele pharmacy and the digital revolution to optimize the provision of professional pharmacy services; innovation as a critical process for consolidation of the research and new developments in PC; the science of implementation; and the comprehensive care routes for PS.49

Future trends: Telepharmacy, comprehensive care routes from the pharmaceutical services and postgraduate training in pharmacy practice

Due to the low availability of resources and pharmacists in some rural locations in Colombia, access to PS is limited, so telepharmacy may be a strategy to provide these health services. Government Resolution 2654 of 2019 established the provision of telehealth and telemedicine in the country, including telepharmacy.50 There has been some progress in the structuring of comprehensive care routes, ensuring the comprehensive and quality of care for individuals, families, and communities by the territorial entities, EPS, and IPS.51

Finally, it is necessary to further strengthen postgraduate training in pharmacy practice and pharmaceutical care, which in addition to consolidation skills and competencies for teaching and research in these fields, provide the opportunity to conduct research influencing the value of the pharmacist as the health care professional responsible for the effectivity and safety of pharmacotherapy to achieve the best possible health outcomes in the health system.52