INTRODUCTION

Minor ailments are often self-limiting conditions, with symptoms easily recognised and described by the patient and within the scope of a pharmacist's knowledge and training to manage.1 They can usually be managed with the appropriate use of non-prescription medicines and self-care.2-4 Developed countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom (UK) have developed models of care for the management of minor ailments (MMAs) by community pharmacists.5-9

Pharmacists have a responsibility to ascertain the services they offer for the MMAs leads to the appropriate use of medication and management of the ailment. Pharmacy technicians may also provide MMAs, and the pharmacy is often the first point of contact for consumers presenting with minor ailments.10

Community pharmacies in Indonesia range from small stand-alone to corporate pharmacies. In 2018, Indonesia had 24,874 community pharmacies, mainly located on Java Island.11 They open daily for extended hours and are owned by pharmacists and non-pharmacists. Legislation requires, non-pharmacist owners to employ a pharmacist.12,13 Community pharmacist and pharmacy technician consultations and advice on MMAs are common practice. The Indonesian Ministry of Health lists 10 minor ailments as manageable by community pharmacies and provides technical guidelines.14,15 Only 17% of community pharmacists in Jakarta, Indonesia, reported providing counselling and advice on MMAs, while 65% were provided by pharmacist assistants, 13% by non-pharmacist staff, and 5% by the pharmacy owner.16 Indonesian pharmacists also provide where appropriate referrals to another health care professional. Central Java (population 39 million) is one of 34 provinces located on Java Island in Indonesia.17 This study informs the development of pathways for implementing MMAs as an integral part of community pharmacy in Indonesia.

This research aimed to evaluate pharmacists' and pharmacy technicians' understanding of their scopes of practice, perceived competency and factors influencing the delivery of minor ailments services in Indonesian community pharmacies.

METHODS

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Curtin University, Human Research Ethics Committee, Australia (Approval number: HRE2019-0803); Indonesian Pharmacists Association (IAI) Central Java Regional Board, Indonesia (Approval number: B1-064/PD-IAI/Jawa-Tengah/IX/2019); Indonesian Pharmacy Technicians Association (PAFI) Central Java Regional Board, Indonesia (Approval number: 268/PAFI-JTG/XI/2019). Permission was obtained from the IAI and PAFI to approach attendees at their seminars to participate in the study.

The IAI and PAFI seminars

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians were surveyed at IAI and PAFI seminars which they attend to gain credits (SKP) towards their competency certificates which are mandatory to practise in a community pharmacy, requiring renewal every five years.

Inclusion criteria: pharmacists and pharmacy technicians attending IAI and PAFI seminars from Central Java currently working in a community pharmacy. Exclusion criteria: pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who practised in a dispensing-only pharmacy or practised within a doctor's clinic where the patients consulted the doctor prior to entering the pharmacy; working in the same pharmacy; and from pharmacies not located in Central Java.

Setting and sample size

The study populations were community pharmacists attending IAI and community pharmacy technicians attending PAFI individual seminars. A sample size of approximately 120 community pharmacists and 120 pharmacy technicians provided adequate precision and enabled statistical analyses to be performed (with alpha=0.05, this sample size has 80% power to identify differences in responses between pharmacists and technicians; prevalence estimates accurate to within ± 7%).

Questionnaire development

The community pharmacist's and pharmacy technician's questionnaires were developed based on current practice data and related literature in the community pharmacy setting in Indonesia, the Indonesian Ministry of Health technical guidelines on pharmacy services, Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA) Professional Practice Standards for MMAs, the UK pharmacy scheme for minor ailments studies and guidelines, Canadian minor ailments scheme guidelines, and previous Indonesian studies addressing community pharmacy triage services.1,5,7,18-26

The questionnaires were developed taking into consideration the Indonesian Pharmacy Service (IPS) standards, which describe minimum standards for pharmacy services in Indonesian community pharmacies.22,27 The types of minor ailments were developed based on the same sources.1,5,7,22,28 The questionnaire consisted of four parts: (1) The list of minor ailments developed for this study requiring perceived scope of practice responses by pharmacists and pharmacy technicians (one question), (2) Community pharmacist/pharmacy technician characteristics (10 questions), (3) Pharmacy demographics (eight questions), and (4) MMAs standard procedures (four questions). Pharmacy demographics included the type of pharmacy (independent/supermarket/co-located with a medical centre), pharmacy ownership, number of pharmacists, presence of consultation area, number of consumers seeking advice on MMAs; and pharmacist and pharmacy technician characteristics including gender, age, years of practice and MMAs training. If there were duplicate responses from the same pharmacy (identified from the questionnaire), the respondent with responsibility to manage or was senior in the pharmacy was chosen.

Questionnaire validation

The community pharmacist's and pharmacy technician's questionnaires were reviewed by three members of the pharmacy research team, five academic pharmacists with community pharmacy experience from Curtin University, eight Indonesian community pharmacists (pharmacist's questionnaire), and eight community pharmacy technicians (pharmacy technician's questionnaire) who were practising in pharmacies with varying business and practice models in Central Java, Indonesia for face and content validity. Their feedback was reviewed by the research team and the questionnaires were amended accordingly.

The questionnaires were prepared in English, then translated to Bahasa Indonesia by the investigator whose first language is Indonesian (forward translation); then back-translated to English by a sworn translator (back translation), which was then compared to the original version by three of the researchers whose first language was English. The Indonesian versions were pre-tested by community pharmacists or pharmacy technicians for appropriateness, and issues regarding clarity of the questions and the time to complete the survey.29 The pre-testing resulted in minor changes in the questionnaires. Both questionnaires were administered twice with a 10 day interval to the same community pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to assess test-retest reliability. Kappa scores measured the agreement between raters, where the MMAs services were grouped for Likert scale ratings of 1-3 and 4-5 for test-retest reliability. The Kappa scores ranged between 0.41 to 1.00, which was acceptable for health research studies.30

Questionnaire distribution

The questionnaires were distributed to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians at separate seminars. IAI seminars: Pekalongan region, Surakarta city, Semarang city, on 5, 12, and 19 January 2020. PAFI seminars: Brebes city, Semarang city, Surakarta city, on 29 December 2019, 26 January and 2 February 2020. The investigator attended the seminar and distributed the questionnaires at the registration desk prior to the seminar. Attending pharmacists or pharmacy technicians were encouraged to participate. Completed questionnaires were submitted at the registration desk (anonymous). Participants could provide their name and contact details on a separate form when submitting their completed questionnaire for a draw to win a cash prize. These contact details were collected only for the draw, and were separate to the survey responses and kept confidential, as approved by the Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

Ordinal variables such as age group, and years of practice were dichotomised based on the distribution of responses, and analysed using non-parametric tests. Descriptive statistics summarised demographics and characteristics. Respondents age were categorised based on the median values.

Percentage of Common Responses (PCR) described similarity of perceived scopes of practice for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. PCR was determined as the mean sum of percentages of combined pharmacists' and pharmacy technicians' responses data.31 Binary logistic regression compared perceptions of scope of practice competence of MMAs between pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. For the purpose of this analysis, the scope of minor ailment management was coded into: within scope of pharmacy technician and only within scope of pharmacist. Responses where the ailment was considered beyond the scope of a pharmacist (or a pharmacy technician) were described graphically, but excluded from the logistic regression analysis. Multivariate logistic regression evaluated characteristics independently associated with the scope of practice competence of MMAs. Demographic, pharmacy, and practice variables were initially included in the logistic regression, and the least significant variables were dropped sequentially until only factors with a p-value <0.05 remained in the model. The Kruskal Wallis-test analysed differences between demographic/characteristics and MMAs standard procedures responses between the three seminars datasets for IAI and PAFI. The data from the three seminars were to be collapsed and aggregated if no statistically significant differences in factors occurred (p>0.05). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The comparative results or percentage (%) values were presented as P=data from community pharmacist survey; T=data from pharmacy technician survey.

RESULTS

The demographic characteristics (age, gender, and level of education) of the respondent pharmacists and pharmacy technicians were not significantly different between the first, second, and third seminars (p-values >0.05). These data were aggregated for subsequent analyses.

In total, 234 pharmacists attended three separate IAI seminars (59 pharmacists the first, 37 the second, and 138 the third seminar). Seven declined to participate, leaving 227 questionnaires distributed. Nine pharmacists had registered to attend but were absent. Of those distributed, 196 were returned. Eleven were excluded: two pharmacies located within a doctor's clinic, two located in a medical skincare clinic, one pharmacist from a different province, two duplicates, and four incompletes. The response rate was 81.5% (185/227) of useable questionnaires.

In total, 216 pharmacy technicians attended the three PAFI seminars (54 technicians the first, 99 the second, and 63 the third seminar). Five declined to participate, leaving 211 questionnaires distributed, of which 151 were returned. Nine questionnaires were excluded: two pharmacies were within a doctor's clinic and seven were incomplete. The response rate was 67.3% (142/211) of useable questionnaires.

Table 1 provides the demographic profiles of 185 pharmacist and 142 pharmacy technician respondents. Most pharmacist and pharmacy technician respondents were female (P=161/185, 87.0%; T=122/142, 85.9%), under the age of 40 years for pharmacists (165/185, 89.2%), and under the age of 30 years for pharmacy technicians (125/142, 88.1%). Most pharmacist respondents held an Apothecary/Pharmacist professional degree (168/185, 91%) and more than half of the pharmacy technician respondents held a diploma degree (89/142, 63%). Almost half of the pharmacist respondents worked on average more than 30 hours per week (90/185, 48.6%).

Table 1. Demographic profiles of the pharmacist and pharmacy technician respondents

| Pharmacists (n=185) | Pharmacy Technicians (n=142) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) | Characteristics | n (%) |

| Gender | Gender | ||

| Male | 24 (13.0) | Male | 20 (14.1) |

| Female | 161 (87.0) | Female | 122 (85.9) |

| Age (years) | Age (years) | ||

| 21-30 | 89 (48.1) | 16-20 | 12 (8.5) |

| 31-40 | 76 (41.1) | 21-30 | 113 (79.6) |

| 41-50 | 13 (7.0) | 31-40 | 15 (10.6) |

| >50 | 7 (3.8) | 41-50 | 2 (1.4) |

| Years of registered | Years of registered | ||

| <2 years | 37 (20.0) | <2 years | 24 (16.9) |

| 2-5 years | 46 (24.9) | 2-5 years | 76 (53.5) |

| 6-10 years | 52 (28.1) | 6-10 years | 32 (22.5) |

| 11-15 years | 35 (18.9) | 11-15 years | 9 (6.3) |

| >15 years | 15 (8.1) | >15 years | 1 (0.7) |

| Years of practice | Years of practice | ||

| <2 years | 44 (23.8) | <2 years | 23 (16.2) |

| 2-5 years | 47 (25.4) | 2-5 years | 79 (55.6) |

| 6-10 years | 47 (25.4) | 6-10 years | 28 (19.7) |

| 11-15 years | 38 (20.5) | 11-15 years | 11 (7.7) |

| >15 years | 9 (4.9) | >15 years | 1 (0.7) |

| Level of education | Level of education | ||

| Apothecary Degree | 168 (90.8) | Pharmacy assistant school | 36 (25.4) |

| Master's Degree | 17 (9.2) | Diploma | 89 (62.7) |

| Position in the pharmacy | Bachelor of pharmacy | 13 (9.2) | |

| Pharmacy Manager and Owner | 53 (28.6) | Apothecary degree | 4 (2.8) |

| Pharmacy Manager | 102 (55.1) | ||

| Employee Pharmacist | 30 (16.2) | ||

| MMAs training in the last 3 months | MMAs training in the last 3 months | ||

| Yes | 113 (61.1) | Yes | 69 (48.6) |

| No | 72 (38.9) | No | 73 (51.4) |

| Total time on MMAs training (n=113) | Total time on MMAs training (n=69) | ||

| 1-5 hours | 56 (49.6) | 1-5 hours | 52 (75.4) |

| 6-10 hours | 43 (38.1) | 6-10 hours | 17 (24.6) |

| 11-15 hours | 2 (1.8) | >10 hours | 0 (0.0) |

| >15 hours | 12 (10.6) | ||

Independently owned pharmacies (P=110/185, 59.5%; T=91/142, 64.1%) were the highest proportions of community pharmacies where pharmacist and pharmacy technician respondents worked (Table 2). Almost two-fifths of the pharmacist (72/185, 38.9%) and pharmacy technician (51/142, 35.9%) respondents worked in pharmacies with a pharmacist owner, while the remainder had non-pharmacist owners. More than half of the pharmacies operated for seven days per week with an average working day of 15 hours (median 13.5 hours). Only one pharmacy (1/142, 0.7%) did not have a pharmacy manager as reported in the pharmacy technician survey.

Table 2. Pharmacy characteristics reported by the pharmacists and pharmacy technician respondents

| Pharmacists (n=185) | Pharmacy Technicians (n=142) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) | Characteristics | n (%) |

| Type of pharmacy | Type of pharmacy | ||

| Independent | 110 (59.5) | Independent | 91 (64.1) |

| Franchise | 25 (13.5) | Franchise | 19 (13.4) |

| Supermarket | 3 (1.6) | Supermarket | 0 (0.0) |

| Co-located with a medical centre | 40 (21.6) | Co-located with a medical centre | 27 (19.0) |

| Other | 7 (3.8) | Other | 5 (3.5) |

| Pharmacy ownership | Pharmacy ownership | ||

| Pharmacist | 72 (38.9) | Pharmacist | 51 (35.9) |

| Non-pharmacist | 68 (36.8) | Non-pharmacist | 67 (47.2) |

| Non-pharmacy company | 8 (4.3) | Non-pharmacy company | 0 (0.0) |

| Regional owned | 5 (2.7) | Regional owned | 2 (1.4) |

| State-owned | 17 (9.2) | State-owned | 21 (14.8) |

| Other | 14 (7.6) | Other | 1 (0.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Private room for consultation | Private room for consultation | ||

| Yes | 149 (80.5) | Yes | 108 (76.1) |

| No | 35 (18.9) | No | 34 (23.9) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Average consumers per week | Average consumers per week | ||

| <100 | 23 (12.4) | <100 | 5 (3.5) |

| 100-150 | 28 (15.1) | 100-150 | 29 (20.4) |

| 151-250 | 32 (17.3) | 151-250 | 18 (12.7) |

| 251-350 | 24 (13.0) | 251-350 | 16 (11.3) |

| 351-450 | 14 (7.6) | 351-450 | 15 (10.6) |

| 451-550 | 15 (8.1) | 451-550 | 21 (14.8) |

| 551-700 | 20 (10.8) | 551-700 | 16 (11.3) |

| >700 | 28 (15.1) | >700 | 22 (15.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Average MMAs patients per week | Average MMAs patients per week | ||

| <10 | 7 (3.8) | <10 | 3 (2.1) |

| 10-20 | 20 (10.8) | 10-20 | 10 (7.0) |

| 21-30 | 27 (14.6) | 21-30 | 9 (6.3) |

| 31-40 | 10 (5.4) | 31-40 | 12 (8.5) |

| 41-50 | 24 (13.0) | 41-50 | 17 (12.0) |

| 51-60 | 13 (7.0) | 51-60 | 18 (12.7) |

| 61-70 | 16 (8.6) | 61-70 | 19 (13.4) |

| >70 | 67 (36.2) | >70 | 54 (38.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Employed pharmacist | Employed pharmacist | ||

| 0 | 98 (53.0) | 0 | 41 (28.9) |

| 1 | 67 (36.2) | 1 | 86 (60.6) |

| 2 | 19 (10.3) | 2 | 15 (10.6) |

| >2 | 1 (0.5) | >2 | 0 (0.0) |

| Pharmacy technician | Pharmacy technician | ||

| 0 | 11 (5.9) | 0 | 0 (0.0) |

| 1-2 | 137 (74.1) | 1-2 | 59 (41.6) |

| 3-4 | 30 (16.2) | 3-4 | 66 (46.5) |

| 5-6 | 3 (1.6) | 5-6 | 13 (9.1) |

| >6 | 4 (2.2) | >6 | 4 (2.8) |

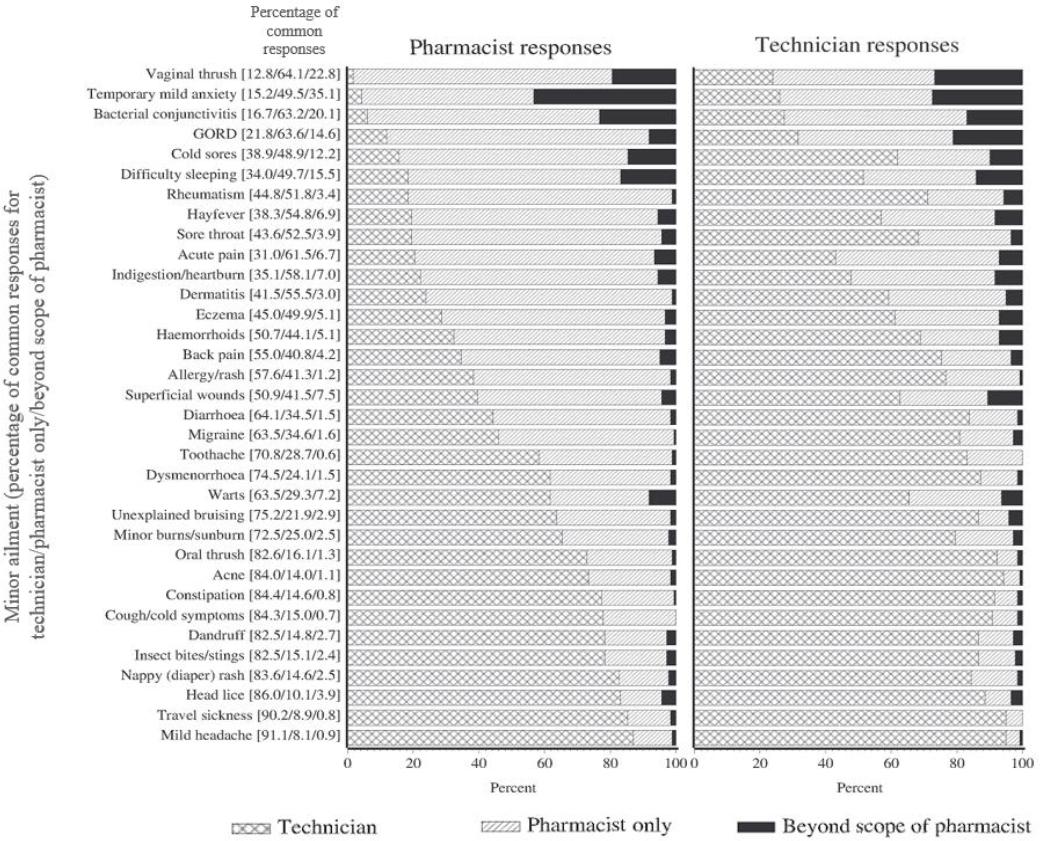

The responses of pharmacist and pharmacy technician respondents to 34 proffered minor ailments asking their perceptions of scopes of practice for pharmacy technicians (and therefore pharmacists), pharmacists or beyond the scope of pharmacists (and therefore both) is reported in Figure 1. PCR values for combined pharmacist and pharmacy technician responses to manage each of the ailments or if it reported beyond the scope of both are also provided. Notably pharmacists and pharmacy technicians responded similarly that the following ailments were generally managed by pharmacists: vaginal thrush, bacterial conjunctivitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), and acute pain. Overall, there is a discordance in the perceived scopes of practice where the responses of pharmacists indicated a lower scope than pharmacy technicians as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The responses of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to 34 proffered minor ailments asking their perceptions of scope of practice for pharmacy technicians (and therefore pharmacists), pharmacists or beyond the scope of pharmacists and therefore both

A majority of pharmacy technicians reported performing minor ailments consultations (Table 3). However, where they considered the minor ailment was not within their scope of practice, they referred the patient to the pharmacist (T=120/142, 84.5%).

Table 3. Pharmacists' (n=185) and pharmacy technicians' (n=142) responses regarding who normally performs the management of minor ailments functions in their pharmacy

| MMAs activities; n (%) | Pharmacist | Technician | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluating patient-specific information to assess medication therapy | <0.001 | ||

| By a pharmacist | 171 (92.4) | 93 (65.5) | |

| By a pharmacy technician | 14 (7.6) | 49 (34.5) | |

| Reviewing medication allergies | <0.001 | ||

| By a pharmacist | 175 (94.6) | 89 (62.7) | |

| By a pharmacy technician | 10 (5.4) | 53 (37.3) | |

| Providing minor ailments counselling | <0.001 | ||

| By a pharmacist | 132 (71.4) | 47 (33.1) | |

| By a pharmacy technician | 53 (28.6) | 95 (66.9) | |

| Recommending Western over-the-counter and pharmacy-only medicines | <0.001 | ||

| By a pharmacist | 138 (74.6) | 62 (43.7) | |

| By a pharmacy technician | 47 (25.4) | 80 (56.3) | |

| Screening or point-of-care testing recommendations | <0.001 | ||

| By a pharmacist | 141 (76.2) | 64 (45.1) | |

| By a technician | 44 (23.8) | 78 (54.9) | |

| Providing advice to refer the patient to the doctor | <0.001 | ||

| By a pharmacist | 175 (94.6) | 107 (75.4) | |

| By a pharmacy technician | 10 (5.4) | 35 (24.6) | |

| Providing written and/or verbal communication to the doctor | <0.001 | ||

| By a pharmacist | 178 (96.2) | 120 (84.5) | |

| By a pharmacy technician | 7 (3.8) | 22 (15.5) |

p-value <0.05 indicates that pharmacists and technicians differed in their responses

Table 4 shows eleven minor ailments with PCR values between 40-60%, reported by pharmacist and pharmacy technician respondents. However, the odds of each being within the perceived scope of practice of a pharmacist differed significantly between respondents (p<0.0001). Other factors more often independently associated with the ailment being within the scope of the pharmacist included practising for more than 6 years and the pharmacist assessing medication therapy. Where the pharmacy was co-located with a medical centre, the odds of the scope of practice being within that of a pharmacist were significantly lower.

Table 4. Univariate and Multivariate analysis of factors influencing perceived scope of practice of management of minor ailments with PCR values between 40%-60% as perceived by pharmacist (n=185) and pharmacy technician (n=142) respondents. The Odds Ratio (OR) shows the odds of responding that the ailment is within the scope of practice of the pharmacist only

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Allergy/Rash | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 5.33 (3.25-8.73) | 3.92 (2.27-6.76) | ||

| Pharmacy type | 0.0201 | |||

| Not co-located | 1 (reference) | |||

| Co-located | 0.47 (0.25-0.89) | |||

| Pharmacist assesses medication therapy | 0.0453 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.15 (1.02-4.54) | |||

| Pharmacist provides ailment counselling | 0.0386 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 1.76 (1.03-3.01) | |||

| Technician work hours | 0.0094 | |||

| Low | 1 (reference) | |||

| High | 2.02 (1.19-3.42) | |||

| Back pain | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 6.24 (3.76-10.38) | 4.85 (2.85-8.26) | ||

| Years of practice | 0.0402 | |||

| < 6 years | 1 (reference) | |||

| 6 or more years | 1.70 (1.02-2.83) | |||

| Pharmacist assesses medication therapy | 0.0327 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.19 (1.07-4.49) | |||

| Cold sores | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 9.79 (5.65-16.95) | 11.40 (5.96-21.80) | ||

| Years of practice | 0.0056 | |||

| < 6 years | 1 (reference) | |||

| 6 or more years | 0.37 (0.18-0.75) | |||

| Training in MMAs | 0.0476 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 0.55 (0.30-0.99) | |||

| Number of technicians as staff | 0.0353 | |||

| Low | 1 (reference) | |||

| High | 0.50 (0.26-0.95) | |||

| Consumers seeking advice on MMAs | 0.0238 | |||

| Low | 1 (reference) | |||

| High | 2.06 (1.10-3.84) | |||

| Dermatitis | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 5.20 (3.20-8.46) | 3.68 (2.13-6.33) | ||

| Years of practice | 0.0360 | |||

| < 6 years | 1 (reference) | |||

| 6 or more years | 2.09 (1.05-4.15) | |||

| Training in MMAs | 0.0315 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 0.55 (0.32-0.95) | |||

| Pharmacist reviewing medication allergies | 0.0283 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.40 (1.22-4.75) | |||

| Diarrhoea | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 6.91 (3.99-11.95) | 5.28 (2.92-9.57) | ||

| Training in MMAs | 1 (reference) | 0.0283 | ||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.84 (1.07-3.18) | |||

| Pharmacy type | 0.0318 | |||

| Not co-located | 1 (reference) | |||

| Co-located | 0.49 (0.25-0.94) | |||

| Consultation area | 0.0253 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.22 (1.10-0.46) | |||

| MMAs activities spent at pharmacy | 0.0344 | |||

| Low | 1 (reference) | |||

| High | 0.53 (0.29-0.95) | |||

| Pharmacist assesses medication therapy | 0.0023 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 4.00 (1.64-9.74) | |||

| Consumers seeking advice on MMAs | 0.0344 | |||

| Low | 1 (reference) | |||

| High | 0.53 (0.29-0.95) | |||

| Eczema | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 4.60 (2.84-7.44) | 3.63 (2.18-6.06) | ||

| Gender | 0.0238 | |||

| Female | 1 (reference) | |||

| Male | 0.43 (0.20-0.89) | |||

| Pharmacist assesses medication therapy | 0.0002 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 3.76 (1.86-7.61) | |||

| Hayfever | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 6.38 (3.83-10.63) | 4.19 (2.30-7.63) | ||

| Employment of employee pharmacist | 0.0247 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 1.96 (1.09-3.52) | |||

| Consultation fee | 0.0017 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.35 (1.13-4.92) | |||

| Pharmacist assesses medication therapy | 0.0006 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 3.43 (1.70-6.90) | |||

| Haemorrhoids | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 5.72 (3.47-9.41) | 4.35 (2.55-7.42) | ||

| Pharmacist reviewing medication allergies | 0.0172 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.48 (1.18-5.25) | |||

| Consumers who present to a pharmacy | 0.0339 | |||

| Low | 1 (reference) | |||

| High | 0.59 (0.36-0.96) | |||

| Rheumatism | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 13.41 (7.80-23.05) | 19.52 (10.41-36.61) | ||

| Gender | 0.0019 | |||

| Female | 1 (reference) | |||

| Male | 0.26 (0.11-0.61) | |||

| MMAs activities spent at pharmacy | 0.0126 | |||

| Low | 1 (reference) | |||

| High | 0.46 (0.25-0.85) | |||

| Pharmacy manager working hours | 0.0036 | |||

| Low | 1 (reference) | |||

| High | 2.47 (1.34-4.52) | |||

| Sore throat | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 9.50 (5.65-15.96) | 5.77 (3.30-10.11) | ||

| Years of practice | 0.0151 | |||

| < 6 years | 1 (reference) | |||

| 6 or more years | 2.01 (1.15-3.53) | |||

| Pharmacist assesses medication therapy | 0.0129 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.65 (1.23-5.71) | |||

| Pharmacist reviewing medication allergies | 0.0286 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.46 (1.10-5.49) | |||

| Superficial wounds | ||||

| Respondent: | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| Technician | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Pharmacist | 3.34 (2.06-5.41) | 2.74 (1.65-4.56) | ||

| Pharmacist assesses medication therapy | 0.0199 | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.27 (1.14-4.54) | |||

DISCUSSION

This study has evaluated the perceived competence of current community pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to manage selected MMAs in Central Java. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate Indonesian pharmacists' and pharmacy technicians' perceived scopes of practice and competency regarding their pharmacy-based services for the MMAs.

Typical response rates for paper-based surveys range from 30%-55%.32 This study had response rates of 81.5% for pharmacists and 69.8% the pharmacy technicians. This higher response rate minimised bias of non-participants affecting the results.32 Pharmacies located within a doctor's clinic where the patients were required to see the doctor prior to visiting the pharmacy were excluded from this study because the initial assessment and consultation for minor ailments were with the doctor and not the pharmacist.

A high proportion of younger female respondents was found in both pharmacist and pharmacy technician groups compared with data for all registered pharmacists and pharmacy technicians in Central Java (p<0.001). However, it is not possible to ascertain the representativeness of the samples because the register does not include employment category such as community, hospital, industry. The pharmacy characteristics reported in this study are comparable with gender, type of pharmacy, and pharmacy ownership reported in studies conducted in community pharmacies in Bandung and Jakarta, Indonesia.33-35

Scope and competence of minor ailment management

The Indonesian Ministry of Health's technical guidelines for pharmacy practice lists 10 minor ailments as manageable by community pharmacies. However, the majority of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians reported perceived competency in a wider range of MMAs. This list is dated and these findings indicate a need to review the Indonesian pharmacy practice technical guidelines for MMAs. Minor ailments are commonly classified as non-complicated and may be managed within a community pharmacy setting. Our findings have suggested that pharmacist's perceived competence to manage certain ailments was much broader than the 10 listed by the Ministry and embraced the 34 included in this study. Discordance is evident where pharmacy technician's perceptions of their scope was wider than that ascribed by community pharmacists. Vaginal thrush, bacterial conjunctivitis, GORD, and acute pain were minor ailments that were perceived as limited to a pharmacist. Minor ailments such as toothache, oral thrush, and constipation were clearly within the scope of a pharmacy technician. Temporary mild anxiety and difficulty sleeping had higher levels reported beyond the scope of a pharmacist to manage in the community pharmacy (PCR 35.1% and 15.5%), which also implies beyond the scope of a pharmacy technician.

Pharmacy technician respondents indicated that they felt competent to manage not only straightforward minor ailments but also those requiring detailed assessment and treatment requiring pharmacist-only medicines. Notably migraine was included in pharmacy technicians perceived competence to manage. This was a surprising finding but possibly indicated confusion with headaches. Competence to manage MMAs needs to be evaluated in a future study.

There appears to be a discordance and similarities between pharmacists' and pharmacy technicians' perceptions of their scopes of practice and those of each other. This highlights that the pharmacists' and pharmacy technicians' perspectives toward a minor ailment may differ or that one might not be fully cognizant of the scopes of practice of the other group. Inadequate understanding of each other's capabilities may pose a problem for some MMAs, raising safety concerns, and contributing to inconsistent practice.10,36

Factors that influenced perceived scope of practice of MMAs associated with pharmacy characteristics

This study found that where a pharmacist assessed patients' medication therapy, provided minor ailment counselling, and had six or more years of practice experience, were associated with these MMAs being within a pharmacist's scope of practice. Co-location with a medical practice was associated with ailments being less likely within a pharmacist's scope and presumably were referred more often for medical consultation due to the accessibility to a doctor. Pharmacists assess patients' medication therapy to gain patient information related to safety and appropriate use. Allergy/rash is a common skin condition in which patients sought advice from pharmacists. Thus, pharmacist's clinical decision making is essential to identify if the management of the rash was within their scope of practice or required referral.37

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should adhere to codes of practices that ensure they manage ailments within their areas of competence and health authorities must support them through the development of appropriate regulations. However, these regulations must not restrict pharmacies in the provision of guidance and support where they have the expertise. Future research should evaluate the expertise of community pharmacists and pharmacy technicians and their influence upon consumers when providing MMAs services. Pharmacy education and training might also contribute to differences in perceptions of professional competency between community pharmacists and pharmacy technicians regarding MMAs.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include its reliance on participants' perceptions and self-reports of scopes of MMA services in Indonesian community pharmacies. Recruiting samples attending IAI and PAFI seminars may not be representative of all community practitioners. No suitable sampling frames are available to enable this evaluation. However, all pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are required to attend a range of seminars used in this study, for re-registration. Therefore, some caution should be exercised in generalising these findings.

CONCLUSIONS

The scope of provision of MMA services by pharmacists and pharmacy technicians needs to be more broadly established. Importantly, given the discordant perceptions to MMAs by pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, a strong need exists to ensure that each professional practises within their scope of practice to achieve safe pharmacy practices. Professional experience, patient counselling and pharmacy location influence perceived scope of practice. Professional and government reviews of the scopes of MMA practice is essential to enhancing primary health care in Indonesia.