A large body of research has demonstrated the role of compassion in diverse mental health problems, especially in eating disorders (ED) (Ferrari et al., 2019; Turk & Waller, 2020). In the field of body image (BI), the role of self-compassion has been related to the promotion of positive affect and positive BI dimensions (Albertson et al., 2015; Ziemer et al., 2019), as well as decreases in negative BI features (Kelly & Waring, 2018; Piran, 2015), leading to a lower risk of ED (Turk & Waller, 2020). Nonetheless, during the last few years, there has been a surge in interest in the field of BI on the novel concept of compassion towards the body (Altman et al., 2020).

While the self-compassion construct includes the concepts of common humanity or kind acceptance from a more general trait-level stance (Neff, 2003; Mills, 2022), body compassion (BC) shifts the focus to the role of compassion directed specifically towards one's own body, merging the constructs of BI (Cash, 2000) and compassion (Neff, 2003). This construct is composed of 3 factors (Altman et al., 2020): (1) defusion (i.e., decentering from painful thoughts rather than over-identifying thoughts of one's body limitations or inadequacies); (2) common humanity (i.e., the ability to face one's negative BI-experiences as part of a human experience rather self-isolating); and (3) acceptance (i.e., acceptance of the body and body-related painful thoughts and feelings). Despite the scarce study of this construct, BC has already been favorably linked to positive BI (e.g., body flexibility) (Altman et al., 2017), and also to lesser BI disturbance (e.g., feeling of body shame or disordered eating patterns) (Barata-Santos et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2018). Additionally, similarly to self-compassion, BC also has been associated with higher positive affect, such as feeling determined or inspired (Altman et al., 2020).

Self-compassion-focused interventions have been shown to promote positive BI and decrease negative BI (Ferrari et al., 2019; Turk & Waller, 2020). Hence, directing compassion specifically toward the body could be a valuable element on the way to more effective ED prevention and treatment approaches (Oliveira et al., 2018), as they may explicitly focus on one's appearance (vs. the general “self”) when promoting a kind, accepting and non-judgmental attitude towards oneself (Altman et al., 2020). In recent years, the constructs of self-compassion and BC have been closely related to positive BI (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015), but more studies are needed to delineate the role BC plays in the risk factors of ED, as well as the underlying mediators of this relationship.

In this regard, body appreciation has emerged as a promising protective mechanism in relation to ED (Oliveira et al., 2017; Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015), which promotes a positive relationship regarding one's body. This construct has been conceptualized as the attitude of holding favorable opinions about one's body regardless of perceived physical imperfections while paying attention to how the body feels, engaging in healthy behaviors, and rejecting unreasonable beauty ideals (Avalos et al., 2005). Body appreciation has been widely linked to positive psychological constructs (Tylka, 2019), particularly those related to the adaptive emotional regulation processes (Marta-Simões & Ferreira, 2019; Ramos-Martins et al., 2021). Moreover, body appreciation has also been negatively associated with the risk of ED (Avalos et al., 2005; Linardon et al., 2020). Specifically, it has been associated with reduced body-based social comparison (Siegel et al., 2020), or reduced thin-ideal internalization (Halliwell et al., 2015). The practice of a mindful and non-judgmental attitude towards one's experiences could lead to a more balanced and appreciative (vs. the judgmental) relationship with one's own body (e.g., Andrew et al., 2016; Homan & Tylka, 2015). Additionally, taking into consideration Webb et al.'s affect regulation framework (2014) or the research conducted by Homan and Tylka (2015), self-compassion along with body appreciation is promoting more adaptive emotional strategies when facing BI-related threats. However, more studies regarding these constructs are needed in order to disentangle the protective role of compassion and positive BI-related constructs in dealing with the risk of ED.

In a similar line, BI-focused shame has recently arisen as one of the widely acknowledged predictors of ED (Nechita et al., 2021). Body shame -a painful self-conscious emotion- is developed from negative feelings towards one's own body and perceiving its characteristics as unattractive and/or inadequate (Duarte et al., 2015). The construct has been divided into two dimensions (Duarte et al., 2015): external body shame, which is experienced when a person perceives that their bodily features (e.g., overweight) could be rejected by others; and internal body shame, which occurs when the individual internalizes other's negative views of their body and perpetuates self-devaluating judgment of one's own body.

According to the Objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), BI-focused shame arises when the individual fails to meet the internalized thin-body ideals, leading to the activation of the maladaptive emotion regulation processes (e.g., body surveillance) (e.g., Duarte et al., 2016; Oliveira et al., 2017) in order to decrease distress (e.g., Gilbert & Miles, 2014). In the long term, these responses have been associated with feelings of insecurity, and overall, a greater risk of psychopathology (see Gilbert & Miles, 2014). In contrast, the self-compassion practice may adaptively decrease shame (Braun et al., 2016) through the activation of the self-soothing system (Gilbert, 2014). However, in order to advance the field of research on BI and identify new protective factors that could effectively prevent ED, it is necessary to conduct further studies and investigations. In the current study, we focus on examining the protective role of BC (not general self-compassion), and its potential mediators, on the risk factors of ED. Despite being a novel construct, BC could enable the inclusion of a body-specific compassionate perspective (e.g., the body acceptance subscale of the BCS) (Oliveira et al., 2018), which may be of particular interest in therapies that approach specific body-related risk factors (e.g., BI-related shame).

Firstly, as the questionnaire designed to measure BC has not been validated in Spanish, we tested the psychometric properties of the Body Compassion Scale (BCS; Altman et al., 2020) to confirm its three-factor structure in a sample of Spanish women. To our knowledge, no research on the psychometric qualities of BCS has been conducted in the Spanish-speaking population and there is a need to have validated measurements for this novel construct that could allow a deeper understanding of the role of BC in the prevention of EDs. Moreover, we expected the construct of BC to show good convergent validity with positive BI measures (e.g., body appreciation) and divergent validity with negative BI-related measures (e.g., risk of developing EDs).

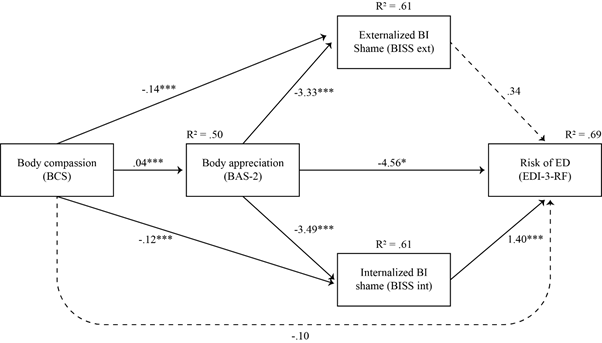

Secondly, we aimed to explore whether BC, mediated by body appreciation, plays a protective role in EDs' risk through body shame (see Figure 1). To this end, based on the findings of previous studies, we set up the following hypotheses: (H 1a) BC will be directly and negatively associated with body shame and (H 1b) the risk of ED, and (H 2) body appreciation and BI shame will mediate the relationship between BC and risk of ED.

Note. BCS= Body Compassion Scale; BAS-2 = Body Appreciation Scale-2; BISS = Body Image Shame Scale; EDI-3-RF = Eating Disorders Inventory-3 Referral Form; BI = Body Image; ED = Eating Disorders.

Figure 1. Proposed Serial-parallel Mediation Model

Method

Participants

The sample was comprised of 288 Spanish women from the general population (M Age = 24.65; SD Age = 5.02; M BMI = 21.93; SD BMI = 2.88). Participants were excluded from the study if they had a history of ED, were under 18 or over 40 years old, had a Body Mass Index (BMI) below 17 or above 34.9, or came to Spain when they were more than 7 years old. Participants' data were deleted if they failed at least one out of the four embedded “attentional control questions” (e.g., “Respond 5 if you are reading this”).

All the participants provided their informed consent before filling out the questionnaires, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia (Procedure number: 1127840).

Instruments

As a first step of the survey, all participants provided their sex, age (in years), marital status, education level, employment status, height, and weight. BMI was calculated by dividing current weight (in kg) by height squared (in m).

Risk of ED. The Eating Disorder Inventory-Referral Form (EDI-3-RF; Garner, 2004; Elosua et al., 2010). The EDI-3-RF is composed of 25 items with a 6-point Likert scale (1 = always; 6 = never). It was designed to measure EDs' risk and can be administered in non-clinical and clinical settings. The Spanish validation showed good internal consistency in the non-clinical sample. In our sample, Cronbach's alphas for the three dimensions were .91, .85, and .87, respectively.

Self-Compassion. The Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF, Raes et al., 2011; Garcia-Campayo et. Al., 2014). This scale is a 12-item designed to measure the tendency to treat oneself with kindness, recognize common humanity, and be mindful when considering negative aspects of oneself on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = almost never; 5 = almost always). As in the Spanish validation (α = .85), in the present study the SCS-SF showed good internal consistency (α = .87).

Objectified Body Consciousness. The Internal body orientation subscale of the Objectified Body Surveillance Scale (OBCS; McKinley & Hyde, 1996; Moya-Garófano et al., 2017). The Body Surveillance factor of the OBCS scale has 8 items to be rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). If inversed, higher scores of the subscale correspond to greater “internal body orientation” (Homan & Tylka, 2014, p.101 ) or body functionality, which is focused on the body's physical capacities and internal processes (Alleva et al., 2015). The Spanish version of the subscale questionnaire showed adequate reliability (α between .68 and .73). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for body surveillance was acceptable (α = .77).

Body Appreciation. The Body Appreciation Scale-2 (BAS-2; Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015; Swami et al., 2017). The BAS-2 measures an individual's acceptance of the body, respect for, and positive opinions towards her/his body. Its 10 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = always). As in the Spanish validation (α = .94), in the present study the BAS-2 showed excellent internal consistency (α = .94).

Body Compassion. The Body Compassion Scale (BCS; Altman et al., 2020; Spanish translation conducted by the authors). The BCS assesses the feeling of self-compassion towards one's own body: (1) Defusion (e.g., “When I notice aspects of my body that I do not like, I get down on myself”), (2) Common Humanity (e.g., “When I am concerned if people would consider me good-looking, I remind myself that most everyone has the same concern.”) and (3) Acceptance (e.g., “I am accepting of my looks just the way they are.”). BCS consists of 23 items to be rated on a Likert scale (1 = almost never; 5 = almost always), with total scores ranging from 23 to 115. In the present study, participants completed a Spanish translation of the BCS obtained using the parallel back-translation procedure. A bilingual translator not affiliated with the study translated the obtained items from English to Spanish until obtaining full consensus among the authors. The original version of the questionnaire obtained good results in terms of validity and reliability, showing excellent internal consistency for the total score (α = .92) and the subscales (Defusion: α = .92; Common Humanity: α = .91; Acceptance: α = .87). The BCS was translated into Spanish using the forward and backward translation technique. Two separate multilingual specialists translated the BCS into Spanish while retaining the semantic equivalence between English and Spanish during the procedure. The back-translated version was always edited in accordance with the original theoretical definition of each of the scale's dimensions taking into consideration the principles of content validity. The final version of the questionnaire was translated into English by an expert translator. All the authors of this article evaluated and approved the back-translated version. The Spanish validation of the BCS can be found at https://osf.io/fpu6t/.

BI-Focused Shame. The Body Image Shame Scale (BISS; Duarte et al., 2015; Spanish translation conducted by the authors). The BISS is a 14-item instrument, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never; 4 = almost always), designed to measure BI-focused shame and its phenomenology. This measure includes two subscales: external BI shame, and internal BI shame. The BISS's global score reliability was found to be excellent in the original version (α = .92), as well as for the internal (α = .92) and external (α = .90) BI shame. In the current study, Cronbach's alphas were also adequate (α = .93 for the total score; α = .89 for the internal BI shame; α = .88 for the external BI shame). The translation of BISS to Spanish was carried out as a part of its validation, following the same aforementioned steps as the BCS (Altman et al., 2020).

Procedure

The sample was recruited from the general population. Self-report measures were presented in online and paper-and-pen forms depending on the provenance of the sample. The measures were not filled out in the presence of the authors. Online forms were provided as a link to the online survey portal “LimeSurvey”.

Part of the sample (n = 100) was recruited from a Laboratory for Research in Behavioral Experimental Economics (LINEEX) online platform, which works as a pool recruitment service that provides opportunities to complete online questionnaires for monetary compensation. Interested participants were directed to an online link and, after its completion, were paid 5 euros. Other participants (n = 188) were recruited from the University of Valencia, as well as social networks. By taking part in the study, these participants entered a raffle for 3 gift experience boxes (valued at 30 euros each). Hence, we did not expect differences across two different samples as both received a reward. Moreover, to control the potential error associated with careless or nonsensical responses, four “attentional control questions” were inserted following Tylka and Wood-Barcalow's (2015) procedure.

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the software SPSS v.26. Descriptive analyses were carried out to examine sample demographics. Univariate normality was examined by the Skewness and Kurtosis (West et al., 1995), which indicated that there was no severe violation of the normal distribution (Kline, 2005). To test the construct validity, Pearson correlation tests were conducted among Spanish versions of BCS, SCS-SF, and BMI. In addition, we assessed the nomological validity of the BCS considering the Objectification Theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) and the relationships found in the literature between BC, body appreciation, the internal orientation of OBCS, body shame, and self-compassion (e.g., Alleva et al., 2020; Homan & Tylka, 2014) through Pearson's correlations.

Furthermore, the explorative factor analysis (EFA) was performed to determine the factorial validity of the BCS using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity. Cronbach's alpha was used to determine the internal consistency reliability of the BCS.

The hypothesized relationships between the variables (BC, body appreciation, body shame, and risk of ED) were analyzed using the PROCESS function, V3.5, in IBM SPSS, V.28 (Hayes, 2018). First, PROCESS model 81 was used to estimate serial-parallel mediation effects while including age and BMI as covariates. Nonparametric analyses using 5,000 bootstrapped samples were applied to estimate 95% confidence intervals for indirect effects and mediational effects. This model allowed us to test the specific indirect effect of BC on the dependent variable (risk of ED) through body appreciation (as the primary mediator) and body shame (as the secondary mediator). As PROCESS requires complete data, only the sample that completed all the measures (n = 199) was included through the listwise deletion in the serial-parallel mediation analysis.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample

All the characteristics of the sample as well as the self-reported variables used to perform the exploratory factor analysis (n = 288) and the serial-parallel mediation model (n = 199) can be found in the Table 1. Besides the differences in the EDI-3-RF scores, there were no significant differences between the two samples (see Table S1 at https://osf.io/fpu6t/).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Anthropometric Characteristics of the Participants

| Exploratory factor analysis (n = 288) | Serial-parallel mediational model (n = 199) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | M(SD) | % | M(SD) | |

| Age | 24.65(5.03) | 24.87(5.21) | ||

| BMI | 21.94(2.89) | 22.14(2.95) | ||

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 7.29 | 6.53 | ||

| Normal weight | 77.08 | 75.38 | ||

| Overweight or obese (BMI > 25) | 15.62 | 18.09 | ||

| Country of birth | ||||

| Spain | 94.79 | 93.97 | ||

| Othera | 5.2 | 6.03 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 86.1 | 85.4 | ||

| Married/partnered | 13.2 | 18.6 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 0.7 | 0 | ||

| Highest educational level | ||||

| Middle school | 23.6 | 21.1 | ||

| University/vocational training | 45.8 | 47.2 | ||

| Master's degree | 28.1 | 29.1 | ||

| PhD degree | 2.4 | 2.5 | ||

| Employment | ||||

| Unemployed | 9.7 | 11.1 | ||

| Student | 59.0 | 56.8 | ||

| Employed | 29.5 | 30.2 | ||

| Other | 1.7 | 2.0 | ||

| Self-compassion (SCS-SF) | 34.95(9.41) | 34.88(8.79) | ||

| Internal Body Orientation (OBCS) | 3.50(1.02) | 3.53(1.00) | ||

| Body Appreciation (BAS-2) | 3.47(0.81) | 3.64(1.20) | ||

| BISS | ||||

| Internal | 1.72(0.83) | 1.69(0.88) | ||

| External | 1.21(0.78) | 1.10(0.82) | ||

| Total | 1.47(0.77) | 1.39(0.81) | ||

| BC (BCS) | ||||

| Defusion | 28.50(7.76) | 28.59(7.76) | ||

| Common Humanity | 24.28(7.57) | 23.68(7.90) | ||

| Acceptance | 17.76(4.83) | 17.65(4.81) | ||

| Total | 70.54(14.33) | 69.92(13.99) | ||

| Body dissatisfaction (BSQ) | 83.30(34.99) | 83.40(35.11) | ||

| Risk of ED (EDI-3-RF) | 24.24(19.64) | 28.55(20.05) |

Note. BMI = Body Mass Index; SCS-SF = Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form; OBCS = Objectified Body Consciousness Scale; BAS-2 = Body Appreciation Scale-2; BISS = Body Image Shame Scale; BC = Body Compassion; BCS = Body Compassion Scale; BSQ = Body Shape Questionnaire; EDI-3-RF = Eating Disorders Inventory-3 Referral Form.

a Percentage of participants answering that they came to Spain when they were less than 7 y.o.

Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Adaptation of The Body Compassion Scale (BCS)

The KMO = .91 exceeded the recommended value of .60 (Kaiser, 1974), and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity, χ2(253) = 4188.09, p < .001, revealed that the data were appropriate to perform an EFA. Parallel analysis (Horn, 1965), using a macro for SPSS (O'Connor, 2000), determined that three factors should be retained. Items with communalities less than 0.2 were excluded from the EFA (Munro, 2005). The maximum likelihood factorial rotation with three factors using oblique rotation “oblimin” was carried out, accounting for 61.41% of the total variance. The factorial solution showed that all the items had minimum factor loadings above ≥ 0.40, and the derived factors were labeled based on Altman et al. (2020) : (1) Defusion; (2) Common Humanity; and (3) Acceptance (see Table 2). Skewness and kurtosis for all the items are shown in Table S2 of the Supplemental Materials (see https://osf.io/fpu6t/).

The internal consistency of the BCS was good for the total score (α = .89) as well as for Defusion (α = .89) and Common humanity (α = .89); and excellent for the Acceptance subscale (α = .93). All subscales showed a strong significant positive correlation with the total BCS score. Moreover, regarding the subscales, Defusion showed a significant relationship with Acceptance, but a non-significant correlation was found with Common Humanity (r = .013; p = .830). Common Humanity correlated positively and significantly with Acceptance.

Regarding the construct validity, there was a significant moderate positive correlation between the BCS and the SCS-SF. The relationship between the BCS and the BMI was significant, showing a weak significant negative correlation. As regards the nomological validity, Defusion and Acceptance subscales were significantly correlated with the OBCS internal body orientation subscale, and the SFS-SF, the BAS-2, and the BISS. The Common Humanity subscale correlated significantly with the SFS-SF and the internal orientation subscale of OBCS. The BCS total score correlated significantly with all the measures. Moreover, the Common Humanity subscale significantly correlated positively with internal body orientation (r = .14; p = .021). However, no significant associations were found between BI measures (BISS, the internal body orientation of OBCS, and the BAS-2) and the Common Humanity subscale. The complete table of correlations can be found in Table S3 of the Supplemental Materials (see https://osf.io/fpu6t/).

The BCS total score (M = 70.54; SD = 14.33) was similar to the Altman et al. (2020) study. Furthermore, BCS (vs. SCS-SF) showed stronger correlations with the positive BI dimensions (i.e., internal body orientation and body appreciation) and were negatively associated with the negative BI dimensions (e.g., body shame).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for all the items of the BCS and Standardized Factor Loadings and Communalities of the Exploratory Factor Analysis with a Three-Factor Structure

| BCS ítem | M(SD) | Factor loading | h 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defusion | Common Humanity | Acceptance | |||

| Factor 1: Defusion / Defusión | |||||

| Item 1(R) | 3.45(1.09) | .69 | .53 | ||

| Item 2(R) | 3.34(1.14) | .68 | .63 | ||

| Item 3(R) | 3.31(1.17) | .71 | .51 | ||

| Item 4(R) | 3.10(1.19) | .78 | .63 | ||

| Item 5(R) | 2.81 (1.12) | .77 | .53 | ||

| Item 6(R) | 3.33(1.25) | .41 | .39 | ||

| Item 7(R) | 3.69(1.16) | .60 | .29 | ||

| Item 8(R) | 2.75(1.15) | .59 | .57 | ||

| Item 9(R) | 2.73(1.24) | .50 | .53 | ||

| Factor 2: Common Humanity / Humanidad Compartida | |||||

| Item 10 | 2.55(1.14) | .64 | .43 | ||

| Item 11 | 2.75(1.15) | .73 | .54 | ||

| Item 12 | 2.60(1.16) | .77 | .58 | ||

| Item 13 | 2.88(1.09) | .55 | .44 | ||

| Item 14 | 2.81(1.22) | .75 | .54 | ||

| Item 15 | 2.70(1.14) | .89 | .77 | ||

| Item 16 | 2.57(1.09) | .85 | .69 | ||

| Item 17 | 2.92(1.10) | .52 | .31 | ||

| Item 18 | 2.51(1.16) | .59 | .36 | ||

| Factor 3: Acceptance / Aceptación | |||||

| Item 19 | 3.72(1.01) | .87 | .76 | ||

| Item 20 | 3.56(1.17) | .88 | .77 | ||

| Item 21 | 3.51(1.13) | .90 | .82 | ||

| Item 22 | 3.43(1.05) | .72 | .71 | ||

| Item 23 | 3.53(1.10) | .73 | .60 |

Note. BCS= Body Compassion Scale. N = 288. h 2= communality coefficient. Reverse-scored items are denoted with an (R).

The Protective Role of BC in the Risk of ED: The Mediational Role of Body Appreciation and Body Shame

The estimated direct effects between the variables in the serial-parallel mediation model are presented inFigure 2.

Note. BCS= Body Compassion Scale; BAS-2 = Body Appreciation Scale-2; BISS = Body Image Shame Scale; EDI-3-RF = Eating Disorders Inventory-3 Referral Form; BI = Body Image; ED = Eating Disorders. The dashed line represents nonsignificant effects. * p < .05. *** p < .01.

Figure 2. Model of the Mediational Effects of Body Appreciation and Body Shame in the Relationship Between BC and Risk of ED (n = 199)

Findings from the mediation analysis (Figure 2) showed that BC significantly predicted both external and internal BI shame, but did not have a direct effect on the risk of ED. However, the model indicated that the effect of BC on the risk of ED was fully mediated by body appreciation and internal body shame, as the indirect effects in Table 3 show. The indirect effect 4 “BC(external body shame(risk of ED” and the indirect effect 5 “BC(body appreciation(external body shame(risk of ED” were not significant. The total effect was also significant and the tested mediation model including all the variables explained 68.88% of the variance of the risk of ED, F(6, 192) = 70.82, p < .001. The detailed results of the mediation analysis can be found in Table S4 of the Supplemental Materials (see https://osf.io/fpu6t/).

Table 3. Results for the Indirect and Total Effect of the Mediational Model

| b | SE | 95% CI [LL,UL] | |

| Indirect effects | |||

| Indirect effect 1: BC( Body appreciation ( Internal BI shame( Risk of ED | -0.18 | 0.04 | [-0.269, -0.109] |

| Indirect effect 2: BC(body appreciation(risk of ED | -0.17 | 0.07 | [-0.309, -0.043] |

| Indirect effect 3: BC(internal body shame(risk of ED | -0.16 | 0.05 | [-0.278, -0.070] |

| Indirect effect 4: BC(external body shame(risk of ED | -0.05 | 0.04 | [-0.139, 0.030] |

| Indirect effect 5: “BC(body appreciation(external body shame(risk of ED” | -0.04 | 0.04 | [-0.117, 0.029] |

| Total effect | |||

| Total effect model | -0.71 | 0.08 | [-0.856, -0.556] |

Note. BC = Body Compassion; BI = Body image; ED = Eating Disorders; X = independent variable; M = mediator variable; Y = outcome or dependent variable; b = the association between the mediator and dependent variable(s).

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was (1) to examine the three-factor structure of the Body Compassion Scale (BCS, Altman et al., 2020) in a sample of Spanish women from the general population; and (2) to test the protective role of BC on body shame and the risk of ED through body appreciation.

Regarding the BCS, the present study provides evidence for the validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the BCS, maintaining a three-factor solution with 23 items. The BCS constitutes a useful instrument to measure compassion towards one's own body in the general Spanish female population. Equally to the original validation (Altman et al., 2020) or the Italian validation of BCS (Policardo et al., 2022), the three subscales in the Spanish version were correlated to each other (except for the correlation between Defusion and the Common Humanity), as well as with the total BCS score. As in Van Niekerk et al. (2023) or Wong and colleagues (2022) , the results of the lack of correlation between the Defusion and Common Humanity factors indicate a lesser relationship between these two constructs. Regarding the body-specific measures, the Common Humanity subscale was also weakly or non-significantly correlated with positive and negative BI. Moreover, the case study of the BC-targeting intervention also has shown that only the effects on the Defusion and Acceptance (vs. Common Humanity) dimensions of BCS were maintained over time (Altman et al., 2017), showing the independence of Common Humanity from the other two dimensions. Given the above-stated, it can be established that the ability to attribute negative bodily experiences to a shared human condition does not seem to represent a prominent aspect when explaining BI disturbance (Altman et al., 2017; Van Niekerk et al.,2023).

Overall, the Spanish version of BCS showed good convergent validity and nomological validity. As expected, the scores of BCS had a negative correlation with BMI and a positive correlation with SCS-SF, as in the English or Chinese versions (Altman et al.,2020; Wong et al., 2022). Moreover, the Defusion and Common Humanity subscales were positively linked to positive BI dimensions associated with a kind and accepting attitude towards one's body and negatively associated with body-threat-related measures (i.e., body shame). Hence, in comparison to general self-compassion, the construct of BC appears to be closely related to the BI dimensions in line with the Italian or Australian versions (Policardo et al., 2022; Van Neikerk et al., 2023).

The second goal of this study was to develop an explanatory model for the protective role of BC on the risk of ED. The tested model accounted for 68.88% of the risk of ED variance. Particularly, the first hypothesis of the study was partially confirmed as BC was found to be directly associated with body shame (internal and external) in line with Altman et al. (2020) or Oliveira et al. (2018) ; however, it was not directly associated with a lower risk of ED. Thus, contrary to the direct protective role of general self-compassion on disordered eating and BI disturbance (Braun et al., 2016; Turk & Waller, 2020), current findings point out a mediating mechanism through which specific compassion towards the body may act on the decrease of the risk of ED.

Findings of the tested model point out body appreciation as a possible underlying mechanism that could explain the protective role of BC on the feelings of body shame and the risk of ED, supporting the second hypothesis of this study. Specifically, this model confirmed that the practice of BC may be associated with alternative ways of valuing oneself when facing body-related threats (e.g., Homan & Tylka, 2015). Therefore, while the perception of one's appearance inferiority has been associated with adverse self-evaluating emotional states (i.e., body shame) (Avalos et al., 2005; de Vries et al., 2016), the practice of body appreciation could promote the selection of more adaptive coping strategies (Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). In particular, the development of a kind relationship towards one's body (e.g., practicing compassionate attitudes towards oneself; receiving body acceptance from others), may promote the rejection of unrealistic societal appearance ideals (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015) and act as a protective factor against ED in women (Máximo et al., 2017).

Lastly, in accordance with the previous literature (e.g., Mendes et al., 2017; Oliveira et al., 2017), the tested model showed that BI-focused shame was strongly associated with higher levels of ED risk. Specifically, our results revealed that only internal shame (vs. external) was associated with the risk of ED. According to Duarte et al. (2015) , this dimension of body shame measures one's engagement in self-loathing/criticism as well as body concealment behaviors. Although the research on internal body shame is scarce, the association between shame and ED risk is consistent with the previous studies, where internalized shame predicted symptoms of bulimia nervosa (Troop et al., 2008) and was closely associated with self-criticism and ED (Duarte et al., 2014; Pinto-Gouveia et al., 2014). In all, our findings point out the need to distinguish the role of body shame dimensions in the development and maintenance of ED. Whereas external body shame is associated with other people's judgment of one's own appearance, internal body shame is focused inwards, on the internal affect regulation (Gilbert, 1998; 2014). Hence, it seems that maintaining the self-judgmental view of one's own body appearance (i.e., internal shame), and not receiving a negative evaluation from the social context (i.e., external shame), which appears to be closely associated with the risk of developing ED. Nonetheless, due to the novelty of this measure, further distinction on the role of body shame dimensions on ED risk is needed.

Overall, the results of the current cross-sectional study could be tentatively explained by the emotional regulation strategies they use. Previous studies have found that women that manifest more body self-criticism tend to be defensive and use unhealthy emotion-regulation techniques that, in the long term, could lead to maladaptive bodily and eating-related behaviors (Berking & Whitley, 2014). Conversely, women with high levels of compassion and body appreciation may choose more adaptive emotional strategies when facing body-related threats (e.g., Marta-Simões et al., 2016; Tylka et al., 2015), through the activation of the self-soothing system (Gilbert & Procter, 2006). Thus, future intervention programs should aim to cultivate compassion and appreciation specifically directed toward one's body (Prefit et al., 2019); for example, BC micro-interventions (e.g., brief self-guided exercises such as short videos or writing exercises focused on BC psychoeducation or writing a compassionate letter to one's body) have been shown to promote higher body satisfaction (Stern & Engeln, 2018). The compassion-focused therapy for ED (CFT-E) stands out as an effective approach in populations with high shame and self-criticism (Gilbert & Miles, 2014; Goss & Allan, 2014). CFT-E is based on the premise that disordered eating constitutes a set of non-adaptive strategies to regulate body-related threats (Goss & Allan, 2014). In this regard, our preliminary findings suggest that the established evidence-based techniques (e.g., CFT-E) could be complemented with additional techniques targeting specially BC in order to foster a higher body appreciation. The specific focus on BC may help to cope more effectively with the dysfunctional and distressful thoughts and feelings related to body image by promoting adaptive self-soothing regulation strategies (Gilbert & Miles, 2014; Goss & Allan, 2014). Nonetheless, further research on the protective role of BC should be carried out.

These results should be interpreted in acknowledgment of several limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional and correlational design impedes the establishment of cause-effect relationships. Therefore, although previous theoretical models support that compassion and body appreciation are the protective factors against body shame and ED (Carter et al., 2022; Turk & Waller, 2020) and that shame is an antecedent of the risk of ED (Braun et al., 2016), future research should include longitudinal and experimental designs to further explore these relationships. Additionally, the results must be interpreted with caution as the measure of BISS (Duarte et al., 2015) is not yet adapted to Spanish. Secondly, the sample of this study was non-clinical, participating in this study women from the general population. Further studies should broaden the age groups to include more female at-risk populations, such as children and adolescents (Treasure et al., 2020), as well as include men and populations with ED. Lastly, future studies should address other dimensions of positive BI, such as the appreciation of body functionality, in relationship with BC, as well as the use of BC attitudes as emotional regulation strategies of BI-related threats (i.e., activation of the self-soothing system through the fostering of feelings of safety or the general positive affect that could regulate the feelings of shame) (Gilbert & Miles, 2014; Odou & Brinker 2015).

In sum, this study indicates that the Spanish version of BCS is a reliable and valid assessment tool to be used in female non-clinical populations; the findings also underline the potential mediating mechanisms of the protective role of BC. The tested model, besides providing support for the unique contributions of the BI shame dimensions (internal vs. external) on the risk of ED, emphasizes the importance of promoting a kind, non-judgmental, and appreciative relationship with one's own body in ED prevention and treatment programs. Although future experimental research is required, these findings highlight the potential value of targeting BC and body appreciation for reducing internal body shame and, therefore, preventing the risk of ED.