Introduction

Externalizing behaviors have been defined as a series of maladaptive behaviors related to aggressiveness, delinquency, and/or hyperactivity in childhood and adolescence (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1984; Ang, Huan, Li, & Chan, 2016; Guerra, Ocaranza, & Weinberger, 2016; Ibabe, Arnoso, & Elgorriaga, 2014; Kann et al., 2016; Katzmann et al., 2017; Lee, Liu, & Watson, 2016; Ringoot et al., 2017; Samek, Goodman, Erath, McGue, & Iacono, 2016). Externalizing disorders are a significant phenomenon that is associated with minors' distress and that of people from their immediate social environment (family, friends, classmates). Thus, they have a negative impact on social, educational, professional, and other important areas (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Externalizing behaviors have been linked to multiple individual, genetic, or environmental variables, such as family, school, or community (Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, Van Ijzendoorn, & Crick, 2011; Kokkinos, 2013). Numerous studies have highlighted parental styles as one of the most important variables that influence children's neurological, psychological, and social development (Dehue, Bolman, Vollink, & Pouwelse, 2012; Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005). Fathers and mothers should love, protect, educate, guide, and teach their children in order to help them grow, develop, and prosper. In this regard, the work by Paquette and Bassuk (2009) describes that boys and girls who do not have the opportunity to develop tools for emotion self-regulation through positive parenting may develop problems of adaptation and functionality related to academic achievement, mental health, behavior problems, or social competence.

The scientific literature describes parenting styles from two perspectives: dimensional and typological. The dimensional perspective allows categorizing certain parental behaviors (such as affection, punishment, or control), whereas the typological perspective would include a constellation of those parental dimensions (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; O'Connor, 2002). The typological perspective is the most widely used because it allows a multidimensional approach, more appropriate for the study of parenting (Henry, Tolan, & Gorman-Smith, 2005; Mandara, 2003). In this sense, Baumrind (1967, 1971) distinguishes three types of parental styles as a result of the combination of the dimensions of affection and control: the authoritarian style, the authoritative style, and the permissive style. Maccoby and Martin (1983) divide the permissive style into indulgent style and negligent style. Thus, parents with an authoritarian style are characterized by a low level of affection and a high level of control, the authoritative style is characterized by a high level of both affection and control, the indulgent style is characterized by high affection but low control, and the negligent style is characterized by a low level of both affection and control.

Studies that explore the influence of different parenting styles and the development of externalizing behaviors found that the authoritative style is the only one that provides clear positive effects in a child's adaptation, promoting resilience, self-esteem, and a better psychological adjustment. In contrast, the other styles (authoritarian, indulgent, or negligent) place a child at risk of suffering externalization problems (Luk, Patock-Peckham, Medina, Belton, & King, 2016; Mestre, Tur, Samper, & Latorre, 2010; Oliva, Parra, & Arranz, 2008; Tur-Porcar, Mestre, Samper, & Malonda, 2012; van der Watt, 2014).

Some authors begin to be interested in fathers' and mothers' behavior separately, arguing that there is evidence that the association between parenting style and children's externalizing behaviors may vary as a function of parents' sex (Casas et al., 2006; Groh et al., 2014; Hart, Nelson, Robinson, Olsen, & McNeilly-Choque, 1998; Underwood, Beron, Gentsch, Galperin, & Risser, 2008). Moreover, it has been observed that the father's participation has a positive impact on the acquisition of greater cognitive capacity, increased empathy, and fewer stereotypical beliefs of a sexual nature. All these aspects, in turn, are related to lower rates of aggressiveness (Hoeve et al., 2009; Hoeve, Dubas, Gerris, van der Laan, & Smeenk, 2011).

With regard to gender, Lansford, Laird, Pettit, Bates, and Dodge (2014) noted the effect of the father on boys' externalizing behaviors. This could be explained from the perspective of the theory of roles (Hosley & Montemayor, 1997), in which boys are traditionally encouraged to be more independent and adventurous. In this sense, fathers can exercise their educational function more forcefully when interacting with their sons than with their daughters. Therefore, it could be stated that the father affects the child, and also, child's actions influence father's reactions. All this suggests that boys and girls could respond differently to their parents' behavior (Hipwell & Loeber, 2006; Laible & Carlo, 2004; Xu, Morin, Marsh, Richards, & Jones, 2016).

Given the interest in this subject, in recent years, many primary studies were carried out, creating the need to gather, synthesize, and analyze the available scientific evidence. The last published review we found is Hoeve et al.'s (2009) paper, so it is relevant to update it, given the proliferation of studies carried out since that date. On the other hand, most of the research has focused on the childhood stage, without taking into account adolescence, the stage with the highest prevalence of emotional or behavioral disturbances (Llorca-Mestre, Malonda-Vidal, & Samper-García, 2017; Medlow, Klineberg, Jarrett, & Steinbeck, 2016). These changes in adolescents also influence the relationship with their parents, which are adapted according to their needs. Luyckx et al. (2011), in a longitudinal study, report that the authoritative style is characterized by high levels of control and supervision at the beginning of adolescence, which progressively decline in late adolescence. The rest of the parental styles also show a decrease of control and supervision, though more dramatically. The reason for these changes is the fact that during middle and late adolescence boys and girls increase the time spent with their peers, to the detriment of time spent with their parents, in a process of seeking autonomy and independence (Bahr, Hoffmann, & Yang, 2005; Cutrín, Gómez-Fraguela, Maneiro, & Sobral, 2017; Smetana, Crean, & Campione-Barr, 2005).

Taking the above into account, the main objective of this systematic review is to evaluate the influence of parental styles on the development of externalizing disorders in adolescents. We shall also analyze separately paternal and maternal parenting practices and their effects according to children's gender. All the elements that might hinder the information obtained directly from parents and children (e.g., teachers or siblings), or that might intervene or influence their relationship (e.g., substance consumption) will be eliminated from analyses.

To meet this goal, the following research question is proposed: are adolescents' externalizing behaviors measured in terms of bullying behavior, delinquent and/or behavior problems, associated with received parental styles and adolescents' gender?

Method

To elaborate this systematic review, we followed PRISMA Declaration's guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Prisma Group, 2009).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were established: (a) the goal of the studies included was to determine the influence of parental styles on the development of externalizing behaviors; (b) the study population consists of adolescents aged between 10 and 19 years; (c) the studies must be primary studies and use a quantitative methodology; (d) the studies must have been published between 2010 and 2016.

Exclusion criteria were: (a) population with a diagnosis of mental disorder; (b) non-biological parent-child relationship; (c) studies involving relations between siblings or teachers; (d) works that deal with substance related disorder; (e) studies with a non-quantitative design; and (f) articles not published in Spanish nor in English.

Search Strategy

A systematic search in the following electronic databases was conducted: Medline, Cochrane, Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO, ERIC, and PsycARTICLES. The main descriptors used were Adolescent* AND parenting styles AND attachment AND school violence OR bull* behavior OR behave* problem OR conduct disorder, with 01/05/16 being the date of the last search.

Selection of Studies

Taking the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria into account, the selection of studies was carried out in two stages:

- In the first phase, two independent reviewers shortlisted articles based on the title and the abstract. The resulting list was subsequently agreed on by both reviewers, resolving any disagreements through discussion.

- In the second phase, the full text of the pre-selected studies was read by the two reviewers independently, developing a new list of potentially relevant articles, again resolving any discrepancies through discussion. If no agreement was reached, a third reviewer was asked to determine whether the study met the inclusion criteria.

The full texts of the papers finally accepted were carefully read, and their bibliographic references reviewed to identify possible relevant articles not located in the initial search. In order to reduce unplanned duplication of comments and provide transparency to the review process, as well as to minimize reporting bias, this study was recorded in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews, http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero) since its inception (Registry No: CRD42016045805).

Bias Risk Assessment

For critical reading, we used the systematic review checklist from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP; http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists), which was adapted to each of the studies reviewed (see Appendix A). Two independent reviewers assessed and compared each one of the accepted papers, describing the main characteristics, strengths, weaknesses, and limitations of each one. Following the works by Al-garadi, Khan, Varathan, Mujtaba, and Al-Kabsi (2016), Guevara, Criollo, Suarez, Bohórquez, and Echeverry de Polanco (2016), and Zeng et al. (2015), the following cut-off points were used: (a) 7 for the evaluation of cross-sectional studies; (b) 8 for longitudinal cohort studies; (c) 8 for longitudinal designs of cases and controls. Doubts and disagreements were resolved by consensus among reviewers, obtaining a high inter-judge reliability (Pearson correlation coefficient, kappa = .88, p < .001).

Tabulation and Data Analysis

Selected studies were coded in two summary tables depending on the type of design: cross-sectional or longitudinal (cohort and case and controls). The tables show the following results: research data (authors, year of publication, and nationality), main objective to be evaluated, participants' characteristics (sample size, gender, and age), evaluated outcomes (externalizing and parental behavior), and, finally, the main outcomes obtained. In the case of longitudinal studies, we have also included duration and follow-up time.

Results

Figure 1 shows the results in each of the stages of the review process. Applying the search strategy described, we initially located a total of 31,114 publications, to which 55 articles were added after reviewing the references. Subsequently 1,088 works were eliminated, as they were duplicates. Of the 30,081 remaining articles, when applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 150 publications remained for full text reading. In the next stage, 71 articles were selected, which underwent critical reading for their analysis of risk of bias, after which 54 studies were excluded for failing to meet the defined quality criteria. The process concluded with the selection of 17 articles that are part of this review, of which 13 are cross-sectional studies and 4 are longitudinal studies, with a total sample size of 27,792 adolescents.

Description of Studies

The cross-sectional studies included a sample of 18,481 adolescents and the longitudinal studies a sample of 9,311 adolescents. In most of the works the sample was homogeneous regarding gender. The age range was between 10 and 19 years, representing early, middle, and late adolescence. Three of these five longitudinal studies performed a prospective follow-up (cohorts). We found only one retrospective study conducted in Brazil, with a control ratio per case of 3:1 (CI 80-95%). A summary of the results is presented in Tables 1 (cross-sectional studies) and 2 (longitudinal studies).

Table 1 Summary of Cross-sectional Studies Examining Parenting Behavior and Externalizing Behavior

Note. AQ = Aggressiveness Questionnaire; AQ-C = Attachment Questionnaire for Children; BVS = Bullying Behaviors Scale; CEFC = Questionnaire of Evaluation of Family Communication; CES = School Climate Scale; DIAQ = Direct and Indirect Aggression Questionnaire; EA = Affect Scale; EBIPQ = European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire; ENE = Scale of Rules and Demands; ESPA29 = Parental socialization scale in adolescence; IPPA = Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment for Adolescents; PALS-Y = Portraits of American Life Study–Youth; PAQ = Parental Authority Questionnaire; PSI = Parenting Style Inventory; RSI = Relational Support Inventory.

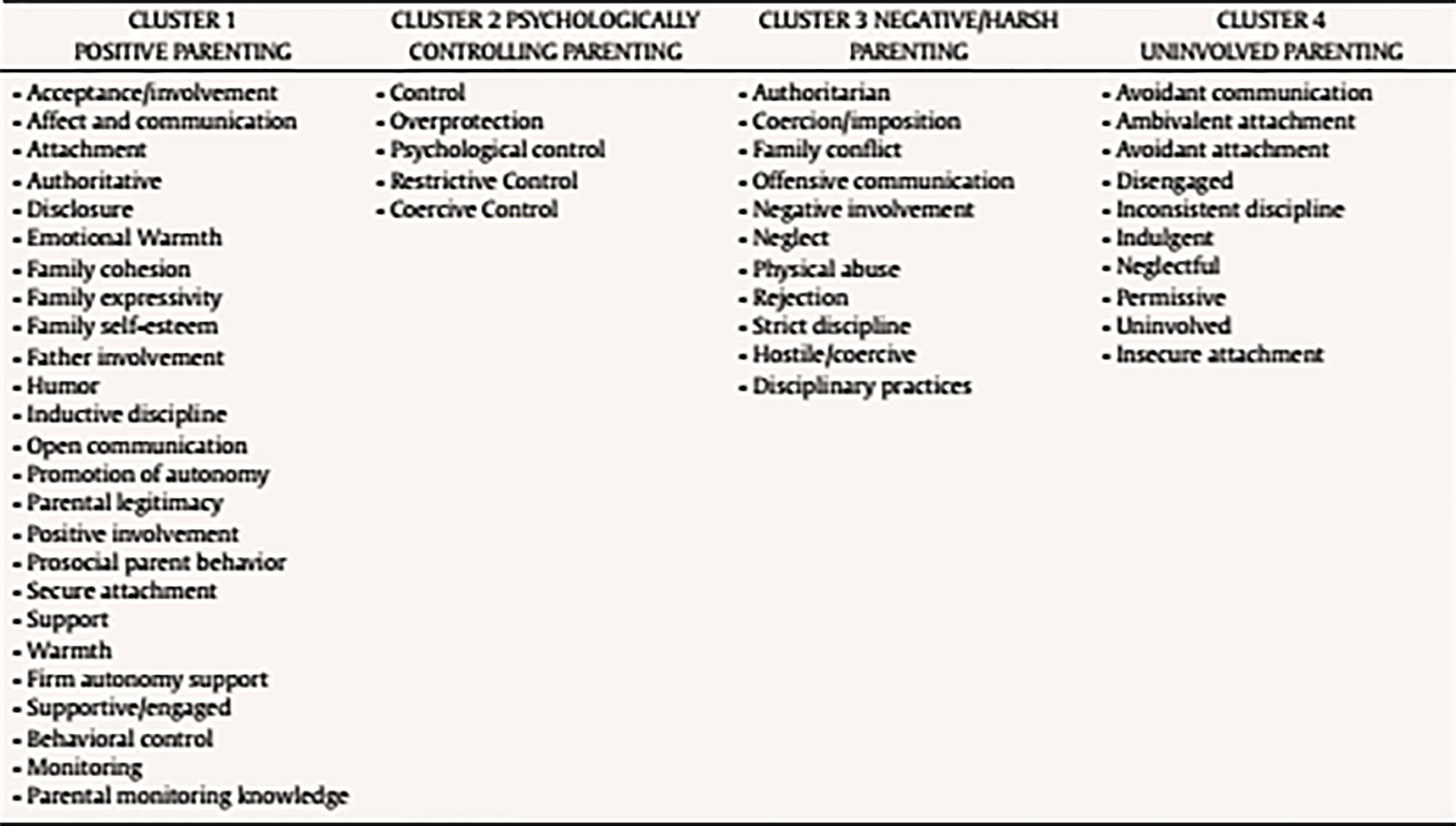

It must be taken into account that parental styles and externalizing variables were evaluated with different outcome measures. In the case of parental styles, the typological definition is the most widely used. However, in dimensional definitions it is necessary to carry out a system of grouping similar concepts to avoid dispersion of the outcomes. Based on the methodology of Kawabata et al.'s (2011) study, we describe findings according to these 4 clusters: “positive parenting”, “psychologically controlling parenting”, “negative or severe parenting”, and “uninvolved parenting” (see Appendix B). Due to the high heterogeneity observed in the outcome measures used by the selected studies, we decided to perform a narrative synthesis of the results, given the impossibility of conducting a meta-analysis.

Parenting Styles and Dimensions in the Development of Externalizing Behaviors

Consistently, the majority of research supports that the authoritative style has a protective effect on adolescent behavior. In this sense, Gracia, Fuentes, and Garcia (2012) also include the indulgent style as a protective factor. However, Martínez, Fuentes, García, and Madrid (2013) state that only the indulgent style provides more beneficial results.

In contrast, the authoritarian parental style is considered a risk (De la Torre-Cruz, García-Linares, & Casanova-Arias, 2014; Martínez et al., 2013; Trinkner, Cohn, Rebellon, & Van Gundy, 2012), along with the negligent style in the studies be Gracia et al. (2012).

The remaining publications analyze parental dimensions grouped into 4 groups to facilitate their reading. Thus, most of them associate “positive parenting” with lower percentages of externalizing behaviors, specifically at school. Within this group, the most valued dimensions are affection, communication, and autonomy. In contrast, children with conduct disorders describe their parents as being in the group of “negative or severe patenting” (Gómez-Ortiz, Del Rey, Casas, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2014; Gómez-Ortiz, Romera, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2016; Jiménez-Barbero, Ruiz-Hernández, Llor-Esteban, & Waschgler, 2016; Kokkinos, 2013; Pereira da Cruz Benetti, Schwartz, Roth Soares, Macarena, & Pascoal-Pattussi, 2014) followed by the group of “uninvolved parenting” (Gallarin & Alonso-Arbiol, 2012; Kokkinos, 2013; Salzinger, Feldman, Rosario, & Ng-Mak, 2011; Wolff & Crockett, 2011). As for parental control, Deutsch, Crockett, Wolff, and Russell (2012) describe parental supervision and control as preventive aspects, whereas other authors do not obtain firm results in this respect (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2014; Gómez-Ortiz, Del Rey, Romera, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2015).

Differences between Fathers and Mothers

In the revised studies, Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2015) found a greater frequency of the indulgent style in mothers and the negligent style in fathers in adolescents with externalization problems. Likewise, they considered that the most favorable situation for adolescents is for both parents to use the authoritative style. Jiménez-Barbero et al. (2016) stated that the maternal authoritarian style or the inconsistency between the parenting styles of the two parents are risk variables.

In accordance with these studies, Deutsch et al. (2012) and You, Lee, Lee, and Kim (2015) exclusively assessed maternal experiences and observed that strict maternal control, typical of authoritarian styles, as well as lax control, typical of negligent and indulgent styles, both are risk factors. In contrast, attachment and maternal emotional support are protective factors. Regarding school violence, Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2014) indicated the mother's affection and communication as well as the father's promotion of autonomy and psychological control as protective dimensions. In subsequent investigations by this same team, it was concluded that there are no differences in the role of father or mother (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2015).

In this review, some studies emphasize the role of father and argue that only the type of attachment with the father significantly predicts adolescents' aggressive behaviors (Gallarin & Alonso-Arbiol, 2012). Thus, father's support plays a protective role against adolescent involvement in violent acts and, at the same time, helps the children to value themselves more positively, both in the family and at school (Martínez-Ferrer, Musitu-Ochoa, Amador-Muñoz, & Monreal-Gimeno, 2012). Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2015) emphasize the importance of parental style, regardless of whether it is the father or the mother who exercises it. This study found that approximately half of the parents showed discrepant parental styles but if at least one of the parents had an authoritative style, the benefits appear to outweigh the risks associated with parental inconsistency.

Gender Differences in Adolescents

Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2014) observed that the most determinant factor for boys is father's moderate and sustained behavioral control, whereas for girls, it is mother's control. Thus, Jiménez-Barbero et al. (2016) notes that boys tend to rebel against maternal authority, whereas, on the contrary, they accept the father's authoritarian educational habits. These authors justify this by the effect of gender stereotype, which would induce boys' rejection of authoritarian maternal acts. De la Torre-Cruz et al. (2014) report that the most aggressive boys had verbally indulgent mothers; Varela-Garay, Ávila, and Martínez (2013), in contrast, report that girls with aggressive behavior had a less open communication with the father than boys.

Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2015) report that parents' psychological aggression towards boys and physical punishment of girls are related to behavior problems in children.

In a positive sense, Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2014) underline as protective factors the promotion of autonomy in boys, and the behavior of disclosure to parents (adolescents' tendency to inform them spontaneously about their activities outside home, their friendships or relationships) in girls. In 2015, this same team added affection and communication, or the promotion of autonomy in both sexes, and humor only in boys.

The study by Gallarin and Alonso-Arbiol (2012) only evaluates the effect of paternal attachment on aggression, without finding gender differences. In Kokkinos' (2013) or Martínez et al.'s (2013) studies, no gender differences were found between bullying and parental styles. These results indicate that risk factors associated with behavior are similar in both genders. Regarding longitudinal studies, none of them found significant results.

Discussion

This systematic review examines the influence of parental styles in the development of adolescents' externalizing behaviors. It also analyzes the possible differences between paternal and maternal parenting styles and their effects according to children's gender.

Parenting Styles and Dimensions in the Development of Externalizing Behaviors

The reviewed studies conclude that the authoritative parental style has a greater protective effect against the development of externalizing behaviors as revealed by numerous studies (Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, & Carrano, 2006; Hart, Newell, & Olsen, 2003; Luk et al., 2016; Rinaldi & Howe 2012). In this sense, Shayesteh, Hejazi, and Foumany (2014) argue that the positive stimulation that is typical of this educational style increases children's motivation to progress and attain their own identity. In addition, authoritative parents reinforce the autonomy of adolescents and strengthen healthy strategies in conflict resolution through supervision, support, and guidance. From a dimensional point of view, affection, communication, and autonomy promotion have the same beneficial effect, coinciding with previous studies (Gracia, Lila, & Musitu, 2005; Hasebe, Nucci, & Nucci, 2004; Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Oliva, Parra, Sánchez, & López; 2007; Rosa-Alcázar, Parada-Navas, & Rosa-Alcázar, 2014).

Some studies in European or Latin American countries support the indulgent parental style as beneficial (García & Gracia, 2009, 2014; Martínez et al., 2013). These authors argue that any non-positive behavior has a detrimental effect, and only affection based on acceptance, support, and reasoned communication promote appropriate behavior. In this line, numerous studies present in our review conclude that negative parenting styles of a hostile or punitive nature—typical of the authoritarian style—could hinder children's learning and regulation of negative emotions. Thus, children exposed to conflictive situations may be unable to adequately deal with their emotions and behaviors (Eisenberg et al., 2005). Regarding negligent style, the results in terms of development of externalizing behaviors are not as convincing as those found in the authoritarian style. However, lack of affection and supervision that are characteristic of this parental style have a negative effect on children's cognitive development and creativity. These children tend to be immature and rebellious, make decisions impulsively, develop low self-esteem, and are more dependent on adults (Shayesteh et al., 2014).

Table 2 Summary of Longitudinal Studies Examining Parenting Behavior and Externalizing Behavior

CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; IPPA = Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment for Adolescents; NHYS = New Hampshire Youth Study; PAQ = Parental Authority Questionnaire; PSI = Parenting Style Inventory; YSR = Youth Self Report

The studies included in this systematic review found contradictory results in the parental control dimension. On the one hand, most publications associate it with negative aspects such as coercion and constraint (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2014; Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2015). Consistent with these results, other studies add the fact that the most aggressive adolescents perceive their parents as controlling (Albrecht, Galambos, & Jansson, 2007; Oliva et al., 2007). However, our work includes a study that defends parental control as a protective factor against the development of externalizing behaviors in maladapted adolescents (Deutsch et al., 2012), which has also been supported in previous studies (Bacchini, Concetta, & Affuso, 2011; Hoeve et al., 2009). Pettit, Laird, Dodge, Bates, and Criss (2001) clarify these contradictions and point out that there are two types of parental control with very mixed results in adolescents. On the one hand, psychological control, also called restrictive or coercive control, involves a manipulation of children's emotional and psychological borders, frustrating their autonomy and self-development. Therefore, high levels of psychological control—characteristic of authoritarian styles—are related to adverse results in adolescents. This reasoning has been subsequently reinforced in other studies (Akhter, Hanif, Tariq, & Atta, 2011; Connell & Goodman, 2002; García & Gracia, 2009; Lee, Zhou, Eisenberg, & Wang, 2013; Rinaldi & Howe, 2012). In contrast, behavioral control or parental supervision is associated with the quality of communication between parents and children, in which parents guide and support the learning of family and social rules, protect the youth from negative emotional experiences, and provide them with the perception that there is someone who “cares about them and takes care of them” (Bacchini et al., 2011). Parental supervision—typical of authoritative styles—can therefore be interpreted as a positive behavioral strategy used as an instrument in the regulation of an adolescent's behavior (García & Gracia, 2009; McNamara, Selig, & Hawley, 2010; Oliva et al., 2007).

In the dimensional aspect, the authors reviewed consider coercive discipline and physical punishment, as well as inconsistent or uninvolved discipline, as risk dimensions. These results are consistent with previous meta-analyses (Connell & Goodman, 2002; Hoeve et al., 2009; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994). The meta-analysis performed by Kawabata et al. (2011) concluded that the “positive parenting” dimension was associated with a less relational aggression. On another hand, negative, severe, or uninvolved parenting is related to an increase of relational aggression.

Differences between Fathers and Mothers

Most studies to date were based on the notion that there are no great differences between fathers and mothers, since the true effect is produced by their type or characteristic parental dimension, regardless of whether it is exerted by the mother or the father (Achenbach, 1991; Stanger & Lewis, 1993). This same conclusion is reached in the study by Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2015) in the present review. However, studies are being published that highlight the effect of the parent-child dyad. In this line, we find several studies that indicate that attachment to the father (as opposed to the mother), versus other aspects, predicts adolescents' externalizing behavior, and also that father's role could influence the formation of adolescents' academic and family self-esteem (Gallarin & Alonso-Arbiol, 2012; Martínez et al., 2012). This difference was already documented by other authors, who relate father's figure to the management of affective states related to aggressiveness, as aggressiveness represents strength or power (Connell & Goodman, 2002; Fischer, Rodriguez, van Vianen, & Manstead, 2004; Liu, 2008; Rosa-Alcázar et al., 2014). In this line, Harper (2010) carried out a study at early stages (9-12 years), observing that the father's authoritative style promotes a decrease in externalizing behaviors, whereas the father's high psychological control promotes an increase in these behaviors.

Another aspect that both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies underline is the effect of discrepancy between parental styles. Our studies conclude that the most damaging effect is observed when neither of the parents uses an authoritative parental style (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2015; Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016). Other studies report that if at least one of the parents has an authoritative parental style the benefits seem to exceed the risk of parental inconsistency (Berkien, Louwerse, Verhulst, & van der Ende, 2012; Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2015).

Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2014) point to mother's affection and communication and the father's promotion of autonomy and psychological control as protective dimensions against school violence. These results may be related to the mother's role as caregiver in most families, emphasizing the importance of dimensions such as affection and communication.

In contrast, the father is the figure of power and authority, decisive in the acquisition of identity during adolescence. However, regarding the dimension of control, students involved in externalizing behaviors generally tend to perceive their parents as exerting more psychological control, although not necessarily true behavioral control.

Gender Differences in Adolescents

Most of the studies reviewed found a stronger bond between adolescents and their same-gender parent (De la Torre-Cruz et al., 2014; Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2014; Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016; Varela-Garay et al., 2013). One explanation could be that children tend to identify and copy the behavior of the same-gender parent (Hipwell & Loeber, 2006; Laible & Carlo, 2004; Lansford et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2016).

Moreover, the reviewed studies describe how certain parental practices of fathers, such as the use of psychological aggression in boys and physical punishment in girls, encourage violent behavior in their children (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2016). In contrast, parental dimensions like promotion of autonomy or humor in boys, and behavior of disclosure in the case of girls inhibit these violent behaviors (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2014). These results again suggest that the authoritative parental style protects against externalizing behaviors. This style, in the eyes of children, seems to stimulate their autonomy and promotes communication, humor, and disclosure (Oliva et al., 2008).

However, other studies maintain that the effects are quite similar for both genders (Gallarin & Alonso-Arbiol, 2012; Kokkinos, 2013; Martínez et al., 2013). Hence, no consistent conclusions were reached in this regard. These results could indicate that externalization depends on the lack of social skills rather than being a gender problem. Thus, Spence (2003) states that successful interpersonal problem resolution requires a sophisticated repertoire of social skills developed during childhood, adolescence, and youth. However, lack of adequate experiences in the environment, lack of correct social models, or certain interpersonal factors (management of impressions, grandiose sense of self-esteem, pathological lying, and manipulation for personal gain) could hinder such learning, promoting the use of externalizing behaviors as an alternative (Ometto et al., 2016). In accordance with these statements, previous studies suggest that social skills deficit is associated with externalization problems (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016; Shi, Bureau, Easterbrooks, Zhao, & Lyons-Ruth, 2012).

Conclusions and Limitations

Previous studies have confirmed that parents' behavior could affect adolescents' psychological health and social development, and even lead to externalizing behaviors in adolescence and adulthood.

Our study indicates that authoritative parenting styles or practices based on the promotion of affection, communication, or autonomy are clearly beneficial. However, the authoritarian style, based on the use of coercive practices, physical punishment, or imposition, pose a risk for the development of externalizing behaviors. On the other hand, we found less impressive results for indulgent (sometimes associated with positive effects) or negligent styles (sometimes associated with negative effects). As for parental control, it has been linked to beneficial effects if it is exerted as supervision or behavioral control by which parents guide their children during the educational process. In contrast, psychological, coercive, or restrictive control is associated with subsequent development of externalizing behaviors.

The possible differential effect of mother and father acquires increasing importance, due to the possibility that the father figure could be the most important source of future development of externalization. Fathers are increasingly involved in their children's education by participating actively in their care and protection, acquiring an important parenting role. Therefore, our findings suggest the need for further research on parenting styles of mothers and fathers in order to obtain a more complete view of family dynamics.

Another innovative aspect of this study concerns the modulating effect of gender on the development of externalizing behaviors in adolescence. In conclusion, we did not reach any robust results, as most studies do not take its influence into account. The few studies that consider it indicate that there is a greater influence between adolescents and their same-gender parents, and more so in boys, as noted in previous meta-analyses.

The main limitations of this study include the impossibility of performing a quantitative synthesis of results because of the heterogeneity of outcome measures and measuring instruments. However, the search strategy was restricted to articles published in English and Spanish, which could exclude interesting studies published in other languages. There also may be unpublished studies on the issue which could not be taken into account in this review. However, we made secondary searches in the reference lists of selected articles and attempted to contact expert authors in order to minimize potential publication bias. Finally, the fact that most of the studies obtained information from the perspective of adolescents or parents and that most of them used self-report questionnaires should be taken into consideration.

In spite of the limitations of the present study, some implications for practice can be established. Considering the importance of the socialization style exercised by parents at the onset of adolescents' externalizing behaviors, it would be interesting for future prevention programs of school violence or bullying to favor parents' involvement and orientation, as other authors (e.g., Besnard, Verlaan, Vitaro, Capuano, & Poulin, 2013) have argued. Moreover, this study underlines the importance of continuing to develop instruments that consider the specificities of parental styles and adolescents' gender. Lastly, the team responsible for this systematic review recommends performing multiple approaches to gather more information on parenting and, thereby, to design practical applications to help families.