Contribution to scientific literature

Currently there is a lot of information about mental health in college students, but only a little research with those who requested a psychological care service supported by their school. It’s relevant to generate knowledge about specific needs and recognize the importance of mental health promotion.

Introduction

The World Health Organization1 defines mental health as the well-being state in which the person develops his potential, coping life distress effectively, works productively, and can contribute to the community positively. This construct can be seen as a positive functioning perspective or through the assessment of negative conditions linked to a well-being decrease as was proposed by Headey, Kelley, and Wearing2 who affirmed thatmental health is integrated by 4 dimensions: life satisfaction, positive affect, anxiety, and depression.

The Quality of Life (QoL) is a positive health indicator and is defined as the person's perception about his/her life that includes assessment of physical health, psychological, level of independence, social relationships, environment and spirituality/religion/personal beliefs. The anxiety and depression disorders have been used traditionally for mental health diagnosis3, integrated by emotional, cognitive, physical and behavioral symptoms originated and maintained by social, family, genetic and personality factors4.

Comer5 states anxiety as a set Central Nervous System´s emotional and physiological responses derived from a perception of danger experienced in different ways. Depression is a deep sadness or hopeless feeling experienced beyond a few days duration that minimizes the functionality in the daily life6; it is a serious public health problem1 and is associated with a major suicidal behavior7 8-9).

The ideation, attempt, self-harm or death by suicide is a public health problem around the world, the suicidal behavior is a priority and universal challenge that can be avoided7,9 with assessment and adequate interventions. Approximately 800, 000 deaths by suicide occurred in 2016 and it is estimated that every forty seconds a person dies from suicide9-10. In Mexico the National Institute of Statistics and Geography11 reported 6,291 deaths by suicide in 2016, it implies 5.6 deaths out of 100,000 population. The same way it's projected that in 2020 this problem will determine 2.4% morbidity rate among countries with a market economy.

In summary, assessing the quality of life, anxiety, and depression is important to identify the mental health of a person and take evidence-based actions, promote the best clinical practices to optimize the well-being, and therefore minimize the risk of suicide among general population and samples in particular contexts such as the college students.

Materials and Methods

A sample of 145 students between 17-26 years old who answered the Informed consent and the instruments to asses mental health: a) World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire-BREF (WHOQoL-BREF) developed in 2014 by WHO and conformed by 26 likert type items that assess the perception about his/her quality of in four major domains: physical health, psychological, social relationships and environment that give a percent score between 0 to 100, so percentages below 50 often indicate problems and above are a good prognostic, had a Cronbach´s α=0.8912, b) Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) developed in 1988 and validated in 2001 by Robles and et al., conformed by 21 likert type items that assess anxiety symptoms and rank the results in minimal, mild, moderate and severe with Cronbach´s α= 0.8313 c) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) developed in 1988 and validated in 199814 conformed by 21 likert type items that assess depression symptoms and rank the scores in minimal, mild, moderate and severe with Cronbach’s α= 0.87. Finally, the answer to item 9 of BDI was used as a screening test for the suicidal risk, the answer options were: 0: I don't have any thoughts of killing myself, 1: I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out, 2: I would like to kill myself 3: I would kill myself if I had the chance.

Participants of the Study

A total of 145 clinical records of students who were in the process of individual psychotherapeutic care at the Psychological Care Clinic (CAP) of the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo (UAEH) between August 2014 and January 2015 were analyzed. The exclusion criteria were: i) canalized to group workshop ii) removed from the service by don´t follow the institutional lineaments iii) answered wrongly the instruments iv) had an uncompleted clinical expedient.

Procedure for Analysis

This has been analyzed in the CAP’s Psychometric Test Database to collect the user's information that requested psychological care and was assessed with WHOQoL-BREF, BAI, BDI, and an informed consent form. Through non-probabilistic sampling, the active users or those who completed the psychotherapeutic process were selected. All the statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS v. 23 to determine the relationship between variables and to know differences between groups of users with suicidal risk and without suicidal risk using Pearson’s and independent-samples T-test, respectively.

Results

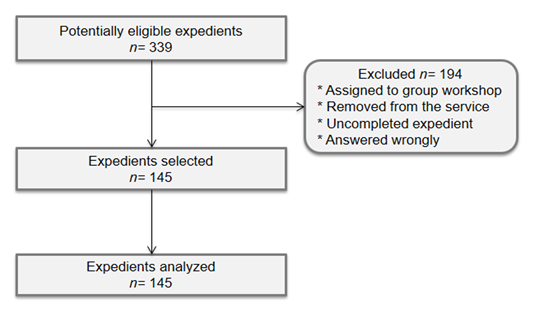

A total of 339 records of users enrolled in the CAP psychological care service were reviewed, 194 did not meet the inclusion criteria and only 145 were analyzed, Figure 1 shows the flow.

Participant’s flow

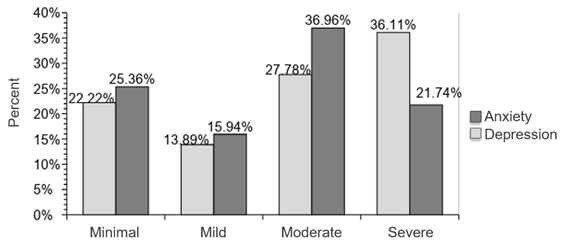

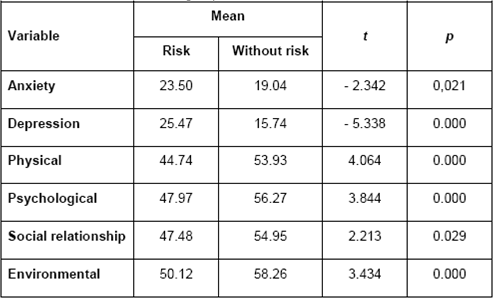

The sample was from 17-26 years old (M= 20.81, σ=1.9) 34.5% men and 65.5% women. The majority had from moderate to severe anxious and depressive symptomatology, 63.89% and 58.70% respectively (Figure 2). The quality of life results shows percentages below 50 only in physical health and slightly above in psychological, social relationship and environmental factors (Table 1). Furthermore, the screening test result indicates that 50.30% of users had a suicidal risk.

Anxiety and Depression

There were found medium positive and statistically significant correlations between anxiety and depression, and a negative correlation between both variables with all the quality of life factors, and it is possible to observe that their correlation becomes stronger with depression rather than with anxiety (Table 2). Differences between groups were also found, the users with suicidal risk reported more symptomatology of anxiety and depression as well as lower scores in all quality of life factors (Table 3). Besides, differences between sex groups were searched but not found.

Discussion

In Mexico, only 47.30% of people are satisfied with their life, 36.10% are moderate, 11.80% is just a bit and 4.8% are unsatisfied15. This satisfaction could be related with the quality of life perception and it gives meaning to this study results, especially regarding the high levels of anxiety and depression among college students and the correlation between both variables with quality of life factors found. Those results are similar to literature reported in university populations17 18 19 20 21-22. However, the results of anxious and depressive symptomatology are inconsistent with those reported in the WHOQoL-BREF because the scores, in general, are not observed below expected although there are specific cases in which the affectation is higher.

Also, we must emphasize that the sample was made up of users of mental health care services and this could mean stronger emotional support needs than the population that did not request the service. However, wit cannot be ruled out that many were unable to overcome access barriers such as office hours, an overload of academic activities, location in another institute, the admission process itself or stigma.

The epidemiological data shows that anxiety and depression are the most frequent mental disorders among population and the prevalence is highest in primary medical care16 and the university students are more vulnerable to poor mental health than general population by factors like academic stress, alcohol or other substance abuse, risky sexual behaviors, the appearance of a mental illness and socio-demographic conditions that increase the self-harm/suicide risk.

The study identified a negative impact on their mental health and clinical profile among college users and through the screening test we found half of them had suicidal ideation, and they seem to have a worse clinical profile regarding the variables evaluated compared to users without suicidal risk and this could mean that item 9 of the BDI is useful for early identification of those users most likely to commit suicide.

Considering the above, it is necessary to develop and implement effective institutional strategies in terms of mental health especially in suicide prevention. In fact, suicide prevention is a global priority and there are opportunities for prevention through opportune interventions in scientific based-evidence and with low economic cost23; accordingly, an integral and early evaluation of mental health is necessary and that include mental illness and positive health (actives and strengths) characteristics to obtain a complete diagnosis from population conditions. An example of an incomplete evaluation is possible to observe in the INEGI report about Mexican´s mental health24 in which statistics about death by suicide and feelings of depression are presented but was omitted positive indicators like psychological positive functioning, well-being or quality of life.

Farther the traditional focus in mental health must being others that the health as a process conformed by different dimensions, the diagnosis must be elaborated linking epidemiological indicators like: Healthy Life Years (HLY), Disability-adjusted life year (DALY), premature death, Health-adjusted Life Expectancy (HALE) and others to evaluate the quality of mental health practices in primary care and his correspondence with the international parameters established as: actions for mental health promotion and protection, detection and prevention of mental illness (such clinical guides use), structure and supplies for an adequate mental care, implementation of psychosocial disability programs, actions of human rights promotion and torture prevention.

Because the health-illness process is multilevel and multifactorial, the design and implementation of interventions should be done from an ecological perspective25, to can include all the population's risk and protective factors considering the social determinants in health26 and other complementary elements such as: justice, equality, empowerment27 as it is possible to view in Figure 3.

Community-based health intervention

The above implies that the design, implementation and impact evaluation of community intervention programs should be adequate to population which specific characteristics and a positive effect on risk and protective factors linked to suicide.

Like health, suicidal behavior is multifactorial and it is associated to protective and risk conditions as physical health, resources to commit suicide, use of alcohol and other substances, depression, social support, access to medical services, resolving skills or cultural and religious beliefs28. Accordingly, we have to individualize the users of the treatment using a complete evaluation and intervention plan based on the best clinical practices and the available evidence.

In addition, we want to highlight the number of deaths by suicide are part of negative results set of determining conditions as structural barriers or human rights violations for the variables directly related to mental health state including well-being or stigma and discrimination (and others) that increase the development of suicidal behaviors probability among a population's members must be considered. Due to the above, here we propose a map for the situational analysis, specific decision taking or intervention actions and general necessary recommendations that can help the responsible university authorities and interested academics better understand the problem and coping it effectively (Figure 4).

Mental health needs assessment for suicide prevention

Conclusions

The results showed that college student users of psychological care services have high anxiety and depression symptomatology and it is worse if there is suicidal ideation, which puts this population in a vulnerability condition and increases the probability of committing suicide. However the results of quality of life indicate that there is no affectation in the psychological area, so we must question whether it is appropriate to the WHOQoL-BREF instrument for this population or if any adaptation should be made to increase its sensitivity.

We consider the instruments used to assess anxiety, depression is an effective tool to determine the mental health and a clinical indicator of suicidal risk and allows to adopt immediately strategies. Furthermore in this care level is crucial to have trained staff and offer a service of quality based on evidence to increase the mental health and quality of life among students with clinical needs in vulnerable conditions.

We suggest future studies to use more instruments sensitive for suicidal behaviors as the Suicidal Risk Inventory29 and more research about mental health among university students in psychological care aim to determine and confirm our results and develop common institutional strategies for suicide prevention in this context.