Case Report

Cutaneous leishmaniasis in an albino child: a peculiar presentation

Leishmaniasis cutánea en un niño albino: una presentación peculiar

aFaculty of Medicine, University of Constantine-3, Algeria

bDepartment of Dermatology, University Hospital of Constantine, Algeria

cLMCVGN Research Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, University Setif-1, Algeria

dDepartment of Pediatrics, EHS Mère-Enfant, El-Eulma, Algeria

eDepartment of Pediatrtics, University Hospital of Setif, Algeria

Abstract

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is the most common form of leishmaniasis. It is characterized by nodulo-ulcerative skin lesions and occasionally nodular, papular/plaque, and/or impetiginous lesions on exposed parts of the body. However, other atypical lesions of CL have been reported worldwide such as lupoid, eczematous, erysipeloid, verrucous, dry, zosteriform, paronychial, sporotrichoid, chancriform, annular and erythematous volcanic ulcers. These non-specific lesions often make the diagnosis challenging due to the large number of differential diagnoses and may lead to a delay in the implementation of CL therapy and therefore a higher risk of lifelong scars and major quality of life issues and stigma. We report a case of an 11-year-old immunocompetent albino child boy that presented with 3 years' history of persistent multiple asymptomatic, small ulcers and cribriform scars of the forehead. Diagnosis of CL was confirmed by detecting Leishmania parasites in tissue specimens, and treatment by antimony drugs resulted in healing of lesion within one month. This is a novel case of a rare, atypical form of CL, which resulted in delayed diagnosis and management. Clinicians, especially those practicing in CL endemic areas like the Americas and the Mediterranean basin, should consider systematically the diagnosis of CL in front of long-lasting and/or non-specific lesions.

Keywords: Cutaneous leishmainasis; Albino; Child

Resumen

La leishmaniasis cutánea (LC) es la forma más común de leishmaniasis. Se caracteriza por lesiones cutáneas nódulo-ulcerosas y, en ocasiones, lesiones nodulares, papulares/en placas y/o impetiginosas en las partes expuestas del cuerpo. Sin embargo, a nivel mundial se han reportado otras lesiones atípicas de LC como úlceras lupoides, eccematosas, erisipelosas, verrugosas, secas, zosteriformes, paroniquiales, esporotricoides, chancriformes, anulares y eritematosas volcánicas. Estas lesiones inespecíficas a menudo dificultan el diagnóstico debido a la gran cantidad de diagnósticos diferenciales y pueden provocar un retraso en la implementación de la terapia LC y, por lo tanto, un mayor riesgo de cicatrices de por vida y problemas importantes de calidad de vida y estigma. Presentamos el caso de un niño albino inmunocompetente de 11 años de edad que presentó una historia de 3 años de evolución de múltiples úlceras asintomáticas persistentes, pequeñas y cicatrices cribosas en la frente. El diagnóstico de LC se confirmó mediante la detección de parásitos Leishmania en muestras de tejido, y el tratamiento con fármacos de antimonio resultó en la curación de la lesión en un mes. Este es un caso novedoso de una forma rara y atípica de LC, que resultó en un diagnóstico y manejo tardíos. Los médicos, especialmente aquellos que practican en áreas endémicas de LC como las Américas y la cuenca del Mediterráneo, deben considerar sistemáticamente el diagnóstico de LC frente a lesiones de larga duración y/o inespecíficas.

Palabras clave: Leishmaniasis cutánea; Albino; Niño

1. INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is the most common form of leishmaniasis [1]. In 2020, more than 85% of world's new cases of CL occurred in 10 countries, including Algeria as well as Brazil, Peru and Colombia [2]. Ulcerative skin lesions characterize CL and occasionally nodular, psoriasiform, and verrucous lesions on exposed parts of the body [1]. These lesions, mainly ulcers, leave life-long scars and serious disability and stigma [3]. Atypical lesions (such as erythematous volcanic ulcers and eczematous or erysipeloid lesions) may lead to a large panel of differential diagnoses [4].

We report a peculiar presentation of CL in an Algerian albino child, with a multiple cribriform ulcers and scars on the forehead.

2. CASE REPORT

An 11-year-old child boy with an unremarkable medical history apart from albinism was brought to our department for numerous tiny ulcers covering a large part of his forehead and glabella, persistent over the last 3 years despite many cycles of empiric antibiotic treatments. Physical examination revealed multiple asymptomatic, small and superficial ulcers with surrounding erythema and cribriform scars running from his middle forehead until the upper part of the nose (Figure 1). The underlying skin was infiltrated painless. His biochemical parameters were within normal limits, and there were mainly no signs of immunodeficiency syndrome. A history of staying in a leishmaniasis endemic area has been reported, and the diagnosis of CL has been confirmed by detecting Leishmania parasites in tissue specimens from skin ulcers via light-microscopic examination. Treatment by intramuscular injection of pentavalent antimony drugs at 10 mg/kg/day for a period of 15 consecutive days associated with oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/day for 5 days resulted in a clear regression and healing of ulcers within one month (Figure 2).

3. DISCUSSION

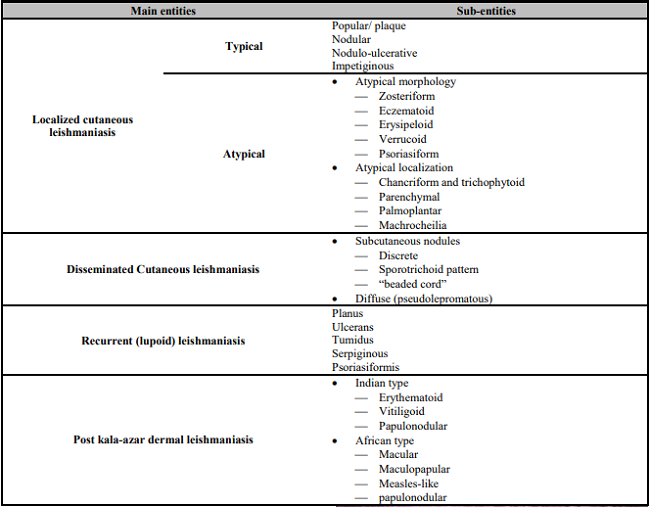

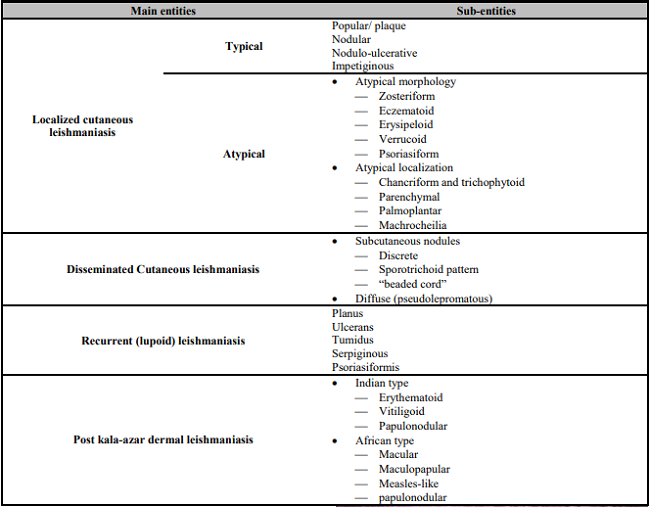

The leishmaniases are considered as a spectrum ranging from benign forms represented by CL to mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and systemic visceral leishmaniasis. Further, CL encompasses other entities including localized CL, disseminated CL, recurrent (lupoid) CL and post Kala azar dermal leishmaniasis (Table 1). Different peculiar lesions of CL have been reported worldwide [4]. They may display various aspects, such as lupoid, eczematous, erysipeloid, verrucous, dry, zosteriform, paronychial, sporotrichoid, chancriform, annular and erythematous volcanic ulcers [5]. Our patient presented a rare, atypical form of CL with a number of superficial tiny ulcers and scars, and the affected area appeared as a “cribriform” plaque. Often, these atypical forms of CL are misdiagnosed as blastomycosis, sporotrichosis, diverse fungal skin infections, cutaneous anthrax, eczema, lepromatous leprosy, tuberculosis, Mycobacterium marinum infections, basal and squamous cell carcinomas, and even infected insect bites [4]; and this would result in delayed diagnosis and treatment, as in our case. The reason for this pleomorphism is still unclear, but it might reflect an underlying immune disturbance; and variations in parasite virulence and host factors have been hypothesized to modulate the CL presentation [4]. Our patient depicts only albinism, which is not an immune deficiency by itself.

Table 1: Classification of cutaneous leishmaniasis (adaptation of the classifications of Akilov et al [6]).

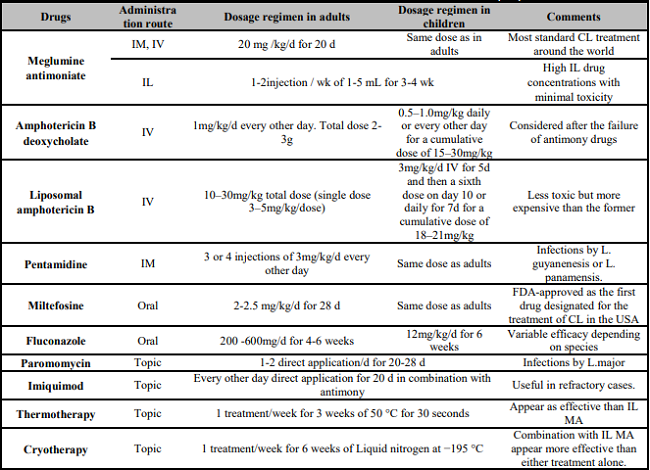

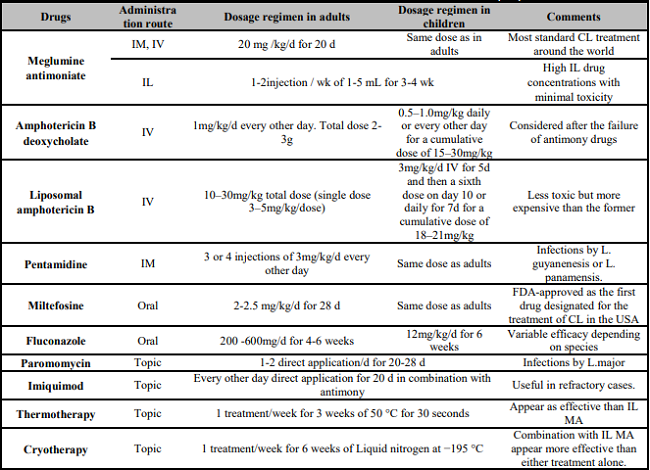

Treatment of CL differs according to infecting species, extent, location and progression of the disease. Usually, for limited infection when one or a few small lesions are present (excluding periorificial areas or over a joint) topical treatment could be proposed as the sole therapy. However, systemic therapy (mainly antimony drugs) should be used for more extensive lesions (Table 2).

Table 2: Treatments for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in adults and Children [7, 8, 9].

4. CONCLUSIONS

We report an exceptional clinical observation of CL with a multiple cribriform ulcers and scars on the forehead of albino child. Although, a large number of atypical morphological forms of CL have already been described, such presentation has not been reported in the literature before as far as we know. Thus, the healthcare professionals should perform the best diagnostic and treatment methods to lessen misdiagnoses and control disease progression. Physicians, especially those practicing in CL endemic areas like the Americas and the Mediterranean basin, should bear in mind that the disease may present with various clinical features and even unexpected aspects.

REFERENCES

1. Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(9):581-96. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70209-8.

[ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed Nov 2022).

[ Links ]

3. Bennis I, De Brouwere V, Belrhiti Z, Sahibi H, Boelaert M. Psychosocial burden of localised cutaneous Leishmaniasis: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):358. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5260-9.

[ Links ]

4. Meireles CB, Maia LC, Soares GC, Teodoro IPP, Gadelha MDSV, da Silva CGL, et al. Atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;172:240-254. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.05.022.

[ Links ]

5. Jombo GTA, Gyoh SK. Unusual presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis in clinical practice and potential challenges in diagnosis: A comprehensive analysis of literature reviews. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2010;3(11):917-21. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(10)60220-9.

[ Links ]

6. Akilov OE, Khachemoune A, Hasan T. Clinical manifestations and classification of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(2):132-42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03154.x.

[ Links ]

7. Barba PJ, Morgado-Carrasco D, Quera A. Miltefosine to Treat Childhood Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113(8):827-831. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2020.11.033.

[ Links ]

8. Uribe-Restrepo A, Cossio A, Desai MM, Dávalos D, Castro MDM. Interventions to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis in children: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(12):e0006986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006986.

[ Links ]

9. Eiras DP, Kirkman LA, Murray HW. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Current Treatment Practices in the USA for Returning Travelers. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2015;7(1):52-62. doi: 10.1007/s40506-015-0038-4.

[ Links ]

© 2023 The Authors. Published by Iberoamerican Journal of Medicine