Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychology, Society & Education

versión On-line ISSN 1989-709X

Psychology, Society & Education vol.15 no.2 Córdoba may./ago. 2023 Epub 18-Mar-2024

https://dx.doi.org/10.21071/psye.v15i2.15798

Articles

Social networking activities, body dissatisfaction, beauty ideals and body appreciation in adult women

1 CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Argentine)

2 Universidad de Palermo, Buenos Aires (Argentine)

The aim of this research is to analyze the relationship between different types of social networking activities and body dissatisfaction, internalization of beauty ideals and body appreciation in adult women in the metropolitan region of Buenos Aires. The sample consisted of 121 women aged 18 to 65 (M = 36.59, SD = 12.59). Participants completed a survey on social networks, the EDI-2 Eating Behavior Inventory, the SATAQ-3 Questionnaire on beauty ideals and the BAS-2 Body Appreciation scale. A cross-sectional design was used. Pearson correlations were calculated indicating that a higher frequency of social media activities was positively associated with body dissatisfaction and internalization of beauty ideals and negatively associated with body appreciation. Posting transient status updates and checking to see what their contacts are doing were found to be the activities most associated with negative aspects of body image. The Macro Process was used to carry out mediation and moderation analysis. The results indicated that within the social networking activities, transient status updates had no direct effect on body dissatisfaction but there was a significant indirect effect through the mediating role of body appreciation. Age was not a moderator of this mediation. Body appreciation was shown to be a protective variable for body dissatisfaction towards certain activities in social networks in adult women.

Keywords: Mediation; Moderation; Age; Argentina

Social media have become an essential part of people’s daily lives, especially among young people (Auxier & Anderson, 2021) allowing individuals to be both consumers and producers of content (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). For example, users can selectively choose to join a group, share materials, post their own productions, and post status updates, videos, images, or tweets (Veldhuis et al., 2020).

A relevant aspect of the impact of social media is on body image. Body image involves an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and perceptions about their own body (Cash, 2004). Sociocultural theories (Thompson et al., 1999) have long demonstrated the influence of traditional media, such as cinema or television, on the internalization of thin ideals. The media are a source of pressure to follow these ideals and increase social comparison, resulting in body dissatisfaction among individuals, particularly women. Numerous more recent studies have found similar mechanisms with the use of social media (Roberts et al., 2022).

Studies and systematic reviews are consistent in indicating that higher participation in social media activities has a detrimental effect on body image and is associated with increased body preoccupation in both adolescent and young men and women (De Valle et al., 2021; Fardouly et al., 2018; Fioravanti et al., 2022; Rodgers et al., 2021; Rodgers & Rousseau, 2022; Saiphoo & Vahedi, 2019).

However, Holland and Tiggemann (2016) advised that investigating specific aspects of social media use may provide more useful information than analyzing the general use of social media, for example the number of hours spent on a particular platform. In this regard, different studies (Modica, 2019; Rodgers & Melioli, 2016) describe how seeking negative feedback through permanent updates, visual comparisons, and comments received are strong predictors of body image concerns and eating disorders (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Jarman et al., 2021b; Strubel et al., 2018).

There is evidence that age and gender play a moderating role in the impact of social media on body image, with adolescent girls and young women being the most vulnerable to negative effects (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Rodgers & Rousseau, 2022). However, several studies have indicated that the effect of social media on body image is mediated by the internalization of thin-ideals. It would be in cases of high internalization or high appearance related pressure that would lead to body dissatisfaction (Fardouly et al., 2018; Jankauskiene & Baceviciene, 2022; Jarman et al., 2021b).

So far, most studies have focused on preoccupation or dissatisfaction with body image, i. e. more on its dysfunctional aspects, but there is still a need for research that includes positive body image. Positive body image refers to the appreciation and acceptance of the unique characteristics, beauty and functionality of one’s own body (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015b).

There is evidence that body appreciation, the most evaluated aspect of positive body image, would function protectively against body dissatisfaction resulting from viewing images of more attractive peers on social media (Veldhuis et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). This moderating effect of body appreciation was verified in adolescents and young women (Andrew et al., 2016; Duan et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2020).

To date, no studies have investigated the impact of social media use on body image and the thin-ideal internalization in women with a broader age range that includes middle-aged women (30-65 years) (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). However, middle-aged women also experience body dissatisfaction and are judged in relation to an ideal of female beauty that emphasizes both youth and thinness (Grippo & Hill, 2008; Quittkat et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019).

An additional limitation is that most studies on social media use and body image have been conducted on young white women in developed countries, and there is a need to expand knowledge on this topic in other cultural groups (Rodgers & Rousseau, 2022), including Latin America, where research is scarce. Argentina is a Latin American country with mainly European roots. Previous studies have found that Argentinean adolescents, particularly girls, have a high internalization of thin ideals and a very low body appreciation compared to other Latin American adolescents such as those in Mexico and Colombia (Góngora et al., 2020). Given these particular cultural characteristics, it is an interesting group to analyze the use of social media and body image.

The aim of this research is to analyze the relationship between different types of social media activities and body dissatisfaction, the internalization of thin-ideals and body appreciation in adult women in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires.

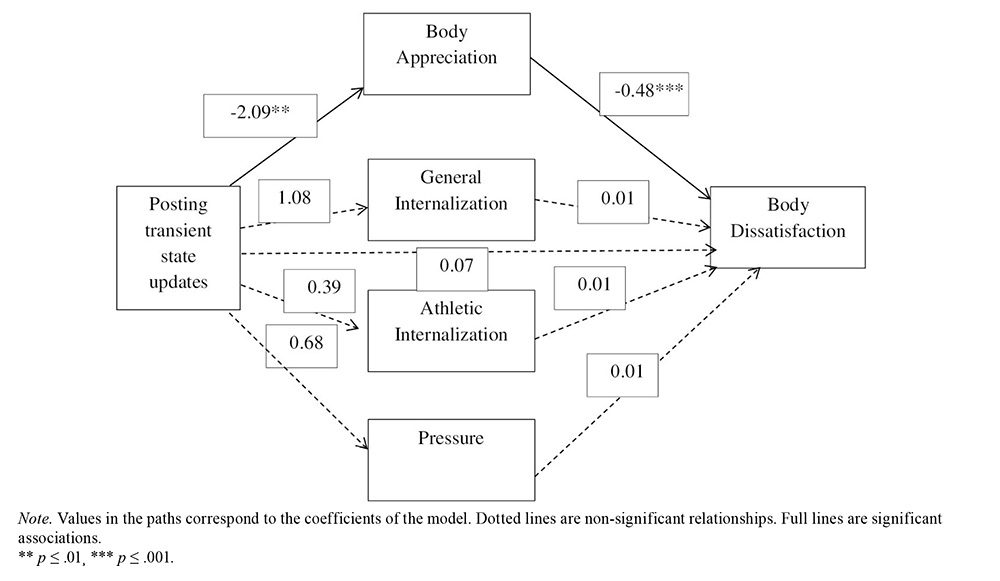

It is expected that the higher the frequency of social media activities, the higher the body dissatisfaction and that this relationship is mediated by the internalization of thin-ideals and body appreciation. The model presented in Figure 1 will be tested. Body appreciation has been found in several studies to moderate the relationships between social media activities and body dissatisfaction. The mediating role of body appreciation in this relationship will also be assessed. Age is also expected to have a moderating effect on the model tested, with the higher the age, the lower the relationship between the variables.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 121 women aged 18-65 years living in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires. The mean age was 36.59 years old (SD = 12.59), 63.6% (n = 77) were under 40 years old, and 36.4% (n = 44) were over 40 years old. A minority (9.1% of the participants) had primary education (n = 11), 54.6% (n = 66) had secondary education, and 36.36% (n = 44) had university level education. The mean B.M.I. was 24.11 (SD = 5.76). Concerning occupation, 23.14% (n = 28) were self-employed, 43.80% (n = 53) were employed, 9.91% were housewives (n = 12), 0.83% were unemployed (n = 1), 5.79% were retired (n = 7), and 16.53% (n = 20) did not work. Regarding the level of physical activity, the majority (58.68%, n = 71) exercised less than 3 hours per week, followed by 31.41% (n = 38) who practiced 3 to 6 hours per week, 8.26% (n = 10) between 7 and 15 hours per week, and 1.65% (n = 2) more than 16 hours of physical activity per week. Participation on the study was voluntary and anonymous. Regarding the time spent on social media, 3.3% (n = 4) used them for less than 5 minutes, 5% (n = 6) for 5 to 30 minutes, 13.2% (n = 16) for 30 minutes to 1 hour, 14.9% (n = 18) for 1 to 2 hours, 12.3% (n = 15) for 2 to 3 hours, 24.8% (n = 30) for 3 to 4 hours, and 26.5% (n = 32) for more than 4 hours.

Instruments

Social Media Use Survey. A survey was designed to gather information about the type of social media use. Different social media platforms were listed and participants had to indicate whether or not they used them and how often. The general frequency of use of all social platforms and the type of activities carried out on them were also assessed. Participants were presented a list of 17 activities (see table 2) with 5 response options: never (1) to very often (5). Items were taken from activities usually associated to active and passive social media use (e. g., Gerson et al., 2017) but without referring to a specific platform (Berri & Góngora, 2021; Castro Solano & Lupano Perugini, 2019).

Body Appreciation Scale -2 (BAS-2). It is a 10-item scale that assesses body appreciation through 5 response options: never (1) to always (5) (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015a). Validation studies of the scale in Argentina (Góngora et al., 2020) have demonstrated an adequate unidimensional factor structure, good convergent validity with measures of body dissatisfaction (r = -.72), pressure (r = -.49) and internalization of thin-ideals (r = .32 to r = -.61), as well as excellent levels of internal consistency (α = .96). In this sample, internal consistency was α = .94.

EDI-2 Eating Disorders Inventory. This 91-item instrument (Garner, 1991) assesses characteristics associated with eating disorders. It has three disorder-specific subscales (Drive for Thinness, Bulimia, and Body Dissatisfaction) and the remaining eight scales correspond to associated traits. For this study, only the Body Dissatisfaction scale was used. The instrument has been validated in Argentina. The scale has shown evidence of validity to discriminate between clinical and general groups, men and women, and between different age groups. In the validation studies, the internal consistency of the specific scales were α > .80 (Casullo et al., 1996; Casullo et al., 2000). In the sample of this study the internal consistency was α = .84.

Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ-3). This instrument consists of 30 items assessing four dimensions of sociocultural influences on body image (Thompson et al., 2004): Information, Pressure, General Internalization, and Athletic Internalization of thin-ideals. The items are answered on a 5-option Likert scale: from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Validation studies conducted in Argentina have found adequate indicators of construct validity in women with and without an eating disorder, concurrent validity with the EDI-3 scale (r = .20 to r = .50), and internal consistency (α = .82 to α = .92) (Murawski et al., 2015). For this study, the subscales Pressure, Internalization-General, and Internalization-Athletic were used. Internal consistency in this sample was α = .85 for Pressure, α = .79 for Internalization-General, and α = .73 for Internalization-Athletic.

Procedure

A cross-sectional design was used in this study. Instruments were completed in an online format through a link to Google Forms. Psychology students from the University of Palermo participated in the dissemination of the research through social media and contact with potential participants as part of their research practice. Participants were informed of the purposes of the research, the confidentiality of the data, and their right to refuse to participate and withdraw from the research at any time. They signed an informed consent form before completing the questionnaires. This research complies with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association (2010) and the national standards for scientific research and from the University of Palermo. Given the characteristics of the research, voluntary and anonymous participation of consenting adults in non-intervention studies, it was tacitly approved by an internal ethics committee at the Department of Psychology, University of Palermo.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS.24. The descriptive data, skewness and kurtosis of the measures used were analyzed. The values of skewness ranged between -.60 and .50, while the values of kurtosis ranged between -.63 and -.18. There is a fair consensus that values between -2 and +2 indicate a normal distribution of the variable (Field, 2017), therefore, normality of the data was inferred.

A series of t-student tests were first performed to compare the means of the scales used in the study between participants over 40 years old and those under 40 years old. Cohen’s d was calculated as a measure of effect size of differences. Following the guidelines established by the author, an effect size d = .20 was considered as small, d = .50 as medium, and d = .80 as large (Cohen, 1992). Pearson correlations were calculated between types of social media activities and scores on the BAS-2, SATAQ-3, and the EDI-2 body dissatisfaction scale. Subsequently, the Macro Process (Hayes, 2017) in SPSS-24 was used to perform a mediation analysis (model 4), a moderation analysis (model 1), and a moderate mediation analysis (model 58) with the study variables. A mediation analysis assumes that the relationship between a predictor variable, in this case type of social media activity, and the dependent variable, body dissatisfaction, is reduced by including another variable as a predictor (body appreciation, internalization of thin-ideals, and the pressure perceived from those ideals). Mediation would indicate that the relationship between these two variables is “explained” by a third variable (the mediator). Mediation is tested by assessing the indirect effect size and its confidence interval. If the confidence interval contains zero, it is assumed that there is no genuine mediation effect. If the confidence interval does not contain zero, it is concluded that mediation has occurred. In this study a 95% confidence interval was used and conducted the analysis with a bootstrap of 5000 samples to reduce bias (Field, 2017). A moderation analysis occurs when the relationship between two variables changes as a function of a third variable. In this case, the relationship between social media activity and body dissatisfaction could change as a function of body appreciation values. Moderation occurs if there is a significant interaction between the predictor and the moderator (Hayes, 2017). Moderate mediation assesses whether there is a significant moderator in the path between the predictor (social media activity) and the mediator (body appreciation) or in the path between the mediator and the outcome variable (body dissatisfaction). In this case the moderator assessed was age. Moderate mediation is considered to be present if in either of these two paths there is an interaction between the predictor and the moderator (path a), or between the mediator and the moderator (path b) (Hayes, 2017).

Results

Correlations between social media activities, body dissatisfaction, thin-ideal internalization and body appreciation

Means and standard deviations of the BAS-2, EDI-2 Body Dissatisfaction and SATAQ-3 subscales are presented in Table 1.

Given the wide age range of participants, scale means were compared between women over 40 years old and women below 40. It was found that there were no significant differences in Body Dissatisfaction (t = -.76, p = .44, d = -.14), Body Appreciation (t = -1.9 p = .07, d = -.36), Internalization- General (t = 1.8, p = .07, d = .34), and Internalization-Athletic (t = 1.6, p = .1, d = .30), and Pressure (t = 1.8, p = .07, d = .34) between the two age groups. There was also no difference in time (t = .58, p = .58, d = .11) spent on social media between the two groups. Given the sample size of the subgroups and the lack of significant differences in the measures between them, the whole group was analyzed together.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of the study variables and Pearson correlations between social media activities, the SATAQ-3 subscales, the BAS and the EDI-2 Body Dissatisfaction subscale

| Activity | BAS | Pressure | IntG | IntA | BD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post permanent status updates | -.28 | .13 | .11 | -.01 | .25 |

| Post transient status updates (24hrs) | -.39** | .32* | .22 | .29* | .45*** |

| Commenting (on statuses, posts, photos) | -.28 | .21 | .23 | .18 | .33* |

| Share/repost photos, news/videos | -.11 | -.10 | .05 | -.25 | .05 |

| Chat | -.02 | -.03 | .01 | .06 | -.07 |

| Check to see what my contacts are up to | -.13 | .16 | .49*** | .26 | .08 |

| Create or confirm an event | -.15 | -.03 | .09 | .04 | .13 |

| Post photos | -.15 | .01 | .16 | .05 | .23 |

| View photos | -.07 | .06 | .21 | .10 | .08 |

| Tag photos | -.26 | .12 | .20 | -.03 | .21 |

| Post videos | -.39** | .08 | .28 | .01 | .23 |

| Tag videos | -.06 | .23 | .32* | .11 | -.08 |

| Upload stories (Instagram) | -.15 | .24 | .19 | .20 | .21 |

| Making live broadcasts | -.04 | -.06 | -.01 | -.06 | -.20 |

| Passively surfing the web - “scrolling” (not commenting, liking or tagging anything) | -.16 | .05 | .05 | .13 | -.18 |

| Actively surfing the web (commenting, posting or “liking” posts, images, etc.). | -.08 | -.22 | -.02 | -.11 | .22 |

| View profiles of my friends/contacts | -.16 | .04 | .17 | .08 | .09 |

| M | 36.47 | 16.34 | 21.51 | 12.57 | 12.40 |

| SD | 9.12 | 7.22 | 7.83 | 5.01 | 6.45 |

Note. IntG = Internalization-General, IntA = Internalization-Athletic; BD = Body Dissatisfaction. * p≤ .05; ** p≤ .01; *** p≤ .001.

Pearson correlations were performed between the frequency of social media activities and the EDI-2 Body Dissatisfaction scale, the BAS-2 scale, and the SATAQ-3 subscales. The results are presented in Table 1. A mild to moderate positive association was found between the frequency of social media activities and body dissatisfaction, as well as a higher internalization of thin-ideals.

In relation to thin-ideal internalization, the most significant associations were linked to posting transient status updates, checking to see what my contacts are doing and tagging videos. Body dissatisfaction was significantly correlated with posting transient status updates and commenting (on statuses, posts, photos). Higher body appreciation was associated with lower frequency of social media activities, in particular, posting transient status updates and posting videos had the highest inverse correlations with this variable.

In summary, among the activities assessed, posting transitory status updates and checking to see what my contacts are doing were found to be the activities most associated with negative aspects of body image.

Mediation and moderation analysis

For a deeper understanding of the relationship between significant social media activities, body dissatisfaction, thin-ideal internalization, and body appreciation, a series of mediation and moderation analyses were conducted. Macro Process in SPSS-24 was used for this purpose. Transitory status updates was selected as the social media activity, as it was the activity previously found with the most significant associations with the study variables.

First, the relationship between transient state updates, body dissatisfaction, internalization of thin-ideals, and body appreciation was examined through Process model 4. This model allows assessing the mediating role of different variables in parallel. In this case, the mediating role of body appreciation and internalization of thin-ideals was assessed between social media activity and body dissatisfaction. The model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mediation model of body appreciation, internalization and pressure of thin-ideals in the relationship between transitory state updates and body dissatisfaction

Results indicated that transient state updates had no direct effect on body dissatisfaction (b = 0.07, p = .85), however, there was a significant indirect effect through the mediation of body appreciation (b = 1.01, 95% CI [ .18, 1.88]). Internalization of general thin-ideals (b = -0.004, 95% CI [ -.18, 19]), internalization of athletic-ideals (b = 0.0001, 95% CI [ -.18, .18]), and appearance related pressure (b = -0.009, 95% CI [ -.20, .16]) did not mediate the relationship between social media activity and body dissatisfaction. Body appreciation showed a protective effect against social media activity.

Given previous evidence regarding the moderating role of body appreciation between social activities and body dissatisfaction, this role was also assessed through the model 1 of Macro Process in SPSS-24. No interaction between social media activity and body appreciation was found in the studied sample in relation to body dissatisfaction (b = 0.01, 95% CI [-.07, .08], t = .13, p = .89). In this study, body appreciation plays a mediating, but not a moderating role with respect to body dissatisfaction.

Second, given the wide age range of the participants, the moderating effect of age was assessed in relation to the path between the frequency of transient state updates and body appreciation (b = 0.09, 95% CI [-.02, .21], t = 1.52, p = .21) and the path between body appreciation and body dissatisfaction (b = 0.001, 95% CI [-.006, .009], t = -.36, p = .71). Macro Process model 58 was used which tests for moderate mediation in which the moderator, in this case age, would have an effect on the path a and b of the mediation but not on path c with a direct effect on the dependent variable. No moderating effect of age was found in either of the two tested paths.

Discussion

Previous studies indicated that specific activities within social media were associated to greater body dissatisfaction (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). In this study, posting transient status updates was the activity most associated with thin-ideal internalization, body appreciation, and body dissatisfaction. To a lesser extent, checking to see what my contacts are doing was linked to the thin-ideal internalization. These activities involve not only spending a lot of time on social media but also being aware of others’ responses, which would favor social comparison (Fardouly et al., 2015; Tiggemann et al., 2018). Social media investment may be more important for body image than time spent on media (Verduyn et al., 2020).

It was also confirmed that some activities are associated with greater body dissatisfaction while others are associated with higher thin-ideal internalization. Although users can do different social media activities simultaneously, not all of them are followed with the same intensity. This creates a challenge in thinking about the assessment of social media activities because using a general measure of intensity of use across all activities can provide broader information about time and social media investment but it leaves out the specific activities that are associated with body dissatisfaction (Tylka et al., 2023).

Early studies on this topic have focused on the total connection time to social media or on the active-passive use of media, concluding that that this type of study has many limitations and that more precise information on social media use was needed (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Jarman et al., 2021b). In this study, the two most prominent activities correspond to an active use (posting transient status) and a passive use (checking what my contacts are doing). Both active and passive social media use were associated with lower body satisfaction and body appreciation, as well as higher overvaluation of shape and weight (Jarman et al., 2021a).

Analysis of the relationship of variables showed that transient state updating had no direct effect on body dissatisfaction but there was a significant indirect effect through the mediating role of body appreciation. A higher frequency of state updates would decrease body appreciation and this would be associated with higher body dissatisfaction. In this research, body appreciation has a protective role in mediating but not moderating the relationship between social media activity and body dissatisfaction.

It is interesting to consider whether body appreciation is a moderator, as if it were a stable trait, or a mediator, which is also affected by social media use. While many studies have taken it as a moderator, several other studies have found a link between higher social media activity and lower body satisfaction (Jarman et al., 2021b). New conceptualizations also allow us to think that a variable can be both moderator and mediator simultaneously (Karazsia & Berlin, 2018). It would be important to include body appreciation within theoretical models that account for the relationship of social media and body image. Although there is some research that supports parts of the existing theoretical models on body image (Tylka et al., 2023), the assumed relationships between the different variables need to be deepened and evaluated in further research.

Contrary to expectations, in the tested model, the internalization of general and athletic ideals as well as the perceived pressure of these ideals were not found to be mediators between social media activity and body dissatisfaction. This may be due to the fact that a specific type of activity such as transient state updates was selected, and this was an activity more associated to body appreciation but not to internalization or pressure of thin-ideals. It could be that other activities or the set of activities done in social media have a stronger link to the internalization of thin-ideals as other studies have found (Jankauskiene & Baceviciene, 2022; Jarman et al., 2021b).

On the other hand, age was not found to moderate the relationship of the variables in this mediation: both between transient state updating and body appreciation, and between body appreciation and body dissatisfaction. This research has included a large age group of women (18-65 years), a range that has not been assessed in other studies. The results would indicate that the relationship between the study variables affects all adult women in the sample equally, not just young women. Longitudinal research has found that body dissatisfaction remains stable across lifespan in women (Quittkat et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). However, it is striking that body appreciation tends to increase with age in women (Quittkat et al., 2019) so that some moderation by age might occur. In a meta-analysis, De Valle et al. (2021) also found no moderating effect of age on the impact of social media on body image. However, the limited number of studies with middle-aged women makes it difficult to compare results.

It should also be noted that the sample was composed of a higher proportion of young women (under 40), which may have an impact on the results. While all participants would use social media with a similar frequency, the type of platform may differ. Younger women have reported using more visual social media such as Instagram or TikTok, and being more active in media use (Fardouly et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2016). It would be necessary to extend the studies with an exclusive sample of older women to better assess the impact of social media activities on their body image or to analyze the results by age group. Other aspects of body image could also be incorporated, such as body functionality, which is also strongly related to women’s age (Alleva & Tylka, 2021).

Another aspect to consider in the relationship found between social media activities, body appreciation, and body dissatisfaction not moderated by age, could be the cultural group. Argentinean women have shown low body appreciation and high thin-internalization compared to other Latin American women (Góngora et al., 2020; McArthur et al., 2005). As a country with mainly European roots (Meehan & Katzman, 2001), several studies have pointed to a greater internalization of dominant European beauty ideals in the media. The large proliferation of cosmetic surgeries and cosmetic procedures in adult Argentinean women confirms the effort to achieve these ideals (International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 2022). Given these cultural characteristics, it is possible that adherence to Western beauty ideals and the pressure to maintain thinness and youthfulness may be persisted throughout adulthood and may not be something that primarily affects adolescent or young adult Argentinean women.

This research has some limitations. Although the sample is not small, a larger number of participants would be desirable in order to have more robust results. The participants belong mostly to a middle or upper-middle social class, with a high educational level in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, which could make the importance of thin-ideals more relevant in this social group. In addition, the sample does not represent the whole of the Argentinean population. The wide age range included in the sample (18-65 years), with different uses of social media and body concerns, should also be considered, so a more restrictive age range would have been preferable.

On the other hand, the instrument for assessing social media use is a survey designed for this purpose, which is usual for this type of research, but it is not a standardized questionnaire like the other instruments used. It would be important to make progress in the standardization of instruments on the use of social media so that the measures would be comparable between different research studies. In this study, we have inquired about types of social media activities without specifying the social platform. For example, visual social media such as Instagram have shown more association with body concerns than non-visual social media (Fardouly et al., 2018; Ridgway & Clayton, 2016). Future studies could assess activities by social platform and include exclusively visual social media.

Finally, the results of this study have highlighted body appreciation as protective of body dissatisfaction in relation to certain social media activities in adult women. Numerous studies have highlighted the protective and healthful role of body appreciation as being associated with increased well-being and protection from various types of disorders, including eating disorders (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Jarman et al., 2021b; Wang et al., 2020). Media alphabetization and positive body image promotion programs have shown promise in strengthening body appreciation and decreasing the negative effects of social media on body image (Rodgers et al., 2021; Rodgers et al., 2022; Tylka et al., 2023). The use of body-positive content on social media has also received emerging support as a way to mitigate body dissatisfaction (Paxton et al., 2022; Rodgers et al., 2022).

This research has contributed to the study of body dissatisfaction and social media use in middle-aged women. This is an age group that is under-represented in research (Rodgers & Rousseau, 2022) and is increasingly participating in social media. At the same time, it provides information on a different cultural group: Argentinean adult women. In sum, this study has attempted to contribute to the expansion of knowledge on social media and body image in a different age and cultural group in order to advance knowledge on this topic

REFERENCES

Alleva, J. M., y Tylka, T. L. (2021). Body functionality: A review of the literature. Body Image, 36, 149-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.11.006 [ Links ]

Andrew, R., Tiggemann, M., y Clark, L. (2016). Predictors and health-related outcomes of positive body image in adolescent girls: A prospective study. Developmental Psychology, 52(3), 463-474. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000095 [ Links ]

Auxier, B., y Anderson, M. (2021). Social media use in 2021. Pew Research Center. [ Links ]

Berri, P. A., y Góngora, V. C. (2021). Imagen corporal positiva y redes sociales en población adulta del área metropolitana de Buenos Aires. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(1), e-2398. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2398 [ Links ]

Cash, T. F. (2004). Body image: past, present, and future. Body Image, 1(1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00011-1 [ Links ]

Castro Solano, A., y Lupano Perugini, M. L. (2019). Differential profiles of internet users, personality factors, positive traits, psychopathological symptoms and life satisfaction. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica, 4(53), 79-90. https://doi.org/10.21865/RIDEP53.4.06 [ Links ]

Casullo, M. M., Castro Solano, A., y Góngora, V. C. (1996). El uso de la escala EDI-2 (Eating Disorders Inventory) con estudiantes secundarios argentinos. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Psicológica, 2, 45-73. [ Links ]

Casullo, M. M., Gonzalez Barron, R., y Sifre, S. (2000). Factores de riesgo asociados y comportamientos alimentarios. Psicología Contemporánea, 7(1), 66-73. [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1, 98-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783 [ Links ]

De Valle, M. K., Gallego-García, M., Williamson, P., y Wade, T. D. (2021). Social media, body image, and the question of causation: Meta-analyses of experimental and longitudinal evidence. Body Image, 39, 276-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.10.001 [ Links ]

Duan, C., Lian, S., Yu, L., Niu, G., y Sun, X. (2022). Photo activity on social networking sites and body dissatisfaction: The roles of thin-ideal internalization and body appreciation. Behavioral Science, 12(8), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080280 [ Links ]

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., y Halliwell, E. (2015). Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image, 13, 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002 [ Links ]

Fardouly, J., Willburger, B. K., y Vartanian, L. R. (2018). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media & Society, 20(4), 1380-1395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817694499 [ Links ]

Field, A. (2017). Discovering statistics using SPSS for Windows - Fifth edition. Sage Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Fioravanti, G., Bocci Benucci, S., Ceragioli, G., y Casale, S. (2022). How the exposure to beauty ideals on social networking sites influences body image: A systematic review of experimental studies. Adolescent Research Review, 7(3), 419-458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00179-4 [ Links ]

Garner, D. M. (1991). Eating Disorder Inventory - 2. Psychological Assessment Resources. [ Links ]

Gerson, J., Plagnol, A. C., y Corr, P. J. (2017). Passive and active Facebook use measure (PAUM): Validation and relationship to the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 81-90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.034 [ Links ]

Góngora, V. C., Cruz Licea, V., Mebarak Chams, M. R., y Thornborrow, T. (2020). Assessing the measurement invariance of a Latin-American Spanish translation of the Body Appreciation Scale-2 in Mexican, Argentinean, and Colombian adolescents. Body Image, 32, 180-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.01.004 [ Links ]

Grippo, K. P., y Hill, M. S. (2008). Self-objectification, habitual body monitoring, and body dissatisfaction in older European American women: Exploring age and feminism as moderators. Body Image, 5(2), 173-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.11.003 [ Links ]

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [ Links ]

Holland, G., y Tiggemann, M. (2016). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008 [ Links ]

Jankauskiene, R., y Baceviciene, M. (2022). Media pressures, internalization of appearance ideals and disordered eating among adolescent girls and boys: Testing the moderating role of body appreciation. Nutrients, 14(11), 2227. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14112227 [ Links ]

Jarman, H. K., Marques, M. D., McLean, S. A., Slater, A., y Paxton, S. J. (2021a). Motivations for social media use: Associations with social media engagement and body satisfaction and well-being among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(12), 2279-2293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01390-z [ Links ]

Jarman, H. K., Marques, M. D., McLean, S. A., Slater, A., y Paxton, S. J. (2021b). Social media, body satisfaction and well-being among adolescents: A mediation model of appearance-ideal internalization and comparison. Body Image, 36, 139-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.11.005 [ Links ]

Karazsia, B. T., y Berlin, K. S. (2018). Can a mediator moderate? Considering the role of time and change in the mediator-moderator distinction. Behavior Therapy, 49(1), 12-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.10.001 [ Links ]

McArthur, L., Holbert, D., y Pena, M. (2005). An exploration of the attitudinal and perceptual dimensions of body image among male and female adolescents from six Latin American cities. Adolescence, 40, 801-816. [ Links ]

Meehan, O. L., y Katzman, M. A. (2001). Argentina: The social body at risk. En M. Nasser, M. A. Katzman y R. Gordon (Eds.), Eating disorders and cultures in transition (pp. 148-162). Routledge. [ Links ]

Modica, C. (2019). Facebook, body esteem, and body surveillance in adult women: The moderating role of self-compassion and appearance-contingent self-worth. Body Image, 29, 17-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.02.002 [ Links ]

Murawski, B., Elizathe, L., Custodio, J., y Rutsztein, G. (2015). Validación argentina del Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3. Revista Mexicana de Trastornos Alimentarios, 6(2), 73-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmta.2015.09.001 [ Links ]

Paxton, S. J., McLean, S. A., y Rodgers, R. F. (2022). “My critical filter buffers your app filter”: Social media literacy as a protective factor for body image. Body Image, 40, 158-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.009 [ Links ]

Quittkat, H. L., Hartmann, A. S., Düsing, R., Buhlmann, U., y Vocks, S. (2019). Body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance, and body appreciation in men and women over the lifespan. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 864. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00864 [ Links ]

Ridgway, J. L., y Clayton, R. B. (2016). Instagram unfiltered: exploring associations of body image satisfaction, Instagram #selfie posting, and negative romantic relationship outcomes. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(1), 2-7. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0433 [ Links ]

Roberts, S. R., Maheux, A. J., Hunt, R. A., Ladd, B. A., y Choukas-Bradley, S. (2022). Incorporating social media and muscular ideal internalization into the tripartite influence model of body image: Towards a modern understanding of adolescent girls’ body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 41, 239-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.03.002 [ Links ]

Rodgers, R. F., y Melioli, T. (2016). The relationship between body image concerns, eating disorders and internet use, Part I: A review of empirical support. Adolescent Research Review , 1(2), 95-119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-015-0016-6 [ Links ]

Rodgers, R. F., Paxton, S. J., y Wertheim, E. H. (2021). #Take idealized bodies out of the picture: A scoping review of social media content aiming to protect and promote positive body image. Body Image, 38, 10-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.03.009 [ Links ]

Rodgers, R. F., y Rousseau, A. (2022). Social media and body image: Modulating effects of social identities and user characteristics. Body Image, 41, 284-291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.02.009 [ Links ]

Rodgers, R. F., Wertheim, E. H., Paxton, S. J., Tylka, T. L., y Harriger, J. A. (2022). #Bopo: Enhancing body image through body positive social media - evidence to date and research directions. Body Image, 41, 367-374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.03.008 [ Links ]

Saiphoo, A. N., y Vahedi, Z. (2019). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 259-275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.028 [ Links ]

Strubel, J., Petrie, T. A., y Pookulangara, S. (2018). “Like” me: Shopping, self-display, body image, and social networking sites. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 7(3), 328-344. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000133 [ Links ]

International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2022). ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures - 2021. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. [ Links ]

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., y Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Thompson, J. K., van den Berg, P., Roehrig, M., Guarda, A. S., y Heinberg, L. J. (2004). The sociocultural attitudes towards appearance scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35(3), 293-304. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10257 [ Links ]

Tiggemann, M., Hayden, S., Brown, Z., y Veldhuis, J. (2018). The effect of Instagram “likes” on women’s social comparison and body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 26, 90-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.07.002 [ Links ]

Tylka, T. L., Rodgers, R. F., Calogero, R. M., Thompson, J. K., y Harriger, J. A. (2023). Integrating social media variables as predictors, mediators, and moderators within body image frameworks: Potential mechanisms of action to consider in future research. Body Image, 44, 197-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.01.004 [ Links ]

Tylka, T. L., y Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015a). The Body Appreciation Scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image, 12, 53-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.09.006 [ Links ]

Tylka, T. L., y Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015b). What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image, 14, 118-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.001 [ Links ]

Veldhuis, J., Alleva, J. M., Bij de Vaate, A. J., Keijer, M., y Konijn, E. A. (2020). Me, my selfie, and I: The relations between selfie behaviors, body image, self-objectification, and self-esteem in young women. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 9(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000206 [ Links ]

Wagner, C. N., Aguirre Alfaro, E., y Bryant, E. M. (2016). The relationship between Instagram selfies and body image in young adult women. First Monday, 21(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v21i9.6390 [ Links ]

Wang, S. B., Haynos, A. F., Wall, M. M., Chen, C., Eisenberg, M. E., y Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2019). Fifteen-year prevalence, trajectories, and predictors of body dissatisfaction from adolescence to middle adulthood. Clinical Psychology Science, 7(6), 1403-1415. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619859331 [ Links ]

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Liu, H., Xie, X., Wang, P., y Lei, L. (2020). Selfie posting and self-esteem among young adult women: A mediation model of positive feedback and body satisfaction. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(2), 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318787624 [ Links ]

Received: March 04, 2023; Revised: June 04, 2023; Accepted: June 22, 2023

texto en

texto en